Artificial Hells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Paludians Newsletter March 2006

The Old Paludians Newsletter Founded 1915 Website: www.oldpaludians.org March 2006 Last year we marked our 90th Anniversary with the publication of our new Book called School Ties. This has been well received by everyone and is very much a real part of the social history of Slough. It is available at the Reunion or by post so we can recommend it – it contains many fascinating memories of life at our Schools over the years. Our 2005 Reunion was quite spectacular and a very happy day was rounded off by a rousing rendition of the newly discovered Old Paludians song. Sadly we have lost a number of Old Paludians this past year as the years take their toll. Included in this list are a number of much loved former members of staff. We thank Mrs Lenton for letting us invade the School once again and we also thank the staff who help both in the run-up to the Reunion and on the Day itself. It is an occasion looked forward to by many as a chance to meet up with friends and to exchange news. We hope everyone will enjoy themselves. THE ARCHIVES We received a number of donations of items of School memorabilia to our Archive during the year. Especially noteworthy were a superb set of exercise books from the 1940s given by Joyce Haggerty (Newstead), a mixed collection of rare items (including a Lectern Cover designed and made to celebrate the High School’s 21st birthday) donated by Vivienne Tuddenham and the gift of two photographs both new to us from Audrey Evans. -

W Ycombiensian

THE W YCOMBIENSIAN Sf/r,, 1562 ft VVYCO^ Vol. XI. No. 8 September, 1951 m i i muAHY THE WYCOMBIENSIAN (The Wycombe Royal Grammar School Magazine) E d ito r : A. R. McINTOSH Assisted by M. J. BANHAM EDITORIAL For nine years now this school has ranked as a Public School. It is an honour, to the Headmaster and ourselves, of which we are justly proud, for it is the recognition of great achievements in the first half of this century. But we are also a Grammar School, though a Royal one ; an integral and vital part of the new educa tional system planned in 1944 : and this is no less an honour because it is shared by thousands of other schools. Our relations with the public schools and great grammar schools of the country, in friendly rivalry in sport, candidature for University scholarships, and other things, are much prized. It is perhaps less fashionable to consider our relations with our partners in secondary education, the technical and secondary modern schools, who as Mr. Birley said on Speech Day, have the really exciting future in the next few years. The stock Ministry of Education phrase “ parity of esteem ” is uninspiring. It has not the ring of the true slogan : but it has far more accuracy and justice than most slogans. It does not mean equality, for it is obvious that the grammar school, designed to train managers, teachers, leaders, needs more money, more highly-qualified teachers, more advanced equipment, perhaps more corporate spirit, than the others. It does not mean that being selected for a grammar school at the age of eleven is not a thing to be proud of. -

Dissertation Proposal

EXILE AND EMPIRE: POST-IMPERIAL NARRATIVE AND THE NATIONAL EPIC: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF RUSHDIE’S THE SATANIC VERSES & VIRGIL’S AENEID By KENNETH SAMMOND A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Comparative Literature Written under the direction of Steven F. Walker And approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2011 ©2011 Kenneth Sammond ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Exile and Empire: Post-Imperial Narrative and the National Epic: A Comparative Study of Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and Virgil’s Aeneid By KENNETH SAMMOND Dissertation Director: Professor Steven F. Walker This dissertation juxtaposes Virgil’s Aeneid with Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in order to explore how epics, which question and upend our very ideas of civilization, represent a crisis in culture and anticipate new ways of imagining community. This juxtaposition, developed from allusions to Virgil found in The Satanic Verses, examines how Virgil’s epic imagines empire and how Rushdie’s work, as a type of epic, creates a narrative that I term, ‘post-imperial.’ Post-imperial narrative is defined as part of the evolution of the epic genre and its ways of imagining community. To create this definition, I represent a genealogy of epic traits both structural and thematic, arguing that epic themes express totalizing perspectives and changes that irrevocably alter the world. This genealogy reveals how epics imagine communities by creating self-definitional traits, historical and cosmological contexts, and anticipated futures. -

