Westminsterresearch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on The

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on the Application filed before the International Court of Justice by the Cooperative of Guyana on March 29th, 2018 ANNEX Table of Contents I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and process of decolonization of the British Guyana, 1961-1965 ................................................................... 3 II. London Conference, December 9th-10th, 1965………………………15 III. Geneva Conference, February 16th-17th, 1966………………………20 IV. Intervention of Minister Iribarren Borges on the Geneva Agreement at the National Congress, March 17th, 1966……………………………25 V. The recognition of Guyana by Venezuela, May 1966 ........................ 37 VI. Mixed Commission, 1966-1970 .......................................................... 41 VII. The Protocol of Port of Spain, 1970-1982 .......................................... 49 VIII. Reactivation of the Geneva Agreement: election of means of settlement by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, 1982-198371 IX. The choice of Good Offices, 1983-1989 ............................................. 83 X. The process of Good Offices, 1989-2014 ........................................... 87 XI. Work Plan Proposal: Process of good offices in the border dispute between Guyana and Venezuela, 2013 ............................................. 116 XII. Events leading to the communiqué of the UN Secretary-General of January 30th, 2018 (2014-2018) ....................................................... 118 2 I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and Process of decolonization -

Bermuda Insurance Quarterly

20333E_BIQ.qxp:.ps 6/24/09 4:51 PM Page 1 ALL THE RESULTS & ANALYSIS Q1 12 BERMUDA BIQJuly 2009 ‘TAX HAVEN’ BERMUDA LATEST 10 INSURANCE QUARTERLY HAIR TODAY © 2009 Bermuda Media … BUT THEN in association with IT’S GONE! 20 Flagstone Re and ACE have already moved their headquarters from Bermuda to Switzerland. With others likely to follow, why is Switzerland an attractive LURE OF THE ALPS… proposition for a growing number of Bermudian companies? See page 4 20333E_BIQ.qxp:.ps 6/24/09 4:19 PM Page 2 Invest with people who are invested in you. The trust and relationships we build with each of our clients enable us to provide a complete array of private banking services with truly personal service. From investments to trusts, we offer comprehensive integrated wealth management services with the greatest degree of expertise on the island. Backed by a strong and risk averse portfolio. The experience, talent and knowledge of our Private Banking team is dedicated to protecting and growing your assets. For personalized advice and service, contact: Barbara R Tannock, CFA Head of Private Banking 294.5174 [email protected] 19 Reid Street | 296.6969 | capital-g.com Welcome to the family. 20333E_BIQ.qxp:.ps 6/24/09 4:52 PM Page 1 THE QUOTES OF THE QUARTER “As the year goes on I expect “While we have seen the BIQ revenue growth to remain green shoots of recovery, we under pressure due to global do not believe the risk-reward BERMUDA INSURANCE recessionary conditions and characteristics have sufficient- foreign exchange. -

Report of the Commission of Inquiry Appointed to Inquire And

REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY APPOINTED TO ENQUIRE AND REPORT ON THE CIRCUMSTANCES SURROUNDING THE DEATH IN AN EXPLOSION OF THE LATE DR. WALTER RODNEY ON THIRTEENTH DAY OF JUNE, ONE THOUSAND NINE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY AT GEORETOWN VOLUME 1: REPORT AND APPENDICES FEBRUARY 2016 Transmittal Letter Chapter 6 Contents Chapter 7 Table of Contents Chapter 8 Chapter 1 Chapter 9 Chapter 2 Tendered Exhibits Chapter 3 Procedural Rules Chapter 4 Correspondence Chapter 5 Editorial Note 1 2 Transmittal of Report of the Commission of Inquiry to enquire into and report on the circumstances surrounding the death in an explosion of the late Dr. Walter Rodney on the thirteenth day of June one thousand nine hundred and eighty at Georgetown To His Excellency David A. Granger President of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana Your Excellency, In my capacity as Chairman of the Walter Rodney Commission of Inquiry, I have the honour to submit the Report of the Inquiry to which the President appointed us by Instrument dated 8th February, 2014. The Commissioners were, in the Instrument of Appointment, expected to submit their Report within ten (10) weeks from the start of the Commission. The Commission started its work on 28th April, 2014. As we understand it, the premise informing the early submission date was that the Commission coming thirty-four (34) years after the death of Dr. Walter Rodney and the events surrounding that event, would, in all probability, be supported by only a few persons volunteering to give evidence and/or having an interest in this matter. -

Border Crossing Brothas: a Study of Black Bermudian Masculinity, Success, and the Role of Community-Based Pedagogical Spaces

