The Marriage of Figaro Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

Mozart's Operas, Musical Plays & Dramatic Cantatas

Mozart’s Operas, Musical Plays & Dramatic Cantatas Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebotes (The Obligation of the First and Foremost Commandment) Premiere: March 12, 1767, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Apollo et Hyacinthus (Apollo and Hyacinth) Premiere: May 13, 1767, Great Hall, University of Salzburg Bastien und Bastienne (Bastien and Bastienne) Unconfirmed premiere: Oct. 1768, Vienna (in garden of Dr Franz Mesmer) First confirmed performance: Oct. 2, 1890, Architektenhaus, Berlin La finta semplice (The Feigned Simpleton) Premiere: May 1, 1769, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Mitridate, rè di Ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus) Premiere: Dec. 26, 1770, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan Ascanio in Alba (Ascanius in Alba) Premiere: Oct. 17, 1771, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan Il sogno di Scipione (Scipio's Dream) Premiere: May 1, 1772, Archbishop’s Residence, Salzburg Lucio Silla (Lucius Sillus) Premiere: Dec. 26, 1772, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan La finta giardiniera (The Pretend Garden-Maid) Premiere: Jan. 13, 1775, Redoutensaal, Munich Il rè pastore (The Shepherd King) Premiere: April 23, 1775, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Thamos, König in Ägypten (Thamos, King of Egypt) Premiere (with 2 choruses): Apr. 4, 1774, Kärntnertor Theatre, Vienna First complete performance: 1779-1780, Salzburg Idomeneo, rè di Creta (Idomeneo, King of Crete) Premiere: Jan. 29, 1781, Court Theatre (now Cuvilliés Theatre), Munich Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) Premiere: July 16, 1782, Burgtheater, Vienna Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom) Composed: 1784, but the opera was never completed *Not performed during Mozart’s lifetime Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario) Premiere: Feb. 7, 1786, Palace of Schönbrunn, Vienna Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) Premiere: May 1, 1786, Burgtheater, Vienna Don Giovanni (Don Juan) Premiere: Oct. -

Overture to the Marriage of Figaro

Integrated subject areas: Music English Language Arts Overture to The Marriage Social Emotional Learning of Figaro: Compare and Grade(s): 4-6 Lesson length: 40 minutes Contrast Instructional objectives: Students will: Learn about Mozart’s life DESCRIPTION Identify basic musical elements: tempo, dynamics, instrumentation and melody Compare and contrast two different musical styles using Students will listen to two pieces of music with similar melodies, but in the same basic melody completely different styles. One piece is the overture to The Marriage of Compose a review as a music Figaro, an opera in four acts written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1786. critic The other is a modern interpretation of the same piece of music by the East Village Opera Company. Materials: Musical recordings of the Students will explore instrumentation, tempo, dynamics, and style used featured repertoire listed within these two pieces. above Sound system for musical Assessment Strategies excerpts of concert repertoire (e.g. laptop and speakers, In this lesson, students should be able to successfully do the following: iPhone® dock, Spotify®, etc) discuss basic musical elements such as tempo, dynamics, instrumentation Paper and writing utensil and melody; differentiate between two musical works with the same melody but very different styles, through class discussion and a writing Featured Repertoire*: assignment. Learn more about assessment strategies on page 5. Mozart – Overture to The Marriage of Figaro Learning Standards East Village Opera Company – Overture Redux (Le Nozze Di This lesson uses Common Core and National Core Arts Anchor Figaro) Standards. You can find more information about the standards featured in this lesson on page 4. -

