Concert: Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Jeffery Meyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ojai North Music Festival

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival Jeremy Denk Music Director, 2014 Ojai Music Festival Thomas W. Morris Artistic Director, Ojai Music Festival Matías Tarnopolsky Executive and Artistic Director, Cal Performances Robert Spano, conductor Storm Large, vocalist Timo Andres, piano Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Kim Josephson, baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Jennifer Zetlan, soprano The Knights Eric Jacobsen, conductor Brooklyn Rider Uri Caine Ensemble Hudson Shad Ojai Festival Singers Kevin Fox, conductor Ojai North is a co-production of the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances. Ojai North is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Liz and Greg Lutz. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 13 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday, June <D, =;<?, Cpm Welcome : Cal Performances Executive and Artistic Director Matías Tarnopolsky Concert: Bay Area première of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Brooklyn Rider Johnny Gandelsman, violin Colin Jacobsen, violin Nicholas Cords, viola Eric Jacobsen, cello The Knights Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Kim Josephson, baritone Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Jennifer Zetlan, soprano Mary Birnbaum, director Robert Spano, conductor Friday, June =;, =;<?, A:>;pm Talk: The creative team of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) —Jeremy Denk, Steven Stucky, and Mary Birnbaum—in a conversation moderated by Matías Tarnopolsky PLAYBILL FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Cpm Concert: Second Bay Area performance of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Same performers as on Thursday evening. -

Program Notes

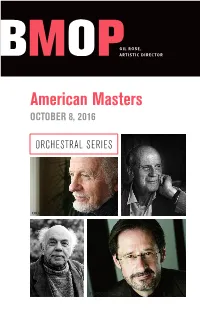

GIL ROSE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ORCHESTRAL SERIES COLGRASS KUBIK SHAPERO STUCKY BMOP2016 | 2017 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY coming up next: The Picture of Dorian Gray friday, november 18 — 8pm IN COLLABORATION WITH ODYSSEY OPERA American Masters “Pleasures secret and subtle, wild joys and wilder sins…” SATURDAY OCTOBER 8, 2016 8:00 BMOP and Odyssey Opera bring to life Lowell Liebermann’s operatic version of Oscar Wilde’s classic horror novel in a semi-staged production. Glass Works saturday, february 18 — 8pm CELEBRATING THE ARTISTRY OF PHILIP GLASS BMOP salutes the influential minimalist pioneer with a performance of his Symphony No. 2 and other works, plus the winner of the annual BMOP-NEC Composition Competition. Boston Accent friday, march 31 — 8pm sunday, april 2 — 3pm [amherst college] Four distinctive composers, Bostonians and ex-Bostonians, represent the richness of our city’s musical life. Featuring David Sanford’s Black Noise; John Harbison’s Double Concerto for violin, cello, and orchestra; Eric Sawyer’s Fantasy Concerto: Concord Conversations, and Ronald Perera’s The Saints. As the Spirit Moves saturday, april 22 — 8pm [sanders theatre] FEATURING THE HARVARD CHORUSES, ANDREW CLARK, DIRECTOR Two profound works from either side of the ocean share common themes of struggle and transcendence: Trevor Weston’s Griot Legacies and Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time. BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT | 781.324.0396 | BMOP.org American Masters SATURDAY OCTOBER 8, 2016 8:00 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY Pre-concert talk by Robert Kirzinger at 7:00 MICHAEL COLGRASS The Schubert Birds (1989) GAIL KUBIK Symphony Concertante (1952) I. -

