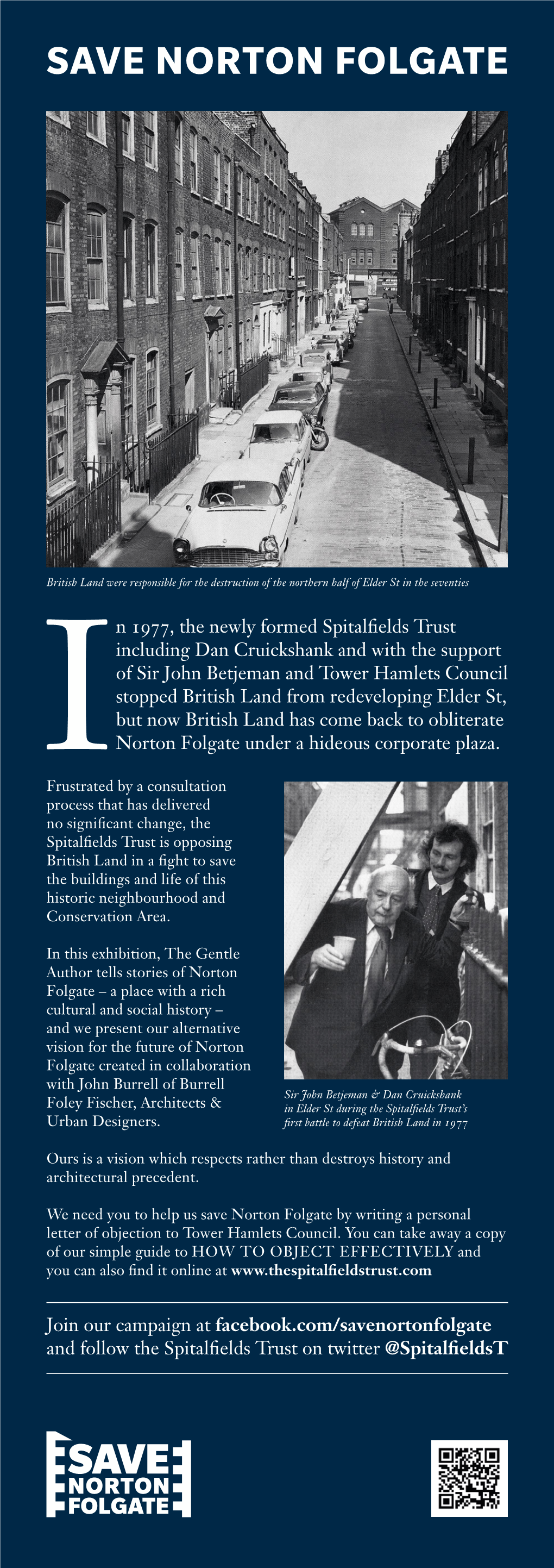

Save Norton Folgate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

J103917 Principal Place Broch

THE SHARD THE CITY CORE LIVERPOOL SPITALFIELDS STREET STATION 01 Introduction WELCOME TO THE WEST SIDE On the border of the fast-paced hub of the City and the creative buzz of Shoreditch, Principal Place, a vibrant mixed-use development by Brookfield, is perfectly placed to enjoy the rich variety of opportunities offered by this thriving business location. Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, has already chosen it as their new home, taking 518,000 sq ft. Now The West Side, Principal Place, with its own dramatic entrance and atrium, offers a further 81,000 sq ft of prime office accommodation and the chance to join an illustrious commercial neighbourhood. — HELLO _THE WEST SIDE CGI of the Piazza at Principal Place Local Area 04 ISLINGTON N TREET OLD S S FLOWER H O MARKET R E D I T C H H I OLD G H STREET ET S TRE T OLD S R E E G T RE BETHNAL GREEN RD AT E AS PRIME POSITION TE R N ST Between the solid tradition of the RE B ET SCLATER ST R I C Bank of England and the innovating SHOREDITCH K C L I D A T HIGH STREET A N Y O technologies of Silicon Roundabout, E R R N I O A E T A T The West Side at Principal Place R D U A C G L C offers the best of all worlds. O O F M WEST SIDE N M O E T R Shoreditch is transforming on an R C O IA N L S almost weekly basis, as Michelin- T R E E T starred restaurants, cool clubs, visionary galleries and high-end CH brands set up shop alongside the ISWELL ST area’s historic markets and long D A O R established East End businesses. -

