Continuity, the Common Law, and Crisis on Infinite Earths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

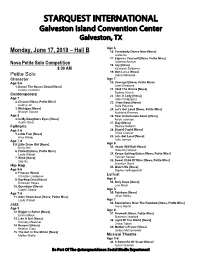

STARQUEST INTERNATIONAL Galveston Island Convention Center Galveston, TX

STARQUEST INTERNATIONAL Galveston Island Convention Center Galveston, TX Age 6 Monday, June 17, 2019 – Hall B 16. Everybody Dance Now [Nova] Lucas Ku 17. Express Yourself [Nova, Petite Miss] Julianna Amaya Nova Petite Solo Competition 18. Joy [Nova] 8:00 AM Ka'miyah Saldierna 19. Ooh La La [Nova] Petite Solo Jaden Norwood Character Age 7 20. Covergirl [Nova, Petite Miss] Age 5-6 1. Dance The House Down [Nova] Juliet Delatorre Charlie Cutchins 21. Hold The Drama [Nova] Sydney Hirsch Contemporary 22. I Am A Lady [Nova] Age 7 Isabel Velazquez 2. Chance [Nova, Petite Miss] 23. I Hate Boys [Nova] Audrey Jin Bella Palacios 3. Michigan [Nova] 24. Let's Get Loud [Nova, Petite Miss] Braelyn Sweed Audriana Ramirez Age 8 26. Poor Unfortunate Souls [Nova] 4. In My Daughters Eyes [Nova] Anlyn Johnson Austin Steel 27. Slay [Nova] Folkloric Steelye Roberts 28. Stupid Cupid [Nova] Age 5-6 5. Little Fish [Nova] Chloe Chenier Amy Wang 29. Lets Get Loud [Nova] Julia Jarmon Age 7-8 5.5 Little Drum Girl [Nova] Age 8 30. Heads Will Roll [Nova] Emily Mei 6. Fireball [Nova, Petite Miss] Makenna Wasek 31. Keeps Getting Better [Nova, Petite Miss] Layla Waladi 7. Wind [Nova] Tallulah Seuser Qiqi Su 32. Sweet Child Of Mine [Nova, Petite Miss] Brooklyn Davis Hip Hop 33. Watch Me [Nova] Age 5-6 Sophie Hollingsworth 8. Finesse [Nova] Christian Cardenas Lyrical 9. Hip -Hop Diva [Nova] Age 8 34. Only Hope [Nova] Emerson Hayes 10. Questions [Nova] Lexi Mauk Caden Chang Age 6 35. Rainbow [Nova] Age 7-8 11. -

Red Lanterns: Forged in Blood (The New 52) Vol 6 PDF Book

RED LANTERNS: FORGED IN BLOOD (THE NEW 52) VOL 6 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. Califore,Charles Soule | 160 pages | 11 Aug 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401254841 | English | United States Red Lanterns: Forged in Blood (the New 52) Vol 6 PDF Book Issue 3-REP. Retrieved — via Twitter. Charles Soule departed this title early as p I'm going to get a stamp made up with all the reasons why DC are awful at collecting multi-series crossovers, so I don't have to repeat myself in every review. Parts of Godhead with no resolution. In this volume we explore the idea of anger and its purpose. He get into a fight with what appears to be some random bad guy, which lead into a crossover with the New Gods. However, it appears that a new rage entity has since been born from the excess rage left on Earth from the war with Atrocitus. More for completists than new Green Lantern fans. The passage taken from The Book of the Black at the end of Blackest Night 3 states that rage will be the second emotion to fall in the Black Lantern Corps' crusade against the colored lights. November — May The artistry and the writing is still awesome; however, almost halfway through it the storyline just immediately took a right turn and changed to years after a certain section. Beautifully drawn and passionately written, this book is a must-have for not just Lantern fans, but any fan of comics. The Butcher was eventually freed from Krona's control after Hal Jordan defeated and killed the rogue Guardian. -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Earth-11 Jumpchain Yes, This Is Just for Waifus

