This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Learning Languages

Министерство образования и науки кыргызской республики кыргызско-российский славянский университет кафедра теории и практики английского языка и межкультурной коммуникации о.Ю. Шубина, в.Ш. Хасанова, н.в. курганова PROBLEMS OF LEARNING LANGUAGES учебное пособие для студентов старших курсов языковых специальностей бишкек 2010 уДк 80/81 ббк 81 Ш 95 рецензенты: в.Д. асанов, доц., р.и. кузьмина, доц., г.а. вишневская, доц. рекомендовано к изданию кафедрой теории и практики английского языка и межкультурной коммуникации и ученым советом крсу Допущено Министерством образования и науки кыргызской республики в качестве учебного пособия для студентов высших учебных заведений Шубина О.Ю и др. Ш 95 Problems of learning languages: учебное пособие для студентов страших курсов языковых специальностей / о.Ю. Шубина, в.Ш. Хасанова, н.в. курганова. – б.: крсу, 2010. – 118 с. isbn 978-9967-05-573-5 настоящее учебное пособие “Problems of learning languages” предназнача- ется для студентов старших курсов языковых специальностей. Цель пособия – совершенствование навыков чтения, развитие навыков ре- чевого общения, введение и закрепление лексики по изучаемой теме. пособие состоит из четырех разделов, в каждый из которых включены тематические тексты, определенные задания по различным видам чтения (по- исковое, просмотровое и др.), задания на лексику, задания, направленные на развитие навыков написания аннотаций и эссе. в пособие включены также ролевые игры и тестовые задания для контроля знаний студентов: лексические тесты, тесты к видеофильмам и аудиотесты. в пособие включен словарь-минимум, охватывающий лексику всего мате- риала пособия. задания, предлагаемые в сборнике, предполагают парный и групповой виды работ и предназначены как для аудиторной, так и для самостоятельной работы. Ш 4602000000-09 уДк 80/81 ББК 81 isbn 978-9967-05-573-5 © крсу, 2010 CONTENTS Unit I. -

December 7, 1967

112th Year, No. 33 ST. JOHNS, MICH. — THURSDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 34 PAGES 15 Cents County won't H decline federal money for EOC A formal attempt to "decline* federal money for the construction of the civil defense emer gency operating center in the Clinton County Courthouse was defeated by the .board of supervisors Monday. Supervisor Derrill Shinabery oU Greenbush Township introduced a resolution that the board ,decline to accept the federal participating costs and that the federal government be reimbursed the money that it has expended, to date for additional architectual fees (reportedly about $I,,084). The resolution garnered the votes of seven supervisors, but the other 13 present at the meet ing turned it down. The result seemed to be that the board will go along and accept federal funds, although no such application for the funds was approved. Shinabery told, the board his resolution was not intended to scrap the emergency operating center, but' merely to retain control by the, county over the future use of the emergency operating center portion of the east wing. The resolution was introduced at the board's afternoon session. Early in the morning session, the board heard Capt. Edward A. Lenon, commanding officer of the civil defense division of,the ST. JOHNS HIGH SCHOOL BEGINS TO SHAPE 'UP'ON WEST SICKLES STREET. Michigan State Police, say that there are "no strings attached" The wallsof the passive new St. Johns High School are rising in practically all areas of the'buildtng, located on West. as far as the use of the building SicUles" Streetjn St. -

