PDF 654.11 Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kim Possible – Sie Kann Alles«

PROGRAMM 20/2007/2 11 »Kim Possible – sie kann alles« Ein Gespräch mit Robert Schooley und Mark McCorkle* Die Mitglieder von Team Possible und jetzt ist das tatsächlich im All- tion zu arbeiten. Wenn jemand Kim – sind das Helden? tag der Kinder angekommen. über ihre Website kontaktiert, dann Es sind Helden, aber wir wollten sie hilft sie. nicht zu Superhelden machen, d. h. Welche Rolle spielt Humor in der sie sind nicht unzerstörbar oder etwas Serie? Wie haben Sie die Figur Kim in der Art. Wir wollten, dass Kinder Kim Possible ist ja in erster Linie eine Possible entwickelt? sich in Kim und Ron wiederfinden Comedy-Serie. Die Serie parodiert Wir bekamen die Anfrage von den können. Was Kim macht, ist ziemlich viele der Konventionen von James- Leuten von Disney Channel, die eine fantastisch und unglaublich, aber Bond-Filmen und anderen Filmen neue Serie mit normalen Kindern in trotzdem muss sie sich mit Teenager- dieses Genres. Wir haben die Erfah- außergewöhnlichen Situationen woll- Problemen herumschlagen. Das war rung gemacht, dass Jungen Action ten. Bob und ich waren auf dem Weg es auch, was Disney Channel interes- mögen, auch wenn’s reine Action ist; zurück vom Mittagessen, und da habe sierte: normale Kinder in außerge- Mädchen wollen eher Persönlichkei- ich mich zu ihm umgedreht und ge- wöhnlichen Situationen. Also haben ten sehen und Beziehungen. Was sagt: »Kim Possible, sie kann alles.« wir ganz zu Anfang beschlossen: Kim Mädchen und Jungen vereint, ist, Und dann sagte Bob: »Ron Stopp- ist ein normales Mäd- dass sie gern lachen, able. Er nicht.« Und damit hatten wir chen, aber das, was sie und deswegen wollten praktisch schon das ganze Konzept. -

Kim Possible

FORSCHUNGSPAPIERE KINDER- UND JUGENDMEDIEN Forschungspapiere des Masterstudiengangs Kinder- und Jugendmedien der Universität Erfurt 4/2010 Kim Possible - Eine inhaltsanalytische Studie Tina Becherer Universität Erfurt | Masterstudiengang Kinder– und Jugendmedien Impressum Forschungspapiere Kinder- und Jugendmedien Herausgeber: Dr. Sandra Fleischer Dr. Sven Jöckel Kathleen Arendt Robert Seifet Universität Erfurt Masterstudiengang "Kinder- und Jugendmedien" Nordhäuser Straße 63 99089 Erfurt urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201000745 © bei den Autoren 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ............................................................................................................. 4 2 Methode ................................................................................................................ 5 3 Ergebnisse ............................................................................................................. 7 4 Diskussion ........................................................................................................... 13 5 Literatur .............................................................................................................. 15 6 Appendix ............................................................................................................. 16 Einleitung 1 Einleitung Ein kurzer Blick ins Fernsehprogramm für Kinder genügt um zu sehen, dass männliche Hauptfiguren in Zeichentrickserien für jedes Alter dominieren im Vergleich zu weiblichen Hauptfiguren. Demzufolge werden Jungen auf ihrer Suche -

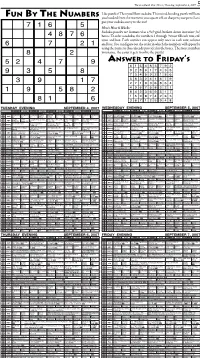

Answer to Friday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, September 4, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRIDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING SEPTEMBER 4, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING SEPTEMBER 5, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone CSI: Miami: Death Pool CSI: Miami: If Looks Could The Sopranos: Two Two Coreys Two Coreys CSI: Miami: Death Pool Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bnty Mindfreak Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel Dog Bounty Dog Bounty 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E (R) (R) (R) (TVPG) (TVPG) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) 100 (TV14) (HD) Kill (TV14) (HD) Tonys (TVMA) (HD) (R) (R) 100 (TV14) (HD) According According NASCAR in Primetime Primetime: The Outsiders KAKE News Nightline (:01) Jimmy Kimmel Live Laughs Just for i-Caught Amateur video. -

