Master Chronotopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George B. Seitz Motion Picture Stills, 1919-Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8h41trq No online items Finding Aid for the George B. Seitz motion picture stills, 1919-ca. 1944 Processed by Arts Special Collections Staff, pre-1999; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie Graham and Caroline Cubé; supplemental EAD encoding by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George B. PASC 31 1 Seitz motion picture stills, 1919-ca. 1944 Title: George B. Seitz motion picture stills Collection number: PASC 31 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 3.8 linear ft.(9 boxes) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1939 Date (inclusive): ca. 1920-ca. 1942, ca. 1930s Abstract: George B. Seitz was an actor, screenwriter, and director. The collection consists of black and white motion picture stills representing 30-plus productions related to Seitz's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Seitz, George B., 1888-1944 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

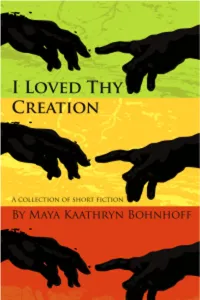

I Loved Thy Creation

I Loved Thy Creation A collection of short fiction by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Bahá’u’lláh Copyright 2008, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff and Juxta Publishing Limited. www.juxta.com. Cover image "© Horvath Zoltan | Dreamstime.com" ISBN 978-988-97451-8-9 This book has been produced with the consent of the original authors or rights holders. Authors or rights holders retain full rights to their works. Requests to reproduce the contents of this work can be directed to the individual authors or rights holders directly or to Juxta Publishing Limited. Reproduction of this book in its current form is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license outlined below. This book is released as part of Juxta Publishing's Books for the World program which aims to provide the widest possible access to quality Bahá'í-inspired literature to readers around the world. Use of this book is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license: 1. This book is available in printed and electronic forms. 2. This book may be freely redistributed in electronic form so long as the following conditions are met: a. The contents of the file are not altered b. This copyright notice remains intact c. No charges are made or monies collected for redistribution 3 The electronic version may be printed or the printed version may be photocopied, and the resulting copies used in non-bound format for non-commercial use for the following purposes: a. Personal use b. Academic or educational use When reproduced in this way in printed form for academic or educational use, charges may be made to recover actual reproduction and distribution costs but no additional monies may be collected. -

DT Filmography

Dolly Tree Filmography Legend The date after the title is the release date and the number following is the production number Main actresses and actors are listed, producer (P) and director (D) are given, along with dates for when the film was in production, if known. All credits sourced from AFI, IMDB and screen credit, except where listed Included are contentious or unclear credits (listed as Possible credits with a ? along with notes or sources) FOX FILMS 1930-1932 1930 Just Imagine (23/11/30) Maureen O’Sullivan, Marjorie White David Butler (D) Possible Credits 1930 ? Soup to Nuts ? Part Time Wife 1931 Are You There? (3/5/31) Hamilton MacFadden (D) Annabelle’s Affairs (14/6/31) Jeanette Macdonald Alfred Werker (D) Goldie (28/6/31) Jean Harlow Benjamin Stoloff (D) In production mid April – mid May 1931 Bad Girl (12/9/31) Sally Eilers, Minna Gombell Frank Borzage (D) In production July 1931 Hush Money (5/7/31) Joan Bennett, Myrna Loy Sidney Lanfield (D) In production mid April – mid May 1931 The Black Camel (June 1931) Sally Eilers, Dorothy Revier Hamilton MacFadden (D) In production mid April – early May 1931 Transatlantic (30/8/31) Myrna Loy, Greta Nissen William K. Howard (D) In production mid April – early May 1931 Page 1 The Spider (27/9/31) Lois Moran William C. Menzies (D) In production mid June – early July 1931 Wicked (4/10/31) Una Merkel, Elissa Landi Allan Dwan (D) In production mid June – early July 1931 Skyline (11/10/31) Myrna Loy, Maureen O’Sullivan Sam Taylor (D) In production June 1931 The Brat (20/9/31) Sally O’Neill, -

Web Paramount Historical Calendar 6-12-2016.Xlsx

Paramount Historical Calendar Last Update 612-2016 Paramount Historical Calendar 1928 - Present Performance Genre Event Title Performance Performan Start Date ce End Date Instrumental - Group Selections from Faust 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie Memories 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie News of the Day 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Instrumental - Group Organs We Have Played 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Musical Play A Merry Widow Revue 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Musical Play A Merry Widow Revue 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Musical Play A Merry Widow Revue 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Dance Accent & Jenesko 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Dance Felicia Sorel Girls 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Vocal - Group The Royal Quartette 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Comedian Over the Laughter Hurdles 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Vocal - Group The Merry Widow Ensemble 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie Feel My Pulse 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Instrumental - Individual Don & Ron at the grand organ 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie The Big City 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Instrumental - Individual Don & Ron at the grand organ 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Variety Highlights 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Comedian A Comedy Highlight 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Vocal - Individual An Operatic Highllight 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Variety Novelty (The Living Marionette) 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Dance Syncopated 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Dance Slow Motion 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Dance Millitary Gun Drill 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Comedian Traffic 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Instrumental - Group novelty arrangement 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Comedian Highlights 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Movie West Point 3/15/1928 3/21/1928 Instrumental - Individual Don & Ron at the grand organ 3/15/1928 3/21/1928 Variety -