Composers O – S: 2011-12 Season

REPERTOIRE REPORT COMPOSERS O – S: 2011-12 SEASON Composer Work First Perf. Conductor Orchestra Soloist(s) O'Connor, Mark STRINGS & THREADS Oct. 15, 2011 Anne Harrigan Billings Symphony Orchestra Rosie Weiss, violin and Chorale Offenbach, Jacques ORPHEUS IN THE UNDERWORLD: Oct. 21, 2011 Andrew Constantine Fort Wayne Philharmonic OVERTURE Orchestra Orff, Carl CARMINA BURANA May 17, 2012 Hans Graf Houston Symphony Sherezade Panthaki, soprano Marc Molomot, tenor Hugh Russell, baritone Nov. 11, 2011 Stephen Lancaster Symphony Orchestra unknown unknown, soprano Gunzenhauser Matthew Garrett, tenor Keith Harris, bass-baritone Jan. 20, 2012 Andreas Delfs Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra Norah Amsellem, soprano unknown unknown, tenor Hugh Russell, baritone Milwaukee Symphony Chorus Milwaukee Children's Choir Milwaukee Children's Choir Sep. 29, 2011 Rafael Fruhbeck De National Symphony Orchestra Laura Claycomb, soprano Burgos Nicholas Phan, tenor Hugh Russell, baritone May 31, 2012 Rafael Fruhbeck De The New York Philharmonic unknown unknown, soprano Burgos unknown unknown, baritone unknown unknown, contralto unknown unknown, boy soprano Erin Morley, soprano Nicholas Phan, tenor Mar. 30, 2012 John Nardolilo University of Kentucky unknown unknown, soprano Orchestra unknown unknown, tenor unknown unknown, baritone Ott, David CONCERTO, TWO CELLOS AND Dec. 3, 2011 Mark Russell Smith Quad City Symphony Orchestra Anthony Ross, cello ORCHESTRA Beth Rapier, cello Ott, David SYMPHONY NO. 6 Apr. 13, 2012 Stephen Lancaster Symphony Orchestra Gunzenhauser Pachelbel, Johann CANON Nov. 6, 2011 Gerhardt Zimmermann Canton Symphony Orchestra James Westwater, multi-media Paganini, Niccolo MOSES FANTASY FOR DOUBLE BASS AND Apr. 20, 2012 Martin Majkut Rogue Valley Symphony Gary Karr, double bass ORCHESTRA Page 1 of 21 REPERTOIRE REPORT COMPOSERS O – S: 2011-12 SEASON Composer Work First Perf. -

215236072.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SELECTED PULITZER PRIZE-WINNING COMPOSERS’ CHANGING VIEWS ON COMPOSING FOR WIND BAND A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By TROY BENNEFIELD Norman, Oklahoma 2012 SELECTED PULITZER PRIZE-WINNING COMPOSERS’ CHANGING VIEWS ON COMPOSING FOR WIND BAND A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ___ Dr. William K. Wakefield, Chair ___ Dr. Teresa DeBacker Dr. Lance Drege ____ ___ Dr. Eugene Enrico _ ___ Dr. Frank Riddick © Copyright by TROY BENNEFIELD 2012 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition to the talented composers that gave their time to assist me in this study, there are several individuals without whom this document would not be possible. I would like to thank my committee and especially Dr. Wakefield for his skilled guidance and mentorship through not only this document, but also my entire degree process. I would like to thank the faculty at the University of Oklahoma School of Music, especially Mr. Brian Britt, Dr. Debra Traficante, and their families for their leadership, teaching, and friendship. I am a better person and teacher because of you. Completing this document from my home in Houston would not have been possible without the help of Brian and Erin Wolfe. They are great friends and wonderful people. I owe a great deal of gratitude to the faculty, staff, and students of the University of Houston for supporting me through my first year as a faculty member and allowing me to finish my document while having the pleasure to work with you. -

