Bridging the Gap the Representation of Solidarity in the Music of Pride (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Jimmy Somerville Manage the Damage Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jimmy Somerville Manage The Damage mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Manage The Damage Country: Japan Released: 1999 Style: Downtempo, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1770 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1975 mb WMA version RAR size: 1228 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 930 Other Formats: AUD WAV MP3 ADX AC3 DTS MP1 Tracklist 1 Here I Am 2 Lay Down 3 Dark Sky 4 My Life 5 Something To Live For 6 This Must Be Love 7 Girl Falling Down 8 Someday Soon 9 Eve 10 Stone 11 Rolling Bonus Track: 12 Lay Down (Almighty Vocal Mix) Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Rock Records (Japan) Co. Ltd. – RCCY-1081 Credits Producer – Jimmy Somerville, Sally Herbert Written-By – Jimmy Somerville, Sally Herbert Notes Recorded in London at Peg's Study, Mayfair, Battery, Townhouse and RAK. Made in Japan. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4 516192 120700 Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) Manage The Jimmy GUT CD8 Damage (CD, Gut Records GUT CD8 UK 1999 Somerville Album) Manage The SPV 085-23082 Jimmy Damage (CD, SPV 085-23082 Gut Records Russia 1999 CD Somerville Album, CD Unofficial) Manage The Jimmy Czech ERA 9906-2 Damage (CD, Nextera ERA 9906-2 1999 Somerville Republic Album) Manage The Planetworks, 542 271-2, Jimmy 542 271-2, Damage (CD, Mercury Greece 1999 MERC-542271-2 Somerville MERC-542271-2 Album) Records Blanco Y Manage The MXCD 982, MXCD Jimmy Negro , Blanco MXCD 982, MXCD Damage (CD, Spain 1999 982 (CS) Somerville Y Negro , Gut 982 (CS) Album) Records Related Music albums to Manage The Damage by Jimmy Somerville Jimmy Somerville - Hurt So Good Amanda Somerville - Never Alone Jimmy Somerville - Dark Sky Jimmy Somerville - Why (Almighty Mixes) Jimmy Somerville - Safe Jimmy Somerville - To Love Somebody (Definitive Mix) Communards - The 12" Singles / An Interview With Jimmy Somerville and Richard Coles Jimmy Somerville Featuring Bronski Beat And The Communards - The Singles Collection 1984/1990 Jimmy Somerville - Collection 1984/1990 vol.1 Jimmy Somerville - Best Of '99. -

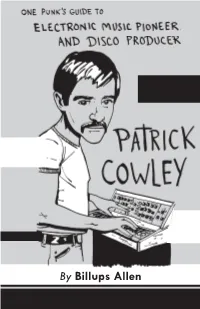

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Is a Record Store Clerk Who Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen is a record store clerk who spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and film minor. He currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he publishes Cramhole zine, contributes regularly to Razorcake, Lunchmeat, and Ugly Things, and writes fiction (cramholezine.com, billupsallen@ gmail.com) Illustrations by Danny Martin: Zines, murals , stickers, woodcuts, and teachin’ screen printing at a community college on the side. (@DannyMartinArt) Zine design by Todd Taylor Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. One Punk’s Guide to Patrick Cowley originally appeared in Razorcake #107, released in December 2018/January 2019. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles Arts Commission. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org n 1978 a DJ subscription-only remix of the already popular Donna Summer song “I Feel Love” went out in the mail. It was 15:43 long. The bass line was looped so overdubbed synthesizer effects could be added. This particular version of the song went largely unnoticed by the general public and did nothing to make producer Patrick Cowley a household name. But dancers in nightclubs reacted. They may have been unaware and/or unconcerned about what they were hearing, but they reacted. -

1980S Retro Playlist

1980s Retro Playlist Instructor Song Name Time Artist BPM Contributor Uses Take A Chance On Me 4:07 Abba 107 Lisa Piquette I love this for an opening song Richard Poison Arrow 3:24 ABC 126 Newman intro song while class is setting up I Saw the Sign 3:12 Ace of Base 97 J Sage fast flat. Great for cadence drills My roommate at UCSB was in love with Adam Ant, so I can't think of the 1980s without thinking of her and this song! It has a great beginning for your cyclists; there's no way to not grab that distinctive drum Goody Two Shoes 3:28 Adam Ant 95 J Sage beat for your higher-cadence flats. Take On Me 3:47 Aha 84 Lisa Piquette Fast Cadence, Hill Back to the 80s 3:43 Aqua Annette Warm up Freeway of Love 5:33 Aretha Franklin 126 Lisa Piquette Cadence Surges Venus 3:37 Bananarama 126 Lisa Piquette Muscular Endurance Richard Take My Breath Away 4:12 Berlin 96 Newman cool down In my Top 5 for sure. I thought this song was so unique at the time—it didn't sound like many of the other typical songs of the era. The Scottish accents and the bagpipes gave it an exotic sound. I use this in almost all of my retro playlists. You can only climb to it, and at 2:28 you power out of the saddle after Big Country 3:55 Big Country 125 J Sage he sings "When every single hope has been shattered" until 2:45. -

