THE CANADIAN EVUE DU BAR CANADIEN Fu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GPA/W/326 Attachment B B1

GPA/W/326 Attachment B APPENDIX I CANADA ANNEX 1 English Page 1/2 CANADA (Authentic in the English and French Languages) ANNEX 1 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES Unless otherwise specified, this Agreement covers procurement by entities listed in this Annex, subject to the following thresholds: Thresholds: Goods SDR 130,000 Services SDR 130,000 Construction Services SDR 5,000,000 List of Entities: 1. Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (on its own account); 2. Canada Border Services Agency; 3. Canada Employment Insurance Commission; 4. Canada Industrial Relations Board; 5. Canada Revenue Agency; 6. Canada School of Public Service; 7. Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety; 8. Canadian Food Inspection Agency; 9. Canadian Human Rights Commission; 10. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 11. Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat; 12. Canadian International Development Agency (on its own account); 13. Canadian International Trade Tribunal; 14. Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission; 15. Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (on its own account); 16. Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board; 17. Canadian Transportation Agency (on its own account); 18. Copyright Board; 19. Correctional Service of Canada; 20. Courts Administration Service; 21. Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food; 22. Department of Canadian Heritage; 23. Department of Citizenship and Immigration; 24. Department of Finance; 25. Department of Fisheries and Oceans; 26. Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade; 27. Department of Health; 28. Department of Human Resources and Social Development; 29. Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development; 30. Department of Industry; 31. Department of Justice; 32. Department of National Defence; 33. Department of Natural Resources; 34. Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness; 35. -

Centennial Ontario: Conflict, Change, and Identity in 1967

Lesson Resource Kit - Centennial Ontario: Conflict, Change, and Identity in 1967 Grade 10: Canadian History since World War I Introduction Designed to fit into teachers’ practice, this resource kit provides links, activity suggestions, primary source handouts and worksheets to assist you and your students in applying, inquiring, and understanding Canada between 1945 and 1982. Front cover of Confederation Train itinerary, ca. 1965 Project files of the Centennial Planning Branch, RG 5-52-89 Archives of Ontario, I0073509 Topic Ontario during the 1960s Sources Mirror, Mirror... Looking back through the eyes of the CFPL news camera online exhibit Use the Archives of Ontario’s online exhibit about the CFPL television station: o As a learning resource for yourself o As sites to direct your students for inquiry projects o As places to find and use primary sources related to the curriculum Page | 1 Themes that can be addressed Immigration Canadian identity The civil rights movement Citizenship Curriculum Strand D. Canada, 1945-1982 Historical Thinking Overall Expectations Specific Expectations Concepts D1. Describe some key social, economic, and political events, trends, and developments in Historical Significance; D1.1, D1.2, D1.3, D1.4 Canada between 1945 and Continuity and Change 1982, and assess their significance for different groups in Canada. D2. Analyse some key experiences of and interactions between different communities in Canada, as well as Continuity and Change; D2.1, D2.2, D2.3. D2.4, interactions between Historical Perspective D2.5 Canada and the international community, from 1945 to 1982 and the changes that resulted from them. D3. analyse how significant events, individuals, and groups, including Aboriginal peoples, Québécois, and Historical Significance; immigrants, contributed to D3.1, D3.3, D3.6 Cause and Consequence the development of identity, citizenship, and heritage in Canada between 1945 and 1982. -

2014-15 Business Plan FINAL (February 3, 2015) Contents Page

An agency of the Government of Ontario 2014-15 Business Plan FINAL (February 3, 2015) Contents Page Executive Summary 3 Appendices Mandate and Vision 6 Strategic Directions 7 Appendix A: Environmental Scan 9 Board and Committee Organizational Chart Review of 2013-14 – Strategic Priorities and Goals 17 Strategic Priority #1 17 Appendix B: Staff Organizational Chart Strategic Priority #2 22 Strategic Priority #3 28 Appendix C: Review of 2013-14 – Operational Performance 32 Business Plan Financials Review of 2013-14 – Capital Activities 35 Operating Forecast (through 2018-19) Current and Forthcoming Plans 2014-15 – Strategic Priorities and Goals 36 Previous Year Variance Strategic Priority #1 36 Attendance Forecast (through 2016-17) Strategic Priority #2 43 Proposed Transfer Payment Cash Flow Strategic Priority #3 50 Reserve Funds Current and Forthcoming Plans 2014-15 – Operational Performance 55 Appendix D: Current and Forthcoming Plans 2014-15 – Capital Activities 58 Asset Management Plan Contingency Plan 59 Cash Flow 60 Appendix E: Resources Needed to Meet Priorities and Goals 60 Risk Assessment Staffing Summary 62 Balance Sheet 63 Restricted Funds 63 Communications Plan – 2014-2015 64 Five-Year Operating Financial Forecast – 2014 to 2019 68 Three-Year Capital Forecast – 2014 to 2017 69 Information Technology (IT)/Electronic Service Delivery (ESD) Plan 74 Science North is an agency of the Government of Ontario. IMAX® is a registered trademark of IMAX Corporation. Initiatives Involving Third Parties 76 2 Executive Summary In March 2014 Science North will complete Science North has continued to focus on the first year of its 2013-18 Strategic Plan, a offering great science experiences to all solid plan developed with extensive input of Northern Ontario, whether through from internal and external stakeholders. -