Bookletdownload Pdf(536

MUSIC21C.BUFFALO.EDU JUNE in BUFFALO JUNE 1-7/2015 th th 40 30Anniversary of Anniversary of David Felder as the founding of Artistic Director June in Buffalo of June in Buffalo JUNE in BUFFALO JUNE 1-7/2015 JUNE IN BUFFALO June 1 – June 7, 2015 David Felder, Artistic Director J.T. Rinker, Managing Director SENIOR FACULTY COMPOSERS: Martin Bresnick David Felder Brian Ferneyhough Bernard Rands Augusta Read Thomas Roger Reynolds Harvey Sollberger Steven Stucky Charles Wuorinen RESIDENT ENSEMBLES: Bu!alo Philharmonic Orchestra Ensemble Signal Meridian Arts Ensemble New York New Music Ensemble Slee Sinfonietta Talujon Percussion Ensemble SPECIAL GUESTS: Irvine Arditti Heather Buck Ethan Herschenfeld Brad Lubman 2 Performance Institute at June in Buffalo May 29-June 7 Eric Heubner, Director PERFORMANCE INSTITUTE FACULTY: Jonathan Golove, Eric Huebner, Tom KolorJean Kopperud, Jon Nelson, Yuki Numata Resnick This year the festival celebrates two landmark anniversaries: the 40th Anniversary of the festival originally founded by Morton Feldman in 1975 and the 30th Anniversary of David Felder as Artistic Director of June in Bu!alo. Presented by the Department of Music and The Robert and Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music, June in Bu!alo is a festival and conference dedicated to composers of the present day. The festival will take place on the campus of the University at Bu!alo from June 1-7, 2015. The week will be filled with an intensive schedule of seminars, lectures, workshops, professional presentations, participant forums, and open rehearsals. Concerts in the afternoons and evenings are open to the general public and critics. -

Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 18, 2012 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ALAN GILBERT AND THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ALAN GILBERT TO CONDUCT NEW YORK PREMIERE OF STEVEN STUCKY’S SYMPHONY VIOLINIST GIL SHAHAM TO PERFORM BARBER’S VIOLIN CONCERTO Program To Conclude with Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances November 29–December 1 Music Director Alan Gilbert, The Yoko Nagae Ceschina Chair, will conduct the New York Philharmonic in the New York Premiere of Symphony, a New York Philharmonic Co- Commission with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Barber’s Violin Concerto, with Gil Shaham as soloist; and Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances Thursday, November 29, 2012, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, November 30 at 2:00 p.m.; and Saturday, December 1 at 8:00 p.m. “I’ve always thought of Steven Stucky as a quintessentially American composer,” said Alan Gilbert. “He is not only one of the most important living composers — he has been an important person in the Philharmonic family, and I am honored to introduce Symphony to New York audiences.” Steven Stucky was the host of the New York Philharmonic’s Hear & Now series from 2005 to 2009. The Orchestra performed the World Premiere of Mr. Stucky’s Rhapsodies (a Philharmonic Co-Commission), led by then-Music Director Lorin Maazel at London’s Royal Albert Hall on the 2008 Tour of Europe, and the U.S. Premiere less than a month later in Avery Fisher Hall. Selections from Mr. Stucky’s Spirit Voices were heard on a Philharmonic Young People’s Concert in 2008, and Alan Gilbert conducted Son et Lumière in February 2012. -

Sibelius Academy Symphony Orchestra and Juilliard Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen , Conductor Jonathan Roozeman , Cello

Tuesday Evening, September 5, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Sibelius Academy Symphony Orchestra and Juilliard Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen , Conductor Jonathan Roozeman , Cello STEVEN STUCKY (1949 –2016) Radical Light ESA-PEKKA SALONEN (b. 1958) Mania JONATHAN ROOZEMAN, Cello Intermission JEAN SIBELIUS (1865 –1957) Lemminkäinen Suite , Op. 22 (“Four Legends from the Kalevala”) Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island Allegro molto moderato Allegro moderato Lemminkäinen in Tuonela Il tempo largamente Molto lento Largo assai The Swan of Tuonela Andante molto sostenuto Lemminkäinen’s Return Allegro con fuoco (poco a poco più energico) Quasi presto Presto Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). The Sibelius Academy Symphony Orchestra tour is supported by the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, the Sibelius Academy Foundation, and Wärtsilä Corporation and is part of the Suomi Finland 100 centenary year events. Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program Steven Stucky also acknowledged Jean Sibelius—whose seventh and fourth sym - by Antti Häyrynen phonies were on the program at the premiere Translation by Daryl Taylor of Radical Light —as another influence on the work: “Sibelius has been a strong influ - Radical Light ence on me for many years, and I espe - STEVEN STUCKY cially admire his Seventh Symphony as an Born November 7, 1949, in Hutchinson, architectural marvel. -

