T and Field Events Information Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kstatenotes052213 KSU Track Notes

- Erik Kynard - 2012 Olympic Silver Medalist Back-to-Back NCAA Champion 9 NCAA Champions since 2000 Back-to-Back Women’s Big 12 Champions 2001 • 2002 INDOOR WEEK 10: NCAA WEST PRELIMINARY ROUNDS May 23-25 DECEMBER Location: Austin, Texas 7 CAROL ROBINSON WINTER PENTATHLON ______DICK: 1ST Stadium: Mike A. Myers Stadium 8 KSU ALL-COMERS ______________11: 1ST PLACE Twitter: @kstate_gameday @ncaa ____________GIBBS/WILLIAMS: SCHOOL RECORDS Hashtags: #KStateTF #NCAATF JANUARY Live Results: texassports.com/livestats/c-track/ Live Video: texassports.com 11 JAYHAWK CHALLENGE ________________8: 1ST PLACE Tickets: All-Session: $25 adult, $15 (youth, senior); Single-Day: $10/7 19 WILDCAT INVITATIONAL ____________18: 1ST PLACE 24-26 BILL BERGAN INVITATIONAL ______MEN, WOMEN: 3RD PLACE WILDCATS BEGIN POSTSEASON QUEST IN AUSTIN FEBRUARY This week marks the beginning of the postseason for the Kansas State track and field team as a 1-2 SEVIGNE HUSKER INVITATIONAL __________1: 1ST PLACE group of Wildcats are headed to Austin, Texas, for the NCAA West Preliminary Rounds. The top 8 DON KIRBY COLLEGIATE INVITATIONAL RODRIGUEZ: SCHOOL RECORD 48 individuals and top 24 relays in the region will compete over three days of action from Mike 8-9 IOWA STATE CLASSIC ______________________ A. Myers Stadium with 12 spots on the line to advance to the NCAA Championship next 15 NEBRASKA TUNE-UP________________LINCOLN, NEB. month. 16 KSU OPEN __________________18: 1ST PLACE ________KYNARD: SCHOOL RECORD, AHEARN RECORD K-State has nine individuals set to compete for the men along with both the 4x100 and 4x400 relays. The women’s team has 12 individuals in a total of 14 entries, plus both relays. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

PrimeTime Timing - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:20 PM 2/27/2021 Page 1 2021 Big 12 Championships - 2/26/2021 to 2/27/2021 Hosted by Texas Tech University Sports Performance Center - Lubbock, TX Results Women 60 Meter Dash Women 200 Meter Dash Collegiate: 7.07 C3/10/2018 Aleia Hobbs Collegiate: 22.38 C3/10/2018 Gabby Thomas Collegiate: 7.07 C2/11/2017 Hannah Cunliffe Meet: 22.79 M 2016 Courtney Okolo Meet: 7.21 M 2004 Sanya Richards Meet: 22.79 M 2/26/2021 Kynnedy Flannel Facility: 7.13 F2/12/2021 Twanisha Terry Facility: 22.79 F2/26/2021 Kynnedy Flannel NameYr School Prelims NameYr School Prelims Preliminaries Preliminaries 1Kynnedy Flannel JR Texas 7.23Q 1Kynnedy Flannel JR Texas M 22.79q 2Kevona Davis FR Texas 7.31Q 2Kevona Davis FR Texas 23.20q 3Wurrie Njadoe SR Kansas State 7.46Q 3Arria Minor SO Baylor 23.24q 4Sydney Washington SR Baylor 7.46Q 4Mariah Ayers SO Baylor 23.56q 5Monae' Nichols SR Texas Tech 7.43q 5Wurrie Njadoe SR Kansas State 23.61q 6Peyton Ricks JR Texas Tech 7.48q 6Peyton Ricks JR Texas Tech 23.71q 7Caira Pettway SR Baylor 7.50q 7Honour Finley SR Kansas 23.80q 8Demitra Carter SR Baylor 7.51q 8Emelia Chatfield FR Texas 23.95q 9Gabrielle McDonald SR Texas Tech 7.52 9Christina Ollison SR Oklahoma Sta 24.11 10Hope Glenn SR TCU 7.52 10Ja'Leesa Giles SR Oklahoma 24.15 11Sophia Falco SR Texas 7.53 11Demitra Carter SR Baylor 24.19 12Kennedy Blackmon JR Oklahoma 7.53 12Sydney Washington SR Baylor 24.20 13Ja'Leesa Giles SR Oklahoma 7.56 13Brooke Givens SO Oklahoma Sta 24.31 14Chanel Brissett SR Texas 7.56 14Ahmya -