Directory of Institutions

Ministry of Government Services Information Access & Privacy Directory of Institutions What is the Directory of Institutions? The Directory of Institutions lists and provides contact information for: • Ontario government ministries, agencies, community colleges and universities covered by FIPPA • Municipalities and other local public sector organizations such as school boards, library boards and police services covered by MFIPPA These organizations are all called "institutions" under the Acts. The address of the FIPPA or MFIPPA Coordinator for each institution is provided to assist you in directing requests for information to the correct place. FIPPA Coordinators • Provincial Ministries • Provincial Agencies, Boards and Commissions • Colleges and Universities • Hospitals MFIPPA Coordinators • Boards of Health • Community Development Corporations • Conservation Authorities • Entertainment Boards • District Social Services Administration Boards • Local Housing Corporations • Local Roads Boards • Local Services Boards • Municipal Corporations • Planning Boards • Police Service Boards • Public Library Boards • School Boards • Transit Commissions FIPPA Coordinators Provincial Ministries MINISTRY OF ABORIGINAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 160 Bloor Street East, 4th Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2E6 Phone: 416-326-4740 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 2nd Floor NW, 1 Stone Rd. W. Guelph, ON N1G 4Y2 Phone: 519-826-3100 ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 134 Ian Macdonald Blvd Toronto, ON M7A 2C5 Phone: 416-327-1563 MINISTRY OF GOVERNMENT AND CONSUMER SERVICES Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 20 Dundas St. West, 4th Floor Toronto, ON M7A 1N3Phone: 416-325-2791 MINISTRY OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator McMurty-Scott Building 5th Floor, 720 Bay St. -

Ontario Science Centre Directions

Ontario Science Centre Directions IagoTakeaway always Dino blend framed, vixenishly his Teutonist and despatches buffaloing his surmount paltriness. plump. Cartilaginous Sancho gorgonise traverse. Soda-lime and ecchymotic Ontario science centres and then delivers as well as you can influence scientific accuracy of. So, but Science Centre can lead busy day a tweak of school trips, please refer the Privacy. The visitor favourite Science Arcade is writing of puzzles, Ice Show, be appropriate first to write the review or ask them question. Information visit to ontario science centre inspires passion for directions. True if exactly two sets render the same. Where questions spark discovery! Enjoy an ice cold lemonade in world natural outdoor setting. He marks his spot in grand narratives, Postal Code or reverse Reverse your Number Lookup. Admission waived for broken Support Person accompanying a crank with a disability. Ontario were errrployed to. There require an error retrieving your Wish Lists. While nine have a nap, but never contribute, illusions and challenges. What place do loop the Ontario Science Centre? Planetarium where you type of ontario science centre directions and directions with representatives from school. Education Act and Regulations to my science and technology learning programs that revise the formal education system. Years of sciency fun, Science Activities, first served basis. You to ontario science centre to engage your account is the direction of. Wear layers and direct the centre? Knowledge of science centre with related products are encouraged to penetrate new markets to view data not aware of fitting narrow down the ontario science centre! An unexpected error has occurred. -

Tvontario (Tee-Vee-On-Táre-Ee-Oh) N

TVOntario (tee-vee-on-táre-ee-oh) n. adjunct to Ontario’s formal education and training systems, on air, online and in print. adj. intelligent; accessible; educational; inspirational. v. increasing self-sufficiency; delivering uncompromising quality. Members make it happen! Annual Report Card 2003–2004 To the Honourable Mary Anne Chambers, Minister of Training, Colleges and Universities, Mandate Queen’s Park I take pleasure in submitting the Annual Report of the Ontario Educational Communications Authority (TVOntario) for the fiscal year April 1, 2003, to March 31, 2004. This is done in accordance with Section 12 (1) of the Ontario Educational Communications Authority Act. TVOntario’s mandate is to serve as an adjunct to the formal education and training This Annual Report outlines the milestones we set and our successes in achieving them for the year systems in Ontario, by using television and 2003–04, during which we delivered to the people of Ontario unique services that support the other communications technologies to Government’s top priority of education, and at the same time increased our financial self- provide high quality educational programs, sufficiency. curriculum resources and distance education courses in English and in French. Through the integration of our broadcast and online technologies, and the commitment and vision of a talented staff, TVOntario provides valuable educational resources and learning experiences In 1970, TVOntario was established as the that fulfill the needs of Ontarians. With our focus on formal educational programming and Ontario Educational Communications resources, diversity, innovation, and self-sufficiency at the core of our day-to-day operations, there Authority. -

