Self-Pollination Effects on Douglas-Fir And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

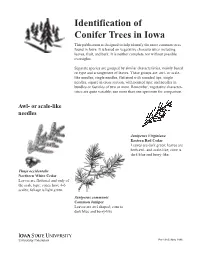

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Pinus Resinosa Common Name: Red Pine Family Name: Pinaceae –

Plant Profiles: HORT 2242 Landscape Plants II Botanical Name: Pinus resinosa Common Name: red pine Family Name: Pinaceae – pine family General Description: Pinus resinosa is a rugged pine capable of withstanding extremes in heat and cold. Native to North America, the Chicago region is on the southern edge of its range where it is reported only in Lake and LaSalle counties. Red pine does best on dry, sandy, infertile soils. Although red pine has ornamental features, it is not often used in the landscape. There are a few unique cultivars that may be of use in specialty gardens or landscapes. Zone: 2-5 Resources Consulted: Dirr, Michael A. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants: Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. Champaign: Stipes, 2009. Print. "The PLANTS Database." USDA, NRCS. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA, 2014. Web. 21 Jan. 2014. Swink, Floyd, and Gerould Wilhelm. Plants of the Chicago Region. Indianapolis: Indiana Academy of Science, 1994. Print. Creator: Julia Fitzpatrick-Cooper, Professor, College of DuPage Creation Date: 2014 Keywords/Tags: Pinaceae, tree, conifer, cone, needle, evergreen, Pinus resinosa, red pine Whole plant/Habit: Description: When young, Pinus resinosa has the typical pyramidal shape of most pines. When open grown, as in this image, the branches develop lower on the trunk creating a dense crown. Notice the foliage is concentrated in dense tufts at the tips of the branches. This is characteristic of red pine. Image Source: Karren Wcisel, TreeTopics.com Image Date: September 27, 2010 Image File Name: red_pine_2104.png Whole plant/Habit: Description: Pinus resinosa is often planted in groves to serve as a windbreak. -

Selection and Care of Your Christmas Tree

Selection and Care of Your Christmas Tree People seldom realize that a Christmas tree is not a timber tree whose aspirations have been frustrated by an untimely demise. It is realizing its appointed destiny as a living room centerpiece symbolic of "man's mystic union with nature." Moreover, while it grows, it provides cover for a variety of wildlife, enhances rural beauty, contributes to the local economy and helps to purify the atmosphere by absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. A large selection of Christmas trees is available to New York residents. Most of the trees are grown in plantations, but some still come from natural forest areas. Only the few species of trees that are commercially significant will be discussed in this bulletin. Selecting a Tree One of the joys of the Yule season can be selecting and cutting a tree. Many Christmas tree growers in New York State are willing to let the purchaser do so himself. Also, Christmas tree growers usually have a good selection of freshly cut trees at roadside stands. Such facilities assure you of fresh trees rather than trees that were cut some time ago and shipped long distances. "Freshness," however, relates to a tree's moisture content. With favorable storage and atmospheric conditions, a tree can still contain adequate moisture many weeks after harvest. Some growers control moisture loss from their products by applying a plastic anti-transpirant spray to the growing trees just prior to harvest. In New York, Christmas trees can be divided into two main groups: the short-needled spruces and firs and the long- needled pines. -

Structure, Development, and Spatial Patterns in Pinus Resinosa Forests of Northern Minnesota, U.S.A

