The East Asian Modern Girl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From?

客家 My China Roots & CBA Jamaica An overview of Hakka Migration History: Where are you from? July, 2016 www.mychinaroots.com & www.cbajamaica.com 15 © My China Roots An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From? Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 3 Five Key Hakka Migration Waves............................................................................................. 3 Mapping the Waves ....................................................................................................................... 3 First Wave: 4th Century, “the Five Barbarians,” Jin Dynasty......................................................... 4 Second Wave: 10th Century, Fall of the Tang Dynasty ................................................................. 6 Third Wave: Late 12th & 13th Century, Fall Northern & Southern Song Dynasties ....................... 7 Fourth Wave: 2nd Half 17th Century, Ming-Qing Cataclysm .......................................................... 8 Fifth Wave: 19th – Early 20th Century ............................................................................................. 9 Case Study: Hakka Migration to Jamaica ............................................................................ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 Context for Early Migration: The Coolie Trade........................................................................... -

Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong)

Consumption Voucher Scheme Locations with drop-box for collection of paper registration forms Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Number Location Bank Branch Branch Address 1 HK Shek Tong Tsui Branch Shops 8-12, G/F, Dragonfair Garden, 455-485 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2 HK 188 Des Voeux Road Shop No. 7 on G/F, whole of 1/F - 3/F Branch Golden Centre, 188 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 3 HK Central Branch G/F, 1/F, 2/F and 27/F, Two Chinachem Central, 26 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 4 HK Des Voeux Road Branch Shop G1, G/F & 1/F, Standard Chartered Bank Building, 4-4A Des Voeux Road Central, Central, Hong Kong 5 HK Exchange Square Branch The Forum, Exchange Square, 8 Connaught Place, Central, Hong Kong 6 HK Admiralty Branch Shop C, UG/F, Far East Finance Centre, 16 Harcourt Road, Admiralty, Hong Kong 7 HK Queen's Road East Branch G/F & 1/F, Pak Fook Building, 208-212 Queen's Road East, Wanchai, Hong Kong 8 HK Wanchai Southorn Branch Shop C2, G/F & 1/F to 2/F, Lee Wing Building, 156-162 Hennessy Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong 9 HK Wanchai Great Eagle Shops 113-120, 1/F, Great Eagle Centre, 23 Branch Harbour Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong 10 HK Causeway Bay Branch G/F to 2/F, Yee Wah Mansion, 38-40A Yee Wo Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 11 HK Times Square Priority Whole of Third Floor & Sixth Floor, No. 8 Banking Centre Branch Russell Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 12 HK Happy Valley Branch G/F, 16 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 13 HK North Point Centre Branch Shop G2, G/F, North Point Centre, 278-288 King's Road, -

Our Ref : TP/VAL/Q575/A

For Discussion WCDC Paper On 09.01.2018 No.: 2/2018 Proposed Amendments to the Road Improvement Works at Kennedy Road, and the Junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road, Wan Chai PURPOSE 1. This paper aims to seek Members’ views on the proposed amendments to the Road Improvement Works (“RIW”) following the presentation by the representatives of Hopewell Holdings Limited to Wan Chai District Council on 10 January 2017 regarding the latest development scheme of Hopewell Centre II and the associated RIW amendments. BACKGROUND 2. The original RIW was gazetted in April 2009 and authorized by the Chief Executive in Council in July 2010. The RIW comprises three parts; namely road widening at Kennedy Road, road widening at the junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road, and road widening at the junction of Spring Garden Lane and Queen’s Road East Note 1. Please refer to the Key Plan in 2009 Gazette at Appendix 1. 3. In order to preserve more trees, during the detailed design of the road work, Hopewell Holdings Limited proposed to amend the RIW at Kennedy Road and at the junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road. The proposed amendments to the RIW have been submitted to the relevant Government departments for comment and are considered acceptable in principle. On 11 August 2017, the planning application (No. A/H5/408) of the latest development scheme of Hopewell Centre II was approved with conditions by the Metro Planning Committee of the Town Planning Board including an approval condition on the design and implementation of the related RIW. -

