A Collection of Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA

4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA In the Light of What We Know Zia Haider Rahman (http://granta.com/search/Zia+Haider+Rahman/) http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 1/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA Our concern with history, so Hilary’s thesis ran, is a concern with pre-formed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere, away from it all, somewhere as yet undiscovered. – W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz In the early hours of one September morning in 2008, there appeared on the doorstep of our home in South Kensington a brown-skinned man, haggard and gaunt, the ridges of his cheekbones set above an unkempt beard. He was in his late forties or early fifties, I thought, and stood at six foot or so, about an inch shorter than me. He wore a Berghaus jacket whose Velcro straps hung about unclasped and whose sleeves stopped short of his wrists, revealing a strip of paler skin above his right hand where he might once have worn a watch. His weathered hiking boots http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 2/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA were fastened with unmatching laces, and from the bulging pockets of his cargo pants the edges of unidentifiable objects peeked out. He wore a small backpack, and a canvas duffel bag rested on one end against the doorway. The man appeared to be in a state of some agitation, speaking, as he was, not incoherently but with a strident earnestness and evidently without regard for introductions, as if he were resuming a broken conversation. -

AMERICAN LITERARY MINIMALISM by ROBERT CHARLES

AMERICAN LITERARY MINIMALISM by ROBERT CHARLES CLARK (Under the Direction of James Nagel) ABSTRACT American Literary Minimalism stands as an important yet misunderstood stylistic movement. It is an extension of aesthetics established by a diverse group of authors active in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that includes Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, and Ezra Pound. Works within the tradition reflect several qualities: the prose is “spare” and “clean”; important plot details are often omitted or left out; practitioners tend to excise material during the editing process; and stories tend to be about “common people” as opposed to the powerful and aristocratic. While these descriptors and the many others that have been posited over the years are in some ways helpful, the mode remains poorly defined. The core idea that differentiates American Minimalism from other movements is that prose and poetry should be extremely efficient, allusive, and implicative. The language in this type of fiction tends to be simple and direct. Narrators do not often use ornate adjectives and rarely offer effusive descriptions of scenery or extensive detail about characters’ backgrounds. Because authors tend to use few words, each is invested with a heightened sense of interpretive significance. Allusion and implication by omission are often employed as a means to compensate for limited exposition, to add depth to stories that on the surface may seem superficial or incomplete. Despite being scattered among eleven decades, American Minimalists share a common aesthetic. They were not so much enamored with the idea that “less is more” but that it is possible to write compact prose that still achieves depth of setting, characterization, and plot without including long passages of exposition. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Big Baby Crime Spree and Other Delusions A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 by Darrin Michael Doyle B.A. Western Michigan University, 1996 M.F.A. Western Michigan University, 1999 Committee Chair: Brock Clarke, Ph.D. The Big Baby Crime Spree and Other Delusions: Short Stories Darrin Doyle Dissertation Abstract My creative work focuses on the notion of belief – not religious belief, necessarily, but belief (mistaken or not) in our ability to control the circumstances that shape us: as Wallace Stevens wrote, “It is the belief and not the god that counts.” Thematically, my works feature the following characteristics: elements of the fantastic; dark humor; and working-class protagonists who seek to palliate some unnamable dissatisfaction in their lives and who seek this correction through obsessive behavior that might be either wonderfully healing or terribly misguided – the results are in the eye of the beholder. The tensions between the fantastic and the realistic, between blue-collar and academic concerns, between knowing and not-knowing, between what we internally perceive and the external truth – unresolved oppositions like these are what create the lasting effects of literature, and they are what I strive to cultivate in my writing. -

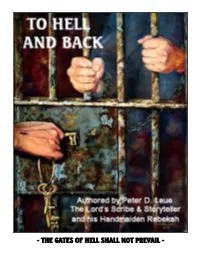

The Gates of Hell Shall Not Prevail

- THE GATES OF HELL SHALL NOT PREVAIL - ii FOREWORD In 1983 Peter and Rebekah Laue self-published a book titled: The Wood Blossom – A Search for Sanity in an Insensitive World. At that time 1,500 copies were printed and distributed over the next few years until the supply was exhausted. Their friend Mary Scott read one of the ten manuscripts that were circulated in hopes of finding a publisher who would risk publishing a book by an unknown author. No publisher came forward at that time. Mary Scott offered to sell her stocks so that the book could be published as soon as possible. Peter and Rebekah gratefully accepted the offer. Mary loves to give books she considers valuable as Christmas presents and chose to give one hundred copies to friends and family beginning with Christmas of 1983. FRONT & BACK COVERS OF THE FIRST EDITION The above title and cover is certainly a far cry from the new title but very appropriate as seen from the vantage point of 25 years later. The fact that the writer is now living in a beautiful log cabin on Lake Pagosa with his handmaiden Rebekah and is not incarcerated in a prison or mental institution is only by God’s grace. The fact that he did not succumb to voices and iii suggestions that were from the pit of hell, is a matter of God’s grace. The fact that he is not subdued by medication to corral the extremes in his personality is a matter of God’s grace. The fact that the mortgage on Peter and Rebekah’s home was paid off seventeen years ahead of schedule is a matter of God’s grace. -