Cruising Guide for the River Thames

Cruising Guide to The River Thames and Connecting Waterways 2012-2013 Supported by Introduction and Contents As Chairman of BMF Thames Valley, I am immensely Introduction 3 proud to introduce the 2012/13 Cruising Guide to The River Thames Management 4-5 the River Thames and its connecting waterways. The Non-tidal River Thames 7-13 Cruising Guide has been jointly produced with the Environment Agency and is supported by the Port Bridge Heights - Non-tidal River Thames 14 of London Authority - it provides all the relevant St John’s Lock - Shifford Lock 15 information anyone would need whilst boating on Shifford Lock - Sandford Lock 16-17 The River Thames and its connecting waterways. Sandford Lock - Benson Lock 18-19 BMF Thames Valley is a Regional Association of the Cleeve Lock - Sonning Lock 20-21 British Marine Federation, the National trade association for the leisure boating industry. BMF Thames Valley Sonning Lock - Boulter’s Locks 22-23 represents around 200 businesses that all share a Boulter’s Lock - Old Windsor Lock 24-25 passion for our inland waterways. 2012 is going to be Bell Weir Lock - Shepperton Lock 26-27 an exciting year on the River Thames with the London Shepperton Lock - Teddington Lock 28-29 2012 Olympics and the Diamond Jubilee celebrations. What’s new for 2012! The Tidal Thames 30 • New map design Tidal Thames Cruising Times 31 • Complete map of navigable River Thames from Lechlade Teddington Lock - Vauxhall Bridge 32-33 to the Thames Barrier • Information on the non-tidal Thames - Environment Agency Lambeth Bridge -

Mcmillan Book.Indb

Number Seventeen carolyn and ernest fay series in analytical psychology David H. Rosen, General Editor The Carolyn and Ernest Fay edited book series, based initially on the annual Fay Lecture Series in Analytical Psychology, was established to further the ideas of C. G. Jung among students, faculty, therapists, and other citizens and to enhance scholarly activities related to analytical psychology. The Book Series and Lecture Series address topics of im- portance to the individual and to society. Both series were generously endowed by Carolyn Grant Fay, the founding president of the C. G. Jung Educational Center in Houston, Texas. The series are in part a memorial to her late husband, Ernest Bel Fay. Carolyn Fay has planted a Jungian tree carrying both her name and that of her late husband, which will bear fruitful ideas and stimulate creative works from this time forward. Texas A&M University and all those who come in contact with the growing Fay Jungian tree are extremely grateful to Carolyn Grant Fay for what she has done. The holder of the McMillan Professorship in Analytical Psychology at Texas A&M functions as the general editor of the Fay Book Series. A list of titles in this series appears at the end of the book. Finding Jung a special volume Carolyn and Ernest Fay Series in Analytical Psychology Frank N. McMillan Jr., 1952 Finding Jung frank n. mcmillan jr., a life in quest of the lion Frank N. McMillan III Contributions by d avid h . r osen Foreword by Sir l aurens van der Post Texas A&M University Press • College Station Copyright © 2012 by Frank N. -