CHAN 3093 BOOK.Qxd 11/4/07 3:30 Pm Page 2

CHAN 3093 Book Cover.qxd 11/4/07 3:23 pm Page 1 GREAT OPERATIC ARIAS GREAT OPERATIC ARIAS CHAN 3093 CHANDOS O PERA IN DIANA MONTAGUE ENGLISH 2 PETER MOORES FOUNDATION CHAN 3093 BOOK.qxd 11/4/07 3:30 pm Page 2 Diana Montague at the recording sessions Cooper Bill Great Operatic Arias with Diana Montague 3 CHAN 3093 BOOK.qxd 11/4/07 3:30 pm Page 4 Time Page Time Page Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) from Atalanta from The Marriage of Figaro Meleagro’s aria (Care selve) Cherubino’s Aria (Non so più) 6 ‘Noble forests, sombre and shady’ 2:05 [p. 46] Alastair Young harpsichord • Susanne Beer cello 1 ‘Is it pain, is it pleasure that fills me’ 3:07 [p. 44] from The Clemency of Titus Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sextus’s Aria (Parto, parto) from Così fan tutte 2 6:39 [p. 44] ‘Send me, but, my beloved’ Fiordiligi, Dorabella and Don Alfonso’s Trio (Soave sia il vento) Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714–1787) 7 ‘Blow gently, you breezes’ 3:33 [p. 46] with Orla Boylan soprano • Alan Opie baritone from Iphigenia in Tauris Priestesses’ Chorus and Iphigenia’s Aria (O malheureuse Iphigénie!) Dorabella’s Recitative and Aria (Smanie implacabili) 3 ‘Farewell, beloved homeland’ – 8 ‘Ah! Leave me now’ – ‘No hope remains in my affliction’ 4:56 [p. 45] ‘Torture and agony’ 3:39 [p. 46] with Geoffrey Mitchell Choir Dorabella and Fiordiligi’s Duet (Prenderò quel brunettino) Iphigenia’s Aria (Je t’implore et je tremble) 9 ‘I will take the handsome, dark one’ 3:07 [p. -

669031 Bk Salerni

669032-33 bk Aldridge US 27/4/11 12:51 Page 48 AMERICAN OPERA CLASSICS ROBERT ALDRIDGE Elmer Gantry Libretto by Herschel Garfein Phares • Risley • Rideout • Kelley • Buck Florentine Opera Chorus • Florentine Opera Company Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra • William Boggs 2 CDs 8.669032-33 48 669032-33 bk Aldridge US 27/4/11 12:51 Page 2 Robert Livingston ALDRIDGE (b. 1954) Elmer Gantry (2007) An Opera in Two Acts Libretto by Herschel Garfein based on the novel by Sinclair Lewis Elmer Gantry . Keith Phares Sharon Falconer . Patricia Risley Frank Shallard . Vale Rideout Eddie Fislinger . Frank Kelley Lulu Baines . Heather Buck Reverend Arthur Baines . Matthew Lau T.J. Rigg . Jamie Offenbach Mrs. Baines . Julia Elise Hardin Revival Singer . William Johnson Binch/Bully/Worker #1 . Aaron Blankfield Keely Family Singers . .Sarah Lewis Jones / Linda S. Ehlers / Paul Helm / Nathan Krueger Reporter . Peter C. Voigt Revival Worker/Worker #2 . Scott Johnson Ice Cream Vendor . Matthew Richardson Child . Katie Koester Man #1 . James Barany Woman #1 . Tracy Wildt Woman #2 . Kristin Ngchee Tour Guide . Margaret Wendt Women’s Chorus Leader . Julie Alonzo-Calteaux Florentine Opera Chorus Chorus-master: Scott Stewart Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra • William Boggs 8.669032-33 2 47 8.669032-33 669032-33 bk Aldridge US 27/4/11 12:51 Page 46 Director: John Hoomes • Producer/General Director: William Florescu Musical Preparation: Jamie Johns • Off-Stage Piano: Anne Van Deusen Producer and editor: Blanton Alspaugh (Soundmirror.com) Recording engineers: John Newton and Byeong-Joon Hwang Mixing/mastering engineer: Jesse Lewis Production Sponsors: Donald and Donna Baumgartner Keith Phares’s performance generously sponsored by the Marie Z. -

