Chapter1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soup Recipes Index

Soup Soup Recipes Index ● Chowders : INDEX ● ``Cream of'' Soups : INDEX ● Hot and Sour Soups : INDEX ● Lentil Soups : INDEX ● Peanut Soups : INDEX ● Potato Soups : INDEX ● Avgolemo : COLLECTION ● Baked Potato Soup ● Bean Soups : COLLECTION ● Beef Barley Soup ● 2 Beer Cheese Soups : COLLECTION ● Borscht : COLLECTION ● Buendner Gerstensuppe (Barley soup) ● Busecca Ticinese (Tripe soup with garlic bread) ● Cabbage Soup ("Of Cabbages and Cod") ● Callaloo soup ● Chicken Soups : COLLECTION ● Cockaleekie Soup ● Curried Corn and Shrimp Soup ● Curried Pumpkin-Apple Soup ● Diverse Soups : COLLECTION ● Double Coriander-Ginger Cream Soup ● Egg Drop Soup ● Farmworkers' Chile Soup, Rosebud Texas 1906 ● French Onion Soup (1) ● French Onion Soup (2) ● Green Soup ● Jalapeno Cheese Soup ● Leek, Potato, and Spinach Soup http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/soup/index.html (1 of 2) [12/17/1999 12:01:27 PM] Soup ● Lemongrass Soup ● Miso Soup (1) ● Mom's Vegetable Soup ● Mullagatawny Soup (1) ● Mullagatawny Soup (2) ● Noodle Soup(Ash-e Reshteh) ● Pepper Soups : COLLECTION ● Posole : COLLECTION ● Pumpkin Soup ● Pumpkin Soup - COLLECTION ● Quebec Pea Soup / Salted herbs ● Quick & Dirty Miso Soup ● Reuben Soup ● Smoked Red Bell Pepper Soup ● Soups With Cheese : COLLECTION ● Split Pea Soup ● Squash and Orange Soup ● Sweet & Sour Cabbage Soup ● Posole : COLLECTION ● Tomato Soups / Gazpacho : COLLECTION ● Tortellini Soups : COLLECTION ● Two Soups (Stephanie da Silva) ● Vegetable Soup ● Vegetarian Posole ● Vermont Cheddar Cheese Soup ● Watercress Soup amyl http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/soup/index.html -

Soups & Stews Cookbook

SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK *RECIPE LIST ONLY* ©Food Fare https://deborahotoole.com/FoodFare/ Please Note: This free document includes only a listing of all recipes contained in the Soups & Stews Cookbook. SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare COMPLETE RECIPE INDEX Aash Rechte (Iranian Winter Noodle Soup) Adas Bsbaanegh (Lebanese Lentil & Spinach Soup) Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Almond Soup Artichoke & Mussel Bisque Artichoke Soup Artsoppa (Swedish Yellow Pea Soup) Avgolemono (Greek Egg-Lemon Soup) Bapalo (Omani Fish Soup) Bean & Bacon Soup Bizar a'Shuwa (Omani Spice Mix for Shurba) Blabarssoppa (Swedish Blueberry Soup) Broccoli & Mushroom Chowder Butternut-Squash Soup Cawl (Welsh Soup) Cawl Bara Lawr (Welsh Laver Soup) Cawl Mamgu (Welsh Leek Soup) Chicken & Vegetable Pasta Soup Chicken Broth Chicken Soup Chicken Soup with Kreplach (Jewish Chicken Soup with Dumplings) Chorba bil Matisha (Algerian Tomato Soup) Chrzan (Polish Beef & Horseradish Soup) Clam Chowder with Toasted Oyster Crackers Coffee Soup (Basque Sopa Kafea) Corn Chowder Cream of Celery Soup Cream of Fiddlehead Soup (Canada) Cream of Tomato Soup Creamy Asparagus Soup Creamy Cauliflower Soup Czerwony Barszcz (Polish Beet Soup; Borsch) Dashi (Japanese Kelp Stock) Dumpling Mushroom Soup Fah-Fah (Soupe Djiboutienne) Fasolada (Greek Bean Soup) Fisk och Paprikasoppa (Swedish Fish & Bell Pepper Soup) Frijoles en Charra (Mexican Bean Soup) Garlic-Potato Soup (Vegetarian) Garlic Soup Gazpacho (Spanish Cold Tomato & Vegetable Soup) 2 SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food -