Jimmy Somerville - the Official Biography

JIMMY SOMERVILLE - THE OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHY The unmistakable voice of Bronski Beat and The Communards, featured on massive hits such as Smalltown Boy and Don't Leave Me This Way – it can be none other than Jimmy Somerville. Bronski Beat not only introduced the world to Jimmy's unique voice, their debut smash hit Smalltown Boy tackled pertinent social issues with it’s lyric addressing the isolation and rejection felt by a provincial gay youth forced into leaving town. Although not the first pop song to deal with this topic, Bronski Beat’s chart friendly early 80's electronic dance sound and the everyday ordinariness and honesty of the three performers, made Smalltown Boy the biggest record about gay issues there'd ever been. Jimmy’s next band The Communards enjoyed a string of hits from their two hit albums Communards (1986) and Red (1987). One moment the Communards were hurtling to the number one spot - a position they held for weeks in the UK in 1986 - with their energetic, hedonistic cover version of the Philly soul classic Don't Leave Me This Way, the next stunning audiences into silent awe with their touching lament for a loved one lost to AIDS, For A Friend. 1989 saw Jimmy embark on a solo career with 5 more hit singles and two albums; Read My Lips (1989) and The Singles Collection (1990). These included a stirring cover of Sylvester's disco anthem You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real). Jimmy's continued outspokenness on gay issues didn't prevent his records being played and selling in huge quantities. -

80'S 298 Songs, 19.4 Hours, 1.98 GB

80's 298 songs, 19.4 hours, 1.98 GB Name Artist Africa Toto All Night Long Lionel Richie Always Something There To Remind Me Naked Eyes And She Was Talking Heads And she was Talking Heads And We Danced The Hooters Angel of Harlem U2 Antmusic Adam & The Ants Back To Life Soul II Soul Bamboleo Gypsy Knings Beast Of Burden Bette Midler A Beat For You Pseudo Echo Beat It (Single Version) Michael Jackson Because the night belongs to lovers Natalie Merchant Bette Davis Eyes Kim Carnes Big Fun Inner City Billie Jean (Single Version) Michael Jackson Blister in the Sun Violent Femmes Blue Monday New Order Boom Boom Boom Paul Lekakis Borderline Madonna Born to Run Bruce Springsteen Boys (Summertime Love) Sabrina Break My Stride Matthew Wilder Bridge To Your Heart WAX Bufalo Stance Neneh Cherry C'est La Vie Robbie Nevil Call Me Blondie Centrefold J. Geils Band Chain Reaction Diana Ross Cherish Madonna Cherry Lady Modern Talking The Clapping Song The Belle Stars Cocaine Eric Clapton Come on Eileen Dexy's Midnight Runners Conga Various Artists Copperhead Road Steve Earle Could You Be Loved Bob Marley & The Wailers Crazy For You Madonna Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Cruel Summer Bananarama Dangerous Roxette Do You Really Want To Hurt Me Culture Club Don't Forget Me (When I'm Gone) Glass Tiger Don't Go Yazoo Don't Leave Me This Way The Communards Don't Leave Me this Way Communards Don't Tell Me The Time Martha Davis Don't You Simple Minds Don't You Want Me Human League Down On The Border Little River Band Down Under Men At Work Dressed For Success -

Popular Music and Gays, Lesbians, Bisexuals, and Transgender People: an Annotated Bibliography and Discography

Page 1 of 35 Popular Music and Gays, Lesbians, Bisexuals, and Transgender People: An Annotated Bibliography and Discography. Compiled by Walt “Cat” Walker. Approved by the GLBTRT Resources Committee. Last revised January 12, 2017. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 I. General Nonfiction 3 II. Memoirs & Biographies 9 III. Fiction 32 IV. Drama 33 V. Children & Teens 34 VI. DVDs 35 Page 2 of 35 Introduction Gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people have always participated in creating popular music. In recent years, the visibility of LGBTQ people in the music world has increased, and more popular music has been created that openly describes the LGBTQ experience. There has also been an increase in books and films related to LGBTQ visibility in popular music, both in fiction and nonfiction. This bibliography includes resources about gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender persons involved in the popular music field. The books have all been published in print, and many of them may also be found as e-books. Separate sections contain memoirs, novels, plays, and children’s and teen books. Several LGBT popular music-related DVDs are also listed. Each book and DVD has a link to the OCLC WorldCat record (when available) where you can see which libraries hold the item. Most of this resource is comprised of a discography of popular music recordings by LGBTQ artists. It is not meant to be complete, but many recordings still available in CD format for each artist are listed, and several are annotated. Many of these performers’ songs can now also be found on streaming music services and online digital music websites. -