Structure, development, and spatial patterns in Pinus resinosa forests of northern Minnesota, U.S.A. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Emily Jane Silver IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Anthony W. D’Amato Shawn Fraver July 2012 © Emily J. Silver 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge many sources of inspiration, guidance, and clarity. First, I dedicate this manuscript to my co-advisors Dr. Anthony W. D’Amato and Dr. Shawn Fraver. I thank Tony for supporting my New England nostalgia, for endless patient explanations of statistical analyses, for sending me all over the state and country for enrichment opportunities, and advising me on the next steps of my career. To Shawn, my favorite deadwood-dependent organism, for countless hours in the field, persistent attention to timelines, grammar, details, and deadlines, and for career advice. I would like to thank Dr. Robert Blanchette, the most excited and knowledgeable third committee member I could have found. His enthusiasm and knowledge about mortality agents and fungi of the Great Lakes region helped me complete a very rewarding aspect of this research. Second, to the colleagues and professionals who provided ideas, snacks, drinks, and field work assistance: Miranda and Jordan Curzon, Paul Bolstad, Salli and Ben Dymond, Paul Klockow, Julie Hendrickson, Sascha Lodge, Justin Pszwaro, Eli Sagor, Mike Reinekeinen, Mike Carson, John Segari, Alaina Berger, Jane Foster, and Laura Reuling. Third to Dr. Tuomas Aakala (whose English is better than my own) for good humor, expertise, and patience coding in R and conceptualizing the spatial statistics (initially) beyond my comprehension. -

Verbenone Protects Chinese White Pine (Pinus Armandii)

Zhao et al.: Verbenone protects Chinese white pine (Pinus armandii) (Pinales: Pinaceae: Pinoideae) against Chinese white pine beetle (Dendroctonus armandii) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) attacks - 379 - VERBENONE PROTECTS CHINESE WHITE PINE (PINUS ARMANDII) (PINALES: PINACEAE: PINOIDEAE) AGAINST CHINESE WHITE PINE BEETLE (DENDROCTONUS ARMANDII) (COLEOPTERA: CURCULIONIDAE: SCOLYTINAE) ATTACKS ZHAO, M.1 – LIU, B.2 – ZHENG, J.2 – KANG, X.2 – CHEN, H.1* 1State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources (South China Agricultural University), Guangdong Key Laboratory for Innovative Development and Utilization of Forest Plant Germplasm, College of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China 2College of Forestry, Northwest A & F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; phone/fax: +86-020-8528-0256 (Received 29th Aug 2020; accepted 19th Nov 2020) Abstract. Bark beetle anti-aggregation is important for tree protection due to its high efficiency and fewer potential negative environmental impacts. Densitometric variables of Pinus armandii were investigated in the case of healthy and attacked trees. The range of the ecological niche and attack density of Dendroctonus armandii in infested P. armandii trunk section were surveyed to provide a reference for positioning the anti-aggregation pheromone verbenone on healthy P. armandii trees. 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after the application of verbenone, the mean attack density was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group (P < 0.01). At twelve months after anti-aggregation pheromone application, the mortality rate was evaluated. There was a significant difference between the control and treatment groups (chi-square test, P < 0.05). -

RED PINE Snowshoe Hares Browse Songbirds, Mice and Pinus Resinosa Soland

colorful bark. This species provides cover for many species of mammals and birds. Deer, cottontails, and RED PINE snowshoe hares browse songbirds, mice and Pinus resinosa Soland. chipmunks feed on the seed while seedlings. Plant symbol = PIRE Agroforestry: Pinus resinosa is used in tree strips for windbreaks. They are planted and managed to Contributed By: USDA, NRCS, National Plant Data protect livestock, enhance crop production, and Center control soil erosion. Windbreaks can help communities with harsh winter conditions better handle the impact of winter storms and reduce home heating costs during the winter months and cooling cost in the summer. Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status and wetland indicator values. Description General: Red pine (Pinus resinosa) is a medium sized tree, up to twenty-five meters high and seventy- five centimeters in diameter (Farar 1995). The leaves are soft and flexible evergreen needles, in clusters of two, slender, 4”-6” long, dark green borne in dense tufts at the ends of branchlets. The fruit is ovoid- conic, with thin scales, becoming light chestnut- brown at maturity. The bark is thick and slightly divided by shallow fissures into broad flat ridges covered by thin loose red-brown scales (Sargent 1961). The root system is moderately deep, wide spreading, and very wind firm. Distribution: Red pine is native to northeastern © Joseph O’Brien USDA, Forest Service, St. Paul Field Office United States. This species ranges from Newfoundland and Manitoba, south to the mountains Alternate Names of Pennsylvania, west to Minnesota (Dirr 1990). -