Speech Sound Acquisition of Hong Kong Cantonese a Population

JSLHR Papers in Press. Published May 21, 2012, as doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0080) The final version is at http://jslhr.asha.org. Running Head: Speech Sound Acquisition of Hong Kong Cantonese A population study of children's acquisition of Hong Kong Cantonese consonants, vowels, and tones Carol K. S. To The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR Pamela S. P. Cheung Child Assessment Service, Hong Kong SAR Sharynne McLeod Charles Sturt University, Australia Address for Correspondence: Carol To, Division of Speech and Hearing Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, 5/F Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong SAR. Email: [email protected] Tel: 852-28590591 Fax: 852-25590060 This is an author-produced manuscript that has been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in the Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research (JSLHR). As the “Papers in Press” version of the manuscript, it has not yet undergone copyediting, proofreading, or other quality controls associated with final published articles. As the publisher and copyright holder, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) disclaims any liability resulting from use of inaccurate or misleading data or information contained herein. Further, the authors have disclosed that permission has been obtained for use of any copyrighted material and that, if applicable, conflicts of interest have been noted in the manuscript. 1 Copyright 2012 by The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Abstract Purpose. This study investigated children’s acquisition of Hong Kong Cantonese. Method. Participants were 1,726 children aged 2;4 to11;7. Single-word speech samples were collected to examine four measures: initial consonants, final consonants, vowels/diphthongs, and lexical tones. -

Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’S Experience

C&WDC WG on DC Affairs Paper No. 2/2017 OldOld TTownown CCentralentral 1 Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’s Experience A contemporary lifestyle destination and a chronicle of how Arts, Heritage, Creativity, and Dining & Entertainment evolved in the city Bounded by Wyndham Street, Caine Road, Possession Street and Queen’s Road Central Possession Street Queen’s Road Central Caine Road Wyndham Street Key Campaign Elements DIY Walking Guide Heritage & Art History Integrated Marketing Local & Overseas Publicity Launch Ceremony City Ambience Tour Products 3 5 Thematic ‘Do-It-Yourself’ Routes For visitors to explore the abundant treasure according to their own interests and pace. Heritage & Dining & Art Treasure Hunt All-in-one History Entertainment Possession Street, Tai Ping Shan PoHo, Upper PMQ, Hollywood Graham market & Best picks Street, Lascar Row, Road, Peel Street, around, LKF, from each Man Mo Temple, StauntonS Street & Aberdeen Street SoHo, Ladder Street, around route Tai Kwun 4 Sample route: All-in-one Walking Tour Route for busy visitors 1. Possession Street (History) 1 6: Gough Street & Kau U Fong (Creative & Design – Designer stores, boutiques 2 4: Man Mo Temple Dining – Local food stalls & (Heritage - Declared International cuisine) 2: POHO - Tai Ping Shan Street (Local Monument ) culture – Temples / Stores/ Restaurant) 6 (Art & Entertainment – Galleries / 4 Street Art/ Café ) 3 7 5 7: Pak Tsz Lane Park 5: PMQ (History) 3: YMCA Bridges Street Centre & ( Heritage - 10: Pottinger Ladder Street Arts & Dining – Galleries, Street -