Bishopsgate Court, 4-12 Norton Folgate, Liverpool St., London E1

Public Transport Our Liverpool Street venue is conveniently located in the City. Situated just 5 minutes from both Liverpool Street Station and Shoreditch High Street overground station, the venue is easy to reach from a number of train, underground and bus routes. By underground from Liverpool Street Central Line, Circle Line, Hammersmith & City Line or Metropolitan Line. For exits from all underground lines, follow signs for Liverpool Street mainline station. Once on the main concourse of the mainline station, head for Way Out 1 (Bishopsgate West), located next to Platform 14. Liverpool Street Take the escalator or stairs up to street level and as you leave the station, Bishopsgate Court, 4-12 Norton Folgate, London E1 6DQ turn left onto Bishopsgate and cross the road. After 500 yards as the road becomes “Norton Folgate”, you will cross a small road called Spital Tel: 020 7763 6800 Fax: 020 7763 6801 Square. Bishopsgate Court is the 2nd building on your right (the red brick building opposite the tall glass building). etc.venues Liverpool Street is Email : [email protected] POUIFSEnPPS By train from Liverpool Street Follow directions as above from the main concourse. ) $ " 5 By overground train from Shoreditch High Street * 8 % 0 3 4 & Turn left out of Shoreditch Overground Station and then left onto Bethnal ) * 1 5 3 4 5 4 5 Green Road following signs to Shoreditch High Street. Once you reach 0 4 ) BISHOPSGATE COURT . $ Shoreditch High Street turn left and after 200yds the venue will be on the 4 4-12 NORTON-FOLGATE 0 0 . -

1469.6.1 Blossom Street Heritage Assessment R2

Blossom Street Appendix J – Built Heritage Replacement Environmental Statement Volume III Blossom Street Appendix J1 – Heritage Assessment Environmental Statement Volume III Blossom Street, E1: Heritage Assessment Volume 1 Blossom Street, E1 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................... 4 The site ......................................................................................... 4 Heritage Assessment The Existing Building Heritage Analysis ........................................... 4 Contributors ................................................................................. 4 2 The site and its development ..................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................. 7 The history of the site .................................................................... 7 Overview ...................................................................................... 7 Summary ................................................................................... 24 The buildings of the Blossom Street site ...................................... 26 Nos. 13-20 Norton Folgate and nos. 1-2 Shoreditch High Street ... 26 No. 13 Norton Folgate ................................................................ 27 No. 14 Norton Folgate ................................................................ 27 No. 15 Norton Folgate ................................................................ 28 Nos. 16-19 Norton -

7.0 Plot S1/S1c

7.0 Plot S1/S1c 7.1 Introduction 7.2 Existing Buildings 7. 3 Evolving the Design 7.4 Proposed Scheme 7.4.1 Land Use 7.4.2 Amount of Development Proposed 7.4.3 Layout - Floor Plans 7.4.4 Scale / Appearance 7.6 Inclusive Design 7.5 Landscape 7.0 Plot S1/S1c 7.1 Introduction Plots S1/S1c and S1a and S1b form part of Site S1. Site S1 is the largest plot and is a coherent urban block with a tighter grain to the South. There are no pedestrian routes through the block and a long unbroken frontage is presented to Shoreditch High Street/ Norton Folgate. This consists of the former Nicholls and Clarke buildings, which are comprised of 2 show rooms and warehouses to the North. The triangular shaped plot of the S1c site contains the 1887 warehouse, various low level outbuildings and electrical substation. It is bounded to the North by the mainline train lines running to and from Liverpool Street station. 3 Plots S1 and S1c are separated by Fleur De Lis Passage, a pedestrian right of way, linking Shoreditch High Street with Fleur De Lis and Blossom Street. S1 has two primary facades 4 with East West orientation; one along Shoreditch High Street; the other to the narrow Blossom Street. The Southern boundary of S1 is Folgate Street where both plots S1a and S1b are located, with the existing courtyard of Blossom Place separating the larger warehouse buildings from the smaller plots making up S1a and S1b. Blossom Street is characterised by late Victorian warehouses, reflecting the functional back to Nicholls and Clark whilst the facade to Shoreditch High Street is Art Deco in style forming 6 a civic shop front. -

