NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Res Pers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thompson Rivers University Location and Campus Dr

Cyndi McLeod Associate Vice President, TRU World Chief Executive Officer of Global Operations Thompson Rivers University Location and Campus Dr. Kathleen Scherf President and Vice-Chancellor Thompson Rivers University is located in the city of Kamloops, and the province of British Columbia, In Western Canada Thompson Rivers University ` Dual-Sector, Dual-Mode University ` Founded in 1970, public, degree-granting ` Annual Budget: $138.5 million, Research Budget: $10.6 million ` 10,000 Canadian students + 16,000 distance education students ` More than 1200 International Students from 70 countries ` Approx. 570 faculty, and 465 staff ` 100 different programs at the certificate, diploma, undergraduate and masters level ` 400 distance education courses Thompson Rivers University (International) ` 60 different training projects in more than 30 countries worldwide ` 600 Short Term trainees each year for Professional Programs ` 1400 offshore students studying transnational education programs ` Projects, partnerships in over 30 countries ` 60 bilateral exchange agreements worldwide ` 220 exchange agreements through ISEP Thompson Rivers University ` Began in 1970 as a community college, Cariboo College, to deliver career-technical and two-year academic university transfer programs during the provinces’ initial expansion of post-secondary education. It evolved into The University College of the Cariboo, and has recently received full university status with a change in name to Thompson Rivers University, and is designated as a special purpose university. -

Stereotypes of Age Differences in Personality Traits: Universal and Accurate?

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology © 2012 American Psychological Association 2012, Vol. ●●, No. ●, 000–000 0022-3514/12/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0029712 Stereotypes of Age Differences in Personality Traits: Universal and Accurate? Wayne Chan Robert R. McCrae National Institute on Aging Baltimore, Maryland Filip De Fruyt Lee Jussim Ghent University Rutgers University Corinna E. Löckenhoff Marleen De Bolle Cornell University Ghent University Paul T. Costa Jr. and Angelina R. Sutin Anu Realo National Institute on Aging University of Tartu Ju¨ri Allik Katsuharu Nakazato University of Tartu and the Estonian Academy of Sciences Iwate Prefectural University Yoshiko Shimonaka Martina Hrˇebı´cˇkova´ and Sylvie Graf Bunkyo Gakuin University Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Michelle Yik Marina Brunner-Sciarra Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Cayetano Heredia University Nora Leibovich de Figueora and Vanina Schmidt Chang-kyu Ahn University of Buenos Aires Pusan National University Hyun-nie Ahn Maria E. Aguilar-Vafaie Ewha Womans University Tarbiat Modares University Jerzy Siuta and Barbara Szmigielska Thomas R. Cain Jagiellonian University Hampshire College Jarret T. Crawford Khairul Anwar Mastor The College of New Jersey Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Jean-Pierre Rolland Florence Nansubuga Universite´ Paris Ouest Nanterre La De´fense Makerere University Daniel R. Miramontez Veronica Benet-Martı´nez San Diego Community College District Pompeu Fabra University Je´roˆme Rossier Denis Bratko University of Lausanne University of Zagreb Iris Marušic´ Jamin Halberstadt and Mami Yamaguchi Institute for Social Research in Zagreb University of Otago 1 2 CHAN ET AL. Goran Kneževic´ Thomas A. Martin Belgrade University Susquehanna University Mirona Gheorghiu Peter B. -

JAIR Annual Convention 2015 Program

The 2015Annual Convention of the Japanese Association of International Relations (JAIR) 30th October - 1st November Sendai International Center Aobayama Consortium 〒980-0856 Aobayama, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-0856 Tel. +81-22-265-2211Fax. +81-22-265-2485E-mail. [email protected] October 30 (Friday) Registration: 12:00 Afternoon Sessions: 13:00-15:30 Session 1. International Organizations and International Order: the 1940s Reconsidered Chair OSHIBA Ryo (Aoyama Gakuin University) Speakers HOSOYA Yuichi (Keio University) “Between Universalism and Regionalism: Britain and the Creation of the United Nations” MIMAKI Seiko (Kansai Gaidai University) “American Ideals for an International Organization” ISHIGURO Ai (Osaka University of Commerce) “Republic of China and the United Nations" Discussants YAMADA Tetsuya (Nanzan University) HANZAWA Asahiko (Meiji Gakuin University) Session 2. Rescuing Classical Theories of International Relations from the ‘English School’ Chair OGAWA Hiroyuki (The University of Tokyo) Speakers NISHIMURA Kuniyuki (Hokkaido University of Education) "Never Face ‘an American Social Science’: A Failure of the English School IR” KUZUYA Aya (Meiji Gakuin University) " H.Butterfield and Masataka Kôsaka: Reconsidering Classical Theories of International Relations from the Perspective of German Intellectual Tradition" MIYASHITA Yutaka (No Affiliation) “Self-Righteousness of Defending the Status Quo: On Herbert Butterfield’s Political Judgement" Discussants ONAKA Makoto (J. F. Oberlin University) MIYASHITA Yuichiro (Matsuyama University) -