Somerville, Jimmy (B

Somerville, Jimmy (b. 1961) by Shaun Cole Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Jimmy Somerville. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Courtesy Solar Management Ltd. Noted for his diminutive size and amazing voice, Jimmy Somerville first shot to fame in the mid-1980s as the lead singer with the openly gay pop group of the time, Bronski Beat. Bronski Beat's first single, "Smalltown Boy," which, along with its video, dealt with the problems of being gay in provincial Britain, was an instant success (reaching number three in the UK pop charts) and quickly established the group's reputation. Born in Glasgow on June 22, 1961, Somerville was twenty-three when he formed Bronski Beat in 1984 as a collaboration with Steve Bronski and Larry Stenbachek. The three musicians met while they were working on a video by young gay men and lesbians entitled Famed Youth. It was during this project that Somerville realized that he could sing. Bronski Beat's debut album Age of Consent (1984) included a pink triangle on the cover and listed the age of consent for gay sex in European countries on the inside sleeve as a means of calling attention to the disparity between British and Continental laws at that time. Consisting of a series of songs dealing with various aspects of gay life, the album sold more than a million copies. In 1985 Bronski Beat teamed up with another gay singer, Marc Almond, to record a version of Donna Summer's "I Feel Love," which was also a hit. -

![[ 70/80'S DISCO by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 186 ] 5000 VOLTS >> I'm](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3420/70-80s-disco-by-artist-no-of-tunes-186-5000-volts-im-5053420.webp)

[ 70/80'S DISCO by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 186 ] 5000 VOLTS >> I'm

[ 70/80'S DISCO by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 186 ] 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE A B C >> POISON ARROW ALICIA BRIDGES >> I LOVE THE NIGHT LIFE AMII STEWART >> KNOCK ON WOOD {K} ANDREA TRUE CONVENTION >> MORE MORE MORE ANITA WARD >> RING MY BELL ARROW >> HOT HOT HOT BACCARA >> YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BANANARAMA >> CRUEL SUMMER BANANARAMA >> I WANT YOU BACK {K} BANANARAMA >> NA NA HEY HEY KISS HIM GOODBYE BANANARAMA >> VENUS BARRY MANILOW >> COPACABANA BEE GEES >> JIVE TALKIN' {K} BEE GEES >> NIGHT FEVER {K} BEE GEES >> STAYING ALIVE {K} BEE GEES >> TRAGEDY BEE GEES >> YOU SHOULD BE DANCING {K} BIG FUN >> BLAME IT ON THE BOOGIE BILLY OCEAN >> CARIBBEAN QUEEN BILLY OCEAN >> GET OUTTA MY DREAMS GET INTO MY CAR BILLY OCEAN >> LOVE REALLY HURTS WITHOUT YOU BILLY OCEAN >> LOVERBOY BILLY OCEAN >> WHEN THE GOING GETS TOUGH {K} BLONDIE >> HEART OF GLASS {K} BONEY M >> MA BAKER BOW WOW WOW >> I WANT CANDY BRONSKI BEAT >> HIT THAT PERFECT BEAT BRONSKI BEAT >> WHY BROS >> WHEN WILL I BE FAMOUS BUCKS FIZZ >> MAKING YOUR MIND UP CARL DOUGLAS >> KUNG FU FIGHTING {K} CHANTOOZIES >> WITCH QUEEN CHIC >> DANCE DANCE DANCE CHIC >> LE FREAK {K} CLARENCE CARTER >> STROKIN' COMMUNARDS >> NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE CULTURE CLUB >> CHURCH OF THE POISON MIND CULTURE CLUB >> DO YOU REALLY WANT TO HURT ME CULTURE CLUB >> I'LL TUMBLE 4 YA CULTURE CLUB >> IT'S A MIRACLE CULTURE CLUB >> KARMA CHAMELEON CUT 'N' MOVE >> GIVE IT UP DAN HARTMAN >> INSTANT REPLAY {K} DEBARGE >> RHYTHM OF THE NIGHT DENIECE WILLIAMS >> LET'S HEAR IT FOR THE BOY {K} DEPECHE MODE >> JUST CAN'T GET ENOUGH -

