Molecular Codes for Cell Type Specification in Brn3 Retinal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials Supplementary Table S1: MGNC compound library Ingredien Molecule Caco- Mol ID MW AlogP OB (%) BBB DL FASA- HL t Name Name 2 shengdi MOL012254 campesterol 400.8 7.63 37.58 1.34 0.98 0.7 0.21 20.2 shengdi MOL000519 coniferin 314.4 3.16 31.11 0.42 -0.2 0.3 0.27 74.6 beta- shengdi MOL000359 414.8 8.08 36.91 1.32 0.99 0.8 0.23 20.2 sitosterol pachymic shengdi MOL000289 528.9 6.54 33.63 0.1 -0.6 0.8 0 9.27 acid Poricoic acid shengdi MOL000291 484.7 5.64 30.52 -0.08 -0.9 0.8 0 8.67 B Chrysanthem shengdi MOL004492 585 8.24 38.72 0.51 -1 0.6 0.3 17.5 axanthin 20- shengdi MOL011455 Hexadecano 418.6 1.91 32.7 -0.24 -0.4 0.7 0.29 104 ylingenol huanglian MOL001454 berberine 336.4 3.45 36.86 1.24 0.57 0.8 0.19 6.57 huanglian MOL013352 Obacunone 454.6 2.68 43.29 0.01 -0.4 0.8 0.31 -13 huanglian MOL002894 berberrubine 322.4 3.2 35.74 1.07 0.17 0.7 0.24 6.46 huanglian MOL002897 epiberberine 336.4 3.45 43.09 1.17 0.4 0.8 0.19 6.1 huanglian MOL002903 (R)-Canadine 339.4 3.4 55.37 1.04 0.57 0.8 0.2 6.41 huanglian MOL002904 Berlambine 351.4 2.49 36.68 0.97 0.17 0.8 0.28 7.33 Corchorosid huanglian MOL002907 404.6 1.34 105 -0.91 -1.3 0.8 0.29 6.68 e A_qt Magnogrand huanglian MOL000622 266.4 1.18 63.71 0.02 -0.2 0.2 0.3 3.17 iolide huanglian MOL000762 Palmidin A 510.5 4.52 35.36 -0.38 -1.5 0.7 0.39 33.2 huanglian MOL000785 palmatine 352.4 3.65 64.6 1.33 0.37 0.7 0.13 2.25 huanglian MOL000098 quercetin 302.3 1.5 46.43 0.05 -0.8 0.3 0.38 14.4 huanglian MOL001458 coptisine 320.3 3.25 30.67 1.21 0.32 0.9 0.26 9.33 huanglian MOL002668 Worenine -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A. -

WNT16 Is a New Marker of Senescence

Table S1. A. Complete list of 177 genes overexpressed in replicative senescence Value Gene Description UniGene RefSeq 2.440 WNT16 wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 16 (WNT16), transcript variant 2, mRNA. Hs.272375 NM_016087 2.355 MMP10 matrix metallopeptidase 10 (stromelysin 2) (MMP10), mRNA. Hs.2258 NM_002425 2.344 MMP3 matrix metallopeptidase 3 (stromelysin 1, progelatinase) (MMP3), mRNA. Hs.375129 NM_002422 2.300 HIST1H2AC Histone cluster 1, H2ac Hs.484950 2.134 CLDN1 claudin 1 (CLDN1), mRNA. Hs.439060 NM_021101 2.119 TSPAN13 tetraspanin 13 (TSPAN13), mRNA. Hs.364544 NM_014399 2.112 HIST2H2BE histone cluster 2, H2be (HIST2H2BE), mRNA. Hs.2178 NM_003528 2.070 HIST2H2BE histone cluster 2, H2be (HIST2H2BE), mRNA. Hs.2178 NM_003528 2.026 DCBLD2 discoidin, CUB and LCCL domain containing 2 (DCBLD2), mRNA. Hs.203691 NM_080927 2.007 SERPINB2 serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 2 (SERPINB2), mRNA. Hs.594481 NM_002575 2.004 HIST2H2BE histone cluster 2, H2be (HIST2H2BE), mRNA. Hs.2178 NM_003528 1.989 OBFC2A Oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold containing 2A Hs.591610 1.962 HIST2H2BE histone cluster 2, H2be (HIST2H2BE), mRNA. Hs.2178 NM_003528 1.947 PLCB4 phospholipase C, beta 4 (PLCB4), transcript variant 2, mRNA. Hs.472101 NM_182797 1.934 PLCB4 phospholipase C, beta 4 (PLCB4), transcript variant 1, mRNA. Hs.472101 NM_000933 1.933 KRTAP1-5 keratin associated protein 1-5 (KRTAP1-5), mRNA. Hs.534499 NM_031957 1.894 HIST2H2BE histone cluster 2, H2be (HIST2H2BE), mRNA. Hs.2178 NM_003528 1.884 CYTL1 cytokine-like 1 (CYTL1), mRNA. Hs.13872 NM_018659 tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10d, decoy with truncated death domain (TNFRSF10D), 1.848 TNFRSF10D Hs.213467 NM_003840 mRNA. -