Excavations at Crispin Street, Spitalfields: from Roman Cemetery to Post-Medieval Artillery Ground

EXCAVATIONS AT CRISPIN STREET, SPITALFIELDS: FROM ROMAN CEMETERY TO POST-MEDIEVAL ARTILLERY GROUND Berni Sudds and Alistair Douglas with Christopher Phillpotts† With contributions by John Brown, Natasha Dodwell, Märit Gaimster, James Gerrard, Chris Jarrett, Malcolm Lyne, Quita Mould, Kathelen Sayer, John Shepherd and Lisa Yeomans SUMMARY which was evidenced by the discovery of an early 18th- century cattle horn core lined cesspit. There was also This article describes archaeological investigations indirect evidence for clay tobacco pipe manufacture undertaken by Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd on land locally during c.1660 to 1680. off Crispin Street, Spitalfields, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. A total of 36 Roman inhumation INTRODUCTION burials dating from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, forming part of the extra-mural cemetery alongside The site lies to the north-east of the City of Ermine Street were identified. Unusual burials includ- London within Spitalfields and is bounded ed a decapitated individual. to the north by housing fronting on to During the late 13th century the site was bisected by Brushfield Street and to the east, south and the outer precinct boundary of the Priory and Hospital west by Crispin Street, Artillery Lane and of St Mary Spital. This boundary which was delin- Gun Street respectively (NGR TQ 3355 8170; eated by a ditch and bank was to remain extant in one site code CPN01) (Figs 1 & 2). In advance form or another on roughly the same alignment until of proposed redevelopment Pre-Construct the present development. Just prior to the Dissolution Archaeology Ltd was commissioned to in 1538 a brick wall was constructed around the outer undertake archaeological investigations precinct, which was leased to the Guild of Artillery of on site by the Manhattan Loft Corporation Longbows, Crossbows and Handguns for the purpose Ltd and Osbourne Group. -

United Trade Action Group V TFL Judgment

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWCA Civ 1197 Case No: C1/2021/0227/QBACF IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT THE HON MRS JUSTICE LANG C/2854 and 2995/2020 Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 30/07/2021 Before : LORD JUSTICE BEAN SIR KEITH LINDBLOM, SENIOR PRESIDENT OF TRIBUNALS and SIR STEPHEN IRWIN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between THE QUEEN ON THE APPLICATION OF Claimants/ (1) UNITED TRADE ACTION GROUP LTD Respondents (2) LICENSED TAXI DRIVERS ASSOCIATION LTD - and - (1) TRANSPORT FOR LONDON Defendants/ (2) MAYOR OF LONDON Appellants - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ben Jaffey Q.C. and Celia Rooney (instructed by Public and Regulatory Law Team, Transport for London) for the Appellants (Defendants) David Matthias Q.C. and Charles Streeten (instructed by Chiltern Law) for the Respondents (Claimants) Hearing dates : 15 and 16 June 2021 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. United Trade Action Group Ltd v TfL Lord Justice Bean, the Senior President of Tribunals and Sir Stephen Irwin: Introduction 1. This is the judgment of the court, to which we have all contributed. 2. In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, in May 2020, did Transport for London (“TfL”) and the Mayor of London (“the Mayor”) act unlawfully in preparing and publishing the London Streetspace Plan (“the Plan”) and the London Streetspace Plan – Interim Guidance to Boroughs (“the Guidance”), because when doing so they failed – it is said – properly to consider the interests of licensed taxi drivers? And did TfL, in making the A10 GLA Roads (Norton Folgate, Bishopsgate and Gracechurch Street, City of London) (Temporary Banned Turns and Prohibition of Traffic and Stopping) Order 2020 (“the A10 Order”) in July 2020, fall into error in the same way? These are the basic questions in this case. -