The London Gazette, 13Th August 1965 7677

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13TH AUGUST 1965 7677 Notice' is hereby given that an application is being Ty Glas Avenue, Llanishen, Cardiff, at all reasonable made to the Yorkshire Ouse & Hull River Authority hours during the period beginning the 13th August by F. R. Christon, of Woodhouse Farm, Husthwaite, 1965 and ending the 10th September 1965. for a licence to abstract the following quantities of 1 Any person who wishes to make representations •water" from the Kyle and tributary in field No. about the application should do so in writing to the 63 O.S. CXX1.3. at the following points of abstrac- Clerk of the South West Wales River Authority at tion: Penyfai House, Penyfai Lane, Llanelly, Carmarthen- Ref point: shire, before the end of the said period. 1 23,000 gallons/hour R. /. Piggott, Divisional Chief Surveyor and 2 23,000 gallons/hour Minerals Manager, on behalf of the National 3 23,000 gallons/hour 4 23,000 gallons/hour Coal Board. the aggregate not to exceed 23,000 gallons /hour. Dated 8th August 1965. A copy of the application and of any map, plan or (261) other document submitted with it may be inspected free of charge at the above address at all reasonable hours during the period 28 days being from 14th August to llth September 1965. Notice is hereby given that applications are being Any person wishing to make representations about made to the Essex River Authority by Brairitree Rural the application should do so in writing to the Clerk District Council for licences to abstract the following of the above authority before the end of the said quantities of water from underground strata (chalk at period. -

[Insert Your Title Here]

Popular Music and the Myth of Englishness in British Poetry by Brian Allen East A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama May 9, 2011 Keywords: Englishness, popular music, British poetry, poetics, national identity Copyright 2011 by Brian Allen East Approved by Jeremy Downes, Chair, Professor of English Jonathan Bolton, Professor of English Virginia M. Kouidis, Associate Professor Ruth C. Crocker, Professor of History Abstract This dissertation deconstructs the myth of Englishness through a comparative analysis of intersections between popular music and the poetry of the British Isles. In particular, my project explores intersections where popular music and poetry critics attempt to define Englishness, intersections where poetry and music combine to perform Englishness, and intersections where poetry and music combine to resist Englishness. In the wake of centuries of colonialism, British cultural expressions comprise a hybrid discourse that reflects global influences. I argue that attempts by critics to preserve the myth of Englishness result in the exclusion of a diversity of voices. Such exclusionary tactics potentially promote the alienation of future readers from British poetry. A comparative analysis of intersections between poetry and popular music expands the current critical discourse on British poetry to incorporate the hybridity of British popular music. Although for comparative purposes I consider music as a literature, I do not focus on song lyrics as the exclusive, or primary “text” of popular music. Instead, I am much more interested in the social forces that transform popular music into an expression of Englishness. -

Reasons to Love Florida: a COUNTY

• ALACHUA • BAKER • BAY • BRADFORD • BREVARD • BROWARD • CALHOUN • CHARLOTTE • CITRUS • CLAY • COLLIER • COLUMBIA • DESOTO • DIXIE • DUVAL • • JEFFERSON • INDIAN RIVER JACKSON • HOLMES • HILLSBOROUGH • HERNANDO HIGHLANDS • HARDEE HENDRY • GULF HAMILTON • GLADES • GILCHRIST • FRANKLIN GADSDEN • FLAGLER ESCAMBIA 67 Reasons To Love Florida: A COUNTY GUIDE OSCEOLA • PALM BEACH • PASCO • PINELLAS • POLK • PUTNAM • ST. JOHNS • ST. LUCIE • SANTA ROSA • SARASOTA • SEMINOLE • SUMTER • SUWANNEE • TAYLOR • UNION • VOLUSIA • WAKULLA • WALTON • WASHINGTON • WALTON • WAKULLA • UNION VOLUSIA • TAYLOR • SEMINOLE SUMTER SUWANNEE • SARASOTA ROSA • SANTA LUCIE JOHNS • ST. • POLK PUTNAM ST. • PINELLAS • PASCO BEACH • PALM OSCEOLA • ORANGE • OKEECHOBEE • OKALOOSA • NASSAU • MONROE • MIAMI-DADE • MARTIN • MARION • MANATEE • MADISON • LIBERTY • LEVY • LEON • LEE • LAKE • LAFAYETTE T rend Florida WELCOME! www.FloridaTrend.com Publisher David G. Denor Executive Editor Mark R. Howard EDITORIAL Writer Janet Ware Managing Editor John Annunziata Welcome to Florida Trend’s newest publication—“67 Reasons ADVERTISING Senior Market Director / Central Florida & North Florida to Love Florida.” Orlando - Treasure Coast - Gainesville - Brevard County Jacksonville - Tallahassee - Panama City - Pensacola Laura Armstrong 321/430-4456 You’ve probably already guessed that those 67 reasons match the Senior Market Director / Tampa Bay Tampa - St. Petersburg - Sarasota - Naples - Ft. Myers number of counties in the State of Florida. For each county, Florida Christine King 727/892-2641 Senior Market Director / South Florida Trend has compiled the most relevant details including population, Miami - Ft. Lauderdale - Palm Beaches density, county seat, major cities, colleges, hospitals, and Andreea Redis-Coste 954/802-4722 Advertising Coordinator transportaton options. Rana Becker 727/892-2642 Since Florida Trend is a business magazine, you won’t be surprised we list the size of the labor force, top industries, and major companies. -