DOUGLAS, TY-RON MICHAEL O’SHEA, Ph.D. Border Crossing Brothas: A Study of Black Bermudian Masculinity, Success, and the Role of Community-based Pedagogical Spaces. (2012) Directed by Dr. Camille M. Wilson. 289 pp. Using qualitative research methods and an amalgamation of border crossing theory and postcolonial theory within the context of race, this dissertation study examined how Black Bermudian males form identities, define success, and utilize community-based pedagogical spaces (i.e. barbershops, churches, sports/social clubs, neighborhoods) to cross literal and figurative borders. Drawing on data from 12 Bermudian Black males who were active participants in community spaces, this study challenges educators to consider how the disturbing statistics on Black male failure and the perceived achievement gap between White students and students of color may be influenced by tensions between dominant ideologies of success, the under appreciation of community-based pedagogical spaces by educational stakeholders, and competing conceptualizations of identity, success, and masculinity for Black males. BORDER CROSSING BROTHAS: A STUDY OF BLACK BERMUDIAN MASCULINITY, SUCCESS, AND THE ROLE OF COMMUNITY-BASED PEDAGOGICAL SPACES by Ty-Ron Michael O’Shea Douglas A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2012 Approved by Committee Chair © 2012 Ty-Ron Michael O’Shea Douglas To the memories of Ivy “Ma” Richardson, “Granny Mary” Wilkinson, Henry “Papa” Thomas, Louise “Nana Louise” Jackson, Bernard “Uncle Jack” Jackson, Mandell “Hillside” Hill, Mother Burruss, and Ronald Burruss—men and women whose lives, legacies, and love inspired me to be a border crosser and bridge across time and space. -

Jamaica Ready for a Change… Or Not? Last Month Grenadian-Born ~ Jamaicans Go to the Polls Shalrie Joseph Was Selected This Month to Decide Whether to to Captain U.S

CTAugust07.qxd 8/9/07 12:17 PM Page 1 PRESORTED AUGUST 2007 STANDARD ® U.S. POSTAGE PAID MIAMI, FL PERMIT NO. 7315 Tel: (305) 238-2868 1-800-605-7516 [email protected] [email protected] W e cover your world Vol. 18 No. 9 Jamaica: 654-7282 THE MULTI AWARD-WINNING NEWS MAGAZINE ~ Dr. Annmarie Mykal Fax, left, and Steve Barnes and other McAlpin are young Caribbean-born filmmakers representatives with a new movie out and big from the ambitions to break into the Caribbean are mainstream of a very tough appealing to what business, page 15. some see as an ‘out of step’ United States for leniency on its deportation policy, page 2. It’s back-to-school time again after the long summer holidays and parents, as well as chil- dren, must gear up for the new year. Caribbean Today offers a special feature, pages 18-21. Jamaica ready for a change… or not? Last month Grenadian-born ~ Jamaicans go to the polls Shalrie Joseph was selected this month to decide whether to to captain U.S. Major League continue with Portia Simpson Soccer’s All-Star team, a big Miller, left, and the PNP, which honor for the New England Revolution star. But the mid- has ruled the country for 18 years, fielder has his eyes on a much or change course with the JLP bigger prize, page 26. Simpson Millerled by Bruce Golding, page 7. Golding CALL CARIBBEAN TODAY DIRECT FROM JAMAICA 654-7282 INSIDEINSIDE News . .2 Food . .12 Back To School Feature . .18 Tourism/Travel . -

Bermuda House of Assembly and Senate Special Joint Sitting

BERMUDA HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY AND SENATE SPECIAL JOINT SITTING IN HONOUR OF THE LATE CHARLES WALTON DE VERE BROWN, JR., JP, MP HANSARD 11 OCTOBER 2019 Official Hansard Report 11 October 2019 1 BERMUDA HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY AND SENATE SPECIAL JOINT SITTING IN HONOUR OF THE LATE CHARLES WALTON DE VERE BROWN, JR., JP, MP 11 OCTOBER 2019 10:11 AM [Hon. Derrick V. Burgess, Sr., Deputy Speaker, in the Although soft-spoken at most times, Walton was able Chair] to convince the inconvincible that Bermuda would not be able to reach its full potential until the Union Jack PRAYERS was lowered and Bermuda’s own flag was hoisted. W. E. B. Du Bois, a prolific and influential Af- [Prayers read by Mrs. Shernette Wolffe, Clerk] rican American scholar and activist, said, “The cost of liberty is less than the price of repression.” It is a well- ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER known fact that Walton’s fervent desire for an inde- OR MEMBER PRESIDING pendent Bermuda was evident in the many speeches he made on the floor of the House of Assembly and in the community as a whole. APOLOGIES None of us were surprised when Brother Wal- ton was appointed to the Senate in 2007 by his cousin Good morning. There are two The Deputy Speaker: and party colleague, the Honourable Dr. Ewart Brown. Members who are absent today: the Honourable After all, Walton had paid his dues by serving the par- Speaker, Dennis Lister, [Jr.]; and the Honourable ty in various capacities since 1983 when he returned Member Cole Simons. -