C.F.P.I. Timing & Data

C.F.P.I. Timing & Data - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER Page 1 Ohio Valley Conference Indoor Championship 2019 - 2/20/2019 to 2/21/2019 Results at www.cfpitiming.com Birmingham Complex in Birmingham, AL Meet Program Event 1 Women 60 Meter Dash (29) Event 5 Women 200 Meter Dash (31) 8 Advance: Top 1 Each Heat plus Next 4 Best Times Top 8 Advance by Time Wednesday 2/20/2019 - 5:45 PM Wednesday 2/20/2019 - 7:00 PM World: 6.92 2/11/1993 Irina Privalova World: 21.87 2/13/1993 Merlene Ottey American: 6.95 3/12/1993 Gail Devers American: 22.33 3/2/1996 Gwen Torrence Collegiate: 7.09 3/11/2001 Williams/ Brooks Collegiate: 22.38 3/10/2018 Gabby Thomas Facility: 7.07 3/3/2012 Gloria Asumu Facility: 22.47 3/12/2016 Felicia Brown Conference: 7.42 2015 Ayonna Cartwright Conference: 23.54 1996 Nidia Graham Lane Name Yr School Seed Time Lane Name Yr School Seed Time Heat 1 of 4 Prelims Heat 1 of 8 Prelims 2 16 Johnson, Tiyanna FR Austin Peay 7.79 3 70 Coleman, Vivica FR E. Illinois 26.47 3 198 Hagans, Rachel FR Murray St. 7.73 4 346 Roberts, Khemani SR TN Tech 24.90 4 361 Pilcher, Jasmyn JR TN - Martin 8.24 5 68 Atchison, Morgan SO E. Illinois NT 5 308 Jimmar, Kyla JR TN State 7.99 6 242 Tomlinson, Georgia SR SE Missouri 25.73 6 215 White, Daijah SR Murray St. -

Media Kit Contents

2005 IAAF World Outdoor Track & Field Championship in Athletics August 6-14, 2005, Helsinki, Finland Saturday, August 06, 2005 Monday, August 08, 2005 Morning session Afternoon session Time Event Round Time Event Round Status 10:05 W Triple Jump QUALIFICATION 18:40 M Hammer FINAL 10:10 W 100m Hurdles HEPTATHLON 18:50 W 100m SEMI-FINAL 10:15 M Shot Put QUALIFICATION 19:10 W High Jump FINAL 10:45 M 100m HEATS 19:20 M 10,000m FINAL 11:15 M Hammer QUALIFICATION A 20:05 M 1500m SEMI-FINAL 11:20 W High Jump HEPTATHLON 20:35 W 3000m Steeplechase FINAL 12:05 W 3000m Steeplechase HEATS 21:00 W 400m SEMI-FINAL 12:45 W 800m HEATS 21:35 W 100m FINAL 12:45 M Hammer QUALIFICATION B Tuesday, August 09, 2005 13:35 M 400m Hurdles HEATS Morning session 13:55 W Shot Put HEPTATHLON 11:35 M 100m DECATHLON\ Afternoon session 11:45 M Javelin QUALIFICATION A 18:35 M Discus QUALIFICATION A 12:10 M Pole Vault QUALIFICATION 18:40 M 20km Race Walking FINAL 12:20 M 200m HEATS 18:45 M 100m QUARTER-FINAL 12:40 M Long Jump DECATHLON 19:25 W 200m HEPTATHLON 13:20 M Javelin QUALIFICATION B 19:30 W High Jump QUALIFICATION 13:40 M 400m HEATS 20:05 M Discus QUALIFICATION B Afternoon session 20:30 M 1500m HEATS 14:15 W Long Jump QUALIFICATION 20:55 M Shot Put FINAL 14:25 M Shot Put DECATHLON 21:15 W 10,000m FINAL 17:30 M High Jump DECATHLON 18:35 W Discus FINAL Sunday, August 07, 2005 18:40 W 100m Hurdles HEATS Morning session 19:25 M 200m QUARTER-FINAL 11:35 W 20km Race Walking FINAL 20:00 M 3000m Steeplechase FINAL 11:45 W Discus QUALIFICATION 20:15 M Triple Jump QUALIFICATION -

