Making Sense Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

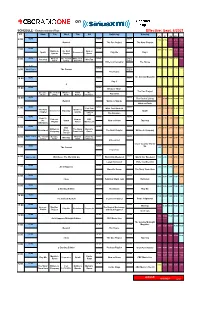

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (Eds.)

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) RIPE @ 2007 NORDICOM From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) NORDICOM From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media RIPE@2007 Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) © Editorial matters and selections, the editors; articles, individual con- tributors; Nordicom ISBN 978-91-89471-53-5 Published by: Nordicom Göteborg University Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG Sweden Cover by: Roger Palmqvist Cover photo by: Arja Lento Printed by: Livréna AB, Kungälv, Sweden, 2007 Environmental certification according to ISO 14001 Contents Preface 7 Jo Bardoel and Gregory Ferrell Lowe From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. The Core Challenge 9 PSM platforms: POLICY & strategY Karol Jakubowicz Public Service Broadcasting in the 21st Century. What Chance for a New Beginning? 29 Hallvard Moe Commercial Services, Enclosure and Legitimacy. Comparing Contexts and Strategies for PSM Funding and Development 51 Andra Leurdijk Public Service Media Dilemmas and Regulation in a Converging Media Landscape 71 Steven Barnett Can the Public Service Broadcaster Survive? Renewal and Compromise in the New BBC Charter 87 Richard van der Wurff Focus on Audiences. Public Service Media in the Market Place 105 Teemu Palokangas The Public Service Entertainment Mission. From Historic Periphery to Contemporary Core 119 PSM PROGRAMMES: strategY & tacticS Yngvar Kjus Ideals and Complications in Audience Participation for PSM. Open Up or Hold Back? 135 Brian McNair Current Affairs in British Public Service Broadcasting. Challenges and Opportunities 151 Irene Costera Meijer ‘Checking, Snacking and Bodysnatching’. -

Confidential Draft V5

CBC/Radio-Canada First Quarter Financial Report 2012-2013 0 CBC/Radio-Canada First Quarter Financial Report 2012-2013 Confidential Draft 5 March 1, 2013 10:58 AM CBC/Radio-Canada Second Quarter Financial Report 2012-2013 1 CBC/Radio-Canada Second Quarter Financial Report 2012-2013 CBC/Radio-Canada Second Quarter Financial Report 2012-2013 Table of Contents CBC/Radio-Canada’s Commitment to Transparency and Accountability ..................................................... 3 Management Discussion and Analysis ......................................................................................................... 4 Quarter in Review ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Financial Highlights .............................................................................................................................. 5 Business Highlights.............................................................................................................................. 8 1. Performance Update .......................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Strategic Indicators ................................................................................................................ 11 1.2 Operational Indicators ........................................................................................................... 13 2. Capability to Deliver Results ............................................................................................................. -

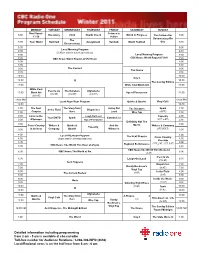

Radio One Winter 2011 Mainlandnsoutside905.XLS

Mainland NS - outside 90.5 FM Frequency MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 World Business & Witness Asia Pacific Heart & Soul 5:00 5:30 Daybreak All in the Mind One Planet 5:30 6:00 6:00 Information Morning: Mainland NS 6:30 6:30 Weekend Mornings 7:00 CBC News: World Weekend Mornings 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am Report 6/7/8/9 CBC News: World 7:30 8:00 Report 6/7/8/9 8:00 8:30 Maritime Magazine 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 Q 10:30 The Sunday Edition 11:00 White Coat Black Art 11:00 White Coat C'est la vie The Debaters Backbencher 11:30 Black Art Age of Persuasion 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Maritime Noon Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from The Bottom Spark 1:00 In the Field Dispatches The Debaters 1:30 Chapter Here Line Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Laugh Out Loud 2:00 Your DNTO Spark Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Age of Persuasion 2:30 Definitely Not The 3:00 Opera 3:00 Close to Home Writers & Company 3:30 3:30 4:00 4:00 Mainstreet Mainland NS The Next Chapter All The Best 4:30 4:30 5:00 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Atlantic Airwaves 5:30 5:30 Cross Country CBC News: The World at Six 6:00 Checkup 6:00 A Propos 6:30 6:30 As It Happens 7:00 CBC News:The World This Weekend 7:00 7:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 7:30 8:00 8:00 The Current Review Randy Bachman's Dispatches 8:30 8:30 Vinyl Tap 9:00 9:00 Ideas In the Field 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 Q Inside the Music 10:30 -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