Notes to Santa Sophia Maymudes

Notes to Santa Sophia Maymudes ACROSS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1. Pigeon-loving Muppet 5. TV screen type (abbr.) 14 15 16 8. Guarantee 14. 604 square miles, for Cape Cod Bay 17 18 19 15. You can make one by going all the way 20 21 around a rotary 16. Music legend Tina 22 23 24 25 26 27 17. Travel around 18. Keys that can help you 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 get from here to there 20. *** What Gayla Peevey 35 36 37 38 wants for Christmas 22. Massachusetts : Bay 39 40 41 42 State:: Rhode Island : ____ State 23. Precursor to "two, 43 44 three, four" in a march 24. Lead 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 28. Feature of a puppy's paw 52 53 54 55 56 57 29. 5pm, in memo lingo 32. Caviar, e.g. 58 59 60 61 34. *** What Mariah Carey wants for Christmas 62 63 64 65 35. In the midst of a hot streak 37. Certain foam balls 66 67 68 39. *** What Spike Jones and his City Slickers 69 70 71 want for Christmas 43. Muscle-y © 2020 44. Wrap up, as earbuds 69. Owner of ESPN 12. With 11-Down, 42. Male turkey 45. "He's _____ That" 70. Grp. whose seal is an historic Provincetown 47. Poitier with a (gender-flipped eagle holding a key lodging Presidential Medal of remake) 71. Good things to know 13. "The Marvelous _____ Freedom 46. Key on the top left of at the poker table Maisel" 49. -

TAG21 Mag Q1 Web2.Pdf

IATSE LOCAL 839 MAGAZINE SPRING 2021 ISSUE NO. 13 THE ANIMATION GUILD QUARTERLY GIMMIE SHELTER: CREATING CAPTIVATING SPACES IN ANIMATION GIMME SHELTER SPRING 2021 CREATING CAPTIVATING SPACES IN ANIMATION FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION BEST ANIMATED FEATURE GLEN KEANE, GENNIE RIM, p.g.a., PEILIN CHOU, p.g.a. GOLDEN GLOBE ® NOMINEE BEST ANIMATED FEATURE “ONE OF THE MOST GORGEOUS ANIMATED FILMS EVER MADE.” “UNLIKE ANYTHING AUDIENCES HAVE SEEN BEFORE.” “★★★★ VIBRANT AND HEARTFELT.” FROM OSCAR®WINNING FILMMAKER AND ANIMATOR GLEN KEANE FILM.NETFLIXAWARDS.COM KEYFRAME QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE ANIMATION GUILD, COVER 2 NETFLIX: OVER THE MOON PUB DATE: 02/25/21 TRIM: 8.5” X 10.875” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.125” ISSUE 13 CONTENTS 46 11 AFTER HOURS 18 THE LOCAL FRAME X FRAME Jeremy Spears’ passion TAG committees’ FEATURES for woodworking collective power 22 GIMME SHELTER 4 FROM THE 14 THE CLIMB 20 DIALOGUE After a year of sheltering at home, we’re PRESIDENT Elizabeth Ito’s Looking back on persistent journey the Annie Awards all eager to spend time elsewhere. Why not use your imagination to escape into 7 EDITOR’S an animation home? From Kim Possible’s NOTE 16 FRAME X FRAME 44 TRIBUTE midcentury ambience to Kung Fu Panda’s Bob Scott’s pursuit of Honoring those regal mood, these abodes show that some the perfect comic strip who have passed of animation’s finest are also talented 9 ART & CRAFT architects and interior designers too. The quiet painting of Grace “Grey” Chen 46 SHORT STORY Taylor Meacham’s 30 RAYA OF LIGHT To: Gerard As production on Raya and the Last Dragon evolved, so did the movie’s themes of trust and distrust. -

A Deconstruction and Qualitative Analysis of the Consumption of Traditional Entertainment Media by Elementary-Aged Children Diag