A Genome-Wide Association Study of Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy in African Americans

Journal of Personalized Medicine Article A Genome-Wide Association Study of Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy in African Americans Huichun Xu 1,* ID , Gerald W. Dorn II 2, Amol Shetty 3, Ankita Parihar 1, Tushar Dave 1, Shawn W. Robinson 4, Stephen S. Gottlieb 4 ID , Mark P. Donahue 5, Gordon F. Tomaselli 6, William E. Kraus 5,7 ID , Braxton D. Mitchell 1,8 and Stephen B. Liggett 9,* 1 Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (T.D.); [email protected] (B.D.M.) 2 Center for Pharmacogenomics, Department of Internal Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA; [email protected] 3 Institute for Genome Sciences, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; [email protected] 4 Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; [email protected] (S.W.R.); [email protected] (S.S.G.) 5 Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27708, USA; [email protected] (M.P.D.); [email protected] (W.E.K.) 6 Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; [email protected] 7 Duke Molecular Physiology Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27701, USA 8 Geriatrics Research and Education Clinical Center, Baltimore Veterans Administration -

Genomic Diagnostics Within a Medically Underserved Population: Efficacy and Implications

© American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Genomic diagnostics within a medically underserved population: efficacy and implications Kevin A. Strauss, MD1, Claudia Gonzaga-Jauregui, PhD2, Karlla W. Brigatti, MS1, Katie B. Williams, MD, PhD1, Alejandra K. King, PhD2, Cristopher Van Hout, PhD2, Donna L. Robinson, CRNP1, Millie Young, RNC1, Kavita Praveen, PhD2, Adam D. Heaps, MS1, Mindy Kuebler, MS1, Aris Baras, MD2, Jeffrey G. Reid, PhD2, John D. Overton, PhD2, Frederick E. Dewey, MD2, Robert N. Jinks, PhD3, Ian Finnegan, BA3, Scott J. Mellis, MD, PhD2, Alan R. Shuldiner, MD2 and Erik G. Puffenberger, PhD1 Purpose: We integrated whole-exome sequencing (WES) and Compared to trio analysis, “family” WES (average seven exomes chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) into a clinical workflow per proband) reduced filtered candidate variants from 22 ± 6to to serve an endogamous, uninsured, agrarian community. 5 ± 3 per proband. Nineteen (51%) alleles were de novo and 17 Methods: Seventy-nine probands (newborn to 49.8 years) who (46%) inherited; the latter added to a population-based diagnostic presented between 1998 and 2015 remained undiagnosed after panel. We found actionable secondary variants in 21 (4.2%) of 502 biochemical and molecular investigations. We generated WES data subjects, all of whom opted to be informed. for probands and family members and vetted variants through Conclusion: CMA and family-based WES streamline and rephenotyping, segregation analyses, and population studies. economize diagnosis of rare genetic disorders, accelerate novel Results: The most common presentation was neurological disease gene discovery, and create new opportunities for community-based (64%). Seven (9%) probands were diagnosed by CMA. -

Genomic Landscape and Genetic Heterogeneity in Gastric Adenocarcinoma Revealed by Whole-Genome Sequencing