Radio One Fall 2013 FINAL.Xlsx

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 6:00 6:00 Local Morning Program 6:30 6:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) 7:00 Local Morning Program 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am CBC News: World Report 6/7/8/9 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 Q 10:30 The Sunday Edition 11:00 This Is That 11:00 White Coat C'est la vie The Debaters This Is That White Coat 11:30 Black Art 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) Black Art (3:30 NT) 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next Living Out The Story from The Debaters Spark 1:00 Vinyl Café Stories The 180 Chapter Loud Here (4 PT) 1:30 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Tapestry 2:00 Your DNTO Spark Rewind Canada Live DNTO 2:30 Afternoon (3 PT, 4 MT) 2:30 3:00 3:00 Cross Country Writers & Quirks & And the Writers & Company TapestryTapestry 3:30 iniH an HourC Company QuarksQk WinnerWi Is I Wire Tap (5PT/MT/CT) 3:30 4:00 Local Afternoon Program 4:00 The Next Chapter Cross Country 4:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) 4:30 Checkup 5:00 (1 PT, 2 MT, 3 CT, 5 AT) 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Regional Performance 5:30 5:30 CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six 6:00 (7 AT) C'est la vie 6:30 Laugh Out Loud 6:30 (7:30 AT) As It Happens 7:00 The 180 7:00 Randy Bachman's 7:30 (8 AT) 7:30 Vinyl Tap 8:00 Living Out Loud 8:00 The Current Review (8 AT) 8:30 (9 AT) 8:30 9:00 Inside the Music 9:00 Ideas 9:30 Saturday Night Blues (10 AT) 9:30 10:00 (10 -

Detailed Information Including Programming from 2 Am

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00 6:00 Daybreak Kamloops North by Northwest North by Northwest 6:30 6:30 with host Shelley Joyce with host with host 7:00 Sheryl MacKay Sheryl MacKay 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am 7:30 8:00 CBC News: World CBC News: World 8:00 8:30 Report 6/7/8/9 Report 6/7/8/9 8:30 The Current 9:00 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 The Sunday Edition 10:00 10:00 Q Day 6 10:30 10:30 11:00 This Is That 11:00 White Coat The 180 11:30 C'est la vie The Debaters This is That White Coat Black Art 11:30 Black Art 12:00 PM 12:00 PM B.C. Almanac with host Mark Forsythe Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next Living Out The Story from Ideas in the 1:00 Vinyl Café Stories The Debaters 1:30 Chapter Loud Here Afternoon Cross Country 1:30 2:00 Checkup 2:00 The 180 Your DNTO Spark Rewind Canada Live DNTO 2:30 2:30 3:00 Cross Country Writers & 3:00 Quirks & Quarks Tapestry My Playlist Tapestry 3:30 in an Hour Company WireTap 3:30 4:00 4:00 Radio West The Next Chapter Spark 4:30 4:30 with host Rebecca Zandbergen 5:00 Hot Air 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm with host Writers & Company 5:30 Margaret Gallagher 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Living Out Loud 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review Rewind 8:50 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 Backstage with Ben 10:30 Q 10:30 Hepner 11:00 11:00 This is That 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Vinyl Café Randy A Propos This American Life Quarks Here 11:30 WireTap Bachman's 11:30 Vinyl Tap The Sunday Edition 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition The House 12:00 AM 'Round Midnight 1:00 The World Day 6 World Link 1:00 Detailed information including programming from 2 am - 5 am is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news is on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm. -