Salisbury, Challenging Macho Values

Challenging Macho Values Challenging Macho Values Practical Ways of Working with Adolescent Boys Jonathan Salisbury David Jackson The Falmer Press (A member of the Taylor & Francis Group) London • Washington, D.C. UK The Falmer Press, 1 Gunpowder Square, London EC4A 3DE USA The Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © J.Salisbury, and D.Jackson, 1996 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from the Publisher. First published in 1996 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available on request ISBN 0-203-39742-8 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-39772-X (Adobe eReader format) ISBN 0 7507 0483 7 cased ISBN 0 7507 0484 5 paper Jacket design by Caroline Archer Contents Acknowledgments vi Acting Hard—A poem by David Jackson viii Preface by Jeff Hearn ix 1 Introduction: Why Should Schools Take Working with Adolescent Boys Seriously? 1 2 The Secondary School as a Gendered Institution 18 3 Boys’ Sexualities 40 4 Sexual Harassment 86 5 Violence and Bullying 104 6 Media Education, Boys and Masculinities 139 7 Language as a Weapon 166 8 The Ideal Manly Body 189 9 School Sport and the Making of Boys and Men 204 10 Boys’ Well-being: Learning to Take Care of Themselves and Others 216 11 How Boys Become Real Lads: Life Stories about the Making of Boys 232 12 Playing War 250 13 Fathers and Sons 274 Bibliography 292 Index 298 v Acknowledgments The authors and publishers would like to thank the following for permission to reproduce materials used in this publication: ‘Smalltown Boy’: Words and Music by Jimmy Somerville, Larry Steinbachek and Steve Bronski © 1994. -

Jimmy Somerville Featuring Bronski Beat and The

Jimmy Somerville The Singles Collection 1984/1990 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: The Singles Collection 1984/1990 Country: Europe Released: 1990 Style: Synth-pop, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1406 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1410 mb WMA version RAR size: 1164 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 604 Other Formats: XM DMF MP2 MIDI DMF MP4 RA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 –Bronski Beat Smalltown Boy 5:09 Don't Leave Me This Way 2 –The Communards 4:32 Vocals – Sarah Jane MorrisWritten-By – Gilbert*, Gamble/Huff* Ain't Necessarily So 3 –Bronski Beat 4:07 Written-By – George & Ira Gershwin To Love Somebody 4 –Jimmy Somerville 4:18 Written-By – Barry Gibb, Robin Gibb Comment Te Dire Adieu 5 –Jimmy Somerville Vocals – June Miles Kingston*Written-By – Arnold Goland, Jack Gold, 3:36 Serge Gainsbourg Run From Love 6 –Jimmy Somerville 3:56 Vocals – Claudia Brücken Never Can Say Goodbye 7 –The Communards 4:27 Written-By – Clifton Davis 8 –Bronski Beat Why? 3:56 9 –The Communards You Are My World 4:30 10 –The Communards For A Friend 4:36 I Feel Love / Johnny Remember Me 11 –Bronski Beat 5:46 Vocals – Marc Almond I Feel Love 11a –Bronski Beat Written-By – Summer*, Moroder*, Bellotte* Johnny Remember Me 11b –Bronski Beat Written-By – Goddard* 12 –The Communards There's More To Love Than Boy Meets Girl 3:51 13 –The Communards So Cold The Night 4:40 You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) 14 –Jimmy Somerville 3:58 Written-By – Dip Warrick*, Sylvester James* 15 –The Communards Tomorrow 4:48 16 –The Communards Disenchanted 4:09 Read My Lips 17 –Jimmy Somerville 4:51 Producer [Additional Production], Mixed By [Mix] – Stephen Hague Companies, etc. -

Interruptions

Curatorial > INTERRUPTIONS INTERRUPTIONS #12 This section proposes a line of programmes devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points Lost Techno-Pop Weekend in Rural Midwestern America of view organised in curatorial series. This mix takes a listen to techno-pop of the seventies and early eighties in a With INTERRUPTIONS we make the most of the vast musical deliberate attempt to vindicate it as one of the most important genres of the last knowledge of the artists and curators involved in the Ràdio century. Web MACBA project, to create a series of ‘breaks’ or ‘interruptions’ in our Curatorial programming. In à-la-carte- music format, our regular curators have carte blanche to 01. Summary create a purely musical experience with only one guiding parameter: the thread that runs through each session must be By the time mainstream pop music really became electronically based in terms of original and surprising. This program takes a listen to synthesizer/sampler instrumentation and editing (first with R&B and hip-hop, techno-pop of the seventies and early eighties as a brief yet then mainstream pop), the techno-pop synth sound would be utterly abandoned deliberate interruption into the realms of pop, rock, soul and by both pop and underground electronic cultures (techno, house, etc.). In this R&B. sense, techno-pop constitutes an isolated and rarely discussed ‘lost weekend’ from standard pop practices. Techno-pop is most often dismissed as a shade of Curated by Terre Thaemlitz new romanticism, punk or electro. However, I believe its strict emphasis on electronics and critical rejection of rock culture (at least in the beginning) make techno-pop in and of itself one of the most important, albeit short-lived, genres of PDF Contents: the last century.