Kiyemba FINAL Merits Brief.DOC

No. 08-1234 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States JAMAL KIYEMBA, et al., Petitioners, v. BARACK H. OBAMA, et al., Respondents. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT BRIEF OF PETITIONERS Eric A. Tirschwell Sabin Willett Michael J. Sternhell Counsel of Record Darren LaVerne Rheba Rutkowski Seema Saifee Neil McGaraghan KRAMER LEVIN NAFTALIS Jason S. Pinney & FRANKEL LLP BINGHAM MCCUTCHEN LLP 1177 Avenue of the Americas One Federal Street New York, New York 10036 Boston, Massachusetts 02110 Elizabeth P. Gilson (617) 951-8000 383 Orange Street Susan Baker Manning New Haven, CT 06511 BINGHAM MCCUTCHEN LLP J. Wells Dixon 2020 K Street, N.W. CENTER FOR CONST. RIGHTS Washington, D.C. 20036 666 Broadway, 7th Floor George Clarke New York, New York 10012 MILLER & CHEVALIER CHTD Angela C. Vigil 655 15th St., N.W., Ste. 900 BAKER & MCKENZIE LLP Washington, D.C. 20005 Mellon Financial Center Clive Stafford Smith 1111 Brickell Ave., Ste. 1700 REPRIEVE Miami, Florida 33131 P.O. Box 52742 Counsel to Petitioners London EC4P 4WS i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether a federal court exercising its habeas juris- diction, as confirmed by Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. __, 128 S. Ct. 2229 (2008), has no power to order the release of prisoners held by the Executive for seven years in the Guantánamo prison, where the Executive detention is indefinite and without authorization in law, and release in the continental United States is the only possible effective remedy. ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Seventeen petitioners brought this appeal, seeking reinstatement of the release order issued by the district court in October, 2008. -

The Bermuda Society

The Bermuda Society Autumn/Winter 2010 Newsletter – Issue 13 IN THIS ISSUE O New Chairman O Aon Benfield Research Lloyd’s Update – 2010 Interim results and Outlook for 2011 The Aon Benfield Aggregate – 9M 2010 Aon Benfield’s Reinsurance Market Outlook – January 2011 O Solvency II O Basel III O Society Events Mr Bradford Kopp’s Speech O Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences Sir Crispin Tickell’s Speech Dr Tony Knap’s Speech O Bermuda National Trust O The Bermuda Society – Summer Internship Programme New Chairman Aon Benfield’s Reinsurance Market Robert Childs, Chief Underwriting Officer, Hiscox Outlook – January 2011 plc and Chairman of Hiscox USA Aon Benfield’s 2011 Reinsurance Market Outlook – The Chairmanship of The Bermuda Society passes from Dr Partnership Renewed – released 30 December – reviews the James King to Robert Childs with Raymond Sykes trends experienced at the January 01 reinsurance renewals remaining as Deputy Chairman. and analyses specific challenges facing insurers and reinsurers in the year ahead. Property catastrophe Upon his return to London from Bermuda, Robert was expectations are discussed for upcoming U.S. property appointed to the Society’s Committee of Management in catastrophe renewals. March 2009 and was elected Chairman in November 2010. The report contains updates by individual business line and Robert joined Hiscox in 1986; served at the Active region, and also focuses on key topical issues for global Underwriter of the Hiscox Lloyd’s Syndicate 33 between 1993 (re)insurers that have an impact on reinsurance supply, and 2005; and is the Group’s Chief Underwriting Officer. demand and pricing. -