Appendix F. Dr. and Mrs. Brent Moelleken – Full Letter

SAN BERNARDINO COUNTYWIDE PLAN FINAL PROGRAM EIR COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO Appendix Appendix F. Dr. and Mrs. Brent Moelleken – Full Letter The full letter can be accessed at the Countywide Plan website at www.countywideplan.com/EIR. August 2020 SAN BERNARDINO COUNTYWIDE PLAN FINAL PROGRAM EIR COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO Appendix This page intentionally left blank. PlaceWorks August 15, 2019 BY EMAIL Jerry L. Blum, Countywide Plan Coordinator - Land Use Services Department County of San BernArdino 385 N. ArrowheAd Avenue, 1st Floor San BernArdino, CA 92415 Re: Comments on Draft Environmental Impact Report DeAr Mr. Blum: This letter is written on behAlf of Dr. and Mrs. Brent Moelleken, owners of a property locAted in Lake ArrowheAd, County of San BernArdino, CaliforniA. The Moelleken’s property is known as ShAdy Cove. ShAdy Cove is on the NationAl Registry of Historic properties, and it is subject to an easement with restrictive covenAnts. The purpose of these comments is to provide evidence and request thAt the DrAft EnvironmentAl ImpAct Report (DEIR) be supplemented with additional anAlysis of the impActs of the County of San BernArdino continuing to fail to adopt Mills Act ordinAnces to preserve its historic properties. Along with this letter is a Dropbox link with supporting documentAtion. We would be happy to work with your teAm in supplementing the DEIR on these points. The Moellekens, along with many other orgAnizAtions, are committed to ensuring thAt valuAble historic resources are preserved given the aesthetic, environmentAl and economic benefits they confer on neighborhoods and, conversely, the negAtive impActs thAt ultimately occur when these structures deteriorAte and/or are demolished. -

EL GAUCHO Uiban Crises-Hitch Vol

Use UC To Combat EL GAUCHO Uiban Crises-Hitch Vol. 48 - No. 130 Santa Barbara, California Monday, May 20,1968 By RICK ROTH student recruitment program. EG Staff Writer Calling his special report "a part of a very rapid upward Calling for "a University that slope on the part of the Uni is as large in spirit as these versity (concerning minority times demand/* U.C. President aid),” Hitch expressed the hope Charles Hitch presented a that his proposal would "cause broadly based special report an increase in momentum, if advocating a mobilization of possible.” University of California re The U.C. President empha sources to combating Ameri sized "research, public ser ca ’ s urban crises to the Board vice, and education” as the of Regents Friday in the UCen areas in which the University Program Lounge. should take action. He said that ASUCSB President Greg Sta- he has asked the heads of Cali mos and ASUCD President Steve fornia’s public and private col Woodside also presented pro leges and universities, as well posals to the Board on behalf as federal and state agencies o f their respective student bo and public secondary school dies. It appeared, however, that officials, to join U.C. in find the Regents rejected the two ing out "what must and can be student proposals (both of which done” to offer minority groups called for the appointment of the opportunity for higher edu- advisory committees composed cation. of various administrators, fac ulty members, and students), in UCEN LUNCH CROWD— Part of the 200 Davis and Santa Barbara students who waited over three favor of the plan set forth in IN GRIPS OF CRISIS hours to gain admission to the General Session of the Regents Meeting Friday afternoon. -