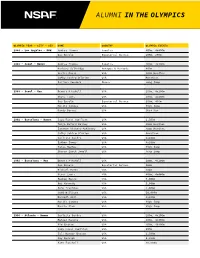

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

NCAA Women: Duncan Powers LSU —

Volume 11, No. 42 June 12, 2012 version ii — NCAA Women: Duncan Powers LSU — by David Woods LSU scored 76 points to Oregon’s 62. In egon also thrived in that area—scoring 30— Des Moines, Iowa, June 6–9—For LSU, eight of the 14 previous editions, 62 would but balance couldn’t surmount LSU speed. it was like most years: an NCAA women’s have been enough, and it is the most the Moreover, Oregon soph English Gardner team title; for Oregon, it was like the previ- Ducks have ever scored. beat Duncan in the 100. Gardner’s time— ous three: Wait another year. Three-time defending champ Texas A&M against a 1.7 wind—was 11.10. That equates Led by rising superstar Kimberlyn Dun- was 3rd (38), and Kansas and Clemson shared to 10.98 with no wind. Duncan’s speed was the key to the Tiger team win MIKE SCOTT can, the Tigers exceeded projections to annex 4th with 28. Gardner also surprisingly led off the 4x4, their 15th title in 26 years. “You always think you could have done and Oregon chopped four seconds off the The Ducks, who have won the past three a little better here or done something a little school record to post the No. 2 time in colle- indoor titles, finished with a flourish, setting differently there, but in the end, 62 points— giate history. LSU, at 3:24.59, became No. 3. a meet record of 3:24.54 in the 4x4, but were the women had a pretty good meet,” Oregon After lowering her world 200 lead to a 2nd, as they were in ’09, ’10 and ’11. -

RESULTS 60 Metres Men - Final

Sopot (POL) World Indoor Championships 7-9 March 2014 RESULTS 60 Metres Men - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Indoor Record WIR 6.39 Maurice GREENE USA 24 Madrid 3 Feb 1998 World Indoor Record WIR 6.39 Maurice GREENE USA 27 Atlanta, GA 3 Mar 2001 Championship Record CR 6.42 Maurice GREENE USA 25 Maebashi 7 Mar 1999 World Leading WL 6.47 James DASAOLU GBR 27 Birmingham (NIA), GBR 15 Feb 2014 Area Indoor Record AIR National Indoor Record NIR Personal Best PB Season Best SB Final 8 March 2014 20:56 START TIME PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 202 Richard KILTY GBR 02 Sep 89 3 6.49 PB 0.120 2 387 Marvin BRACY USA 15 Dec 93 6 6.51 0.138 3 330 Femi OGUNODE QAT 15 May 91 5 6.52 0.160 4 139 Bingtian SU CHN 29 Aug 89 1 6.52 NIR 0.147 5 416 Gerald PHIRI ZAM 06 Oct 88 7 6.52 NIR 0.141 6 192 Dwain CHAMBERS GBR 05 Apr 78 2 6.53 0.139 7 245 Nesta CARTER JAM 11 Oct 85 4 6.57 0.129 8 255 Kimmari ROACH JAM 21 Sep 90 8 6.58 0.159 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 6.39 Maurice GREENE (USA) Madrid 3 Feb 98 6.47 James DASAOLU (GBR) Birmingham (NIA), GBR 15 Feb 14 6.41 Andre CASON (USA) Madrid 14 Feb 92 6.48 Jimmy VICAUT (FRA) Birmingham (NIA), GBR 15 Feb 14 6.42 Dwain CHAMBERS (GBR) Torino 7 Mar 09 6.48 Marvin BRACY (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 6.43 Tim HARDEN (USA) Maebashi 7 Mar 99 6.49 Yunier PÉREZ (CUB) Moskva (CSKA) 2 Feb 14 6.45 Bruny SURIN (CAN) Liévin 13 Feb 93 6.49 Trell KIMMONS (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 6.45 Leonard MYLES-MILLS (GHA) Colorado Springs, -