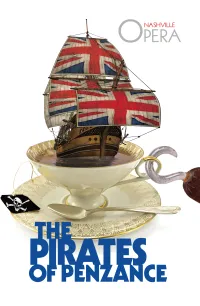

Programpirates20.Pdf

THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE A comic opera in two acts with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert Premiere at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in New York City on December 31, 1879 April 9 & 11, 2015 Andrew Jackson Hall, Tennessee Performing Arts Center Conducted by William Boggs • Directed by Dean Anthony** CAST Pirate King Craig Irvin Major General Stanley Curt Olds* Ruth Maria Zifchak* The Bovender Principal Artist Police Sergeant Aaron Sorensen* Mabel Hanna Brammer*† Frederic Christopher Nelson*† Samuel Alex Soare*† Edith Christine Amon*† Isabel Emily Apuzzo Hopkins Kate Brooke Hazen CREATIVE TEAM Lighting Designer Joe Saint Assistant Lighting Designer Andrea Boccanfuso Costume Coordinator Pam Lisenby Wigs and Make-up Designer Sondra Nottingham Props Master Robert Gilmer Accompanist/Chorusmaster Amy Tate Williams Production Stage Manager Kat Slagell PRODUCTION CREDITS Set design by Chris Clapp • Scenery provided by Opera Carolina Costumes provided by A.T. Jones & Sons, Inc. Technical Director James Lile Assistant Stage Manager Valerie Clatworthy Wigs and Make-up Crew Steven Young, Brecque Jameson, Kristin Anderson Kathryn Conde, Amanda Romese Costume Crew Annie Freeman, Jayme Locke, Don Skelton Props Crew Dan Weikal Supernumerary Coordinator Michael Rutter Supertitles Creator John Hoomes * Nashville Opera Debut ** Nashville Opera Directing Debut † 2015 Mary Ragland Young Artist THE STORY ACT I the bunch, Mabel. She graciously offers to reclaim this “Poor Wandering One” from his life of villainy. The young apprentice Frederic has just come to All seems close to ending happily, but unfortunately the end of his indentured period with the notorious Frederic has forgotten that there are pirates about! Pirates of Penzance. -

Section 2 Stage Works Operas Ballets Teil 2 Bühnenwerke

SECTION 2 STAGE WORKS OPERAS BALLETS TEIL 2 BÜHNENWERKE BALLETTE 267 268 Bergh d’Albert, Eugen (1864–1932) Amram, David (b. 1930) Mister Wu The Final Ingredient Oper in drei Akten. Text von M. Karlev nach dem gleichnamigen Drama Opera in One Act, adapted from the play by Reginald Rose. Libretto by von Harry M. Vernon und Harald Owen. (Deutsch) Arnold Weinstein. (English) Opera in Three Acts. Text by M. Karlev based on the play of the same 12 Solo Voices—SATB Chorus—2.2.2.2—4.2.3.0—Timp—2Perc—Str / name by Harry M. Vernon and Harald Owen. (German) 57' Voices—3.3(III=Ca).2(II=ClEb).B-cl(Cl).3—4.3.3.1—Timp—Perc— C F Peters Corporation Hp/Cel—Str—Off-stage: 1.0.Ca.0.1—0.0.0.0—Perc(Tamb)—2Gtr—Vc / 150' Twelfth Night Heinrichshofen Opera. Text adapted from Shakespeare’s play by Joseph Papp. (English) _________________________________________________________ 13 Solo Voices—SATB Chorus—1.1.1.1—2.1.1.0—Timp—2Perc—Str C F Peters Corporation [Vocal Score/Klavierauszug EP 6691] Alberga, Eleanor (b. 1949) _________________________________________________________ Roald Dahl’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Text by Roald Dahl (English) Becker, John (1886–1961) Narrator(s)—2(II=Picc).2.2(II=B-cl).1.Cbsn—4.2.2.B-tbn.1—5Perc— A Marriage with Space (Stagework No. 3) Hp—Pf—Str / 37' A Drama in colour, light and sound for solo and mass dramatisation, Peters Edition/Hinrichsen [Score/Partitur EP 7566] solo and dance group and orchestra. -