Los Angeles Philharmonic Association Announces 2007/08 Season

Contact: Adam Crane, 213.972.3422, [email protected] Rachelle Roe, 213.972.7310, [email protected] LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC ASSOCIATION ANNOUNCES 2007/08 SEASON Los Angeles (February 13, 2007) – The Los Angeles Philharmonic announces its 2007/08 season: the orchestra’s 89 th since it’s founding, and 16 th under Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen. Marking the orchestra’s fifth season in Walt Disney Concert Hall, concerts run from September 29, 2007 through June 1, 2008. Esa-Pekka Salonen states, “Here it is, our fifth season in Walt Disney Concert Hall. It’s amazing to think about the artistic journey that has brought us to where we are today. The 2007/08 season is distinguished by unexpected musical combinations which emerge throughout the season and exemplify the artistic path that this orchestra continues to forge.” “The 2007/08 programming showcases the Association’s creative and curatorial responsibility as a 21 st century orchestra. This season further solidifies the commitment of Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Philharmonic to bring a broad spectrum of music to our audiences. From Salonen’s exploration of his countryman’s legacy in Sibelius Unbound , to a dynamic look at how cities and music define each other in Concrete Frequency , to showcasing tomorrow’s young musical talent, these three centerpieces converge to demonstrate the bold vision that defines the Los Angeles Philharmonic,” says Philharmonic President Deborah Borda. Sibelius Unbound opens the season. For the first time, Esa-Pekka Salonen surveys Sibelius’ seven symphonies and other orchestral works, which are contextualized by his own Wing on Wing and the world premiere of Steven Stucky’s Radical Light for orchestra, commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. -

Edition 3 | 2019-2020

WHAT’S INSIDE 3...................WELCOME FROM THE MUSIC DIRECTOR 5............WELCOME FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 7....................... WELCOME FROM THE BOARD CHAIR 8-11 ......................ABOUT THE ALBANY SYMPHONY MARCH 14 & 15, 2020: 19................................................ BEETHOVEN EIGHT! APRIL 18, 2020: 29......................................SYMPHONIE FANTASTIQUE MAY 9 & 10, 2020: KEVIN COLE RETURNS: 39............................GERSHWIN IN THE ROARING ‘20s 47........................................CONDUCTOR’S CIRCLE 50-51 ........................................ INDIVIDUAL GIVING 52..................IN HONOR, CELEBRATION, & MEMORY 55................................................ENCORE SOCIETY 57.......................................2019–2020 SPONSORS ALBANY SYMPHONY MUSICIAN 59 ............................................ HOUSING PROGRAM ADVERTISING Onstage Publications Advertising Department 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business, Inc. Contents ©2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. ALBANY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA | 1 2 | ALBANY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA nomination for a recording we made of his music. We will miss him greatly. The program also includes one of the 19th century’s greatest Romantic -

Jean Sibelius | in Tégrale Des Symphonies

Dimanche 4, lundi 5, mardi 6 et jeudi 8 novembre Jean Sibelius | Intégrale des symphonies Los Angeles Philharmonic | Dimanche 4, lundi 5, mardi 6 et jeudi 8 novembre 6 et mardi lundi 5, | Dimanche 4, Esa-Pekka Salonen, direction Intégrale des symphonies des Intégrale Jean Sibelius | Jean Sibelius novembre.indd 1 19/10/07 14:50:07 Sommaire DimaNCHe 4 NoVemBre – 16H (page 5) marDi 6 NoVemBre – 20H (page 7) Sibelius, intégrale des symphonies I Sibelius, intégrale des symphonies III Jean Sibelius Jean Sibelius La Fille de Pohjola, fantaisie symphonique op. 49 Le Retour de Lemminkäinen, Symphonie no 3 en ut majeur op. 52 poème symphonique op. 22 no 4 Symphonie no 1 en mi mineur op. 39 esa-Pekka Salonen Wing on Wing Jean Sibelius Los Angeles Philharmonic Symphonie no 2 en ré majeur op. 43 Esa-Pekka Salonen, direction Los Angeles Philharmonic LUNDi 5 NoVemBre – 20H (page 13) Esa-Pekka Salonen, direction Anu Komsi, soprano Cyndia Sieden, soprano Sibelius, intégrale des symphonies II Jean Sibelius JeUDi 8 NoVemBre – 20H (page 37) Symphonie no 6 en ré mineur op. 104 Sept Chants, op. 17 nos 4 et 6, op. 36 nos 1 et 4, op. 37 nos 3, 4 et 5 (orchestration de John Estacio) Sibelius, intégrale des symphonies IV Symphonie no 5 en mi bémol majeur op. 82 Jean Sibelius Los Angeles Philharmonic Symphonie no 4 en la mineur op. 63 Esa-Pekka Salonen, direction Steven Stucky Ben Heppner, ténor Radical Light (création française) Jean Sibelius Symphonie no 7 en ut majeur op. 105 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen, direction Sibelius novembre.indd 2 19/10/07 14:50:08 Né à Hämeenlinna en Finlande centrale, Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) étudia à Helsinki (1885-1889), Berlin (1889-1890) et Vienne (1890-1891) avant de s’imposer du jour au lendemain dans sa patrie avec sa symphonie-cantate Kullervo (avril 189), inspirée de la mythologie finlandaise du Kalevala. -