History, Benefits, Food List & Recipes

History, Benefits, Food List & Recipes The Daniel fast brings healing breakthrough in the body, mind and spirit. “This is the fast that I have chosen…to loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, to let the oppressed go free, and that you break every yoke. Then your light shall break forth like the morning, Your healing shall spring forth.” – Isaiah 58:6 HISTORY What is a fast? Fasting is abstaining from something like food, drink or entertainment for a period of time. There are many types of fasts which include: -Standard Fast (water only) -Absolute Fast (No water or food) -Partial Fast (restrict certain food and drink categories) -Intermittent Fast (Only eat during small daily window, for example: 1pm-6pm) What is the Daniel Fast? The Daniel Fast is a biblically based partial fast referenced in the Bible, particularly in two sections of the Book of Daniel: “Please test your servants for ten days, and let them give us vegetables [pulses] to eat and water to drink.” Daniel 1:12 “In those days I, Daniel, was mourning three full weeks. I ate no pleasant food, no meat or wine came into my mouth, nor did I anoint myself at all, till three whole weeks were fulfilled.” Daniel 10: 1-2 The Daniel Fast Story Daniel was among the best and the brightest of the Israelites of his time. In the book of Daniel in the Bible, the backdrop is set: King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon had seized Jerusalem, the capital city of Judah, and had taken King Jehoiakam captive and overrun God’s temple. -

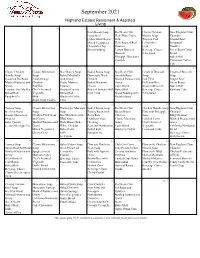

Month at a Glance

September 2021 Highland Estates Retirement & Assisted Living 29 30 31 Sep 1 2 3 4 Bean Bacon Soup Red Bean Chili Classic Chicken New England Clam Fajita Beef Herb Wine Gravy Noodle Soup Chowder Cuban Black Beans Pork Tropical Cod Ground Beef Mixed Vegetables Herb Roasted Red Lemon Rice Stroganoff Chocolate Chip Potatoes Corn Noodles Bread Pudding Lemon Buttered Beverage Choice Green Bean Carrot Broccoli Jello Salad Blend Pineapple Blueberry Baked Roll Crumble Cinnamon Coffee Cake 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Classic Chicken Classic Minestrone Beef Barley Soup Baked Potato Soup Red Bean Chili Cream of Broccoli Cream of Broccoli Noodle Soup Soup Baked Meatballs Homestyle Fried Swedish Patty Soup Soup Seasoned Pot Roast Asian Orange with Gravy Chicken Mashed Potatoes and Cod Fillet Ginger Beef Mashed Potatoes and Chicken Garlic Mashed Baked Macaroni Gravy Delicious Rice Green Beans Gravy Pad Thai Potatoes Cheese Capri Blend Steamed Broccoli Baked Roll Country Trio Medley Chef's Steamed Roasted Carrots Roasted Tomato Half Baked Roll Beverage Choice Rainbow Cake Baked Roll Vegetable Baked Roll Fruit Crisp Bread Pudding with 7-Up Salad Pumpkin Pie Milk Blueberry Coffee Vanilla Sauce Sugar Drop Cookie Cake 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Tomato Soup Classic Minestrone Hamburger Macaroni Baked Potato Soup Red Bean Chili Chicken Noodle Soup New England Clam Beef Pot Roast Soup Soup Turkey Roast with Bacon Ranch Ham with Pineapple Chowder Roasted Rosemary Chicken Fried Steak Beef Rib Bites with Zesty Rub Chicken Sauce BBQ Meatloaf Potatoes and Gravy BBQ Sauce Cranberry -