Catalogue 2014

1 CONTENT 11 JURY 43 ANIMASAURUS REX: COMPETITION OF SHORT ANIMATED FILMS 83 PLANKTOON: COMPETITION OF FILMS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 123 SUPERTOON SUPERTUNES: COMPETITION OF ANIMATED MUSIC VIDEOS 187 COMPETITION OF ANIMATED COMMERCIALS 211 COMPETITION OF ANIMATED OPENING TITLES 217 WORLD PANORAMA 225 CROATIAN PANORAMA 233 SIDE PROGRAMME: CARTOON D’OR 239 SIDE PROGRAMME: EROTICA IN FILMS BY ZAGREB SCHOOL OF ANIMATED FILM 251 SIDE PROGRAMME: EXHIBITION: WALTER NEUGEBAUER 259 SIDE PROGRAMME: ANIMATIC WORKSHOP FOR CHILDREN 265 SIDE PROGRAMME: ANNECY INTERNATIONAL ANIMATED FILM FESTIVAL 273 SIDE PROGRAMME: ZAGREB SCHOOL OF ANIMATED FILM COMMERCIALS 279 SIDE PROGRAMME: CONTEMPORARY TURKISH ANIMATED FILM 287 SIDE PROGRAMME: DVEIN 293 SIDE PROGRAMME: SOUND & VISION - POLISH VERTIGO 307 THE FESTIVAL WELCOME INTRO Supertoon is growing – for four years we have been experts: Efe Efeoglu (Turkey), Darko Vidačković (Croatia), Dear reader, dear friend of animation – welcome to celebrating animation for you! Olga Bobrowska (Poland), Daniel Šuljić (Croatia) and Chintis Supertoon, welcome to Šibenik! Lundgren (Estonia). The Jury will choose best works from Four years are behind us already and we feel as if the all five categories whose authors will get an award and a The Organization Team of Supertoon. Supertoon story began only yesterday. We are looking memory – a sculpture madee by an academic sculptor forward to each and every visitor, guest, accidental Vinko Pešorda. passer-by... and we are sending this joy to our organization team because we got even -

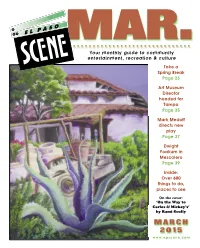

El Paso Scene USER's GUIDE

MAR. • • • • •Y o• u•r •m • o•n •t h•l y• g• u•i d• e• t•o • c•o •m •m • u•n •it y• • • • • entertainment, recreation & culture Take a Spring Break Page 23 Art Museum Director headed for Tampa Page 35 Mark Medoff directs new play Page 37 Dwight Yoakum in Mescalero Page 39 Inside: Over 600 things to do, places to see On the cover: ‘On the Way to Carlos & Mickey’s’ by Rami Scully MARCH 2015 www.epscene.com The Marketplace at PLACITA SANTA FE In the n of the Upper Valley 5034 Doniphan 585-9296 10-5 Tues.-Sat. 12:30-4:30 Sun. Antiques Rustics Home Decor Featured artist for March Fine Art Tamara Michalina Collectibles of Tamajesy Roar Pottery Art Sale & Demonstrations Florals March 28-29 STAINED GLASS Saturday: Bead Crocheting Sunday: Needle Felting Linens Jewelry Jewelry designer Tamara Michalina works in all varieties of beads and other materials to make unique creations. Folk Art Her work will be for sale March 28-29, along with kits to make your own! She wearables also will give demonstrations both days. & More Information: www.tamajesyroar.com • (915) 274-6517 MAGIC BISTRO Indoor/Outdoor Dining Antique Lunch 11 am-2:30 pm Tues.-Sun. Traders 5034 Doniphan Dinner 5-10 pm Fri.-Sat. 5034 Doniphan Ste B Live Music! 833-2121 833-9929 Every Friday 6:30 pm - 9:30 pm magicbistroelp.com Ten Rooms of Every Saturday facebook.com/magicbistro Hidden Treasure A Browser’s Paradise! 11:00 am - 2:00 pm • 6:30 pm - 9:30 pm Antiques Collectibles Vintage Clothing Painted Furniture Hats ~ Jewelry Linens ~ Primitives Vintage Toys Nostalgia of Catering • Private Parties All Kinds Page 2 El Paso Scene March 2015 Andress Band Car Show — Andress High attending. -