The Marriage of Figaro 4

Dynamic Surprises UNIT Focal Work: Mozart’s Overture to The Marriage of Figaro 4 Aim: How do unexpected dynamic changes create musical movement? Summary: We analyze dynamic change and contrast in Mozart’s Overture to The Marriage of Figaro. Materials: colored pencils or markers, staff paper Time Requirement: three 20-minute sessions Standards: US 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8; NYC 1, 2, 3 Vocabulary: overture, opera, dynamics, tempo Unit 4 Overview Activity 4.1: What is an Overture? Activity 4.2: Overture to The Marriage of Figaro Listening Map Creative Extension 1: Overture to The Marriage of Figaro Dynamics Map Activity 4.3: Get Things Moving with Dynamic Surprises Creative Extension 2: Draw Your Own Cartoon Story Activity 4.1: What is an Overture? • How do all TV programs—cartoons, news, soap operas—begin? • Why would you want music at the beginning of a TV program? • What are some of your favorite TV theme songs, and how does the music connect with the program? • Play Overture to The Marriage of Figaro, Track 31. • What kind of show would this music introduce? • Introduce and define the overture and story from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro. The Marriage of Figaro opera: Contouris an opera that tells a live theater show in a funny story about a which the characters whirlwind day f illed sing what they’re with confusion, chaos, saying instead of surprises, tricks, talking to each other and a happy ending. The The Overture to overture: Marriage of Figaro instrumental music uses slow and fast tempos as well as that acts as the introduction to loud and soft dynamics an opera to represent the different characters of the opera and all theContour tricks they play on each other. -

An Operatic Glossary

An Operatic Glossary This is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to opera jargon, only a quick look-up for words and phrases in the novel that may have stopped the eye of, or excited the interest of, a reader. Entries are in alphabetical order, ignoring only initial ‘the’ and its foreign-language equivalents. The date given for an opera is the date of first performance. An expression like “2.ix” after the opera’s name indicates “act two, scene nine” of the opera, as most commonly performed. Arias are mostly referred to by their first few words. I have filled this out to a full sentence, or as much of one as seemed required to give some flavor of the aria’s meaning and dramatic point, where these are not plain in the novel. My references to “the standard repertory” should not be taken too seriously. To the best of my knowledge, the International Standards Orga- nization does not issue rulings on opera production. “The standard rep- ertory” is merely a shorthand for “the few dozen operas most frequently performed”. It is to some degree a child of fashion. As years go by, operas, composers, and even entire genres enter, exit, or re-enter the stan- dard repertory. Fifty years ago, for example, there was less Italian opera (and much less bel canto) than there is today. 253 3797-DERB JOHN DERBYSHIRE * * * a cappella Sung without any instrumental accompaniment, as “in the chapel”. Ah, fors’ è lui . che l’anima solinga ne’ tumulti godea sovente pingere. “Ah, perhaps it’s he that my soul, alone in the tumult of pleasure, has so often pictured.” Aria from Verdi’s La traviata, 1.v. -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart A. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) I

Student Study Outline Chapter 33: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart I. Chapter 33: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart a. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) i. Child prodigy who began composing at age five ii. Leading keyboard virtuoso iii. Short life and financially insecure b. Mozart’s Life and Career i. Born to a musical family in Salzburg, Austria ii. Father Leopold took his children on an international tour in 1763 iii. 1772– invited to join the court musicians by archbishop of Salzburg iv. 1781– wrote an Italian opera to be presented in Munich v. Vienna– turning point in his career c. Making Connections: Mozart as Freemason i. Joined the Freemasons in 1784 d. Mozart’s Music i. Over 600 compositions ii. Cataloged in the 19th century by Ludwig von Köchel iii. Operas– performed often 1. Italian– The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni 2. German– The Abduction from the Seraglio, The Magic Flute iv. Sacred music v. Symphonies 1. No. 40 in G minor 2. No. 41 in C major (Jupiter) vi. Nearly 40 concertos vii. Chamber music e. Making Connections: Mozart and Posterity i. Legends f. Mozart and the Classical Concerto i. Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488, First Movement Listening Map 29 1. First movement a. Tutti b. Solo c. Cadenza g. Mozart and Italian Opera i. C.W. Gluck (1714–1787) 1. Gluck’s reforms influenced Mozart ii. Opera seria iii. Opera buffa 1. The Marriage of Figaro a. Mozart, The Marriage of Figaro, K. 42, Act I, Scene 1, Figaro and Susanna, “Se a casa madama” (1786) Listening Map 30 b. -