DAILY SPECIALS SEPTEMBER 2016 Mother Mcauley High School

DAILY SPECIALS SEPTEMBER 2016 Mother McAuley High School LUNCH MENU MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 12 Chicken Noodle Soup Chef's Choice Soup Lunch Price: $4.00-$5.50 Milk: $.75 Vegetable Quiche with Chicken Tenders with Curley soup, salad or fries Fries and soup or salad Daily Offerings: Italian Sausage Sandwich with Pepper Jack BBQ Burger Homemade Soup peppers and onions and choice with Curley Fries Pizza of side Grilled or Breaded Chicken 56789 Sandwich Cream of Chicken Soup Pasta Fagioli Soup Cream of Broccoli Soup Chef's Choice Soup Hamburger LABOR DAY Cheeseburger General Tso Chicken with Baked Parmesan Tilapia with Meatball Sub Sandwich Teriyaki Chicken with Hot Dog NO CLASSES fried rice & fortune cookie Rice Pilaf and fresh vegetable with choice of side Cilantro Lime Rice Made-to-Order Salad Made-to-Order Deli/Panini Steak Fajita BBQ Ribette Sandwich Avocado, Tomato & Chicken Cheese Ravioli with garlic bread Sandwich with choice of side Sandwich with choice of side All items may be purchased a la carte or be combined 12 13 14 15 16 into a lunch meal. Chicken Noodle Soup Cream of Chicken Soup Bean with Bacon Soup Chicken Tortellini Soup Chef's Choice Soup Chicken Caesar Wrap with Homemade Meatloaf with Mashed Sandy's Italian Beef Sandwich Sloppy Joe Sandwich with Italian Rotini Casserole with choice of side Potatoes and fresh vegetable with fries, soup or salad tater tots, soup or salad garlic bread Taco Salad Bowl Turkey Bacon Wrap with Rodeo Wrap with Gordonada Burrito fries, soup or salad fries, soup or salad Individual Cheese Pizza 19 20 21 22 23 Vegetable Soup Cream of Chicken Soup French Onion Soup Cream of Broccoli Soup Chef's Choice Soup Breakfast for Lunch Cheese Tortellini with Marinara BBQ Chicken with oven browned Maxwell St. -

2000 Annual Recipe Index

Annual Recipe Index Y our guide to every recipe title in our year-2000 issues ® APPETIZERS Dried Plum-and-Port Bread, Nov 140 Lemon-Honey Drop Cookies, Dec 140 English Muffins, Sept 111 Mocha Double-Fudge Brownies, June 202 Antipasto Bowl, Dec 100 Festive Fruit Soda Bread, Nov 142 Molasses Crackle Cookies, May 210 Artichokes With Roasted-Pepper Dip, Dec 178 Fig-Swirl Coffeecake, Nov 186 Oatmeal Cookies With A-Peel, June 192 Asian-Spiced Pecans, Nov 179 Flaxseed Bread, J/F 168 Ooey-Gooey Peanut Butter-Chocolate Brownies, Cajun Tortilla Chips, J/F 159 Fresh Cranberry Muffins, Dec 128 Sept 156 Celestial Chicken, Mint, and Cucumber Skewers Fresh Fig Focaccia, Aug 152 Peanut Butter-Chocolate Chip Brownies, June 198 With Spring Onion Sauce, July 106 Fruit-and-Nut Bread, J/F 103 Peanut Butter-Crispy Rice Bars, Sept 156 Cosmic Crab Salad With Corn Chips, July 106 Herbed Focaccia, Mar 138 Power Biscotti, Nov 198 Country Chicken Pâté, July 140 Honey Twists, June 197 Raspberry-Cream Cheese Brownies, June 200 Creamy Feta-Spinach Dip, J/F 158 Jalapeño Corn Bread, Nov 122 Raspberry Strippers, Dec 134 Cumin-Spiked Popcorn, July 96 Jamaican Banana Bread, Apr 212 Sesame-Orange Biscotti, Nov 214 Forest-Mushroom Dip, J/F 156 Kim’s Best Pumpkin Bread, Oct 157 Snickerdoodle Biscotti, Nov 202 Hot Bean-and-Cheese Dip, J/F 155 Lavender-Apricot Swirls, June 180 Spicy Oatmeal Crisps, Dec 130 Indian Egg-Roll Strips, J/F 159 Lavender-Honey Loaf, June 182 Toffee Biscotti, Nov 200 Italian Baguette Chips, J/F 156 Lemon-Glazed Zucchini Quick Bread, June 176 Truffle-Iced -