Public Finance Limited – Branch Network

PUBLIC FINANCIAL HOLDINGS LIMITED • ANNUAL REPORT 2006 Public Finance Limited – Branch Network 38 35 36 New Territories 37 34 40 39 33 32 21 20 Kowloon 28 27 19 18 24 23 17 29 25 30 31 22 26 16 15 7 8 11 3 2 14 10 1 6 4 5 9 Hong Kong Island 13 12 4 PUBLIC FINANCIAL HOLDINGS LIMITED • ANNUAL REPORT 2006 Public Finance Limited – Branch Network Hong Kong Island Kowloon New Territories 1 Landmark Branch 15 Star House Branch 32 Kwai Chung Branch Room 1905, Gloucester Tower Basement, Shop B9-B10 Shop 301, 3/F The Landmark, Central Star House Plaza, TST Kwai Chung Plaza Tel: 25224067 Fax: 25373623 Tel: 27308395 Fax: 27302346 7-11 Kwai Foo Road Manager: Rodriguez Lolita H Manager: Ho Mei Yu Denise Tel: 24200121 Fax: 24850590 Manager: Ho Kam Ming 2 Queen’s Road Central Branch 16 Tsimshatsui Branch 1/F, Parker House Shop No. 51-53 33 Tsuen Wan Branch 72 Queen’s Road Central 1/F, Harbour Crystal Centre G/F, 281 Sha Tsui Road Tel: 25266415 Fax: 28779088 100 Granville Road, TST East Tel: 24934187 Fax: 24174497 Manager: Wong Kai Ip Jimmy Tel: 23693236 Fax: 23110433 Manager: Law Shue Sum Dennis Manager: Lai Chung Wai Danny 3 Central Branch 34 Tuen Mun Branch 17 Jordan Road Branch M/F, Chung Nam House Shop 7, G/F, Mei Hang Building Shop B, G/F, Dao Hing Building 59 Des Voeux Road Central Kai Man Path 34 Jordan Road Tel: 25248676 Fax: 28779084 Tel: 24572901 Fax: 24402503 Tel: 27364711 Fax: 23148432 Manager: Leung Kwok Fai Eric Manager: Chan Chiu Ming Peter Manager: Ho Kwok Sin Tom 4 Wing On House Branch 35 Yuen Long Branch Room 1109-10, Wing On House 18 -

Urban Integration & Mass Transit Development in High Density Older

URBD 5710 – Urban Design Studio 1 (Govada, Lau, Paetzold) 27 July 2015 URBAN INTEGRATION & MASS TRANSIT DEVELOPMENT IN HIGH DENSITY OLDER URBAN DISTRICTS: WESTERN DISTRICT, HONG KONG 2015-16 1st Term, Mondays & Thursdays 1.30 – 6.15 pm Instructors: Sujata S. GOVADA (CHEN Yong Ming - Teaching Assistant) M.SC. (URBAN DESIGN) × CUHK Hong Kong is a strategically located, compact city known for its high density development on either side of Victoria harbour with its mountain backdrop, very accessible by its world famous public transit system. It is one of the potential models studied for a more sustainable development of cities in Asia and the region. The attraction of the Hong Kong model is based on its highly compact urban areas, their efficient connection by public transport networks and the con- servation of large land resources as country parks. A central question which policy makers, planners and designers face when considering high-density cities is how livable, walkable and sustainable these cities are and, under conditions of extreme density, how a positive living quality can be achieved. This question is crucial as it is linked with costly and con- troversial long term decisions such as the change of established land use plans, controversial building height restrictions and public space guidelines, as well as plans for urban renewal and new development areas. The views on Hong Kong as a model are strongly divided and reflect contrasting experiences of the city as well as its conflicting values. The 2011 Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranked the Chinese Special Administrative Region on place 70, far behind Vienna (1), Zurich (2), and its main Asian competitor Singapore (25). -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Application for Amendment of Plan Under Section 12A of the Town Planning Ordinance

MPC Paper No. Y/H5/5B For Consideration by the Metro Planning Committee on 13.12.2019 APPLICATION FOR AMENDMENT OF PLAN UNDER SECTION 12A OF THE TOWN PLANNING ORDINANCE APPLICATION NO. Y/H5/5 Applicant Yuba Company Limited represented by AECOM Asia Limited Site 1, 1A, 2 and 3 Hillside Terrace, 55 Ship Street (Nam Koo Terrace), 1- 5 Schooner Street, 53 Ship Street (Miu Kang Terrace) and adjoining Government Land, Wan Chai, Hong Kong Site Area About 2,427.9m2 (including about 300m2 government land) Lease Inland Lot (IL) 2140, IL 1940, IL 2272 & Ext. IL 1564, IL1669, IL 2093 R.P. and IL 2093 s.A R.P. - Standard non-offensive trades clause (IL 2140) - Virtually unrestricted except non-offensive trades clause (the remaining ILs) Plan Draft Wan Chai Outline Zoning Plan (OZP) No. S/H5/27 (at the time of submission of the application) Draft Wan Chai OZP No. S/H5/28 currently in force (the zoning of the site remains unchanged) Zonings “Open Space” (“O”) (84%), “Residential (Group C)” (“R(C)”) (14%) and “Government, Institution or Community” (“G/IC”) (2%) Proposed To rezone the application site from “O”, “R(C)” and “G/IC” to Amendment “Comprehensive Development Area” (“CDA”) 1. The Proposal 1.1 The applicant proposes to rezone the application site (the Site) (Plan Z-1) from “O”, “R(C)” and “G/IC” to “CDA” to facilitate a development which comprises residential and commercial uses and preservation of the Grade 1 historical building of Nam Koo Terrace (NKT). The applicant submitted a Proposed Indicative Scheme in the current application to demonstrate that the proposed land uses and development parameters are acceptable. -