University of Texas at Austin Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:20 PM 3/26/2021 Page 1 93Rd Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.Of Texas-Mike A

University of Texas at Austin Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:20 PM 3/26/2021 Page 1 93rd Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.of Texas-Mike A. Myers Stadium-Austin,TX - 3/25/2021 to 3/27/2021 Results - Friday 5 #12942 Marco Arevalo JR TAMU-Kingsvlle 16.40m Event 69 Women Shot Put Section B Univ/Coll 6 #12952 Jorge Rios JR TAMU-Kingsvlle 16.32m World: 22.63m W 1987 Natalya Lisovskaya 7 #12904 Kevin Steward SR S.F. Austin 16.07m American: 20.63m A 2016 Michelle Carter 8 #12626 Chris Samaniego JR North Texas 15.90m Collegiate: 19.46m C 2018 Maggie Ewen 9 #13181 Brandon Busby TX State 15.89m Myers Std: 18.96m F 2013 Tia Brooks 10 #13524 Tyler Pickens SR West TX A&M 15.67m TX Relays: 18.58m M 2006 Laura Gerraughty 11 #13432 Jorge Ayala JR UTSA 15.37m Name Yr School Finals 12 #13097 Sean Stavinoha FR Texas 14.90m Finals 13 #12930 Steven Sanchez SR TAMU-Commerce 14.82m 1 #12515 Alanna Arvie SR McNeese St. 15.72m --- #13224 Braden Darrow SR TX Tech FOUL 2 #12333 Nu'uausala Tuilefano SO Houston 15.66m 3 #12435 Naomi Mojica JR Liberty 15.44m Event 55 Women Pole Vault Univ/Coll 4 #12152 Ebonie Whitted SO Bowling Green 15.19m World: 5.06m W 2009 Yelena Isinbaeva 5 #13042 Kiana Lowery FR Texas 15.12m American: 5.00m A 2016 Sandi Morris 6 #12462 Amber Hart JR LSU 15.08m Collegiate: 4.73m C 2019 Olivia Gruver 7 #12612 Jaleisa Shaffer SR North Texas 14.92m Myers Std: 4.91m F 2019 Jenn Suhr 8 #12836 Josey Starner SO South Dakota 14.74m TX Relays: 4.60m M 2018 Lisa Gunnarsson 9 #12543 Emily Offenheiser SO Missouri 14.40m Name Yr School Finals 10 #12432 Chelsea -

Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 9:47 PM 3/14/2014 Page 1 NCAA Division 1 2014 Indoor Championship Albuquerque Convention Center -U