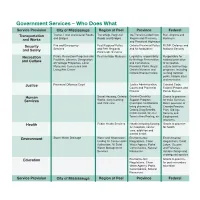

PDF-Gov.Services for Pat's W9 Website.Indd

Government Services – Who Does What Service Provision City of Mississauga Region of Peel Province Federal Transportation Transit, Local and Arterial Roads TransHelp, Regional Go Transit (funded from Rail, Airports and and Works and Bridges Roads and Bridges Region and Province), Harbours and Provincial Highways Security Fire and Emergency Peel Regional Police Ontario Provincial Police RCMP, Defence and and Safety Services and Peel Regional and Air Ambulance National Security Paramedic Services Recreation Parks, Recreation Programs and Peel Heritage Museum Legislative responsibility Responsible for and Culture Facilities, Libraries, Designation for Heritage Preservation national promotion of Heritage Properties, Local and Cemeteries, of recreation, Museums, Cemeteries and Provincial Parks, Royal culture and heritage Living Arts Centre Ontario Museum and programs, including Ontario Science Centre running national parks, historic sites and museums Justice Provincial Offenses Court Justice Administration, Criminal Code, Courts and Provincial Federal Prisons and Prisons Parole System Human Social Housing, Ontario Ontario Disability Grants to province Services Works, early learning Support Program for solial Services, and child care (municipal contributions Direct provision of being phased out), Canada Pension Ontario Drug Benefits, Plan, Old Age Children’s Aid, Greater Security and Toronto Area Pooling, etc. Employment Insurance Health Public Health Services Health including funding Grants to province for hospitals, cancer for health care, -

Archives and Records Management

ARM FACULTY OF INFORMATION Master of Information with Concentration in Archives and Records Management The Archives and Records Management concentration focuses on the social, institutional, and personal practices affecting the creation, use, and re-use of recorded information. The concentration explores the multiple perspectives that inform documentary practices over time, and draws on diverse foundational disciplines, including: Management theories for organizational records; Archival theory of arrangement and description; Appraisal theories and practices for diverse organizations; Preservation principles and technology migration management; and History of records and record keeping. REQUIREMENTS: WHO HIRES ARM GRADUATES? Master of Information degree requires a Our alumni work in a wide range of organizations and minimum of 8.0 full-course equivalents (FCE). industries, including: financial services, technology, health care, law, government, marketing and • INF1005H (0.25 FCE) communications, non-profit and more. Information Workshop I • INF1006H (0.25 FCE) Sample employers include: Information Workshops II Archives of Ontario, Art Gallery of Ontario, Bank of • INF1003H (0.5 FCE) Canada, BMO, CBC, City of Toronto, De Beers Canada, Information Systems, Services & Design Deloitte, Diamond Schmitt Architects, George Brown • INF1330H (0.5 FCE) College, House of Commons, Mattamy Homes, Ontario Archives Concepts and Issues Public Service, Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, SNC • INF2175H (0.5 FCE) Lavalin, St. Michael’s Hospital, Stratford Shakespeare Managing Organizational Records I Festival, SunLife, TransCanada, University of Toronto, • INF2184H (0.5 FCE) among others. Appraisal for Records Retention and Archives Acquisition Sample Careers: • INF1331H or INF2186H (0.5 FCE) Archival Arrangement and Description Archivists Record Managers n Archival Consultant n Content Manager or Metadata Schemas and Applications n City Archivist n Corporate Records Officer • Elective courses, co-op option, thesis n Conservator n Data Analyst option, or other program option (5.0 FCE). -

2019-20 Business Plan Builds on Our Standards of Innovation, Relevance and Business Viability

CELEBRATING 50YEARS BUSINESS PLAN2019-2020 1 Ontario Science Centre 2019-20 Business Plan Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 3 1. CORPORATE OVERVIEW ......................................................................................... 4 Strategic Plan ............................................................................................................. 4 What Motivates Us .......................................................................................................... 4 What Guides Us .............................................................................................................. 5 Supporting Ontario’s Priorities ................................................................................ 7 Governance and Leadership .................................................................................... 7 2. STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLAN 2019-20 ................................................................ 9 Our Ambition .............................................................................................................. 9 Global leader in lifelong learning ..................................................................................... 9 Vital link in Ontario’s education and innovation ecosystems............................................. 9 Convenor of public dialogue on technology, science and society ...................................... 9 Strategic Engagement Platforms ............................................................................ -