PLP 2007 Platform

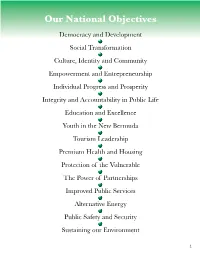

Our National Objectives Democracy and Development Social Transformation Culture, Identity and Community Empowerment and Entrepreneurship Individual Progress and Prosperity Integrity and Accountability in Public Life Education and Excellence Youth in the New Bermuda Tourism Leadership Premium Health and Housing Protection of the Vulnerable The Power of Partnerships Improved Public Services Alternative Energy Public Safety and Security Sustaining our Environment 1 Message from the Leader Dr. The Hon. Ewart Brown “We have learnt the art and science of government and we conscientiously practice it to the greatest good of the greatest number of the Bermudian people. Bermuda is on the right track and heading in the right direction under the PLP. We intend to increase the momentum, and that we shall do.” Fellow Bermudians, Bermuda goes to the polls on in the right direction under the 1998 print advertisement with Tuesday, December 18 in an PLP. We intend to increase the a dreadlocked PLP officer and election that will be pivotal to momentum, and that we shall. candidate lined up in the cross our country’s future. Patterns hairs of a sniper’s rifle, wins the of Progress, the PLP Election The choices facing the electorate Piety Award when compared to Manifesto, offers ample bases are to continue to progress with the editorial assault of this cam- on which to decide your choice the PLP or to go back to the past paign of 2007; and the savage in the General Election. Our under the UBP. Because of the smut that is circulated by viral platform has emerged from the horror of forgetfulness, there are email. -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Annual Report 1999

('r • ) t Ministry of Foreign Affairs • "Service within and beyond our borders" • • .. Annual Report 1999 • • ~ · ,. ./ . TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Mission Statement ................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 4 Department of Americas and Asia ........................................................................ 7 Economic Affairs Department ............................................................................. 20 Multilateral and Global Affairs Department .. ............................................ ............. 35 Minister's Secretariat ..................................................................... ... .................. 46 Public Affairs and Information Unit .................. ................. ........................ ......... ... 57 Administration and Finance Department .. .. ........... .......... .................................. .. 59 Protocol and Consular Affairs Department .......................................................... 61 Guyana Embassy - Beijing .................................................................................. 64 Guyana Embassy- Brasilia ............................................ .......... ........................... 71 Guyana Embassy - Brussels ............. .............................. ........................ ....... ...... 88 Guyana Embassy - Caracas ........................................................ -

International Court of Justice

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE WHITE PAPER OF THE VENEZUELAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS (COVRI) REGARDING THE PENDING CASE ARBITRAL AWARD OF 3 OCTOBER 1899 (GUYANA v. VENEZUELA) STATEMENT OF FACTS, JURISDICTION AND ADMISSIBILITY sent to the Registry of the Court on 9 December 2020 prepared by Dr. Kenneth Ramírez _________________ COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE LIVRE BLANC DU CONSEIL VÉNÉZUÉLIEN POUR LES RELATIONS INTERNATIONALES (COVRI) CONCERNANT L’AFFAIRE PENDANT SENTENCE ARBITRALE DU 3 OCTOBRE 1899 (GUYANA c. VENEZUELA) EXPOSÉ DES FAITS, COMPÉTENCE ET RECEVABILITÉ envoyé au Greffe de la Cour le 9 décembre 2020 preparé par Dr. Kenneth Ramírez TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction...............................................................................................4 II. Statement of Facts: the Null and Void 1899 Award................................15 A. Historical Rights and Legal Titles of Venezuela................................15 B. Origins of the Dispute........................................................................27 C. Vices of the 1897 Arbitration Treaty..................................................30 D. Grounds of Nullity of 1899 Award......................................................40 E. Venezuelan always protested the 1899 Award and was not estopped to denounce the nullity of it................................................................73 III. Statement of Facts: the 1966 Geneva Agreement and its implementation until 2018................................................................................................97 -

2020 Summit Address by Mr

The Bermuda Construction Safety Council Police Headquarters 2020 Summit Address By Mr. Brendon Harris Safety Coordinator June 2020 To his Excellency the Governor John Rankin, the Honourable Premier David Burt, the Minister of Safety Wayne Caine’s and the Commissioner of Police Stephen Corbishley. We meet today to consider questions, of great moment. Covid 19 has demonstrated to the world its aggressive intentions. It has already infected Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. On top of that it has reached our shores and claimed the lives of our very own citizens. Furthermore, overseas racial tensions have erupted from peaceful to violent protests. Simultaneously we are here preparing for an upcoming global recession. All while facing the beginning of a hurricane season. Councilwoman, I believe these are all just causes for our Summit.I refer to: Section 1 of the Constitution.Whereas every person in Bermuda is entitled to the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual, that is to say, has the right, whatever his race, place of origin, political opinions, colour, creed or sex, but subject to respect for the rights and freedoms of others and for the public interest, to each and all of the following, namely: life, liberty, security of the person and the protection of the law; freedom of conscience, of expression and of assembly and association; and protection for the privacy of his home and other property and from deprivation of property without compensation. As part of our National self identity it is imperative that we continue communicating with each other, educating our selves and assessing the risks involved with our health and safety and our environment.