Functions of Quotations in Steven Stucky's Oratorio August 4, 1964

FUNCTIONS OF QUOTATIONS IN STEVEN STUCKY‘S ORATORIO AUGUST 4, 1964 AND THEIR PLACEMENTS WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF A QUOTATION CONTINUUM: CULTURAL, COMMENTARY, REMEMBRANCE, AND UNITY Jennifer Tish Davenport, B.M. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2011 APPROVED: David B. Schwarz, Major Professor Stephen Slottow, Committee Member Joseph Klein, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Composition Studies Lynn Eustis, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Davenport, Jennifer Tish. Functions of Quotations in Steven Stucky’s Oratorio August 4, 1964 and Their Placements within the Context of a Quotation Continuum: Cultural, Commentary, Remembrance, and Unity. Master of Music (Music Theory), May 2011, 104 pp., references, 70 titles. The oratorio August 4, 1964 is a twelve-movement work for orchestra, chorus, and four soloists written by Steven Stucky. The premise for the libretto, adapted by Gene Scheer, is the confluence of two events during one day (August 4, 1964) in the life of Lyndon B. Johnson. Although the main idea of the libretto focuses on these two events of this one day, many cultural references of the 1960’s in general can be found as well, such as quotations from the well-known song “We Shall Overcome.” Stucky borrows from a motet he wrote in 2005 for another quotation source utilized in this oratorio, “O Vos Omnes.” My goal in this thesis is to reveal and analyze the many different levels of quotations that exist within August 4, 1964, to explore each quotation's individual function within the oratorio (as a cultural gesture, commentary or remembrance), and to examine the structural coherence that emerges as a result of their use within the oratorio. -

San Francisco Symphony and Esa-Pekka Salonen Announce 2021–22 Season

Contact: Public Relations San Francisco Symphony (415) 503-5474 [email protected] sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / JUNE 29, 2021 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY AND ESA-PEKKA SALONEN ANNOUNCE 2021–22 SEASON HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE: Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen and San Francisco Symphony Collaborative Partners perform and curate programs throughout the season 2021 OPENING WEEK CELEBRATIONS • Esa-Pekka Salonen and Collaborative Partner Esperanza Spalding join with Alonzo King LINES Ballet for Opening Week celebrations including Opening Night Gala and All San Francisco Concert ORCHESTRAL SERIES • Esa-Pekka Salonen leads live and digital projects exploring the music of Igor Stravinsky, including semi-staged performances of Oedipus Rex and Symphony of Psalms directed by Peter Sellars; Orchestral Series performances of The Rite of Spring and Violin Concerto, performed by Leila Josefowicz; and digital-only release of a new staged production of The Soldier’s Tale directed by Netia Jones • Esa-Pekka Salonen leads two weeks of Orchestral Series performances exploring the Greek myth of Prometheus, including Ludwig van Beethoven’s The Creatures of Prometheus, with animations by Hillary Leben; Franz Liszt’s Prometheus; and Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus, The Poem of Fire performed by pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet • Esa-Pekka Salonen conducts the United States premiere of Collaborative Partner Bryce Dessner’s Violin Concerto, performed by Collaborative Partner Pekka Kuusisto • Esa-Pekka Salonen conducts Collaborative Partner Claire Chase