A DECONSTRUCTION AND QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE CONSUMPTION OF TRADITIONAL ENTERTAINMENT MEDIA BY ELEMENTARY-AGED CHILDREN DIAGNOSED WITH EMOTIONAL DISORDERS John Lloyd Lowdermilk III, B.S., M.S., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2004 APPROVED: Lyndal M. Bullock, Major Professor Alan B. Albarran, Minor Professor Ron Fritch, Committee Member Bertina Combes, Committee Member and Graduate Coordinator of Special Education Jon Young, Chair of the Department of Technology and Cognition M. Jean Kellar, Dean of the College of Education Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lowdermilk, John Lloyd, III, A deconstruction and qualitative analysis of the consumption of traditional entertainment media by elementary-aged children diagnosed with emotional disorders, Doctor of Philosophy (Special Education), August 2004, 116 pp., 3 tables, 86 titles. This qualitative study examined whether a connection exists between children with emotional disorders consumption of traditional entertainment media and their subsequent vegative/anti-social classroom behavior. Research participants included six first-grade children diagnosed with an emotional disorder and their teacher. They were interviewed using a semi- structured approach. The students were observed in the natural setting of their classroom for a total of twenty-four hours, over a four-day period. Transcripts and classroom observations were analyzed, looking for connections between behavior and consumption of traditional entertainment media. Findings from this study concluded that these students used traditional entertainment media as a method of temporally escaping from the environment of their respective households. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................. iv LIST OF TABLES.............................................. -

Crime-Fighting Kim Gets in the Game

Gifts Get Personal Survey: Getting Financial Advice Pays Off (NAPSA)—If you want to give a present worth remembering, make Jazzing Up Traditional Holiday Baking Favorites (NAPSA)—According to a recent your gift as personal as possible. (NAPSA)—It is the time of survey, nearly 84 percent of Ameri- That’s the advice from gift- cans believe they are in either excel- year for holiday baking—the giving gurus who say it’s smart time of year when friends and lent or okay “financial fitness” to take a few minutes to consider shape. Eleven percent believe they family gather in the kitchen to the personalities on your gift share recipes, treats and laugh- are in troublesome shape. Yet when list, before you shop. asked if and how they seek financial ter. Whether painting smiles on For instance, if you’ve got a freshly baked gingerbread men assistance, 67 percent of consumers foodie in your life, he might appre- had never received advice on their or enjoying cocoa and cookies, ciate something as simple as families gather around the personal finances; only 31 percent being taken to dinner, while a gar- had sought advice. kitchen table to share their holi- dener might love some new tools day traditions and treats. Overall results of the survey, or a book about seeds. Candy Cane Kisses add a splash conducted on behalf of the Finan- You can create some taste- of seasonal color and a twist to a cial Services Roundtable—repre- tempting new traditions this holi- traditional cookie favorite. senting 100 of the largest inte- day with easy variations on 1 grated financial services companies favorite family recipes. -

JUMP WISH-LIST Rules/Notes: Settings

JUMP WISH-LIST Rules/Notes: ● This list is solely for settings that don’t have jumps made yet. ● No jumps you want to see redone, I’m not going to go down this path. If there is any such setting mentioned on list, then as soon as it is pointed out to me, I’ll remove it. ● Settings already claimed will be either removed from list or have claim noted. I’ll accept info about claims only from the jump-maker who claimed it. ● I hope to maintain this list in such way that /tg/, SB and QQ communities can all check it out. If you don’t like something on it, just ignore it. After all, if jump is being made doesn’t mean you have to use it. Furthermore, we all have different tastes, be mindful of that. ● Fanfics will be listed separately. Some people like the idea of such jumps, some don’t. I might end up removing this section altogether just because it is so difficult to decide if certain fanfic would be acceptable for being turned into jump or not. ● Settings will be listed alphabetically within a genre, by their official name. Any other names will be included after that one. Please include genre and medium with any suggestions (e.g. KultHorror - Tabletop RPG; The Culture - Science Fiction - Novel) ● Rule of thumb – recommend settings that you would want to visit in order to interact with characters and storylines, not in order to get specific perks/powers/items. Settings: 0-9 ● 100, The (SF - TV Series) ● 300 (movies) ● 3x3 Eyes (manga) ● 7th Heaven (TV series) ● 9 (movie) ● 100 Bullets (vertigo) ● 11eyes (VN/anime) ● 2 Broke Girls (TV Series) -