Meanderings in New Jersey's Medical History

Meanderings in New Jersey’s Medical History Meanderings in New Jersey’s Medical History Michael Nevins iUniverse, Inc. Bloomington Meanderings in New Jersey’s Medical History Copyright © 2011 by Michael Nevins. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. iUniverse books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting: iUniverse 1663 Liberty Drive Bloomington, IN 47403 www.iuniverse.com 1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677) Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them. Any people depicted in stock imagery provided by Thinkstock are models, and such images are being used for illustrative purposes only. Certain stock imagery © Thinkstock. ISBN: 978-1-4620-5467-1 (sc) ISBN: 978-1-4620-5468-8 (ebk) Printed in the United States of America iUniverse rev. date: 09/23/2011 CONTENTS Introduction Just for the Fun of It vii 1. “A Very Healthful Air” 1 2. Hackensack’s First Hospital: October—November,1776 5 3. You’ve Got Mail 25 4. The Stormy Petrel of American Medical Education 30 5. -

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Architectural Set Plans PASC.0024

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8639s1s No online items Finding Aid for the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Architectural Set Plans PASC.0024 Finding aid prepared by Arts Special Collections staff, pre-1999; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie L. Graham and Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 August 16. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections PASC.0024 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer architectural set plans Creator: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0024 Physical Description: 148.0 Linear Feet(354 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1917-1950 Abstract: During its peak years Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer (MGM) lineup included many of the most creative artists, technicians, and stars in the film industry. The collection consists of original architectural designs, sketches, and blueprint set plans for MGM motion picture productions. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materias are in English. Restrictions on Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical objects belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. All other rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Medical History of Michigan

Library of Congress Medical history of Michigan MEDICAL HISTORY OF MICHIGAN A “Famous Last Word”(Apologies to Ted CooK) “Histories of medicine by doctors, of lawby lawyers, of art by critics, are from ourpoint of view written by untrained amateurs.” —Dixon Ryan Fox in AmericanHistorical Review, January, 1930. Dr. William Beaumont From The Life and Letters of Dr. William Beaumont by Jesse S. Myer. C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis. MEDICAL HISTORY of MICHIGAN VOLUME I Compiled and Edited by a CommitteeC. B. BURR; M. D., Chairmanand Published under the auspices of theMichigan State Medical SocietyTHE BRUCE PUBLISHING COMPANY Minneapolis and Saint Paul 1930 Copy 2 R249.M551930Copy 2 COPYRIGHT, 1930THE BRUCE PUBLISHING COMPANY# ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDPrinted in the United States of America APR 24 1931#©C1A 36979C R vii PREFACE At the meeting of the State Medical Society in Lansing in 1926 “a resolution was introduced and passed by the House of Delegates to get started some work on the history of medicine in the State of Michigan.” Pursuant to this resolution, under instruction Medical history of Michigan http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.1995a Library of Congress of President-Elect J. B. Jackson, the following notification was issued:Grand Rapids, Michigan,December 7, 1926. Dr. C. B. Burr, Flint, Chairman,Dr. J. H. Dempster, Detroit,Dr. W. H. Sawyer, Hillsdale,Dr. J. D. Brook, Grandville,Dr. W. J. Kay, Lapeer, Please be advised that President Jackson has appointed the above members to form the committee instructed to compile a Medical History of Michigan. If there is any service that this office can render to the Committee, you have but to command it. -

Pre-Code Hollywood 1930-1934

Pre-Code Hollywood FILM AND CULTURE / JOHN BELTON, GENERAL EDITOR Film and Culture / A Columbia University Press series / Edited by John Belton What Made Pistachio Nuts? Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Henry Jenkins Style, National Identity, Japanese Film Darrell William Davis Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Martin Rubin Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema Projections of War: Rhona J. Berenstein Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Thomas Doherty Masculinity in the Jazz Age Gaylyn Studlar Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: and Comedy Hollywood and Beyond William Paul Robin Wood Laughing Hysterically: American The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Screen Comedy of the 1950s Popular Film Music Ed Sikov Jeff Smith Primitive Passions: Visuality, Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Sexuality, Ethnography, and Popular Culture Contemporary Chinese Cinema Michael Anderegg Rey Chow Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930–1934 Magisterial Vision and the Figure Thomas Doherty of Woman Susan M. White Sexual Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Black Women as Cultural Readers Modernity Jacqueline Bobo James Lastra Pre-Code Hollywood Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930–1934 Thomas Doherty COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS / NEW YORK Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 1999 by Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Doherty, Thomas Patrick. Pre-code Hollywood : sex, immorality, and insurrection in American cinema, 1930–1934 / Thomas Doherty. p. cm. — (Film and culture) Filmography: p.