Approved Judgment

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWHC 72 (Admin) Case No: CO/2854/2020 & CO/2995/2020 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION PLANNING COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 20 January 2021 Before : MRS JUSTICE LANG DBE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : CO/2854/2020 THE QUEEN Claimants on the application of (1) UNITED TRADE ACTION GROUP LIMITED (2) LICENSED TAXI DRIVERS ASSOCIATION LIMITED - and - (1) TRANSPORT FOR LONDON Defendants (2) MAYOR OF LONDON CO/2995/2020 THE QUEEN Claimants on the application of (1) UNITED TRADE ACTION GROUP LIMITED (2) LICENSED TAXI DRIVERS ASSOCIATION LIMITED - and - TRANSPORT FOR LONDON Defendant David Matthias QC and Charles Streeten (instructed by Chiltern Law) for the Claimants Ben Jaffey QC and Celia Rooney (instructed by the Public and Regulatory Law Team, Transport for London) for the Defendants Hearing dates: 25 & 26 November 2020 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. R(UTAG and Anor) v TfL and Anor Mrs Justice Lang: 1. In two consolidated claims for judicial review, the Claimants challenge the London Streetspace Plan (“the Plan”) and the “Interim Guidance to Boroughs” (“the Guidance”) and the A10 GLA Roads (Norton Folgate, Bishopsgate and Gracechurch Street, City of London (Temporary Banned Turns and Prohibition of Traffic and Stopping) Order 2020 (the “A10 Order”). 2. The First Claimant (“UTAG”) is a trade body formed to protect the interests of the hackney carriage industry in London. The Second Claimant (“LTDA”) is a long- established trade body representing the interests of hackney carriage drivers. For ease, I shall refer to hackney carriages as “taxis” in this judgment. -

Former Nicholls & Clarke Site, Shoreditch

planning report PDU/2656 & 2656a/02 24 August 2011 Former Nicholls & Clarke site, Shoreditch in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets planning application no.PA/10/02764 & PA/10/02765 Strategic planning application stage II referral (new powers) Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 The proposal A full planning application for the redevelopment of two adjacent sites for commercially-led mixed use purposes, comprising buildings between 4 and 8 storeys (plus plant), to provide B1 (Office); retail and restaurants and public house. The applicant The applicant is City of London Corporation, and the architects are Avanti Architects. Strategic issues Outstanding issues that were raised at Stage 1 in relation to transport and climate change mitigation & adaptation are now resolved satisfactorily. It is noted that the housing element of the application is removed in the amended scheme. The Council’s decision In this instance Tower Hamlets Council has resolved to grant permission but giving delegated authority for officers to refuse permission if the Section 106 agreement is not signed within a specified date. Recommendation That Tower Hamlets Council be advised that the Mayor is content for it to determine the case itself, subject to any action that the Secretary of State may take, and does not therefore wish to direct refusal or direct that he is to be the local planning authority. Context 1 On 30 December 2010 the Mayor of London received documents from Tower Hamlets Council notifying him of a planning application of potential strategic importance to develop the above site for the above uses. -

Committee: Strategic Development Date: 21St July 2015 Classification: Unrestricted Agenda Item Number: Report Of: Director of De