KATHLEEN DETORO Costume Designer

KATHLEEN DETORO Costume Designer official website TELEVISION (partial list) CASTLE ROCK (Season 2) Bad Robot / Hulu EP: J.J. Abrams, Stephen King Trailer COUNCIL OF DADS (Pilot) NBC EP: Joan Rater, Tony Phelan THE CROSSING (Season 1) ABC Studios Dir: Rob Bowman SCALPED (Pilot) WGN / Warner Horizon Dir: Adil El Arbi, Bilall Fallah Prod: Len Goldstein TRAINING DAY (Pilot) CBS Prod: Antoine Fuqua, Jerry Bruckheimer, Trailer Will Beall BLOOD & OIL (Season 1) Flame Ventures / ABC Prod: Josh Pate, Cynthia Cidre, Tony Krantz VEGAS (Pilot & Season 1) CBS Studios / CBS Prod: Nick Pileggi, James Mangold, Cathy Konrad BREAKING BAD (Pilot & Seasons 1-4) Sony / AMC Prod: Vince Gilligan, Mark Johnson Clip IDENTITY (Pilot) CBS Studios / CW Exec Prod: Alex Kurtzman, Roberto Orci NECESSARY ROUGHNESS (Pilot) Sony / USA Prod: Elizabeth Kruger, Craig Shapiro FLASH FORWARD (Pilot) ABC Studios / ABC Prod: Brannon Braga, David Goyer MASTERWORK (Pilot) 20th Century Fox / FOX Prod: Paul Scheuring, Zack Estrin JUSTICE (Pilot & Season 1) Warner Bros. / FOX Prod: Jerry Bruckehimer THRESHOLD (Season 1) CBS Paramount / CBS Prod: Brannon Braga, David Heyman CLOSE TO HOME (Pilot) Warner Bros. / CBS Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer SKIN (Pilot & Season 1) Warner Bros. / FOX Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer LEGALLY BLONDE (Pilot) Touchstone TV / ABC Prod: Marc Platt, Rachel Sweet *ALLY MCBEAL (Seasons 4 & 5) 20th Century Fox / FOX Prod: David E. Kelley, Bill D’Eli *Costume Designer’s Guild Nomination 2001 & 2003 FEATURES (partial list) KIM POSSIBLE Disney Prod: Zanne Devine, Dir: Zach Lipovsky, Robert Schooley Adam Stein THE GUEST Snoot Entertainment Prod: Keith Calder, Dir: Adam Wingard Jessica Wu, Chris Harding SCREAM II Dimension Prod: Bob Weinstein, Dir: Wes Craven Cathy Konrad HARD RAIN Paramount Pictures Prod: Mark Gordon, Dir: Mikael Salomon Ian Bryce DEAD MAN ON CAMPUS Paramount/MTV Films Prod: Gale Ann Hurd Dir: Alan Cohn OVERNIGHT DELIVERY New Line Cinema Prod: Roger Birnbaum Dir: Jason Bloom . -

Los Héroes De TV Preferidos

New Children’s favourite TV heroes Which TV heroes top German girls’ and boys’ lists right now? The International Central Institute for Youth and Educational Television at Bavarian Broadcasting Station questioned 716 randomly selected children aged 6 to 12¹ concerning their current favourite television characters. Through qualitative interviews with a further 300+ children we explored the reasons for their enthusiasm. Children’s favourite TV characters in Germany (6-12 years) Boys Girls SpongeBob (18%) Hannah Montana (28%) Ben 10 (9%) Barbie (7%) Bart Simpson (6%) Kim Possible (5%) Batman (5%) Bob Esponja (4%) Bob the Builder (4%) Bibi Blocksberg (3%) Homer Simpson (3%) Princess Lillifee (2%) Source: IZI, 4th quarter 2010; Basis: n = 716 children aged 6-12, rep. random sample Girls: a search for ideals, accompanied by a desire to rediscover themselves. Among girls, Hannah Montana is the most popular television character by a large margin. They enjoy the comedy, but also say she portrays their emotional life particularly well. They recognise themselves in Miley’s problems and struggles, and enjoy it all the more because she manages to keep cool. Miley (and to an even greater degree Hannah) thereby reflects adolescent girls’ wish- fulfilment fantasies and symbolises typical tween identity development. Girls simultaneously regard themselves as remarkably competent like Hannah – for example, in certain school subjects – while also concentrating on their deficiencies and regarding themselves as something of a Miley. Because Miley is somewhat older than the girls themselves, she can become their ideal friend or fantasy sister. The enormous range of licensed “Hannah Montana” merchandise in Germany helps keeping her to be the focus of attention and a cultural trend for girls. -