Detailed Information Including Programming from 2 Am

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY One Planet - Science in 5:00 Discovery Click Health Check World in Progress The Curious Ear 5:00 17:30 Action Documentary On The 5:30 Your World HardTalk Assignment Hardtalk World Football One 5:30 Documentary 6:00 6:00 Local Morning Program 6:30 6:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) 7:00 Local Morning Program 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am CBC News: World Report 6/7/8/9 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 Q 10:30 The Sunday Edition 11:00 White Coat Black Art 11:00 White Coat C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada 11:30 Black Art Age of Persuasion 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out Spark 1:00 In the Field Dispatches The Debaters 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap (4 PT) 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Laugh Out Loud Tapestry 2:00 Your DNTO Spark Canada Live 2:30 Afternoon Age of Persuasion (3 PT, 4 MT) 2:30 Definitely Not The 3:00 3:00 Cross Country Writers & Quirks & And the Opera Writers & Company Tapestry 3:30 in an Hour Company Quarks Winner Is (5PT/MT/CT) 3:30 4:00 Local Afternoon Program 4:00 The Next Chapter Cross Country 4:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) 4:30 Checkup 5:00 5:00 (1 PT, 2 MT, 3 CT, 5 AT) CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Regional Performance 5:30 5:30 CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six 6:00 (7 AT) C'est la vie 6:30 Laugh Out Loud 6:30 -

Summer 2021 DIGITAL Program Guide

PEOPLE-POWERED RADIO KCSBPROGRAM SCHEDULE ADDRESS:1055- STORKEFM COMMUNICATIONS BUILDING,91.9 BUSINESS TEL: (805) 893-3921 UC SANTA BARBARA, CA 93106 DJ VOICEMAIL: (805) 253-3091 SUMMER 2021 ABOUT US The radio station at the University of California, Santa Barbara, KCSB-FM, is licensed by the Federal Communications Commission to the Regents of the University of California. KCSB is funded primarily by the students at UCSB and the community at large. As a non-commercial, educational FM station broadcasting for the public interest, KCSB enters into no commercial contracts which allow access to the airwaves, and it strives to provide programming substantially different from that carried by commercial broadcast media. It is also designed to be educational for both programmers and listeners. UCSB students and other programmers are provided an opportunity to learn the fundamentals of radio broadcasting. Everyone here at KCSB has worked together to adapt to a new virtual environment, requiring difficult but necessary changes, such as developing remote training programs for DJs, publicity ambassadors, sports volunteers, news volunteers, and KJUCers, as well as remote call- ins to the station through our new DJ voicemail box– call in and leave us a message at (805) 253-3091! 2 3 MEET EXCOMM <3 email us to learn how to get involved! AL SIMPKINS ZENA OMAR DIANA ESCAMILLA SHERRY ZENG GREG SILVER ALEX CASTILLO ASST. PROGRAM DIRECTOR GENERAL MANAGER PROGRAM DIRECTOR DIGITAL MEDIA COORDINATOR SPORTS DIRECTOR ASSISTANT ENGINEER [email protected] [email protected] -

Rethink's Radio Book

THE RADIO BOOK ReThink Media’s guide to the public affairs programs you need to know 2016 Edition The Radio Book ReThink Media’s guide to the public affairs programs you need to know 2016 - First Edition The research for this book was undertaken by ReThink Media staff, fellows, and interns between 2013 and 2015. Although we made every effort to speak directly with a producer of each show we list, we were not always successful. The “Features” tags included with many entries are complete to the best of our abilities—but some shows lack them when we could not be sure of a feature. Similarly, pitching intel is available for shows with which we were able to make contact. We would like to acknowledge Alyssa Goard, Katherine O’Brien, Daniel Steiner, and Lisa Bergstrom, who each had a big hand in bringing this project to completion. Thank you so much for all your hard work! Designed and formatted by ReThink Media. Printed by Autumn Press in Berkeley, CA. Soundwave front cover image designed by Freepik. Table of Contents Introduction 4 Ohio 160 Understanding Radio 5 Oklahoma 165 Pitching Radio 8 Oregon 168 Pennsylvania 171 Nationally Syndicated 11 Rhode Island 175 News 12 South Dakota 176 Feature Stories 22 Tennessee 177 Interviews 38 Texas 181 Utah 187 State and Regional 45 Vermont 192 Alaska 46 Virginia 194 Arizona 49 Washington 196 Arkansas 51 West Virginia 199 California 53 Wisconsin 201 Colorado 67 Wyoming 209 Connecticut 68 District of Columbia 70 Community Radio 210 Florida 73 Georgia 79 Podcasts 221 Hawaii 80 Index 227 Idaho 82 Illinois 84 Indiana 88 Iowa 94 Kansas 98 Kentucky 102 Louisiana 104 Maine 108 Maryland 111 Massachusetts 114 Michigan 117 Minnesota 124 Mississippi 127 Missouri 128 Montana 132 Nevada 134 New Hampshire 136 New Mexico 139 New York 148 North Carolina 157 North Dakota 159 3 Part 1: Introduction Understanding Radio In order to maximize the potential of radio, it’s critical to first understand the landscape. -