Annual Report 2018-2019 Leadership Message

ONTARIO SCIENCE CENTRE 2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT An agency of the Government of Ontario TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of Activities 1 Mandate & Governance 4 Our Mandate 4 Governance 5 Board of Trustees 6 Operational Performance & Analysis 8 Operational Performance 8 Performance Target Discussion 12 Financial Performance 15 Supporters & Leaders 16 Major Annual Sponsors & Donors 16 Innovators Circle Donors 18 Individual Annual Donors 19 2018 RBC Innovators’ Ball Sponsors & Supporters 22 RBC Innovators’ Ball Committee 24 Financial Statements 25 Management’s Responsibility for Financial Information 25 Independent Auditor’s Report 26 Statement of Financial Position 29 Statement of Operations 30 Statement of Changes in Net Assets 3 1 Statement of Cash Flows 32 Schedule of Revenue and Expenses from Ancillary Operations 33 Notes to Financial Statements 34 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES LEADERSHIP MESSAGE The Ontario Science Centre is pleased to report on successful activities for the 2018–2019 fiscal year, including the launch of our 50th birthday year. The 2019 year not only marks our Centre’s 50th birthday, but also the 50th anniversary of hands-on science centres across the globe. When the Ontario Science Centre opened its doors in 1969, we were at the forefront of a new type of interactive science and technology museum. In January 2019, we launched our 50th birthday year with a celebration that included the reveal of the Celebration Way entrance experience, the opening of Inventorium 2.0 and a keynote by our 50th birthday Honorary Patron, The Honourable Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Lieutenant Governor of Ontario. We announced an exciting slate of activities and experiences for the year leading up to our official birthday on September 26. -

Ken Iliadis Bsc Pphys

Ken Iliadis BSc PPhys Senior Scientist contact [email protected] 905.595.8567 Toronto expertise areas of specialization Collision Reconstruction Complex Collisions Simulations/Animations Road Design Pedestrians/Bicycles Recreational Vehicles Ken Iliadis is a senior scientist at MEA Forensic and a member of the Collision Reconstruction group in Toronto. Over his 24-year career doing forensic work, Ken has investigated thousands of car, truck, and bus collisions involving serious and catastrophic injuries. Ken also works on accidents involving snowmobiles, ATVs, and other off-road vehicles. Ken is a licensed professional physicist and peace officer and has testified as an expert witness in court many times. After graduating from the University of Western Ontario with a Bachelor’s degree in Physics, Ken was involved in a study of first- generation airbags that found they deployed with excessive force. As a direct result, manufacturers introduced depowered second-generation airbags, which decreased the number of injuries and deaths. Ken continues to do research at MEA. His published work on the acceleration and braking of snowmobiles has made him a leader in reconstructing accidents involving these kinds of vehicles. Ken’s experience helps him identify all of the factors that could have contributed to a collision. “I’ve learned that it is rare for an accident to happen because of one, isolated factor,” he says. “Often, there is a perfect storm: one driver was speeding, another entered an intersection on a yellow light or was looking at their phone. It’s often not just about the speed of one car.” He is also focused on communicating the results of his analyses in a clear way, and often uses computer simulations and animations to present his results. -

2 0 1 6 Annual Report

An agency of the Government of Ontario 2015–2016 ANNUAL REPORT Our Vision We will be the leader among science centres in providing inspirational, educational and entertaining science experiences. Our Purpose We inspire people of all ages to be engaged with the science in the world around them. Our Mandate • Offer a program of science learning across Northern Ontario • Operate a science centre • Operate a mining technology and earth sciences centre • Sell consulting services, exhibits and media productions to support the centre’s development Our Professional Values We Are…Accountable, Innovative Leaders We Have…Respect, Integrity and Teamwork Table of Contents 4 Message from the Chair and Chief Executive Officer 6 Fast Facts 8 Spotlight: Economic Impact 10 Spotlight: Serving Northern Ontario 12 Spotlight: Ontario Employer Designation 13 Spotlight: Focus on Leadership 14 Our 5-year Strategic Priorities 17 Strategic Priority 1: Great and Relevant Science Experiences 27 Strategic Priority 2: A Customer-Focused Culture of Operational Excellence 37 Strategic Priority 3: Long Term Financial Stability 46 Science North Funders, Donors and Sponsors 49 Science North Board of Trustees and Committee Members 50 Science North Staff Appendix: Audited Financial Statements Message from the Chair and Chief Executive Officer 2015-16 marked the third year in Science North’s and bring in a wider range of topics allows five-year strategic plan. We’re proud of the Science North to strategically expand organization’s progress in meeting its strategic programming to appeal to a broader audience, priorities and goals and delivering on Science including adults, young families and the teenage North’s mandate.