Paramore After Laughter Full Album Download MQS Albums Download

paramore after laughter full album download MQS Albums Download. Mastering Quality Sound,Hi-Res Audio Download, 高解析音樂, 高音質の音楽. Paramore – After Laughter (2017) [HDTracks FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Paramore – After Laughter (2017) FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/96kHz | Time – 42:38 minutes | 909 MB | Genre: Rock Studio Masters, Official Digital Download – Source: HDTracks | Front Cover | © Fueled by Ramen. After Laughter is the fifth studio album by American rock band Paramore. After Laughter represents a departure from the usual punk pop and alternative rock sound of their previous releases. The album touches on themes of exhaustion, depression and anxiety, contrasting the upbeat and vibrant sound of the record. Upon release, After Laughter received critical acclaim from music critics, who praised the band’s new sonic direction and the 1980’s new wave and synth-pop sound on the album. We know, we know, Paramore isn’t just Hayley Williams. Paramore is a band. But when every roiling, addictive album is directly fueled by the discord of yet another lineup change, you start to wonder: Should the hole left by the most recently departing bandmate be considered an official member of the band? It’s a thought you can’t help but mull over listening to Paramore’s crackling fifth full-length album, 2017’s After Laughter. The lineup this time features Williams, guitarist Taylor York (a member since their 2007 sophomore effort Riot!) and original drummer Zac Farro, returning after an estrangement since 2010. Notably not present here is bassist Jeremy Davis, who left for the second time in a huff of legal disturbances in 2015. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2013 T 05

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2013 T 05 Stand: 15. Mai 2013 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2013 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT05_2013-7 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

MIAF 2014 Catalogue.Pdf

1 DIRECTOR’s ANIMATION MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL 14TH MESSAGE Malcolm TURNER DIRECTOR Melbourne International Animation Festival Life is full of paradoxes. By nature and instinct I possess The year that Chris Landreth (maker of Bingo, Ryan, a passionate faith in democracy and yet I loathe and Sub Conscious Password to name a few) was here, I have virtually no faith whatsoever in the concept of took him out to dinner and we wound up talking about collective decision making. how the festival comes together. Basically I told him I cannot stand people and organisations who cannot or that for me MIAF is 70% about the films, 20% about the Lwill not make decisions. At its worst and largest, it filmmakers and 10% about the audience BUT that the powers, empowers, fuels and funds a veritable army audience sat at the tip of the hierarchy of priorities. of chair warmers, ticket clippers and self-protectors By this, I think I mean that at heart I will program the charged with gathering all the information to be passed films that I think should be shown BUT as the MIAF FESTIVAL up the line in such a form that the person at the far, far milkshake starts foaming, I will start factoring in the distant end of that line can only really say yes or no to audience experience. the “advice” that lands on his or her table, utterly For starters, I definitely believe that as best as can be secure in the knowledge that they gather the glory done, the final selections should approximately represent when the outcome is good or deflect the tomatoes the overall tone and style of the entire submissions using the “I was acting on best advice” shield should collection and I am the only person in the loop foolhardy things not go so well. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 4-11-2013 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2013). The George-Anne. 2609. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/2609 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REAL MEN WEAR HEELS J PAGE 12 ■M Thursday, April 11, 2013 Georgia Southern University THE www.thegeorgeanne.com Volume 83 • Issue 68 GEORGE-ANNE Green-Ashley sweeps SGA elections BY LAUREN GORLA as Vice President of Auxiliary Affairs. served on the executive board as executive Hogan is a sophomore logistics major who The George-Anne staff Green hopes to focus on serving the assistant, which is a hired position. has served in SGA for two years. This will be students by increasing the education on Ashley hopes to work not only with GSU her first executive board position. Last night Georgia Southern University what SGA can do. students, but the community of Statesboro as Hogan’s main focus will be on creating students selected Garret Green and Annalee “I think that this year we’ve done a good well. guidelines for fund requests so that students Ashley for the President and Vice President job at getting out and educating people on "Outreach is important because we affect and organizations have a better idea of what positions respectively for the Student what all SGA has done, but I think we can do our community. -