Arbiter, October 2 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 10-2-1996 Arbiter, October 2 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. ,j, 2.NS.DE ~ ---------WEONESOAY, oaOSER2" 1996 THEARBITER IIflJD~@;;\:,"~~~~:f(~ We are impressed with the amount of '.> .Lett~r.s to the Editor received from stu. "'" •••...•...• Candy machines all over campus reject ~ dents in recent weeks. We value your /&~. the most crisp dollar bills. Can't the uni- 49input, whether it is favorable or unfavor. ,k'0 versity get that fixed? Starving students ~ able to The Arbiter. We'd like to otfer.specla! who need a Snickers to get through their evening thanks to those who have participated in surveys classes are forced to purchase a Coke in order to published in the HBF and Hootenanny sections. get change. .The Arbiter is disappointed by the The Arbiter has noticed the efforts of lack of tact shown by some members .., ~ ASBSU President Dan Nabors and Vice of the media pertaining to the current ~. President Stuth Adams to reach out ~o ~ situation of the Bronco Football team. students by conducting two press conferences 10 as In a recent press conference with new Head many weeks at heavily trafficked areas of campus. -

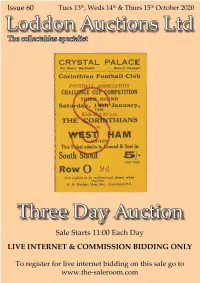

Issue 60 Email Version-1.Pdf

DAY 1, TUESDAY 13th OCTOBER, LOTS 1-500 Lot Description Estimate Football programmes, a collection of 23, 1950's, programmes inc. Blackpool v Bolton FAC Final 1953, Burnley v Newcastle FAC 1953/54, Fulham v Airdrie Fr. £60-80 1 1952/53, Leicester v Lincoln 1953/54, Luton v Leicester 1953/54, Leicester v (plus BP*) Hibernian Fr 56/57, Bolton v Manchester Utd 1958/59, Man Utd v Blackburn 1958/59 etc (some with minor faults, gen gd) Football programmes, a selection of 15 Scottish programmes inc. Rangers v Dundee Cup Final 1964, Scotland v England 1960 and 1964, Scotland v Brazil £30-50 2 1966, Scotland v Italy 1965, Hibs. v Motherwell League Cup 1959/60, Hibs v (plus BP*) Celtic 1962/3, Celtic v Tottenham Fr 1967, Celtic v Clyde Scottish Cup semi- final 1st April 67 etc (gen gd) Football programmes, a collection of 15, 1940/50's, programmes inc. Chelsea v Blackpool & Manchester City, both 1947/48, FA Amateur Cup Final 1947 played at Chelsea, Arsenal v Manchester City 1947/48, Fulham v WBA 46/47, £50-60 3 Arsenal v Manchester City 49/50, Manchester City v Barnsley 47/48, Man City (plus BP*) Res v Newcastle Res 49/50, Man City v River Plate Fr 51/52, West Ham v Man City 46/47 single sheet etc (some minor faults but gen gd) Football programmes, a selection of 20, 1940's, programmes inc. Fulham v Southampton 45/46, Fulham v Luton 46/47, Man City v Burnley 46/47, Man £50-60 4 City v Birmingham 48/49, Man City v Man Utd 48/49, Man City v Arsenal (plus BP*) 49/50, Aston Villa Res v Blackpool Res, Derby Res, Newcastle Res, & Leeds Res all 47/48, Derby v Aston Villa 47/48 etc (some minor faults, gen gd) Football programmes, Manchester City, 17 home programmes all 1949/50 season inc.