Comedic Action-Adventure Movie Kim Possible Premieres Saturday, February 16 on Disney Channel Canada

COMEDIC ACTION-ADVENTURE MOVIE KIM POSSIBLE PREMIERES SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 16 ON DISNEY CHANNEL CANADA A First Look at Turbocharged Miniseries Fast Layne to Follow the Next Day For images visit the Corus Media Centre To share this release socially use: http://bit.ly/2SEzDzg Fast Layne Photo Credit: Disney Channel/Ed Herrera* Kim Possible Photo Credit: Disney Channel For Immediate Release TORONTO, December 10, 2018 – Kim Possible, a Disney Channel Original Movie based on the beloved animated series, will premiere Saturday, February 16 at 7 p.m. ET/PT, on Disney Channel Canada. In this comedic action-adventure movie, a live-action transformation of the original animated series, newcomer Sadie Stanley stars as the iconic teen hero Kim Possible along with Sean Giambrone (The Goldbergs) as her best friend and sidekick, Ron Stoppable. The following day, Disney Channel Canada will present a first look at the new eight-part miniseries Fast Layne with back-to-back episodes at 7:30 p.m. ET/PT and 8 p.m. ET/PT on Sunday, February 17. Kim Possible begins as Kim and her best friend and sidekick, Ron Stoppable, start Middleton High School where Kim must navigate an intimidating new social hierarchy. She is ready to tackle the challenge head- on, just as she has with everything else in life, but her confidence is shaken when she faces roadblocks at every turn – getting lost in the confusing hallways, being late to class and facing rejection during soccer tryouts from her frenemy, Bonnie. Kim's day starts to turn around when she and Ron meet and befriend Athena, a new classmate and Kim Possible superfan who is having an even worse day than Kim. -

2003-Annual-Report.Pdf

The Company 2003 ANNUAL REPORT CELEBRATING 75 YEARS OF MICKEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 1 LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS 2 FINANCIAL REVIEW 10 COMPANY OVERVIEW 14 STUDIO ENTERTAINMENT 16 PARKS AND RESORTS 24 CONSUMER PRODUCTS 32 MEDIA NETWORKS 36 WALT DISNEY INTERNATIONAL 50 DISNEYHAND 51 ENVIRONMENTALITY 52 FINANCIAL SECTION 53 REPORT OF INDEPENDENT AUDITORS 95 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (In millions, except per share data) 2003 2002 Revenues $27,061 $25,329 Segment operating income 3,174 2,822 Diluted earnings per share before the cumulative effect of accounting changes 0.65 0.60 Cash flow provided by operations 2,901 2,286 Borrowings Total 13,100 14,130 Net(1) 11,517 12,891 Shareholders’ equity 23,791 23,445 (1) Net borrowings represent total borrowings of $13,100 million less cash and cash equivalents of $1,583 million. 1#1 LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS To Fellow Owners and Cast Members: I’ve always believed that good news shouldn’t wait, so this year I thought I’d start right off with a review of the numbers. In 2003, we experienced solid earnings growth despite the difficult economic and geopolitical environment that prevailed during most of the year. Most significantly, our fourth quarter was very strong, with more than double the earnings of Q4 in 2002, underscoring our confidence in generating growth in the new year. Equally important, we delivered free cash flow for the year that was up more than 50 percent over last year and continued to bolster our balance sheet. During fiscal 2003, our stock price appreciated 36 percent, compared to the S&P 500’s growth of 25 percent.