Detailed Information Including Programming from 2 Am

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:30 On The Island with host Gregor Craigie 5:30 6:00 North by Northwest North by Northwest 6:00 Daybreak North 6:30 with host with host 6:30 with hosts Leisha Grebinski and Betsy Trumpener 7:00 Sheryl MacKay Sheryl MacKay 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am 7:30 8:00 CBC News: World CBC News: World 8:00 8:30 Report 6/7/8/9 Report 6/7/8/9 8:30 9:00 9:00 The Current The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 10:00 Day 6 The Sunday Edition 10:30 Q 10:30 11:00 This is That 11:00 White Coat 11:30 C'est la vie The Debaters This is That White Coat Black Art 11:30 Black Art 12:00 PM 12:00 PM BC Almanac with host Mark Forsythe Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next Wachtel on the Living Out 1:00 In the Field Vinyl Café Stories The Debaters 1:30 Chapter Arts Loud Cross Country 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Checkup 2:00 Your DNTO Spark Rewind Canada Live DNTO 2:30 Afternoon 2:30 3:00 3:00 Cross Country Writers & And the Quirks & Quarks Tapestry Tapestry 3:30 in an Hour Company Winner Is WireTap 3:30 4:00 4:00 The Next Chapter Spark 4:30 All Points West 4:30 with host Joanne Roberts 5:00 Hot Air 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm with host Writers & Company 5:30 Margaret Gallagher 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 As It Happens 7:00 7:00 In the Field 7:30 Randy Bachman's Vinyl 7:30 8:00 Tap 8:00 The Current Review Living Out Loud 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q Tonic 10:30 10:30 11:00 Trail Breakers Trust, Inc. -

CBC Radio One - Program Schedule Winter 2018-2019

CBC Radio One - Program Schedule Winter 2018-2019 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 6:00 6:00 6:30 Local Morning Program 6:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) Local Morning Program 7:00 CBC News: World Report 7:00 7:30 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am at 6/7/8/9 am 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current The The Sunday 9:00 9:30 House Edition 9:30 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 q 10:30 11:00 Because News 11:00 The Doc Project The Debaters 11:30 Because News Under The Short Cuts Under The 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) Influence Influence 12:00 PM Out 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks in the 12:30 Open 12:30 1:00 The Next The Doc Project White Coat 1:00 Unreserved Tapestry Out in the Spark 1:30 Chapter Open Laugh Out Loud The Debaters (4 PT) 1:30 Podcast Now or 2:00 Ideas in the Playlist 2:00 Spark Never Canada Podcast Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Live Playlist (3 PT, 4 MT) 2:30 Writers & 3:00 Writers & Quirks & Marvin’s Writers & 3:00 MyReclaimed Playlist Story From Here Now or Never Company 3:30 Company Quarks Room Company(5 CT, MT, PT) 3:30 Cross 4:00 Local Afternoon Program The Next Country 4:00 4:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) Chapter Checkup 4:30 (1 PT, 2MT, 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Regional 3CT, 5AT) 5:00 5:30 Performance 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News: The World This Weekend (7 AT) 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud White Coat 6:30 7:00 As It Happens Unreserved 7:00 7:30 Randy Bachman’s (8 AT) 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review (8 AT) Reclaimed 8:30 (9