Hem Tourniquet Download

Hem tourniquet download click here to download Music Video for Tourniquet by Hem www.doorway.ru - download Tourniquet here Directed by. Tourniquet. by Hem. Publication date Language English. See also MusicBrainz (release) [MusicBrainz (release)] ; MusicBrainz (artist) [MusicBrainz (artist)]. Identifier mbida8d62d-9fde-b63f Music Video for Tourniquet by Hem Directed by Jordan Bruner - www.doorway.ru Animated by Greg Lytle - www.doorway.ru and Jordan Bruner Special. Surely you have already downloaded Hem's new song "Tourniquet" for free (free!) at Hem's website (see the previous news update for more information). Now you can hear Hem playing "Tourniquet" live at their December 2, New York show. The sound quality is not perfect, but I couldn't do much better than this. HEM - Tourniquet @ Columbia City Theater, Seattle (09/18/). Download. Hem - Tourniquet (live in New York 2 December ). Download. Hem - Tourniquet - Departure and Farewell. Download. Evanescence - Tourniquet. Download. Tourniquet - Tears of Korah. Download. UPDATE - February 6th New addition to the site - Ukulele chords for the most frequently downloaded songs from rabbitchords! Go here for a look. Welcome to rabbit chords - A collection of chords and tabs from Hem's various stunning albums, Rabbit Songs, Eveningland, No Word From Tom, Funnel Cloud, Twelfth. Formed in , Hem self-released their debut Rabbit Songs in to critical acclaim, establishing. Director: Jordan www.doorway.rug: download. Nearly a decade after releasing its deeply moving and profoundly beautiful album Rabbit Songs, the Brooklyn-based band Hem was on the verge of falling apart. "I actually believed that Hem might never make music together again as a band," songwriter and pianist Dan Messe tells us in an www.doorway.rug: download. -

Sextant May 2013

Outdoor Recreation Club One of Campion’s latest student-led initiatives has been the formation of an Outdoor Recreation Club. Its purpose is to offer bushwalking, camping, four-wheel driving, fishing, and sightseeing opportunities to wanderlustful students. Several 4WD owners have volunteered their vehicles (conditions apply), with a dozen students having made bookings for the first trip to Sofala (via the upper Turon River) and Sunny Corner State Forest on May 3. Trips will be held monthly, according to demand, with overnight options available. Equipment will be BYO or shared, with fuel costs, camping fees etc to be divided amongst the group. Please contact our adventurous chef, Neil Simpson, for more information. Education reforms questioned By Dylan Littler would then be allocated to schools with solution, but also because it requires a greater needs. higher number of teachers, increasing In the last ten years Australian literacy The aim of this increased financial strain on the teaching body, which is has gone from second place support is to bring Australia within the already significantly compromising the internationally to seventh. This has been OECD's (Organisation for Economic Co- acceptance level of teachers, in some accompanied by similar drops in operation) top five countries for literacy. cases lowering the ATAR below 50. mathematics and science. In November Disadvantaged areas have been targeted The threat to teaching standards in 2011, David Gonski submitted a report to in proposals as needing most attention. university graduates is the result of the government on the education system For this reason the Report has suggested another education goal the government known as the Gonski Report. -

Hansard 3 Oct 2000

3 Oct 2000 Legislative Assembly 3259 TUESDAY, 3 OCTOBER 2000 APPLICATION OF SUB JUDICE RULE CJC Inquiry Into Electoral Fraud Mr SPEAKER: Order! I draw the attention of all honourable members to previous Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) Speakers' rulings on the sub judice rule and its read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. application to the Criminal Justice Commission's open inquiry commencing DIVISION BELLS today. In 1991, Speaker Fouras advised the Mr SPEAKER: Order! Honourable House of an opinion from the Solicitor-General. members, we have a technical problem and I will remind members of its contents. It the bells are not ringing. I intend to adjourn the reads— House for 30 minutes to make sure that every "I refer to previous correspondence in member is able to attend the House. Should relation to the Speaker's ruling in respect there be a division, we can then make sure of the CJC investigation into travelling that they are in the area at that time. allowances and expenses claimed by Sitting suspended from 9.32 a.m. till Members of the Legislative Assembly and 10 a.m. now enclose the Solicitor General's opinion on the matter. ASSENT TO BILLS It will be seen that the Solicitor General's opinion is that whilst it is a Mr SPEAKER: Order! Honourable matter for the discretion of the Speaker, members, I have to report that I have received who is personally charged with the from His Excellency the Governor a letter in responsibility of evaluating whether any respect of assent to certain Bills, the contents particular discussions should take place in of which will be incorporated in the records of the House, if statements are to be made Parliament— in the House which would adversely reflect GOVERNMENT HOUSE on the position of particular individuals QUEENSLAND and specifically would suggest guilt of 14 September 2000 criminal offences, then in view of that The Honourable R.