RecordTiming.com - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 9:47 PM 3/14/2014 Page 1 NCAA Division 1 2014 Indoor Championship Albuquerque Convention Center -U. New Mexico Albuquerque NM - 3/14/2014 to 3/15/2014 Meet Program - Saturday Event 34 Indoor Pentathlon: #1 Women 60 Meter Hurdles Event 34 Indoor Pentathlon: #2 Women High Jump Four grouped sections. Alternate lanes for hurdles. Two grouped pits. No five-alive. Lanes 1,3,5,7 Start height determined by Referee. Lane Name Yr School Seed Time Pos Name Yr School Seed Mark Section 1 of 4 Finals Flight 1 of 2 Finals 1 101 Kendell Williams FR Georgia NT 1 207 Brittney Howell SR Penn State NH 2 2 290 Chari Hawkins JR Utah State NH 3 115 Erica Twiss JR Kansas State NT 3 264 Jena Hemann JR Texas A&M NH 4 4 137 Thea LaFond JR Maryland NH 5 218 Allison Reaser SR San Diego St NT 5 225 Sarah Graham SO South Caroli NH 6 6 18 Alex Gochenour SO Arkansas NH 7 306 Deanna Latham JR Wisconsin NT 7 101 Kendell Williams FR Georgia NH 8 8 160 Erica Bougard JR Miss State NH Section 2 of 4 Finals Flight 2 of 2 Finals 1 99 Lucie Ondraschkova SR Georgia NT 1 159 Jess Herauf SO Minnesota NH 2 2 115 Erica Twiss JR Kansas State NH 3 18 Alex Gochenour SO Arkansas NT 3 218 Allison Reaser SR San Diego St NH 4 4 62 Sarah Chauchard SR Eastern Mich NH 5 94 Quintunya Chapman JR Georgia NT 5 99 Lucie Ondraschkova SR Georgia NH 6 6 70 Brittany Harrell JR Florida NH 7 225 Sarah Graham SO South Caroli NT 7 94 Quintunya Chapman JR Georgia NH 8 8 306 Deanna Latham JR Wisconsin NH Section 3 of 4 Finals Event 34 Indoor Pentathlon: #3 Women Shot Put 1 62 Sarah Chauchard SR Eastern Mich NT 2 Two grouped sections. -

Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 9:16 PM 2/1/2013 Page 1

Track Timing and Data Management - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 9:16 PM 2/1/2013 Page 1 New Mexico Collegiate Classic Results Event 3 Women 200 Meter Dash ================================================================ Non-Collegt: A 23.24 2/4/2011 Charonda Willimas, Nike Collegiate: T 23.20 2/26/2011 Jessica Young, TCU Name Year School Finals ================================================================ Section 1 1 Alishia Perkins New Mexico St. 24.17 2 Germe Poston Arizona 24.40 3 Yolanda Suggs Utep 24.50 4 Jokira Jiles Miami 24.52 5 Magen Del Pino Utep 24.98 Section 2 1 Jenna Banegas New Mexico St. 24.56 2 Salima Jamali Western State 25.33 3 Azia Walker Arizona 26.18 26.171 4 Chelsea Fenderson Adams State 26.29 Section 3 1 Maderia Toatley San Diego St. 24.80 2 Kendra Walker New Mexico St. 24.99 3 Morgan Malone Air Force 25.80 4 Sunayna Wahi Adams State 26.34 5 Elyse Houston Miami 26.87 Section 4 1 Sarah Snider West Texas A&M 25.46 2 April Panteau Run With US 25.50 3 Haley Sanner New Mexico 25.60 4 Whitney Rowe Colorado Mesa 25.81 5 Deandra Nelson New Mex High 26.62 Section 5 1 Cherish Morrison New Mexico St. 25.67 2 Paula Bowens West Texas A&M 25.99 3 Dearra McNeal Langston 26.00 4 Naomi Alston Air Force 26.64 5 Sheneika Rochester New Mex High 27.75 Section 6 1 Libby Strickland West Texas A&M 25.75 2 Tara Tarrant West Texas A&M 26.18 26.176 3 Darion Johnson Langston 26.42 4 Christina Clark New Mexico 27.44 5 Emerald Damge Western State 27.61 Section 7 1 Nicole Oudenaarden San Diego St. -