Committee: Date: Classification: Agenda Item Number: Strategic 21st July 2015 Unrestricted Development Report of: Title: Applications for Planning Permission and Director of Development and Listed Building Consent. Renewal Ref No: PA/14/03548 (Full Planning Application) Case Officer: Ref No. PA/14/3618 (Listed Building Consent) Adam Hussain Ward: Spitalfields and Banglatown 1. APPLICATION DETAILS Location: Land bounded by Elder Street, Folgate Street, Blossom Street, Norton Folgate, Shoreditch High Street and Commercial Street, E1. Existing Use: Retail (A1), Public House (A4), Office (B1), Storage and Distribution (B8) and Non-Residential Institutions (D1). Proposal: Application for planning permission (PA/14/03548) Redevelopment of the former Nicholls and Clarke urban block and adjoining former depot site, Loom Court, and land and buildings north of Fleur de Lis Passage and Fleur de Lis Street, including retention and refurbishment of buildings, for commercially led mixed- use purposes comprising buildings of between 4 and 13 storeys to provide B1 (Office), A1 (Retail), A3 (Restaurants and cafés), A4 (Public house) and 40 residential units; together with new public open spaces and landscaping, new pedestrian accesses, works to the public highway and public realm, the provision of off-street parking, and ancillary and enabling works, plant and equipment. The application is accompanied by an Environmental Statement, Addendum and other environmental information. The Council shall not grant planning permission unless they have taken the environmental information into consideration. Application for listed building consent (PA/14/03618) Works to the public highway (Fleur de Lis Street) including repair and replacement, where necessary, of the carriageway and pavement, installation of cycle parking, hard landscaping and all necessary ancillary and enabling works, plant and equipment. -

PDU Case Report XXXX/YY Date

planning report D&P/2656b/01 18 March 2015 Land at Blossom Street, Spitalfields in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets Strategic planning application stage 1 referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 The proposal Redevelopment of the former Nicholls and Clarke urban block and adjoining former depot site, Loom Court and land and buildings north of Fleur de Lis Passage and Fleur de Lis Street, including retention and refurbishment of buildings, for commercially-led mixed use purposes comprising buildings of between four and thirteen storeys to provide B1 (office), A1 (retail), A3 (restaurants and cafes), A4 (public house) and residential Units; together with new public open spaces/landscaping, new pedestrian routes, works to the public highway and public realm, provision of off-street car parking, and all necessary ancillary and enabling works, plant and equipment. The applicant The applicant is British Land, the architects are AHMM, Duggan Morris, Stanton Williams, DSDHA and East, the agent is DP9. Strategic issues The principle of commercially-led development on this site is strongly supported in strategic planning terms. Outstanding issues with regards to mix of uses, housing, urban design, energy and transport should, nevertheless, be resolved before the application is referred back to the Mayor. Recommendation That Tower Hamlets Council be advised that while the application is generally acceptable in strategic planning terms the application does not comply with the London Plan, for the reasons set out in paragraph 96 of this report; but that the possible remedies set out in paragraph of this report could address these deficiencies. -

Blossom-Street-Boards-Final LR.Pdf

Welcome to our exhibition of the proposals for the group of buildings collectively known as Blossom Street. Our proposals are currently being finalised for a planning submission in December 2014, following extensive engagement with our neighbours, local residents, community groups and all those with an interest in the development of this unique area. Our exhibition today will show you how the proposals have changed SHOREDITCH HIGH STREET during the public consultation and how your feedback has influenced and shaped the design process. In August 2013, British Land entered into an agreement with the City of London Corporation, the freeholders, to look at options for the BLOSSOM STREET regeneration of Blossom Street. FOLGATE STREET British Land intends to submit a planning application for Blossom Street before the end of 2014 and, if approved, will acquire a long- term leasehold interest from the City of London Corporation. If you wish to be kept informed as the project progresses, please make sure you fill out one of our comment cards. ELDER STREET Thank you for coming today. COMMERCIAL STREET FLEUR DE LIS STREET Aerial photograph showing the group of buildings collectively known as Blossom Street Blossom Street Fleur De Lis Street WELCOME In 2011, the City of London secured a planning consent for the redevelopment of part of the Blossom Street group of buildings. The permission remains active and one option for the redevelopment would be to build in line with these existing plans, where appropriate. Having reviewed the existing consent in detail, British Land feel there is an opportunity to develop the site with a greater level of sensitivity to the surrounding Conservation Area.