Continuing Survey of Food Intakes, by Individuals

PB89-205538 PART 1 OF 2 United States Department of C S F11 Documentation Agriculture Human Nutrition Information Service Nationwide Food Consumption Survey Nutrition Continuing Survey of Food Intakes Monitoring Division by Individuals NFCS. CSFII Report No. 86-4 Documentation Low-income Women 19 -50 Years and Their Children 1-5 Years, 4 Days 1986 Distributed by: National Technical Information Service REPRODUCED BY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE SPRINGFIELD, VA 22161 Chapter 1 Introduction DATASETa (SFII86-4 CCNTdI M SURVEY OF POCD INTh1 BY IMIVMMS Low-Inds Women 19-50 Years of Age and Their Children 1.5 Years of Age 4 Days. 1986 Tape Contents Fili No. Intruba ram ,p^.p. .............................................. 1 le"Design Data Collection Sample Weights Data messing Nutrient Data Base Data Cleaning Documentatim for Derivation of Calculated Variables Calculated by Rmm Nutritim Information Service 1.BousehoId income as a percent of poverty level 2.Usual amount of money spent per week food broug3.t into the home (by wave) 3.Usual amount of money spent per cae& on food bcazght and eaten away from home (by wave) 4.Body mass index for participating w 5.Is individual the meal planner/ preparer7 6. Race of childnv 7.t ational origin children 8.Fhiployment status of male head of lkmsehold 9.5mloyn ent status of fenale respondent l0, tritive values, n-day average 3-1 Mich waves were cmpleted? 12.Nimber of waves competed 13.Household ninthly income 14.Imputed yearly household income Recommended Dietary Allowances, 1480 References Glossary Dataset Characteristics and Fomnet ......................... 2 File Characteristics File Structure Special Notes Dataset four t Control Courts for Selected Variables ..................... -

Churston Traditional Where You'll Find the West Country's Finest Food And

Churston Tradiional Where you’ll find te West Country’s finest food and drink… RECIPES JANUARY 2017 January: the month when so many people need to tighten their belts, though find that thanks to Christmas this is no longer possible. The month when some people still make resolutions, the state urges us to give up booze, and the cupboards in the kitchen continue to give up those delicacies which we absolutely had to have for Christmas but forgot about as soon as the turkey was cold. But if you want to save money and lose weight while still keeping warm there is only one word for it: soup. Soup-making at home is rapidly coming back into fashion as more and more people discover that there’s more to soup that what coms in a tin or a packet and that tasty, satisfying soups aren’t anything like as expensive as some of the newly-emerged specialist soup companies would have us believe. And also that the best soups are those which, generally speaking, only have a minimal meat content. We’ve got some ideas for you this month including a classic minestrone, a soup which has been degraded and based probably more than any other by the food industry. The name’s derived from minestra, one of the general Italian terms for soup (the other being zuppa) and its great advantage of minestrone is that it can be put together with almost any combination of ingredients as long as a few key ones are included. There are local variations in Italy, of course, in the same way as we have regional variations for our food. -