The Pros and Cons of Hosting

TRU Homestay Program Host Family Guide What is the Homestay Program? ................................................................................................ 4 Who are the Students? ..................................................................................................................... 4 Programs .............................................................................................................................................. 4 The Pros and Cons of Hosting ...................................................................................................... 5 Benefits ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Potential challenges ......................................................................................................................... 5 Finances and Obligations ................................................................................................................ 7 Rent / Fees .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Family Vacations ............................................................................................................................... 7 Student Vacations ............................................................................................................................ 8 Restaurants ........................................................................................................................................ -

Outline of the Student Exchange System in Japan

2007 Student Services Division, Higher Education Bureau Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (MEXT) NK181.812/ .6,1,03ݘ0..5C,glbb The Objectives of Student Exchange ………………………………………………3 Ⅰ Development of International Student Exchange Policies 1. Development of new international student exchange policies ………………………4 2. Acceptance of international students in major countries ……………………………4 3. Development of new policies for international student exchanges (An outline of the report submitted by the Central Council for Education) ……………5 4. Establishment of the Japan Student Services Organization …………………………6 Ⅱ Acceptance of International students in Japan 1. Trends in the number of international students in Japan ……………………………7 2. Number of international students by region of origin ………………………………8 3. Number of international students by country/region of origin ………………………8 4. Number of international students by type of educational institution …………………9 5. Number of international students by educational institution and sector ……………10 6. Number of international students by region and prefecture …………………………10 7. Number of international students by field of study …………………………………11 8. Number of international students by university ……………………………………11 Ⅲ Measures for the Acceptance of International Students 1. Measures before entering a Japanese university 1. Information and counseling services on study in Japan …………………………12 2. Procedures for entering Japan and visa application ………………………………12 3. System of Japanese language education …………………………………………13 • System of Japanese language education ………………………………………13 • Measures regarding students enrolled at Japanese language schools ………13 • Preparatory Japanese language courses offered at private universities and junior colleges ……………………………………15 • Preparatory education for foreign government sponsored students …………16 • Role of university preparatory courses ………………………………………17 4. Recruitment of Japanese government scholarship students ……………………18 5. -

2019 Newsletter

2019 Newsletter WDCAG2019 (UVic) field trip to SṈIDȻEȽ (Gowland Tod Park) led by the SṈIDȻEȽ Resiliency Project's Tiffany Joseph and Sarah Jim (Tsartlip Nation) T-Shirt Stenciling at WDCAG2019 (photos: Ken Josephson) 1 WDCAG Newsletter 2019 Table of Contents WDCAG President’s Message 3 WDCAG Newsletter Editor’s greeting 4 Special Feature: Interviews with: Afia Raja, University of the Fraser Valley 5 Olaf Niemann, University of Victoria 7 News from WDCAG Departments 9 2 WDCAG PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE (submitted by Claire Hay, University of the Fraser Valley) Welcome to the current edition of the WDCAG Newsletter. My name is Claire Hay and I assumed the role of WDCAG President at our last AGM in Victoria in March 2019. The WDCAG and its annual meetings have been a part of my geographic identity since 1996 when I attended my first meeting at UNBC. I was a new MSc student at UAlberta and I was presenting my honours research at my very first conference where I was the last speaker of the day. I was terrified but excited. That experience has stuck with me; the WDCAG provides students of all levels the opportunity to try out the conference-thing, gain experience, receive feedback on their ideas and network with geographers from a myriad of sub-disciplines and fields. The CAG (our national organization) served much the same purpose while promoting the discipline of geography in Canada. I encourage all of you to support the WDCAG and CAG through membership, attendance at regional and national meetings and supporting students in their geographic adventures. -

University of Michigan A0108 B0108

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180108 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659824 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180108 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (UM_NRC_FLAS_GEPA_Section_427_description_2018) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e13 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e14 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e15 Attachment - 1 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_2018_Abstract) e16 9. Project Narrative Form e18 Attachment - 1 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_2018_Narrative) e19 10. Other Narrative Form e69 Attachment - 1 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Table_of_Contents) e70 Attachment - 2 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Appendix_2_Position_Descriptions) e71 Attachment - 3 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Appendix_1_Curriculum_Vitae) e77 Attachment - 4 (NRC_and_FLAS_Applicant_Profile) e145 Attachment - 5 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Diverse_Perspectives) e146 Attachment - 6 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_2018_Acronyms_List) e147 Attachment - 7 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_National_Need) e149 Attachment - 8 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Appendix_5_Letters_of_Support) e150 Attachment - 9 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Appendix_4_Performance_Measures) e156 Attachment - 10 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_Appendix_3_Course_Guide) e161 11. Budget Narrative Form e174 Attachment - 1 (CSAS_NRC_FLAS_2018_Line_Item_Budget) -