Red Pine Pinus Resinosa

red pine Pinus resinosa Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Coniferophyta The red pine is also known as the Norway pine, but Class: Pinopsida it is a native of North America. This tree may grow to Order: Pinales 150 feet tall with a trunk diameter of three feet. Its crown is pyramid-shaped. The red-brown bark is Family: Pinaceae divided into plates. The dark-green needles, ILLINOIS STATUS arranged in clusters of two, may be six inches long. The male (staminate) flowers are in purple spikes up common, native to one-half inch long. The female (pistillate) flowers © Guy Sternberg are in red clusters. The fruit is an ovoid cone, about two inches long. The cone scales are smooth. The triangular seed may be up to one-eighth inch long with a wing about three-fourths inch long. BEHAVIORS The red pine may be found in north-central Illinois. It grows in dry, rocky woods. Its wood is used in building ships and bridges and for general construction. tree ILLINOIS RANGE bark © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. male reproductive structures female reproductive structures cone © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Aquatic Habitats none Woodland Habitats coniferous forests Prairie and Edge Habitats none © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources.. -

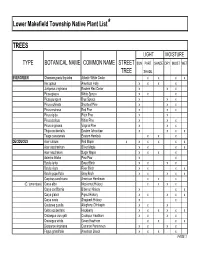

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Red Pine Is Native to the North- Eastern United States and Adjacent Areas in Canada

Forest An American Wood Service Red United States Department of Agriculture Pine FS-255 Red pine is native to the North- eastern United States and adjacent areas in Canada. It is a long-lived species with some stands reaching 200 years of age. The American bald eagle often builds its nests in large old-growth red pine trees. The wood is easy to work with hand tools and holds nails and screws well. It is primarily used for structural pur- poses, but is also used for outdoor furniture and toys. Red pine is a popular Christmas tree. Figure 1.—Red pine. F-529546 An American Wood Red Pine (Pinus resinosa Ait.) Edwin Kallio and John W. Benzie1 Distribution Red pine (Pinus resinosa Ait.) (fig. 1) is a native tree in the Lake States, New England, New York, Pennsyl- vania, and adjacent areas in Canada. It also grows locally in West Virginia and northern Illinois. The most exten- sive stands of red pine are in the northern Lake States and southern Ontario, where the tree is commonly found on level and gently rolling sand plains. Further east, red pine stands generally cover smaller areas and are found not only on outwash plains, but also on mountain slopes and hilltops. Although red pine occurs from sea level to more than 2,000 feet elevation, it is most common between 700 and 1,400 feet. The commercial range of red pine is a relatively narrow area a few hundred miles wide along the United States and Canadian border from the Great Plains to the Atlantic Ocean (fig. -

An Analysis of the Vascular Flora of Annapolis Heathlands, Nova Scotia

12_05055_flora.qxd 11/1/07 11:11 AM Page 351 An Analysis of the Vascular Flora of Annapolis Heathlands, Nova Scotia S. CARBYN1, P. M. CATLING2, S. P. VANDER KLOET3, and S. BASQUILL4 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Environmental Health, Biodiversity, 32 Main Street, Kentville, Nova Scotia B4N 1J5 2 Agriculture and AgriFood Canada, Environmental Health, Biodiversity, Saunders Bldg., Central Experimental Farm, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 Canada; e-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia B4P 2R6 Canada 4Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre, PO Box 6416, Sackville, New Brunswick E4L 1G6 Canada; e-mail: sbasquill@ mta.ca Carbyn, S., P. M. Catling, S. P. Vander Kloet, and S. Basquill. 2006. An analysis of the vascular flora of Annapolis Heath- lands, Nova Scotia. Canadian Field-Naturalist 120(3): 351–362. A description and analysis of the vascular plant composition of heathlands in the Annapolis valley were undertaken to pro- vide a basis for biodiversity preservation within a system of protected sites. Species presence and abundance were recorded at 23 remnant sites identified using topographic maps, air photos, and Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources records. A total of 126 species was recorded, of which 94 were native and 31 introduced. The Annapolis heathland remnants are strongly dominated by Corema conradii with Comptonia peregrina, Vaccinium angustifolium and Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum. A number of species, including Solidago bicolor, Carex tonsa var. rugosperma, Dichanthelium depauperatum, Lechea intermedia, Melampyrum lineare, and Rubus hispidus, were characteristic of heathland remnants, although they usu- ally contributed little to the total cover. -