Le Nozze Di Figaro

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART le nozze di figaro conductor Opera in four acts Antonello Manacorda DEBUT Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte, production based on the play La Folle Journée, Sir Richard Eyre ou Le Mariage de Figaro by Pierre-Augustin set and costume designer Caron de Beaumarchais Rob Howell Saturday, November 16, 2019 lighting designer 1:00–4:30 PM Paule Constable choreographer First time this season Sara Erde revival stage director Jonathon Loy The production of Le Nozze di Figaro was made possible by generous gifts from Mercedes T. Bass, and Jerry and Jane del Missier The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from the Metropolitan Opera Club general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2019–20 SEASON The 494th Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S le nozze di figaro conductor Antonello Manacorda DEBUT in order of vocal appearance figaro antonio Luca Pisaroni Paul Corona susanna barbarina Nadine Sierra Meigui Zhang** dr. bartolo don curzio Brindley Sherratt Tony Stevenson* marcellina Elizabeth Bishop continuo harpsichord Linda Hall cherubino cello David Heiss Gaëlle Arquez DEBUT count almaviva Adam Plachetka This performance is being broadcast don basilio live on Metropolitan Giuseppe Filianoti Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 75 countess almaviva and streamed at Susanna Phillips metopera.org. Saturday, November 16, 2019, 1:00–4:30PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene Chorus Master Donald Palumbo from Mozart’s Fight Director Thomas Schall Le Nozze di Figaro Assistant -

000000015 1.Pdf

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE CLOSING OF MARTINŮ REVISITED ’ HUMOUR IN MARTINŮ S MUSIC JANUARY—APRIL 2011 VOL.XI NO.1 HISTORIC LPs AUTOGRAPHS IN THE MÉDIATHÈQUE MUSICALE MAHLER NEW PUBLICATIONS & CDs NEW CD MARTINŮ. THE 6 SYMPHONIES contents Recorded Live 3 highlights / events BBC Symphony Orchestra, Jiří Bělohlávek (Conductor) 4 incircle news Onyx Classics, ONYX4061 3CD (due for release in June 2011) 6 news International Martinů Circle Founding Members Closing Concert of the Martinů PEEPH●●LE Revisited Project 8 Martinů Revisited 2009–2010 INTO THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŲ CENTER IN POLIČKA ALEŠ BŘEZINA 10 Historic Recordings for the Library of the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation ZOJA SEYČKOVÁ 11 special series List of Martinů’s Works XI 12 festivals Martinů as a Source of Inspiration CHRISTINE FIVIAN & CECILE PIERBURG 14 research Humour in Martinů’s Music from the 1920s EVA VELICKÁ MARTINŮ OWNED a Kopecký & Co. piano that he kept at his music school in today’s Masary kova Street in Polička and on which he wrote a number of compositions. We do not know exactly 17 research when and from whom he bought the instrument, yet from 1919 he endeavoured to sell it. New Martinů Autographs in Paris When in 1932 the piano was bought by his friend, the Polička-based builder Bohuslav Šmíd, ALEŠ BŘEZINA Martinů expressed his gratitude by writing several minor piano pieces for his children bearing the dedication “To Božánek and Sonička Šmíd“. Martinů was delighted that the piano was in good hands, as is evident from the letter he wrote to Šmíd in Paris on 16 May 1932: 18 events / news “You understand that I parted with it with regret, since it is a friend that collaborated with me on my things, and it cost me a lot of effort to acquire it – I had to write a good few notes to pay for it.