3. Alienable Vs. Inalienable Possessive Constructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

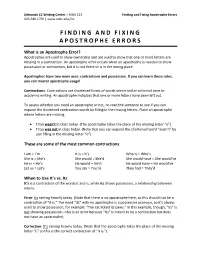

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

The “Person” Category in the Zamuco Languages. a Diachronic Perspective

On rare typological features of the Zamucoan languages, in the framework of the Chaco linguistic area Pier Marco Bertinetto Luca Ciucci Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa The Zamucoan family Ayoreo ca. 4500 speakers Old Zamuco (a.k.a. Ancient Zamuco) spoken in the XVIII century, extinct Chamacoco (Ɨbɨtoso, Tomarâho) ca. 1800 speakers The Zamucoan family The first stable contact with Zamucoan populations took place in the early 18th century in the reduction of San Ignacio de Samuco. The Jesuit Ignace Chomé wrote a grammar of Old Zamuco (Arte de la lengua zamuca). The Chamacoco established friendly relationships by the end of the 19th century. The Ayoreos surrended rather late (towards the middle of the last century); there are still a few nomadic small bands in Northern Paraguay. The Zamucoan family Main typological features -Fusional structure -Word order features: - SVO - Genitive+Noun - Noun + Adjective Zamucoan typologically rare features Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition All Zamucoan languages present a morphological tripartition in their nominals. The base-form (BF) is typically used for predication. The singular-BF is (Ayoreo & Old Zamuco) or used to be (Cham.) the basis for any morphological operation. The full-form (FF) occurs in argumental position. -

Inalienable Possession in Swedish and Danish – a Diachronic Perspective 27

FOLIA SCANDINAVICA VOL. 23 POZNAŃ 20 17 DOI: 10.1515/fsp - 2017 - 000 5 INALIENABLE POSSESSI ON IN SWEDISH AND DANISH – A DIACHRONIC PERSP ECTIVE 1 A LICJA P IOTROWSKA D OMINIKA S KRZYPEK Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań A BSTRACT . In this paper we discuss the alienability splits in two Mainland Scandinavian language s, Swedish and Danish, in a diachronic context. Although it is not universally acknowledged that such splits exist in modern Scandinavian languages, many nouns typically included in inalienable structures such as kinship terms, body part nouns and nouns de scribing culturally important items show different behaviour from those considered alienable. The differences involve the use of (reflexive) possessive pronouns vs. the definite article, which differentiates the Scandinavian languages from e.g. English. As the definite article is a relatively new arrival in the Scandinavian languages, we look at when the modern pattern could have evolved by a close examination of possessive structures with potential inalienables in Old Swedish and Old Danish. Our results re veal that to begin with, inalienables are usually bare nouns and come to be marked with the definite article in the course of its grammaticalization. 1. INTRODUCTION One of the striking differences between the North Germanic languages Swedish and Danish on the one hand and English on the other is the possibility to use definite forms of nouns without a realized possessive in inalienable possession constructions. Consider the following examples: 1 The work on this paper was funded by the grant Diachrony of article systems in Scandi - navian languages , UMO - 2015/19/B/HS2/00143, from the National Science Centre, Poland. -

'Appositive Possession in Ainu and Around the Pacific'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Appositive possession in Ainu and around the Pacific Bugaeva, Anna ; Nichols, Johanna ; Bickel, Balthasar Abstract: Some languages around the Pacific have multiple possessive classes of alienable constructions using appositive nouns or classifiers. This pattern differs from the most common kind of alienable/i- nalienable distinction, which involves marking, usually affixal, on the possessum, and has only one class of alienables. The Japanese language isolate Ainu has possessive marking that is reminiscent of the Circum-Pacific pattern. It is distinctive, however, in that the possessor is coded not as a dependent in an NP but as an argument in a finite clause, and the appositive word is a verb. This paper givesa first comprehensive, typologically grounded description of Ainu possession and reconstructs the pattern that must have been standard when Ainu was still the daily language of a large speech community; Ainu then had multiple alienable class constructions. We report a cross-linguistic survey expanding pre- vious coverage of the appositive type and show how Ainu fits in. We split alienable/inalienable into two different phenomena: argument structure (with types based on possessibility: optionally possessible, obligatorily possessed, and non-possessible) and valence (alienable, inalienable classes). Valence-changing operations are derived alienability and derived inalienability. Our survey classifies the possessive systems of languages in these terms. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2021-2079 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-204338 Journal Article Published Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

Assibilation Or Analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean Noun Stem-Endings*

Assibilation or analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean noun stem-endings* Ponghyung Lee (Daejeon University) This paper discusses two approaches to the nominal stem-endings in Korean inflection including loanwords: one is the assibilation approach, represented by H. Kim (2001) and the other is the analogy approach, represented by Albright (2002 et sequel) and Y. Kang (2003b). I contend that the assibilation approach is deficient in handling its underapplication to the non-nominal categories such as verb. More specifically, the assibilation approach is unable to clearly explain why spirantization (s-assibilation) applies neither to derivative nouns nor to non-nominal items in its entirety. By contrast, the analogy approach is able to overcome difficulties involved with the assibilation position. What is crucial to the analogy approach is that the nominal bases end with t rather than s. Evidence of t-ending bases is garnered from the base selection criteria, disparities between t-ending and s-ending inputs in loanwords. Unconventionally, I dare to contend that normative rules via orthography intervene as part of paradigm extension, alongside semantic conditioning and token/type frequency. Keywords: inflection, assibilation, analogy, base, affrication, spirantization, paradigm extension, orthography, token/type frequency 1. Introduction When it comes to Korean nominal inflection, two observations have captivated our attention. First, multiple-paradigms arise, as explored in previous literature (K. Ko 1989, Kenstowicz 1996, Y. Kang 2003b, Albright 2008 and many others).1 (1) Multiple-paradigms of /pʰatʰ/ ‘red bean’ unmarked nom2 acc dat/loc a. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰatʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e b. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰaʧʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e c.