Earth-11 Jumpchain Yes, this is just for waifus This is a world of superhumans and aliens, one that may seem very familiar at first. However, this isn’t the normal world of DC Comics. No, this is one of its parallel dimensions, one where everybody is an opposite-gender reflection of their mainline counterparts. It’s largely the same besides that one difference, so the events that happened in the primary universe are likely to have happened here as well. The battle between good and evil continues on as it always does, on Earth, in space, and in other dimensions. Superwoman, Batwoman, Wonder Man, and the rest of the Justice League fight to protect the Earth from both from it’s own internal crime and corruption and from extraterrestrial threats. The Guardians of the Universe head the Green Lantern Corps to police the 3800 sectors of outer space, of which Kylie Rayner is one of the premier members. On New Genesis and Apokolips in the Fourth World, Highmother and Darkseid, the Black Queen vie for power, never quite breaking from their ancient stalemate. You receive 1000 CP to make your place in this world. You can purchase special abilities, equipment, superpowers, and friends to help you out on your adventures. Continuity You can start at any date within your chosen continuity. Golden Age The original timeline, beginning in 1938 with the first adventure of Superwoman. Before long she was joined by Batwoman, Wonder Man, and the Justice Society of America. The JSA is the primary superhero team of this Earth, comprised of the Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkwoman, Dr. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Superman Or Batman Cakes

2105-8507SMnBatWebIs50530.qxd 7/12/05 11:42 AM Page 1 Instructions for To Decorate Superman Cake To make the Superman cake in the colors shown you will need Wilton Baking & Decorating Icing Colors in Royal Blue, Christmas Red, Copper (skin tone), and Lemon Yellow, tips 3, 16 and 18. We suggest that you tint all icing at Superman or Batman one time while cake cools. Refrigerate tinted icings in covered containers until ready to use. Cakes Make 3 cups buttercream icing: 1 PLEASE READ THROUGH INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE YOU BEGIN. • Tint 1 ⁄2 cups blue 3 IN ADDITION, to decorate cakes you will need: • Tint ⁄4 cup red • Tint 1⁄4 cup copper (skin tone) • Wilton Decorating Bag and Coupler or • Tint 1⁄4 cup yellow parchment paper triangles • Reserve 1⁄4 cup white • Tips 3, 16, and 18 • Wilton Icing Colors in Royal Blue, WITH RED ICING WITH YELLOW ICING • Use tip 3 and “To Outline” • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” Christmas Red, Copper (skin tone), directions to outline details on cape directions to cover belt Lemon Yellow and Black • Use tip 18 and “To Make Stars” • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” • Serving plate directions to cover cape directions to squeeze out a second • One 2-layer cake mix or ingredients for layer of stars in a circle to give the your favorite layer cake recipe WITH BLUE ICING appearance of a belt buckle • 3 cups buttercream icing (recipe) or • Use tip 3 and “To Outline” directions to outline details on suit WITH RED ICING 2 packages of creamy vanilla type • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” frosting mix (15.4 oz. -

X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Free

FREE X-MEN EPIC COLLECTION: CHILDREN OF THE ATOM PDF Stan Lee,Jack Kirby | 520 pages | 31 Dec 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785189046 | English | New York, United States X-Men Epic Collection: Children Of The Atom - Comics by comiXology Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. X-Men Epic Collection Vol. Jack Kirby. Now, in this massive Epic Collection, you can feast your eyes as Stan, Jack and co. You'll experience the beginning of Professor X's teen team and their mission for peace and brotherhood between man Billed as "The Strangest Super-Heroes of All! You'll experience the beginning of Professor X's teen team and their mission for peace and brotherhood between man and mutant; their first battle with arch-foe Magneto; the dynamic debuts of Juggernaut, the Sentinels, Quicksilver, the Scarlet X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom and X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jun 27, Sean Gibson rated it really liked it. And, I love me X-Men Epic Collection: Children of the Atom Stan Lee—the guy is one of my real-life heroes, and Spider-Man is my all- time favorite superhero. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Planets: Earth, Mars, & Beyond