Stand and Cohort Structures of Oldgrowth Pinus

Journal of Vegetation Science 23 (2012) 249–259 Stand and cohort structures of old-growth Pinus resinosa-dominated forests of northern Minnesota, USA Shawn Fraver & Brian J. Palik Keywords Abstract Coarse woody debris; Dendrochronology; Forest disturbance; Red pine; Reference Questions: What is the natural range of variability in stand and age structure of conditions; Stand dynamics; White pine; old-growth Pinus resinosa-dominated forests? Does the spatial pattern of tree ages Wildfire provide insights into past disturbances that structured these forests? Abbreviation Location: Old-growth P. resinosa forests at seven sites in Minnesota, USA. DWD = down woody debris. Methods: We applied detailed dendrochronological methods to living and dead Received 8 June 2011 material to reconstruct stand and age structures prior to European settlement of Accepted 17 August 2011 the region. We linked dendrochronological data to mapped stem locations to Co-ordinating Editor: Kerry Woods shed light on spatial patterns of past disturbance. Results: Data pooled across sites revealed a mean living tree basal area of Fraver, S. (corresponding author, sfraver@fs. 34.8 m2·haÀ1, snag basal area of 6.9 m2·haÀ1 and down woody debris (DWD) fed.us) & Palik, B.J. ([email protected]): US volume of 100 m3·haÀ1. Living tree diameter distributions varied between Forest Service, Northern Research Station, sites; however, at all sites, smaller diameter classes were dominated by non- Grand Rapids, Minnesota, 55744, USA pines, many pre-dating the onset of fire suppression in the 1920s. There were a variety of P. resinosa age structures, including one-cohort, two-cohort (at times with additional sporadic recruitment) and three-cohort stands. -

Native Plant List TABLE 1: Species for Tree and Shrub Plantings Trees For

Native Plant List TABLE 1: Species for Tree and Shrub Plantings Trees for Dry-Open Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Betula populifolia Gray Birch 30' Juniperis virginiana Eastern Red Cedar 10-75' Pinus resinosa Red Pine 70' Pin us rigida Pitch Pine 50' Pinus stro bus White Pine 80' Quercus rubra Red Oak 70' Quercus coccinea Scarlet Oak 70' Quercus velutina Black Oak 70' Shrubs for Dry-Open Sites Scientific Name 'Common Name Mature Height Amelanchier canadensis Shadbush 15' Ceanothus americanus New Jersey Tea 4' Comptonia peregrina Sweetfern 4' Cornus racemosa Gray Dogwood 6-10' Gaylussacia baccata Black Huckleberry l' Hypericum prolificum Shrubby St. Johnswort 4' Juniperus communis Pasture Juniper 2' Myrica pensylvanica Bayberry 6' Prunus maritima Beach plum 6' Rhus aromatica Fragrant Sumac 3' Rhus copallina Shining Sumac 4-10' Rhus glabra Smooth Sumac 9-15' Rosa carolina Pasture Rose 3' Rosa virginiana Virginia Rose 3' Spirea tomentosa Steeplebush 3-4' Viburnum dentatum/recognitum Arrowwood 5-8' Viburnum lentago Nannyberry 15' Shrubs For Dry-Shady Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Hamamelis wrginiana Witch Hazel 15' Kalmia latifolia Mountain Laurel 3-8' Rhododendron nudiflorum Pinxterbloom Azalea 4-6' Vaccinium angustifolium Lowbush Blueberry 2' Viburnum dentatum Arrowwood 5-8' Trees For Moist Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Acer rubrum Red Maple 60' Betula nigra River Birch Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash 60' Picea mariana Black Spruce 40' Picea