2016TN02 Mlist

Volume 15, No. 02 January 06, 2016 version i — 2015 U.S. Men’s Lists — KEY TO LISTS compiled by Glen McMicken These lists give the top 40 U.S. performers (and top 10 per- formances, denoted by a ——) of the 2015 season, with an appending of those foreign collegians whose marks fall into 100 METERS that range. In the wind-aided category, the domestics and 9.74 ............ Justin Gatlin (Nike) .................. 5/15 ............. Doha DL foreign collegians are commingled (' after name = foreigner 9.75 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 6/04 ............ Rome DL on windy list). Relay teams may contain non-U.S. nationals. ................... ——Gatlin ................................ 7/09 ...... Lausanne DL 9.77 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 8/23 ............ World Ch Athletes who change nationality during the season are listed 9.78 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 7/17 .........Monaco DL with their nationality as of the date of the mark, so marks 9.80 ............ ——Gatlin ................................ 8/23 ............ World Ch here may not be their actual best of the year. 9.84 ............ **Trayvon Bromell (Bay) ........... 6/25 ................ USATF Open athletes and high schoolers have no notation before 9.86 ............ Mike Rodgers (Nike) ................ 8/23 ............ World Ch their name. Collegians are noted by class: - = senior; * = 9.87 ............ Tyson Gay (Nike) ..................... 6/26 ................ USATF junior; **=soph; *** = frosh. 9.88 ............ ——Gay................................... 5/30 ..........Eugene DL (A) = altitude over 1000m (in affected events only). Wind-aided ................... ——Rodgers ........................... 7/11 ........ Madrid IWC marks are those of greater than 2.0mps. Windy marks are **11 performances by 4 performers** listed only if superior to the best legal mark (windy perfor- 9.93 ............ Ryan Bailey (Nike) ................... 5/09 ..... Kingston IWC mances listed to level of legal performances). -

Tyson Invitational Top Ten List

TYSON INVITATIONAL TOP TEN LIST (MEN’S EVENTS) 60 METERS 3000 METERS HIGH JUMP HEPTATHLON 6.46 Terrence Trammell, USA, 2003 7:35.65 Boaz Cheboiywo, Kenya, 2006 2.33m Andra Manson, Texas, 2007 5,826 Terry Prentice, Unattached, 2013 6.48 John Capel, USA, 2003 7:38.30 Boaz Cheboiywo, NIKE, 2004 2.33m Veron Turner, Oklahoma, 2018 5,277 Denim Rogers, Houston Baptist, 2019 6.50 Maurice Greene, USA, 2003 7:38.59 Alistair Cragg, Arkansas, 2004 2.33m Erik Kynard, Kansas State, 2011 4,907 Lane Austell, Unattached, 2013 6.52 Lerone Clarke, Jamaica, 2012 7:40.17 Daniel Lincoln, NIKE, 2004 2.30m Jacorian Duffield, NIKE, 2017 4,276 Daniel Spejcher, Unattached, 2019 6.52 John Teeters, OK State, 2015 (Prelims) 7:40.17 Kevin Sullivan, Reebok, 2007 2.30m Donald Thomas, Auburn, 2007 4,019 Hootie Hurley, Unattached, 2019 6.53 Jon Drummond, Nike, 2000 7:40.25 Matt Tegenkamp, NIKE, 2007 2.29m Bradley Adkins, Texas Tech, 2016 3,789 Kyle Costner, Unattached, 2019 6.54 John Teeters, OK State, 2015 (Semis) 7:40.53 Alistair Cragg, Adidas, 2005 2.28m JuVaughn Harrison, LSU, 2020 3,011 Julius Sommer, Arkansas, 2013 6.54 Maurice Greene, USA, 2003 (Prelims) 7:40.72 Markos Geneti, Adidas, 2005 2.28m Christoff Bryan, Kansas State, 2015 6.54 Terrence Trammell, USA, 2003 (Prelims) 7:41.59 Adam Goucher, USA, 2006 2.27m Marcus Jackson, Miss State, 2014 6.54 Jason Smoots, NIKE, 2005 7:42.17 Kevin Sullivan, Canada, 2006 2.27m Derek Drouin, Indiana, 2011 HEPTATHLON 60M 6.54 Rakieem Salaam, Oklahoma 2011, (Semis) 2.27m Ricky Robertson, Mississippi, 2011 7.01 Terry Prentice,