SAP Crystal Reports

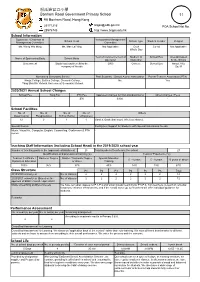

般咸道官立小學 Bonham Road Government Primary School 11 9A Bonham Road, Hong Kong 25171216 [email protected] POA School Net No. 28576743 http://www.brgps.edu.hk School Information Supervisor / Chairman of Incorporated Management School Head School Type Student Gender Religion Management Committee Committee Ms. Wong Wai Ming Ms. Man Lai Ying Not Applicable Gov't Co-ed Not Applicable Whole Day Year of Commencement of Medium of School Bus Area Occupied Name of Sponsoring Body School Motto Operation Instruction by the School Government Study hard and benefit by the 2000 Chinese School Bus About 3765 company of friends Sq. M Nominated Secondary School Past Students' / School Alumni Association Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) King's College, Belilios College, Clementi College, No Yes Tang Shiu Kin Victoria Government Secondary School 2020/2021 Annual School Charges School Fee Tong Fai PTA Fee Approved Charges for Non-standard Items Other Charges / Fees - - $70 $300 - School Facilities No. of No. of No. of No. of Others Classroom(s) Playground(s) School Hall(s) Library(ies) 12 2 1 1 Garden, Basketball court, Wireless intranet. Special Rooms Facility(ies) Support for Students with Special Educational Needs Music, Visual Art, Computer, English, Counselling, Conference & PTA - rooms. Teaching Staff Information (including School Head) in the 2019/2020 school year Number of teaching posts in the approved establishment 25 Total number of teachers in the school 27 Qualifications and professional training (%) Years of Experience (%) Teacher Certificate / Bachelor Degree Master / Doctorate Degree Special Education 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years 10 years or above Diploma in Education or above Training 100% 96% 33% 40% 14% 19% 67% Class Structure P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 Total 2019/2020 school year No. -

The Paradigm of Hakka Women in History

DOI: 10.4312/as.2021.9.1.31-64 31 The Paradigm of Hakka Women in History Sabrina ARDIZZONI* Abstract Hakka studies rely strongly on history and historiography. However, despite the fact that in rural Hakka communities women play a central role, in the main historical sources women are almost absent. They do not appear in genealogy books, if not for their being mothers or wives, although they do appear in some legends, as founders of villages or heroines who distinguished themselves in defending the villages in the absence of men. They appear in modern Hakka historiography—Hakka historiography is a very recent discipline, beginning at the end of the 19th century—for their moral value, not only for adhering to Confucian traditional values, but also for their endorsement of specifically Hakka cultural values. In this paper we will analyse the cultural paradigm that allows women to become part of Hakka history. We will show how ethical values are reflected in Hakka historiography through the reading of the earliest Hakka historians as they depict- ed Hakka women. Grounded on these sources, we will see how the narration of women in Hakka history has developed until the present day. In doing so, it is necessary to deal with some relevant historical features in the construc- tion of Hakka group awareness, namely migration, education, and women narratives, as a pivotal foundation of Hakka collective social and individual consciousness. Keywords: Hakka studies, Hakka woman, women practices, West Fujian Paradigma žensk Hakka v zgodovini Izvleček Študije skupnosti Hakka se močno opirajo na zgodovino in zgodovinopisje.