SAMPLE for HANDOUT Ris' Soup Kitchen Menu

Please visit risdc.com or our Facebook page Friday for our daily menus! March 27 Soup Kitchen Monday - Friday: 12pm-7pm; Saturday & Sunday: CLOSED Free delivery available to our West End and adjacent neighborhoods from 2-4pm *Please order by 1 pm for lunch pick up or afternoon delivery* *Please order by 4 pm for dinner pick up* Today's Care Package $15 CLASSIC CREAM OF TOMATO SOUP chives, asiago cheese, olive oil OR CHICKEN LIME TORTILLA SOUP sour cream, cilantro, tortilla strips ROMAINE WEDGE cherry tomatoes, Maytag blue and bacon, creamy blue cheese and white balsamic vinaigrette POPPY SOURDOUGH LOAF Daily Offerings CRISPY THAI BRUSSELS SPROUTS 10 bacon, peanuts, chili sauce CHICKEN MILANESE 22 lemon-asiago crust, capicola and spinach salad, roasted potatoes tomato caper vinaigrette, garlic aioli CROWN OF CAULIFLOWER 20 spaghetti squash, lentils, yogurt, pine nuts, mint and pomegranate LIME MIROIR 10 lime bavarian cheesecake with raspberry sauce Weekend Wine Basket $50 GREEK SALAD feta, mozzarella, cucumbers, tomatoes, artichokes, kalamata olives, fennel, cured lemon, herb vinaigrette CHEESE WEDGE Petit Basque, leek-onion marmalade, fennel crisps LOAF OF DAILY BREAD Choose a bottle of wine from John's wine list below! See below for more! Take Me Home Wine and Cocktails to Go! CHICKEN POT PIE FOR ONE TODAY'S SELECTIONS FROM JOHN'S LIST (FROZEN) 15 AT 50% OFF LIST PRICE Chardonnay, Domaine Gueguen $30 SOUPS 16/QT Pinot Grigio, Branizzi $18 potato, leek and bacon soup *limited quantities Gruner Veltliner, Gobelsberg $26 white bean and kale soup Albarino, Doelas $28 beef and cabbage borscht (frozen) Rose, Whole Buffalo $24 classic cream of tomato soup Sparkling, Veuve Ambal 'Blanc de Blanca' $24 bourbon butternut squash soup Malbec, Areo $20 chicken lime tortilla soup Rioja, Cune Crianza $22 SALADS Cotes du Rhone Villages, Framille Perrin $24 greek salad, $12/pint Pinot Noir, Siduri $34 kale and brussels sprout salad, $10 Cabernet Sauvignon, Enos $34 *limited quantities TODAY'S SELECTION FROM HAND SWIRLED ICE CREAM RAVI'S COCKTAIL LAB.. -

Czech Cuisine Contents

Czech Cuisine Contents GOING BACK IN TIME 2 I. Hors d’Oeuvres 7 II. Soups 8 III. Main Courses 10 MEAT DISHES 10 Beef 10 Mutton/Lamb 12 Pork 13 Poultry 15 Fish 16 Game 17 MEATLESS DISHES 18 IV. Sweet Dishes and Desserts 21 V. Side Dishes 24 VI. Small Dishes 26 VII. Cheese 27 VIII. Beverages 28 IX. Some Useful Advice 35 Come and taste! www.czechtourism.com Introduction Travelling is by far the best way to acquaint oneself with different countries. Needless to say getting to know the basic features of the culture and traditions of the visited country also involves tasting the specialities of its national cuisine. Sometimes this may require some courage on the visitor's part, sometimes it may provide agreeable palate sensations to be remembered for years. In our opinion, a piece of expert advice may always come in handy. And this is the aim of the publication you have in your hands. Going Back in Time Nature has been generous to the original inhabitants of the Czech Republic giving them a wealth of gifts to live on, including an abundance of fish in the rivers and game in the forests, as well as fertile fields. Besides that, poultry, cattle and sheep breeding throve in the Czech lands. Popular meals included soups, various kinds of gruel and dishes prepared from pulses. The Czech diet was varied and substantial, and before long it was supplemented by beer and wine since vine-grapes have from time immemorial been cultivated successfully in the warm climate of the Moravian and Bohemian lowlands. -