From Atom to Universe Planets: Earth, Mars, & Beyond Research Planetary Science Dr. Christopher Adcock Assistant Research Professor Department of Geoscience Email: [email protected] Expertise: Planetary Surface Processes | Extraterrestrial Habitability Planetary Surface Processes / Low Temperature Geochemistry: Mars Left: Synthesized chlorapatite (top) and whitlockite used in experiments. Same scale for both images. The ability to synthesize these Mars- relevant minerals in quantity is a specialty of Dr. Adcock and the Hausrath LaB. Physical sample allow for experiments that cannot Be done By calculation. Above: Empirical Dissolution rates Left: Shock induced of terrestrial (fluorapatite / metamorphism of whitlockite (a) whitlockite) and more Mars- to merrillite/whitlockite mix (B). relevant phosphate minerals Shock removes the water from (chlorapatite and merrillite). 25 °C , whitlockite to make merrillite. variaBle pH. Higher rates mean Since all of our current samples potentially higher phosphate of Mars come from shocked availaBility in past Martian meteorites, this has implications environments – with positive for the past hydrologic cycle of implications for past life. Adcock et Mars. Adcock et al., (2017) al., (2013) Nature Geoscience 6 Nature communications 8 (1), 1- (10), 824-827. 8. Extraterrestrial Habitability | In Situ Resources and Environments on Mars Left: Results of low temperature hydrogen generation experiments using Martian soil simulants. These experiments show it is possible to use Martian materials and a low energy system to generate Above: A typical set of hydrogen generation experiments. H2 for fuel, energy, or water for future human missions to Simulants and soution are slowly Mars. Adcock et al., (2020), shaken at 25 °C to produce 51st LPSC. hydrogen. -

Comics Original Graphic Novels Collected Editions

Store info: FILL OUT THIS INTERACTIVE CHECKLIST AND RETURN TO YOUR RETAILER TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS THE LATEST FROM DC! (Tuesday availability at participating stores) TO VIEW CATALOG, VISIT: DCCOMICS.COM/CONNECT COMICS M V M = Main V = Variant M V M = Main V = Variant Check with your retailer for variant cover details. Check with your retailer for variant cover details. Available Tuesday, November 3, 2020 _ _ Detective Comics #1031 _ _ Batman #102 _ _ The Flash #766 _ _ Batman: The Adventures Continue #6 _ John Constantine: Hellblazer #12 _ _ DC Classics: The Batman Adventures #6 _ Justice League Dark #28 _ _ DCeased: Dead Planet #5 _ The Last God #10 MOVIE HOMAGE VARIANT _ _ Legion of Super-Heroes #11 _ _ The Dreaming: Waking Hours #4 _ _ The Other History of the DC Universe #1 _ _ Hellblazer: Rise and Fall #2 _ _ Red Hood #51 _ _ Justice League #56 _ _ Suicide Squad #11 _ _ Strange Adventures Director’s Cut #1 _ _ Wonder Woman #767 _ _ Sweet Tooth: The Return #1 _ _ Tales from the Dark Multiverse: Batman: Hush #1 ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVELS _ _ Young Justice #20 Available Tuesday, January 5, 2021 Available Tuesday, November 10, 2020 _ House of El Book One: The Shadow Threat TP _ _ American Vampire 1976 #2 Available Tuesday, January 12, 2021 _ _ The Batman’s Grave #12 _ We Found a Monster TP _ _ Dark Nights: Death Metal Infinite Hour Exxxtreme! #1 _ _ Detective Comics #1030 COLLECTED EDITIONS _ _ The Flash #765 _ _ The Green Lantern Season Two #9 Available Tuesday, December 1, 2020 _ _ Hawkman #29 _ The Green Lantern Season Two Vol. -

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions Committee: Adam Z. Newton, Co-Supervisor John M. Slatin, Co-Supervisor Brian A. Bremen David J. Phillips Clay Spinuzzi Margaret A. Syverson Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions by Jason Todd Craft, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication For my family Acknowledgements Many thanks to my dissertation supervisors, Dr. Adam Zachary Newton and Dr. John Slatin; to Dr. Margaret Syverson, who has supported this work from its earliest stages; and, to Dr. Brian Bremen, Dr. David Phillips, and Dr. Clay Spinuzzi, all of whom have actively engaged with this dissertation in progress, and have given me immensely helpful feedback. This dissertation has benefited from the attention and feedback of many generous readers, including David Barndollar, Victoria Davis, Aimee Kendall, Eric Lupfer, and Doug Norman. Thanks also to Ben Armintor, Kari Banta, Sarah Paetsch, Michael Smith, Kevin Thomas, Matthew Tucker and many others for productive conversations about branding and marketing, comics universes, popular entertainment, and persistent world gaming. Some of my most useful, and most entertaining, discussions about the subject matter in this dissertation have been with my brother, Adam Craft. I also want to thank my parents, Donna Cox and John Craft, and my partner, Michael Craigue, for their help and support.