ARTICLE Received 1 May 2014 | Accepted 3 Oct 2014 | Published 19 Nov 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6477 Genomic landscape and genetic heterogeneity in gastric adenocarcinoma revealed by whole-genome sequencing Swee Seong Wong1,*, Kyoung-Mee Kim2,*, Jason C. Ting1,*, Kun Yu1,w, Jake Fu3, Shawn Liu4, Razvan Cristescu5, Michael Nebozhyn5, Lara Gong4, Yong Gang Yue1, Jian Wang1, Chen Ronghua5, Andrey Loboda5, James Hardwick5,w, Xiaoqiao Liu5, Hongyue Dai5, Jason Gang Jin3, Xiang S. Ye1, So Young Kang2,InGuDo2, Joon Oh Park6, Tae Sung Sohn7, Christoph Reinhard1, Jeeyun Lee6, Sung Kim7 & Amit Aggarwal1 Gastric cancer (GC) is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths. It is known to be a heterogeneous disease with several molecular and histological subtypes. Here we perform whole-genome sequencing of 49 GCs with diffuse (N ¼ 31) and intestinal (N ¼ 18) histological subtypes and identify three mutational signatures, impacting TpT, CpG and TpCp[A/T] nucleotides. The diffuse-type GCs show significantly lower clonality and smaller numbers of somatic and structural variants compared with intestinal subtype. We further divide the diffuse subtype into one with infrequent genetic changes/low clonality and another with relatively higher clonality and mutations impacting TpT dinucleotide. Notably, we dis- cover frequent and exclusive mutations in Ephrins and SLIT/ROBO signalling pathway genes. Overall, this study delivers new insights into the mutational heterogeneity underlying distinct histologic subtypes of GC that could have important implications for future research in the diagnosis and treatment of GC. 1 Lilly Research Labs, Eli Lilly and Co, Indianapolis, Indiana 46285, USA. 2 Department of Pathology & Translational Genomics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 135-710, South Korea. -

Downloaded Per Proteome Cohort Via the Web- Site Links of Table 1, Also Providing Information on the Deposited Spectral Datasets

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Assessment of a complete and classifed platelet proteome from genome‑wide transcripts of human platelets and megakaryocytes covering platelet functions Jingnan Huang1,2*, Frauke Swieringa1,2,9, Fiorella A. Solari2,9, Isabella Provenzale1, Luigi Grassi3, Ilaria De Simone1, Constance C. F. M. J. Baaten1,4, Rachel Cavill5, Albert Sickmann2,6,7,9, Mattia Frontini3,8,9 & Johan W. M. Heemskerk1,9* Novel platelet and megakaryocyte transcriptome analysis allows prediction of the full or theoretical proteome of a representative human platelet. Here, we integrated the established platelet proteomes from six cohorts of healthy subjects, encompassing 5.2 k proteins, with two novel genome‑wide transcriptomes (57.8 k mRNAs). For 14.8 k protein‑coding transcripts, we assigned the proteins to 21 UniProt‑based classes, based on their preferential intracellular localization and presumed function. This classifed transcriptome‑proteome profle of platelets revealed: (i) Absence of 37.2 k genome‑ wide transcripts. (ii) High quantitative similarity of platelet and megakaryocyte transcriptomes (R = 0.75) for 14.8 k protein‑coding genes, but not for 3.8 k RNA genes or 1.9 k pseudogenes (R = 0.43–0.54), suggesting redistribution of mRNAs upon platelet shedding from megakaryocytes. (iii) Copy numbers of 3.5 k proteins that were restricted in size by the corresponding transcript levels (iv) Near complete coverage of identifed proteins in the relevant transcriptome (log2fpkm > 0.20) except for plasma‑derived secretory proteins, pointing to adhesion and uptake of such proteins. (v) Underrepresentation in the identifed proteome of nuclear‑related, membrane and signaling proteins, as well proteins with low‑level transcripts. -

Identification of IFN-Induced Transmembrane Protein 1 With

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 22 March 2021 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.626883 Identification of IFN-Induced Transmembrane Protein 1 With Prognostic Value in Pancreatic Cancer Using Network Module-Based Analysis Lingyun Wu 1†, Xinli Zhu 1†, Danfang Yan 1, Mengmeng Tang 2, Chiyuan Ma 3*† and Senxiang Yan 1*† 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China, 2 Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China, 3 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China Despite improvements reported in diagnosis and treatments in recent decades, Edited by: pancreatic cancer is still characterized by poor prognosis and low survival rate among Xiangqian Guo, Henan University, China solid tumors. Intensive interests have grown in exploring novel predictive biomarkers, Reviewed by: aiming to enhance the efficiency in early detection and treatment prognosis. In this Jiateng Zhong, study, we identified the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in pancreatic cancer by Xinxiang Medical University, China Liang Chen, analyzing five gene expression profiles and established the functional modules according Wuhan University, China to the functional interaction (FI) network between the DEGs. A significant upregulation Guosen Zhang, of the selected DEG, interferon (IFN)-induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1), was Henan University, China *Correspondence: evaluated in several bioinformatics online tools and verified with immunohistochemistry Senxiang Yan staining from samples of 90 patients with pancreatic cancer. Prognostic data showed [email protected] that high expression of IFITM1 associated with poor survival, and multivariate Cox Chiyuan Ma [email protected] regression analysis showed IFITM1 was one of the independent prognostic factors for overall survival. -

ABLIM3 Sirna (M): Sc-140781

SAN TA C RUZ BI OTEC HNOL OG Y, INC . ABLIM3 siRNA (m): sc-140781 BACKGROUND STORAGE AND RESUSPENSION The C. elegans protein UNC-115 mediates axon guidance by modulating the Store lyophilized siRNA duplex at -20° C with desiccant. Stable for at least growth cone Actin cytoskeleton in response to signals received by growth one year from the date of shipment. Once resuspended, store at -20° C, cone receptors. The mammalian homolog of UNC-115 is the Actin-binding LIM avoid contact with RNAses and repeated freeze thaw cycles. protein family member 1 (ABLIM1, also designated Limatin). The ABLIM1 Resuspend lyophilized siRNA duplex in 330 µl of the RNAse-free water pro tein has an N-terminal domain that contains four double zinc finger motifs, pro vided. Resuspension of the siRNA duplex in 330 µl of RNAse-free water which conform to the LIM motif consensus sequence. ABLIM1 binds to F-Actin makes a 10 µM solution in a 10 µM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM through a dematin-like domain and is expressed in retina, brain and muscle EDTA buffered solution. tissue. There are four known isoforms of ABLIM1. The gene encoding ABLIM1 maps to a region of chromosome 10 associated with frequent loss of hetero- APPLICATIONS zygosity in human tumors, thus identifying ABLIM1 as a candidate tumor suppressor gene. ABLIM2 and ABLIM3 show highest expression in muscle ABLIM3 siRNA (m) is recommended for the inhibition of ABLIM3 expression and neuronal tissues, bind to F-Actin, and are localized on stress fibers. They in mouse cells. -

The Pdx1 Bound Swi/Snf Chromatin Remodeling Complex Regulates Pancreatic Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Mature Islet Β Cell

Page 1 of 125 Diabetes The Pdx1 bound Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex regulates pancreatic progenitor cell proliferation and mature islet β cell function Jason M. Spaeth1,2, Jin-Hua Liu1, Daniel Peters3, Min Guo1, Anna B. Osipovich1, Fardin Mohammadi3, Nilotpal Roy4, Anil Bhushan4, Mark A. Magnuson1, Matthias Hebrok4, Christopher V. E. Wright3, Roland Stein1,5 1 Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 2 Present address: Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 3 Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 4 Diabetes Center, Department of Medicine, UCSF, San Francisco, California 5 Corresponding author: [email protected]; (615)322-7026 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online June 14, 2019 Diabetes Page 2 of 125 Abstract Transcription factors positively and/or negatively impact gene expression by recruiting coregulatory factors, which interact through protein-protein binding. Here we demonstrate that mouse pancreas size and islet β cell function are controlled by the ATP-dependent Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling coregulatory complex that physically associates with Pdx1, a diabetes- linked transcription factor essential to pancreatic morphogenesis and adult islet-cell function and maintenance. Early embryonic deletion of just the Swi/Snf Brg1 ATPase subunit reduced multipotent pancreatic progenitor cell proliferation and resulted in pancreas hypoplasia. In contrast, removal of both Swi/Snf ATPase subunits, Brg1 and Brm, was necessary to compromise adult islet β cell activity, which included whole animal glucose intolerance, hyperglycemia and impaired insulin secretion. Notably, lineage-tracing analysis revealed Swi/Snf-deficient β cells lost the ability to produce the mRNAs for insulin and other key metabolic genes without effecting the expression of many essential islet-enriched transcription factors. -

GATA3 Zinc Finger 2 Mutations Reprogram the Breast Cancer

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03478-4 OPEN GATA3 zinc finger 2 mutations reprogram the breast cancer transcriptional network Motoki Takaku1, Sara A. Grimm2, John D. Roberts1, Kaliopi Chrysovergis1, Brian D. Bennett2, Page Myers3, Lalith Perera 4, Charles J. Tucker5, Charles M. Perou6 & Paul A. Wade 1 GATA3 is frequently mutated in breast cancer; these mutations are widely presumed to be loss-of function despite a dearth of information regarding their effect on disease course or 1234567890():,; their mechanistic impact on the breast cancer transcriptional network. Here, we address molecular and clinical features associated with GATA3 mutations. A novel classification scheme defines distinct clinical features for patients bearing breast tumors with mutations in the second GATA3 zinc-finger (ZnFn2). An engineered ZnFn2 mutant cell line by CRISPR–Cas9 reveals that mutation of one allele of the GATA3 second zinc finger (ZnFn2) leads to loss of binding and decreased expression at a subset of genes, including Proges- terone Receptor. At other loci, associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition, gain of binding correlates with increased gene expression. These results demonstrate that not all GATA3 mutations are equivalent and that ZnFn2 mutations impact breast cancer through gain and loss-of function. 1 Epigenetics and Stem Cell Biology Laboratory, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, Durham, NC 27709, USA. 2 Integrative Bioinformatics, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, Durham, NC 27709, USA. 3 Comparative Medicine Branch, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, 27709 Durham, NC, USA. 4 Laboratory of Genome Integrity and Structural Biology, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, Durham, NC 27709, USA. -

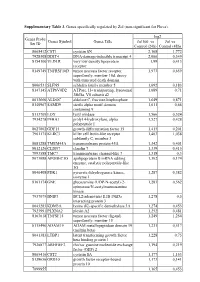

Supplementary Table 3. Genes Specifically Regulated by Zol (Non-Significant for Fluva)

Supplementary Table 3. Genes specifically regulated by Zol (non-significant for Fluva). log2 Genes Probe Genes Symbol Genes Title Zol100 vs Zol vs Set ID Control (24h) Control (48h) 8065412 CST1 cystatin SN 2,168 1,772 7928308 DDIT4 DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4 2,066 0,349 8154100 VLDLR very low density lipoprotein 1,99 0,413 receptor 8149749 TNFRSF10D tumor necrosis factor receptor 1,973 0,659 superfamily, member 10d, decoy with truncated death domain 8006531 SLFN5 schlafen family member 5 1,692 0,183 8147145 ATP6V0D2 ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 1,689 0,71 38kDa, V0 subunit d2 8013660 ALDOC aldolase C, fructose-bisphosphate 1,649 0,871 8140967 SAMD9 sterile alpha motif domain 1,611 0,66 containing 9 8113709 LOX lysyl oxidase 1,566 0,524 7934278 P4HA1 prolyl 4-hydroxylase, alpha 1,527 0,428 polypeptide I 8027002 GDF15 growth differentiation factor 15 1,415 0,201 7961175 KLRC3 killer cell lectin-like receptor 1,403 1,038 subfamily C, member 3 8081288 TMEM45A transmembrane protein 45A 1,342 0,401 8012126 CLDN7 claudin 7 1,339 0,415 7993588 TMC7 transmembrane channel-like 7 1,318 0,3 8073088 APOBEC3G apolipoprotein B mRNA editing 1,302 0,174 enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3G 8046408 PDK1 pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, 1,287 0,382 isozyme 1 8161174 GNE glucosamine (UDP-N-acetyl)-2- 1,283 0,562 epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase 7937079 BNIP3 BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa 1,278 0,5 interacting protein 3 8043283 KDM3A lysine (K)-specific demethylase 3A 1,274 0,453 7923991 PLXNA2 plexin A2 1,252 0,481 8163618 TNFSF15 tumor necrosis