List of Recipes

NOW YOU'RE COOKING! 19 Mar 2020 11:20 am Food-for-Thought Software www.ffts.com RECIPE CATEGORIES: Cookbook: d:\constant\projects & hobbies\recipes\nyc recipes\rhonda's cookbook.gcf Appetizers (52 recipes) Almost-Famous Corn Salsa Apple Chutney Bacon Marmalade Pecan Bites Baked Brie With Caramelized Onions Bits and Bites Blue Cheese And Shallot Dip Brie En Crute Bruschetta Rustica Buffalo Mozzarella Caramel Corn Cheddar Poppy Moon Crackers Cheesy Garlic Fingers Cheesy Garlic Fingers - SS Chicken Dip Chicken Wings Chili Con Queso Classic Spinach Dip Cornbread Muffins Curried Chicken Salad in Lettuce Cups Deviled Eggs Deviled Eggs With Curry Deviled Salmon Cakes Duck Rillettes (or Rabbit) Easy Corn Fritters Garllic Bread Grilled Salmon or Trout Guacamole Honey Garlic Chicken Wings Honey Mustard Dipping Sauce Hot Corn Dip Hummus - Festive Hummus - Moosewood Hummus - Suzanne Somers Mango-Curry Shrimp Salad in Wonton Cups Marinated Feta Cheese Mexican Dip Mushroom Tart Pear, Leek And Gruyere Turnovers Pico de Gallo Pigs in a Blanket Pigs in a Blanket (Hot Dog) - Baking Powder Puffs Salsa - Roasted Tomato Salsa Verde Samosas Shortbread - Cheddar & Rosemary Spanakopita Spiced Pecans Spiced Ritz Minis Page 2 Stuffed Mushrooms Summer Vegetable Rolls Warm Crab Dip Breads (16 recipes) Baguettes Biscuits - Cream Drop Bread - No Knead Chinese Pancakes Cornbread Muffins Dark Rye Bread French Bread Honey Oatmeal Bread Light Rye Bread (Swedish Limpa) Pita Shredded Wheat Bread Stollen Wheat Bran Bread White Bread Whole Wheat Bread Get 1 1/2 Lb Recipe From -

HIA HABITAT SOUP COOK-OFF February 17, 2018

HIA HABITAT SOUP COOK-OFF February 17, 2018 1 Another wonderful Habitat Interfaith Alliance Soup Cook- Off, with dozens of delicious treats provided by cooks from B’nai Havurah, Central Christian Church, Christ the King Catholic Church, First Universalist Church, Hebrew Educational Alliance, Prairie Unitarian Universalist Church, Rodef Shalom, St. Andrew United Methodist Church, St. Thomas Episcopal Church, Temple Emanuel, Temple Micah, Temple Sinai and Trinity United Methodist Church. This cookbook includes as many recipes as we could gather at the event: unfortunately, not all included the cook’s name, but you know who you are! Next year, we will have a plan in place to ensure proper credit. Some also feature ingredients but no directions: but with soup, it’s hard to go wrong. Here are the winners (winning recipes also noted throughout the cookbook): KOSHER FANCIFULLY FABULOUS: Chicken Matzoh Ball Soup, Vivian Chandler, HEA MEAT HAPPILY HEARTY: Southwest Chicken Barley Chili, Patti Parson, Temple Micah CAPTIVATING CUISINE: Basque Soup, Judy Peterson, First Universalist Church INGENIOUS INSPIRATION: Matzoh Pho, Carole Smith, B’nai Havurah VEGETARIAN HAPPILY HEARTY: Vegetarian Chili – no cook listed CAPTIVATING CUISINE: Thai Pumpkin Soup, Barbara Zeidman, Temple Sinai. INGENIOUS INSPIRATION: Sweet Potato Chili, Sarah Rovner, Temple Micah THE PEOPLE'S CHOICE WINNER: Debra Krebs, Trinity United Methodist Church 2 NON-VEGETARIAN SOUPS 3 Basque Soup CAPTIVATING CUISINE, Meat 1 lb Italian sausage 1 T lemon juice 1/2 c onions, chopped 1 c cabbage,