Academic Clustering: a Longitudinal Analysis of a Division I Football Program ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Review Summer 2015 Alumni Association of the University of the Pacific

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons Pacific Review University of the Pacific ubP lications Summer 6-1-2015 Pacific Review Summer 2015 Alumni Association of the University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pacific-review Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Alumni Association of the University of the Pacific, "Pacific Review Summer 2015" (2015). Pacific Review. 3. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pacific-review/3 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University of the Pacific ubP lications at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pacific Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFIC’S PACIFIC ALUMNI MAGAZINE | SUMMER 2015 REVIEW Moscone A Tribute George R. George COACH PETE CARROLL ’73, ’78: SECRETS TO SUCCESS | FAREWELL TO “THE GREATEST TIGER OF THEM ALL” Courtney Bye Says Hello to Washington, D.C. Pacifi c’s fi rst-ever Nathan Scholar gets unparalleled experience in the world of economics Courtney Bye ’16 is an economics enthusiast and a standout student in the classroom. However, she knows that following her passion to become successful in today’s fast-paced fi eld of global economic development requires much more than just textbook smarts. Thanks to the newly established Nathan Scholars program, Courtney will gain real-world experience this summer through an internship at a top international economics consulting fi rm, Nathan Associates Inc. Courtney is one of the fi rst students to be named a Nathan Scholar, a distinction made possible by the support of the fi rm’s chairman Dr. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

1 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968

1 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 5 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 7 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 8 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 9 Imagine John Lennon 1971 10 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 11 Born In The USA Bruce Springsteen 1985 12 Happy Together The Turtles 1967 13 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 14 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 15 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 16 I Heard It Through The Grapevine Marvin Gaye 1968 17 American Pie Don McLean 1972 18 Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival 1969 19 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 20 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 21 Light My Fire The Doors 1967 22 My Girl The Temptations 1965 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 California Girls Beach Boys 1965 25 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 1968 26 Take It Easy The Eagles 1972 27 Sherry Four Seasons 1962 28 Stop! In The Name Of Love The Supremes 1965 29 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 30 Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley 1956 31 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 32 Louie Louie The Kingsmen 1964 33 Still The Same Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1978 34 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 35 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 36 Tears Of A Clown Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 1970 37 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer 1986 38 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 39 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 40 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 41 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 42 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 43 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 44 Old Time Rock And Roll Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1979 45 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 46 Jump (For My Love) Pointer Sisters 1984 47 Little Darlin' The Diamonds 1957 48 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 49 Night Moves Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1977 50 Oh, Pretty Woman Roy Orbison 1964 51 Ticket To Ride The Beatles 1965 52 Lady Styx 1975 53 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 54 L.A. -

50S 60S 70S.Txt 10Cc - I'm NOT in LOVE 10Cc - the THINGS WE DO for LOVE

50s 60s 70s.txt 10cc - I'M NOT IN LOVE 10cc - THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE A TASTE OF HONEY - OOGIE OOGIE OOGIE ABBA - DANCING QUEEN ABBA - FERNANDO ABBA - I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA - KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA - MAMMA MIA ABBA - SOS ABBA - TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA - THE NAME OF THE GAME ABBA - WATERLOU AC/DC - HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC - YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE - HOW LONG ADRESSI BROTHERS - WE'VE GOT TO GET IT ON AGAIN AEROSMITH - BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH - COME TOGETHER AEROSMITH - DREAM ON AEROSMITH - LAST CHILD AEROSMITH - SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH - WALK THIS WAY ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DAMNED IF I DO ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DOCTOR TAR AND PROFESSOR FETHER ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - I WOULDNT WANT TO BE LIKE YOU ALBERT, MORRIS - FEELINGS ALIVE N KICKIN - TIGHTER TIGHTER ALLMAN BROTHERS - JESSICA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MELISSA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALLMAN BROTHERS - RAMBLIN MAN ALLMAN BROTHERS - REVIVAL ALLMAN BROTHERS - SOUTHBOUND ALLMAN BROTHERS - WHIPPING POST ALLMAN, GREG - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALPERT, HERB - RISE AMAZING RHYTHM ACES - THIRD RATE ROMANCE AMBROSIA - BIGGEST PART OF ME AMBROSIA - HOLDING ON TO YESTERDAY AMBROSIA - HOW MUCH I FEEL AMBROSIA - YOU'RE THE ONLY WOMAN AMERICA - DAISY JANE AMERICA - HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA - I NEED YOU AMERICA - LONELY PEOPLE AMERICA - SISTER GOLDEN HAIR AMERICA - TIN MAN Page 1 50s 60s 70s.txt AMERICA - VENTURA HIGHWAY ANDERSON, LYNN - ROSE GARDEN ANDREA TRUE CONNECTION - MORE MORE MORE ANKA, PAUL - HAVING MY BABY APOLLO 100 - JOY ARGENT - HOLD YOUR HEAD UP ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - DO IT OR DIE ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - IMAGINARY LOVER ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - SO IN TO YOU AVALON, FRANKIE - VENUS AVERAGE WHITE BD - CUT THE CAKE AVERAGE WHITE BD - PICK UP THE PIECES B.T. -

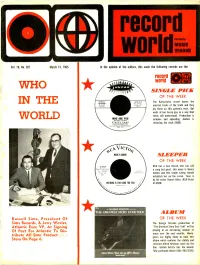

In Theopinion of Theeditors, This Week the Following Records Are The

record Formerly MUSIC worldVENDOR Vol. 19, No. 927 March 13, 1965 In theopinion of theeditors, this week the following records are the recordroll/1 world J F1,4 WHO SINGLE PICK OF THE WEEK RECORDNO. VOCAL Will. The Kama -Sutracrowdknowsthe 45-5500 iRST ACCOMP IN THE rill 12147) MAGGIE MUSS. TIME 2.06 (OW) musical tricks of the trade and they ply them on this galvanic rock.Gal wails at her bossy guy in a way that teens will understand.Production is WHO ARE YOU complexandappealing.Jubileeis WORLD (Chi Taylor-Ted Oaryll) STACEY CANE By GARY SHERMAN releasing the deck (5500). KAMA-SUTRA PRODUCTIONS pr HY MIIRAHI-PHI( STFINPERc ARTIE RIP,' NVICro#e NANCY ADAMS SLEEPER OF THE WEEK 47-8529 RCA has a new thrush who can sell Omer Productions, a song but good. Her name is Nancy Inc.,ASCAP SPHIA-1938 Adams and this single outing should 2:31 establish her on the scene. Tune is by hit writer Robert Allen. (RCA Victor NOTHING IS TOO GOOD FOR YOU 47.8529) Slew, GEORGE STEVENS THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD ALBUM Russell Sims, President Of OF THE WEEK Sims Records, & Jerry Wexler, TheGeorgeStevensproductionof Atlantic Exec VP, At Signing "The Greatest Story Ever Told" will be Of Pact For Atlantic To Dis- playinginan increasing number of areas over the next months.Movie- ... tribute All Sims Product. goers are highly likely to want this Story On Page 6. album which contains the stately and reverant Alfred Newman score for the film.United Artists has the beauti- fully packaged album (UAL/JAS 5120). -

Episode 6: Drazen Petrovic and Basketball’S Cold War

Death at the Wing Episode 6: Drazen Petrovic and Basketball’s Cold War ⧫ ⧫ ⧫ Back in 1988, the USA Men’s Basketball team did something they almost never did... ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: The United States found themselves in a position in the last seven minutes of this game of having to score on almost every possession and they could not. After winning 9 of the last 10 Olympics they competed in, they lost. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: But there’s no time, really, for even a miracle now. And the Soviets are already celebrating. The USA suddenly found itself wearing bronze. It did not go over well. And so, as the dust settled, they decided to do what America does best: get better through hard work, inch by inch, grinding it out… I’m kidding. No, we did the real American thing. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: What may well be the best basketball team ever assembled… ...which is throwing lots of money at something to make even more money. And so, for the next Olympics, they formed a super squad of sorts. No more amateurs. It was time to bend the rules a little bit and bring in the pros. And, of course, bring in Reebok to sponsor it. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: And now, the United States of America. This was the Dream Team. Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Michael Jordan. This wasn’t about winning gold. This was about buying the whole fucking gold mine. Shock and awe. 1 But in Barcelona in 1992, one player in all of the Olympics didn’t get the memo... or fax. -

1 Dreamboats, Boybands and the Perils of Showbiz: Pop and Film, 1956-1968 David Buckingham This Essay Is Part of a Larger Projec

Dreamboats, Boybands and the Perils of Showbiz: Pop and Film, 1956-1968 David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. The first appearance of rock and roll music in film seems to have been something of an afterthought. When Richard Brooks’s Blackboard Jungle was released in 1955, the producers made a last-minute decision to accompany the opening and closing credits with an obscure B-side called ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and the Comets. The record had been released the previous year with little success. Although an instrumental version of the tune does appear in the middle of the film, Blackboard Jungle is barely concerned with rock or pop music at all. In one notable scene, the delinquent teenagers trash their teacher’s treasured collection of jazz records; while in another, one of the students, Gregory Miller (played by Sidney Poitier) performs a gospel song with his black class-mates. However, the inclusion of Haley’s track made it an immediate chart hit; and it also contributed to the remarkable success of the film with teenage audiences. Indeed, the use of ‘Rock Around the Clock’ seems to have encouraged dancing and even wilder behaviour in cinemas, both in the US and in the UK. When the film was shown in South London in 1956, Teddy Boys in the audience reportedly rioted and slashed the seats; and this led to similar behaviour in cinemas around the country. -

Mustang Daily, April 23, 1971

A u---I W r—n ArchlTfiM o ♦— its i l . o “•••THEM 1 / » 0 0 LETlOOft, NOT ThEOTl TO If efCALLft" o QI x s 9 U_I | C— U — l I r—n r—n 5 oU---I l r—n of r—n LJ--- / UI Q o l — t U—l o o r—n i—no u —i o| r—n o l § Vol. XXXIII No. 100 •an Lula Obispo. California Friday, April 23, 1071 SPECIAL EDITION POLY ROYAL ’71 can ideas be conceived, formed startling color. The ideas are the suggest any double or triple What’s it all about? and implemented as forcefully as best—perfect and outstanding— meaning with the word spring, in a college? the egg can offer. there are several possible ap by John Trumbo and life, and the expression of The egg is symbolic of the In relating the egg and but plications. Poly Royal is a Spring activity; the butterflies are Just what kind of poster Is It? new, dynamic ideas as forces college community. Even more, terflies to the quote from ^ringing forth from the egg and "It Is a thinking man's poster, released to change the world it represents all life, says Parkinson, it is obvious that if the butterflies commonly appear and to me should be very easily were the kind of thoughts he was Reynolds. From within the egg butterflies do Indeed break out of during the Spring. understood," says the creator ot trying to congeal. Then he found the ideas, fully developed as the egg, the egg, like Humpty- The poster certainly is an at the much misunderstood Poly a quote from the philosopher adult butterflies, break out into Dumpty, cannot be put together Royal 71 poster. -

2012 Louisiana Tech Football Game Notes 52 All-Americans 25 Conference Championships 2 National Titles

2012 LOUISIANA TECH FOOTBALL GAME NOTES 52 ALL-AMERICANS 25 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS 2 NATIONAL TITLES GAME INFORMATION Date/Time: Saturday, Oct. 6 / 6 p.m. CT GAME 5 RV/RV LOUISIANA TECH (4-0, 0-0 WAC) vs. UNLV (1-4, 1-0 MWC) Site: Ruston, La. / Joe Aillet Stadium (30,600) Oct. 6, 2012 l 6 p.m. CT l TV: ERT l Radio: LA Tech Sports Network TV: ESPN Regional (ERT) Talent: Trey Bender (PxP), Jay Taylor (Analyst), Ruston, La. l Joe Aillet Stadium (30,600) Radio: LA Tech Sports Network (Flagship: KXKZ 107.5 FM) Talent: Dave Nitz (PxP), Teddy Allen (Analyst), THE GAME Max Causey (Sideline) Louisiana Tech (4-0) returns to Louisiana to host three consecutive home games for the first time Live Stats/GameTracker: LATechSports.com since 1997 starting with an Oct. 6 match-up against UNLV (1-4). Tech, with its hottest start since 1975, Twitter Updates: @LATechFB gets a brief reprieve in giant slaying for a week as the improving Rebels visit Joe Aillet Stadium for just the Series: UNLV leads, 2-0 second time ever, the first since 1993. Ruston: UNLV leads, 1-0 Las Vegas: UNLV leads, 1-0 First Meeting: UNLV, 28-23, Nov. 6, 1993 THE COACHES Last Meeting: UNLV, 24-20, Oct. 8, 1994 Louisiana Tech: Sonny Dykes is in his third year at Louisiana Tech and overall as a head coach. He Streak: UNLV, 2 has a 17-12 record overall and led the Bulldogs to a 2011 WAC Championship and Poinsettia Bowl appear- ance last year. -

An Owner's Game

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 63 Issue 2 Article 8 April 2019 An Owner's Game Marc Lasry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Marc Lasry, An Owner's Game, 63 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. 285 (2018-2019). This Getting an Edge: A Jurisprudence of Sport is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 63 | 2018/19 VOLUME 63 | 2018/19 MARC LASRY An Owner’s Game 63 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 285 (2018–2019) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Marc Lasry ’84 founded and acts as CEO of Avenue Capital, a leading distressed securities hedge fund. In 2014, Marc became the principal co-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks of the National Basketball Association. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review 285 AN OWNER’S GAME I. AMATEURS AND PROFESSIONALS Robert Blecker1: We can distinguish amateurs from professionals not by whether they get paid, but rather by what really motivates them. Thus, an amateur athlete might be highly paid, yet still compete for the love of the game or sport. On the other hand, if an athlete does it for the money, fame, prestige, or any other extrinsic reward, that athlete really can’t qualify as an amateur. Are some team owners in it for the money, and money only? And other owners in it for other reasons? If so, what are they? And which type of owner are you? Marc Lasry: Oh, I love the game. -

The British Invasion: Finding Traction in America by Piacentino Vona A

The British Invasion: Finding Traction in America by Piacentino Vona A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Piacentino Vona 2018 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract As a period of American History, the 1960s has provided historians and academics with a wealth of material for research and scholarship. Presidents John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon, the Vietnam War, the hippie era, and the Civil Rights Movement, among other topics have received thorough historical discussion and debate. Music was another key aspect in understanding the social history of the 1960s. But unlike the people and events mentioned above, historians have devoted less attention to music in the historical landscape. The British Invasion was one such key event that impacted America in the 1960s. Bands such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Who found their way into the United States and majorly impacted American society. Using secondary sources, newspaper articles, interviews and documentaries on these bands, this thesis explores the British Invasion and its influence in the context of 1960s America. This thesis explores multiple bands that came in the initial wave. It follows these bands from 1964-1969, and argues that the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Who shared common multiple factors that allowed them to attain the traction to succeed and to maintain that success in the United States. -

45 Collection

TYPE ARTIST HIT FLIP LABEL NO CON VALUE RR 1910 FRUITGUM COMPNY SIMON SAYS BUDDAH 024 V $2.00 RR 1910 FRUITGUM COMPNY MR JENSEN GIANT STEP BUDDAH 039 N $8.00 RR 1910 FRUITGUM COMPNY 1 2 3 RED LIGHT STICKY STICKY BUDDAH 054 E $7.00 RR 1910 FRUITGUM COMPNY GOODY GOODY GUMDROP CANDY KISSES BUDDAH 071 N $8.00 RR 1910 FRUITGUM COMPNY INDIAN GIVER POW WOW BUDDAH 091 N $8.00 RR 1910 FRUITGUM COMPNY SPECIAL DELIVERY NO GOOD ANNIE BUDDAH 114 N $8.00 RR 3-D’S NOTHIN TO WEAR HAPPIEST BOY AND GIRL BRUNS 55152 E $10.00 5 BLIND BOYS MONTANA BROTHER BILL RI FILED UNDER SPARKTONES VINTGE 1000 N $2.00 COM A PAIR OF KINGS ONCE MONSTER RCA 7659 E RR ABBOTT BILLY COME ON AND DANCE WITH ME GROOVY BABY PARKWY 874 N $20.00 DWP ACADEMICS GIRL THAT I LOVE I OFTEN WONDER (RED) ANCHO 104 N $5.00 DWP ACADEMICS AT MY FRONT DOOR (RED) DARLA MY DARLIN’ RELIC 509 G $3.00 RR ACCENTS WIGGLE WIGGLE DREAMIN’ AND SCHEMIN’ BRUNS 55100 N $25.00 RR ACCENTS CHING A LING I GIVE MY HEART TO YOU BRUNS 55123 E $25.00 RB ACE BUDDY BEYOND THE RAINBOW ANGEL BOY DJ DUKE 199 N $30.00 RB ACE BUDDY WONT YOU RECONSIDER THIS LITTLE LOVE OF MINE DUKE 325 V $10.00 RB ACE JOHNNY CROSS MY HEART ANGEL DUKE 107 N $50.00 RB ACE JOHNNY PLEASE FORGIVE ME YOUVE BEEN GONE TOO LONG DUKE 128 N $50.00 RB ACE JOHNNY PLEDGING MY LOVE ANYMORE DUKE 136 N $30.00 RB ACE JOHNNY PLEDGING MY LOVE NO MONEY DUKE 136 N $50.00 RB ACE JOHNNY ANYMORE HOW CAN YOU BE SO MEAN DUKE 144 E $40.00 RB ACE JOHNNY I STILL LOVE YOU SO DONT YOU KNOW DUKE 154 V $10.00 RB ACE JOHNNY SAVING MY LOVE FOR YOU+ ANGEL/PLEASE FORGIVE ME