TRU: a Globally Minded Campus – a Resource for Academic Departments

TRU: A GLOBALLY MINDED CAMPUS A RESOURCE FOR Academic DEPARTMENTS This resource was created by TRU World in This is seen as a work in progress; a collaborative order to recognize and support all who work and evolving process. The hope is that it to make TRU a globally minded campus that will enrich the dialogue and debate as well as embraces and encourages diversity. motivate individuals to share their experiences and best practices. The Centre for Teaching and Many individuals have contributed to the Learning will play a key role in facilitating this composition of this document by offering ongoing process. their expertise or simply by asking the necessary questions. We invite feedback and contributions to the upcoming edition. This resource was researched and primarily written by Kyra Garson on behalf of TRU World. February, 2007 Her expertise, talents and dedication were recognized by all involved in this project. KAMLOOPS, BC CANADA © 2007 TRU World ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Message from the President and Vice-Chancellor of TRU Thompson Rivers University is committed to fostering global citizenship. We have positioned ourselves as an international university. Global literacy—developing awareness and understanding in order to interact effectively within and among different cultures—has become an increasingly relevant and important educational goal. Cultural diversity is now a significant feature of university campuses in Canada. At TRU, our academic schools and faculties have played a key role in our ongoing success in internationalization. Students from more than 60 countries come to TRU each year to take advantage of our comprehensive range of programs, our unique combinations of flexible learning options, and our balance of theoretical and applied studies. -

The Inaccuracy of National Character Stereotypes

Journal of Research in Personality 47 (2013) 831–842 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Research in Personality journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jrp The inaccuracy of national character stereotypes Robert R. McCrae a, Wayne Chan b, Lee Jussim c, Filip De Fruyt d, Corinna E. Löckenhoff e, Marleen De Bolle d, Paul T. Costa Jr. b, Martina Hrˇebícˇková f, Sylvie Graf f, Anu Realo g, Jüri Allik g,h, Katsuharu Nakazato i, Yoshiko Shimonaka j, Michelle Yik k, Emília Ficková l, Marina Brunner-Sciarra m, Norma Reátigui m, Nora Leibovich de Figueora n, Vanina Schmidt n, Chang-kyu Ahn o, Hyun-nie Ahn p, Maria E. Aguilar-Vafaie q, Jerzy Siuta r, Barbara Szmigielska r, Thomas R. Cain s, Jarret T. Crawford t, Khairul Anwar Mastor u, Jean-Pierre Rolland v, Florence Nansubuga w, Daniel R. Miramontez x, Veronica Benet-Martínez y, Jérôme Rossier z, Denis Bratko aa, Iris Marušic´ ab, Jamin Halberstadt ac, Mami Yamaguchi ac, Goran Knezˇevic´ ad, Danka Puric´ ad, Thomas A. Martin ae, Mirona Gheorghiu af, Peter B. Smith ag, Claudio Barbaranelli ah, Lei Wang ai, Jane Shakespeare-Finch aj, Margarida P. Lima ak, Waldemar Klinkosz al, Andrzej Sekowski al, Lidia Alcalay am, Franco Simonetti am, Tatyana V. Avdeyeva an, ⇑ V.S. Pramila ao, Antonio Terracciano ap,b, a 809 Evesham Avenue, Baltimore, MD, USA b National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, MD, USA c Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA d Department of Developmental, Personality, and Social Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium e Department of -

Curriculum Vitae of Kazunori Nozawa

1 Curriculum Vitae of Kazunori Nozawa Office Address (Japan): College of Information Science and Engineering, Ritsumeikan University, 1-1-1 Nojihigashi, Kusatsu, Shiga 525-8577 Japan Tel: +81-77-561-4816 Fax: +81-77-561-5203 E-mail: [email protected] HP: http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/is/~nozawa/index.html Research Lab HP: http://www.eap.is.ritsumei.ac.jp/nlab/ Education 1992-1998 Withdrawn from Ph. D. candidate at Columbia Pacific University, U.S.A. May 1978 Received M.A. (TESL) from The University of Kansas, U.S.A. March 1974 Received B. Ed. (Pedagogy) from Utsunomiya University, Japan Occupation April 2017-Current Specially Appointed Professor & Professor Emeritus, College of Information Science and Engineering, Ritsumeikan University, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan April 2004-March 2017 Professor, Department of Computer Science, College of Information Science and Engineering, Ritsumeikan University, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan April 2003 –Current Professor, Language and Communication Course, Graduate School of Language Education and Information Science, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan April 1998-March 2004 Professor, Faculty of Economics, Ritsumeikan University, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan April 1990-March 1998 Associate Professor, the Language Center, Toyohashi University of Technology, Toyohashi, Aichi, Japan August 1989-March 1990 Associate Professor, School of Humanities and Social Engineering, Toyohashi University of Technology, Toyohashi, Aichi, Japan 2 May 1985-July 1989 Assistant Professor, School of Humanities and Social Engineering, Toyohashi University of Technology, Toyohashi, Aichi, Japan December 1981-April 1985 Assistant, School of Humanities and Social Engineering, Toyohashi University of Technology, Toyohashi, Aichi, Japan August 1978-November 1981 Instructor (EFL), Nagoya International College (Currently Trident School of Languages), Nagoya, Aichi, Japan August 1977-May 1978 Teaching Assistant (Japanese), School of Oriental Languages and Cultures at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, U.S.A. -

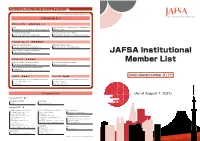

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 317!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of August 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd.