Medicalkaiserperm00smilrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A LOOK BACK at WONDER WOMAN's FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour Sur L'histoire Féministe (Et Un Peu Moins Féministe) De Wonder Woman

Did you know? According to a recent media analysis, films with female stars earnt more at the box office between 2014 and 2017 than films with male heroes. THE INDEPENDENT MICHAEL CAVNA A LOOK BACK AT WONDER WOMAN'S FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour sur l'histoire féministe (et un peu moins féministe) de Wonder Woman uring World War II, as Superman Woman. Marston – whose scientific work their weakness. The obvious remedy is to and Batman arose as mainstream led to the development of the lie-detector test create a feminine character with all the Dpop symbols of strength and morality, the – also outfitted Wonder Woman with the strength of Superman plus all the allure of publisher that became DC Comics needed an empowering golden Lasso of a good and beautiful woman.” antidote to what a Harvard psychologist Truth, whose coils command Upon being hired as an edito- called superhero comic books’ worst crime: veracity from its captive. Ahead rial adviser at All-American/ “bloodcurdling masculinity.” Turns out that of the release of the new Won- Detective Comics, Marston sells psychologist, William Moulton Marston, had der Woman film here is a time- his Wonder Woman character a plan to combat such a crime – in the star- line of her feminist, and less- to the publisher with the agree- spangled form of a female warrior who could, than-feminist, history. ment that his tales will spot- time and again, escape the shackles of a man's light “the growth in the power world of inflated pride and prejudice. 1941: THE CREATION of women.” He teams with not 3. -

Notice of Privacy Practices KAISER PERMANENTE—NORTHWEST REGION Notice of Privacy Practices THIS NOTICE DESCRIBES HOW MEDICAL A

Notice of Privacy Practices KAISER PERMANENTE—NORTHWEST REGION Notice of Privacy Practices THIS NOTICE DESCRIBES HOW MEDICAL AND DENTAL HEALTH INFORMATION ABOUT YOU MAY BE USED AND DISCLOSED AND HOW YOU CAN GET ACCESS TO THIS INFORMATION. PLEASE REVIEW IT CAREFULLY. In this notice we use the terms "we," "us," "our," and "Kaiser Permanente" to describe the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region. For more details, please refer to section IV of this notice. I. What is "Protected Health Information?" Your protected health information (PHI) is individually identifiable health information, including demographic information, about your past, present or future physical or mental health or condition, health care services you receive, and past, present or future payment for your health care. Demographic information means information such as your name, social security number, address, and date of birth. PHI may be in oral, written or electronic form. Examples of PHI include your medical record, claims record, enrollment or disenrollment information, and communications between you and your health care provider about your care. Your individually identifiable health information ceases to be PHI 50 years after your death. If you are a Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the Northwest member and also an employee of any Kaiser Permanente company, PHI does not include the health information in your employment records. II. About our responsibility to protect your PHI By law, we must 1. protect the privacy of your PHI; 2. tell you about your rights and our legal duties with respect to your PHI; 3. notify you if there is a breach of your unsecured PHI; and 4. -

Alternatives to Acute Care

Alternatives to Acute Care July 1996 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Carolyn DeCoster, RN, MBA Sandra Peterson, MSc Paul Kasian, MD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts and expertise t~at many individuals contributed in completing this project and producing this report. We thank the following, and apologize in advance for anybody that we might have overlooked: • the health records staff and management of the 26 hospitals who participated in the study, with special thanks to Health Sciences Centre and St. Boniface General Hospital for assisting with the training of our abstractors; • the Health Services Utilization and Research Commission of Saskatchewan, especially Stewart McMillan, Steven Lewis and Joanne Hader, who generously shared applications of the InterQual methodology which they had developed and provided hours of support during our fieldwork and data analysis; • Charles Burchill for programming support in selecting the sample; • Drs. Brian Postl, Bryan Kirk, Ahmed Abdoh and Milton Tenenbein who reviewed the InterQual criteria; • the data abstractors: Dawna Bieniarz, Lonni Cruickshank, Sandy Gessler, Fran Home, Kay Linquist, Diane Mee, Nan Ouimet and Trish Rawsthome; • Marlyn Gregoire for data entry; • Keumhee Chough Carriere and Robert B. Tate for their statistical advice; • individuals who provided feedback on an earlier draft of this report: Noralou Roos, Evelyn Shapiro, Marian Shanahan and Mami Brownell; • Carole Ouelette, Linda Henderson and Trish Franklin who provided secretarial and administrative support; • the study Working Group: • Marylin Allen, RN, Director of Resident Care, Fred Douglas Lodge (member since March 1995) • Ross Brown, MD, Vice-President Medicine, St. -

Twenty-Four/Sevenoctober 18, 2010 Volume 5, Issue 23

October 18, 2010 Volume 5, Issue 23 CLARKtwenty-four/seven CLARKtwenty-four/seven Table of Contents October 18, 2010 Notes from the Smiles All Around Meet Your New Upcoming Events 2 Summit White 5 Dental Hygiene 7 Ambassadors! 12 House Summit on Anniversary Student Community Colleges Ambassadors From the HR A Voice from History 13 Department Breakfast for 6 David Hilliard speaks Penguin Patter 3 Champions on Black Panthers 10 News about people Advisory Committee from throughout the recognition Penguin Nation! Cover: Dean of Health Sciences Blake Bowers 2 and Associate Director of Instructional Operations Dedra Daehn attend the Advisory Committee Recognition Breakfast on Friday, October 15. 5 14 3 1 Notes from the Summit Clark hosts webcast of first-ever White House Summit on Community Colleges. “Community colleges are the unsung heroes of higher education.” That was a key message as President Obama convened the first White House Summit on Community Colleges on Tuesday, October 5. The event was led by Dr. Jill Biden, who has been a community college professor for 17 years. Among the highlights: • The administration has announced a new partnership called “Skills for America’s Future.” It’s designed to change the way business and labor leaders connect to community colleges. • President Obama has set a goal for America to once again lead the world in producing college graduates by 2020. That includes an additional 5 million community college degrees and certificates in the next 10 years. • The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation are launching the “Completion by Design” program. Investing $35 million over five years, the program hopes In a phrase that has special meaning at Clark College, two of the speakers— to dramatically improve graduation rates at community colleges. -

Kaiser Permanente Find Your Healthy Place

2021 Enrollment | California Find your healthy place With care designed to help you thrive kp.org/thrive Primary care Health Specialty plan care Digital care Pharmacy options and labs Connected care makes your life easier We combine care and coverage — which makes us different than your other health care options. Your doctors, hospitals, and health plan work together to make getting the right care more convenient. Your care meets you where you are, because it’s centered around you. 2 Benefit Summary 603910 UNITE HERE HEALTH - NCAL Principal Benefits for Kaiser Permanente Traditional HMO Plan (1/1/21—12/31/21) Accumulation Period The Accumulation Period for this plan is January 1 through December 31. Out-of-Pocket Maximum(s) and Deductible(s) For Services that apply to the Plan Out-of-Pocket Maximum, you will not pay any more Cost Share for the rest of the Accumulation Period once you have reached the amounts listed below. Family Coverage Family Coverage Self-Only Coverage Amounts Per Accumulation Period Each Member in a Family of Entire Family of two or more (a Family of one Member) two or more Members Members Plan Out-of-Pocket Maximum $2,000 $2,000 $4,000 Plan Deductible None None None Drug Deductible None None None Professional Services (Plan Provider office visits) You Pay Most Primary Care Visits and most Non-Physician Specialist Visits .......................... $20 per visit Most Physician Specialist Visits................................................................................. $20 per visit Routine physical maintenance exams, including well-woman exams ........................ No charge Well-child preventive exams (through age 23 months) .............................................. No charge Family planning counseling and consultations.......................................................... -

2017/2018 Annual Report

2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Annual Report 092718.indd 1 10/1/18 10:02 AM The 2017 – 2018 fiscal year has proven to be Oakland Parks and Recreation Foundation’s most productive to-date. Though the effective leadership of our Executive Director, Ken Lupoff, as well as the tireless work of our board members, the Foundation hit some major milestones this past year. One of our major accomplishments was with our 15th Annual A Taste of Spring in April. Through diligent work and effective planning, we were able to not only hold the event at the Oakland Museum of California for the first time, but also produced record net revenue for our signature event. It proved to be a special evening with a room full of great energy. We sincerely thank all who were able to join us at this year’s A Taste of Spring and we appreciate the generosity of our attendees. As the Foundation is always working on creative ways to fundraise, we recently started holding private house parties which are designed to introduce Oakland Parks and Recreation Foundation to potential new supporters. This new venture has been a true success, and we are currently planning our next party as well as others over the course of the next year. On the volunteerism front, we have really stepped up our game! Led by our Vice President and Volunteerism Committee Chair, Liz Westbrook, our volunteer work has grown in scope over the past year, as we now typically conduct three to four solid work days per year. -

2016 Community Health Needs Assessment

2016 Community Health Needs Assessment Kaiser Foundation Hospital – Oakland and Kaiser Foundation Hospital – Richmond License #140000052 Approved by KFH Board of Directors September 21, 2016 To provide feedback about this Community Health Needs Assessment, email [email protected] i KAISER PERMANENTE NORTHERN CALIFORNIA REGION COMMUNITY BENEFIT CHNA REPORT FOR KFH-OAKLAND AND KFH-RICHMOND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Applied Survey Research (ASR) on behalf of the hospitals listed in this report. ASR gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following individuals: Diana Camacho, John Muir Health Molly Bergstrom, Kaiser Permanente – Diablo Area Jean Nudelman, Kaiser Permanente – East Bay Area Debra Lambert, Kaiser Permanente – Greater Southern Alameda Area Michael Cobb, St. Rose Hospital Sue Fairbanks, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Karen Reid, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Tim Traver, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Denise Bouillerce, Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare Shelby Salonga, Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare Adam Davis, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland Lucy Hernandez, Washington Hospital Healthcare System Ruth Traylor, Washington Hospital Healthcare System ASR is also pleased to acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: Dale Ainsworth, California State University, Sacramento Marianne Balin, Kaiser Permanente – Diablo Area Debi Ford, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Susan Miranda, Kaiser Permanente – Greater Southern Alameda Area Dana Williamson, -

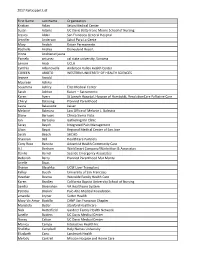

2017 Participant List First Name Last Name Organization Kristian Aclan

2017 Participant List First Name Last Name Organization Kristian Aclan Seton Medical Center Susan Adams UC Davis Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing Jessica Aldaz San Francisco General Hospital Jennifer Anderson Salud Para La Gente Mary Andich Kaiser Permanente Rochelle Andres Disneyland Resort Irinna Andrianarijaona Pamela antunez cal state university, Sonoma Lenore Arab UCLA Cynthia Arbanovella Anderson Valley Health Center COREEN ARIOTO WESTERN UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES Jeanne Arnold Maureen Ashiku Sosamma Ashley Elite Medical Center Sarah Ashton Kaiser -- Sacramento Karen Ayers St Joseph Hospital, Hospice of Humboldt, ResolutionCare Palliative Care Cheryl Balaoing Planned Parenthood Laura Balassone kaiser Melanie Balestra Law Office of Melanie L. Balestra Diane Barrows Clinica Sierra Vista Jan Bartuska Gathering Inn Clinic Seray Bayoh Integrated Pain Management Lilian Bayot Regional Medical Center of San Jose Sarah Beach SHCHD Shannon Bell HealthCare Partners Cony Rose Bencito Adventist Health Community Care A.J. Benham WorkSmart Company/Warbritton & Associates Danilo Bernal Seaside Emergency Associates Deborah Berry Planned Parenthood Mar Monte Arielle Bivas Sharon Blaschka UCSF Liver Transplant Kelley Booth University of San Francisco Heather Bosma Westside Family Health Care Karen Bradley California Baptist University School of Nursing Sandra Bresnahan VA Healthcare System Patricia Briskin` Palo Alto Medical Foundation amanda bryner Sutter Health Mary Vic Amor Bustillo CANP San Francisco Chapter Maristela Butler Stanford Healthcare -

RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2000 RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets Willard Largent Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Largent, Willard, "RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets" (2000). Purdue University Press Books. 9. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks/9 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. RAF Wings over Florida RAF Wings over Florida Memories of World War II British Air Cadets DE Will Largent Edited by Tod Roberts Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright q 2000 by Purdue University. First printing in paperback, 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-992-2 Epub ISBN: 978-1-55753-993-9 Epdf ISBN: 978-1-61249-138-7 The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier hardcover edition as follows: Largent, Willard. RAF wings over Florida : memories of World War II British air cadets / Will Largent. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55753-203-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Largent, Willard. 2. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, British. 3. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, American. 4. Riddle Field (Fla.) 5. Carlstrom Field (Fla.) 6. World War, 1939±1945ÐPersonal narratives, British. 7. Great Britain. Royal Air ForceÐBiography. I. -

2018 Leapfrog Top General Hospitals

2018 LEAPFROG TOP GENERAL HOSPITALS California Illinois Riverview Medical Center Inland Valley Medical Center Elmhurst Memorial Hospital Inspira Medical Center Woodbury Kaiser Foundation Hospital - Antioch Northwestern Medicine Delnor Rancho Springs Medical Center Hospital Pennsylvania Sequoia Hospital UPMC East Kaiser Foundation Hospital - San Louisiana Leandro St. Charles Parish Hospital Tennessee Adventist Health – Bakersfield TriStar Southern Hills Medical Center Massachusetts Florida Holy Family Hospital at Merrimack Texas Florida Hospital Apopka Valley Methodist Richardson Medical Center Jupiter Medical Center Saint Anne's Hospital Medical City Denton Florida Hospital Zephyrhills Kingwood Medical Center Florida Hospital Wesley Chapel Nevada CHRISTUS Mother Frances Hospital – Florida Hospital Carrollwood Henderson Hospital Tyler Orlando Health Dr. P. Phillips Hospital St. Mary's Regional Medical Center of Memorial Hospital West Reno Virginia Lawnwood Regional Medical Center & Inova Alexandria Hospital Heart Institute New Jersey Bon Secours Mary Immaculate Memorial Hospital Miramar Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Florida Hospital Heartland Medical Hospital at Hamilton Center Bayshore Medical Center 2018 LEAPFROG TOP CHILDREN’S HOSPITALS Arizona Florida Texas Phoenix Children’s Hospital Golisano Children’s Hospital of Children’s Health - Children’s Medical Southwest Florida Center Plano California Wolfson Children’s Hospital Texas Children’s Hospital West Loma Linda University Children’s Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Campus -

Gal Gadot Wears the Legendary Tiffany &

Gal Gadot Wears the Legendary Tiffany & Co. Elsa Peretti® Bone Cuff in her New Film, Wonder Woman 1984, in Theaters and Streaming on HBO Max December 25 | 1 Official Trailer, Wonder Woman 1984 Wonder Woman 1984 premieres Christmas Day and features Gal Gadot reprising her iconic role as Wonder Woman and alter ego Diana Prince. In the Patty Jenkins directed film, Gadot, as Prince, is wardrobed in the legendary Tiffany & Co. Elsa Peretti® Bone cuff in 18k yellow gold, a nod to Wonder Woman’s indestructible cuffs and a tribute to Prince’s real self—a hero. “Elsa Peretti® Bone cuff is still, to this day, the most stunning piece of jewelry that I’ve ever seen. I first became aware of this work of beauty when I received a small one as a gift from an ex’s mother. I loved it immediately, but even still, many years later when I glimpsed an editorial shot of someone wearing the long Bone cuff online, I didn’t realize it was related, and obsessively searched for what it was. When I found out it was Peretti’s extended cuff, it sealed the collection as a masterwork of adornment. My love of the cuffs became magically relevant when I directed the Wonder Woman films, as they marry perfectly with the character. As a result, we featured them as the one piece of jewelry that Diana Prince would choose in Wonder Woman 1984. It looks absolutely stunning on her, and I can’t wait for the world to see it featured in that way.” — Patty Jenkins The groundbreaking Elsa Peretti® design was introduced 50 years ago and perfectly contours to the wrist, showcasing the ergonomic sensuality that informs all of Peretti’s Tiffany & Co. -

Academic Catalog

Kaiser Permanente School of Allied Health Sciences 2020 Academic Catalog Effective Dates: January 1, 2020 – December 31, 2020 2020 Academic Catalog (v.2020-09-21) p. 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 About this Catalog ......................................................................................................................................... 4 General Information ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Mission, Vision, Values Statements .............................................................................................................. 6 Public Good Statement ................................................................................................................................. 7 Institutional Learning Outcomes................................................................................................................... 7 Accreditation and Approvals ......................................................................................................................... 8 Facilities and Equipment ............................................................................................................................. 10 General Education ......................................................................................................................................