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P. E. 5772 - 15 Caught Up In You .38 Special 5816 - 08 Hold On Loosely .38 Special 5772 - 08 If I'd Been The One .38 Special 5950 - 06 Second Chance .38 Special 4998 - 05 Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation 4998 - 06 While We're Young 1 Girl Nation 5915 - 18 Beautiful 10 Years 5881 - 11 Through The Iris 10 Years 6085 - 15 Wasteland 10 Years 5459 - 07 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 5218 - 08 Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs 1046A -08 These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs 5246 - 14 I'm Not In Love 10cc 6274 - 20 Things We Do For Love, The 10cc 5541 - 04 Cupid 112 5449 - 10 Dance With Me 112 5865 - 18 Peaches And Cream 112 5883 - 04 Right Here For You 112 6037 - 07 U Already Know 112 5790 - 02 Hot And Wet 112 & Ludacris 5689 - 04 Na Na Na 112 & Super Cat 5431 - 05 We Are One 12 Stones 5210 - 20 Chocolate 1975, The 6386 - 01 If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 1975, The 5771 - 18 Love Me 1975, The 6371 - 08 Me And You Together Song (Clean) 1975, The 6070 - 19 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 1975, The 5678 - 02 I'm Different (Clean) 2 Chainz 5673 - 05 No Lie (Clean) 2 Chainz & Drake 5663 - 12 Birthday Song (Clean) 2 Chainz & Kanye West 5064 - 20 Feds Watching (Clean) 2 Chainz & Pharrell 5450 - 20 We Own It 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa 5293 - 09 I Do It (Clean) 2 Chainz Feat. -

The Current Volume 29 : Issue 5

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 9-11-2018 The urC rent Volume 29 : Issue 5 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The urC rent Volume 29 : Issue 5" (2018). The Current. 677. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/677 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Student-Run Newspaper of Nova Southeastern University September 11, 2018 | Vol. 29, Issue 5 | nsucurrent.nova.edu Features Arts & Entertainment Sports Opinions Read this before you get a piercing Enjoy Fall themed snacks without The USSF needs to be more The whiteboards are a mess P. 4 P. 7 the pumpkin-spice P. 9 invested P. 10 The Incoming Class of 2022 and future plans for recruitment By: Christina McLaughlin Opinions Editor For this incoming class, the university set a be engaged and be involved on campus,” said students through their college experience the “The intimate learning environment is strategic goal to accept 1,150 first time in college DeNapoli. undergraduate admissions staff believes that integral to the learning environment to all the (FTIC) freshman. Now, those numbers are According to Peter Littlefield, associate the new NSU brand campaign will encourage programs that we promote here,” said Littlefield. confirmed with a grand total of 1,563 including dean of undergraduate admissions, the more students to make NSU one of their top choices The first year seminar course for this year 300 transfers, and 1,271 FTIC students. -

Indie Folk Chill Nostálgica

Hitzzz NACIONAIS A/I NACIONAIS J/Z INTERNACIONAIS A/I INTERNACIONAIS J/Z ROCK BR ROCK SERTANEJAS SERTANEJO RAIZ COUNTRY BLUES . JAZZZ BLUES BRASILEIRO BOSSA NOVA FESTA MPB… VERSÕES BR VERSÕES MUNDO LATINAS L´AMOUR (FRENCH) VINTAGE CAFÉ . BOSSA LOUGE POS-PUNK & NEW WAVE L`ESSENZIALE (ITALIAN) FADO + CLUB . DANCE . ELETRONIC HOUSE LOUNGE POP RISING REMIX BR H O T PIANO & TRAPSOUL REGGAE ROOTS . BREGA LOVE . FORRÓ . + FUNK +SAMBA BLOCO DA FAVORITA (CARNAVRAU) TRILHAS HEY YOU NA BAD JURASSIC PARK BR.EGA .JOVEM GUARDA GOSPEL HOTLIST MYSTICAL EXPERIENCE MEUS NÓS PEDIDOS 365 NETFILMES NA BATIDA . ZOUK . KIZ SEGURA ESSE ROCK ACOUSTIC PLAYLIST TRANSANTE ROAD TRIP NOVA MPB? SO SEXY NA GAITA DANCE CLASSICS (TOP 100) INDIE FOLK CHILL NOSTÁLGICA INDIE folk CHILL Procure Aqui! “Alabama Shakes Hold On” 00:00 00:00 1. “Alabama Shakes Hold On” 3:48 2. “Alt J Breezeblocks” 3:47 3. “Alt-J Dancing In The Moonlight” 2:36 4. “Amos Lee Hang On, Hang On” 4:09 5. “Anderson East All On My Mind” 3:41 6. “Arctic Monkeys R U Mine” 3:21 7. “AURORA Half The World Away” 3:04 8. “Ben Howard Black Flies” 6:22 9. “Ben Howard Old Pine” 5:34 10. “Ben Howard Only Love” 3:53 11. “Ben Howard Promise” 6:18 12. “Blitzen Trapper Furr” 4:08 13. “Birdy People Help The People” 4:17 14. “Bon Iver Skinny Love” 3:58 15. “Cage the Elephant Cigarette Daydreams” 3:28 16. “Charlotte Lawrence, Nina Nesbitt, Sasha Sloan - Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” 2:43 17. “Christine and the Queens Ordinary Love” 3:49 18. -

Grammar and Language Workbook, Part 1

Grammar Grammar 45 Name ___________________________________________________ Class _________ Date ____________________ Unit 1: Subjects, Predicates, and Sentences Lesson 1 Kinds of Sentences: Declarative and Interrogative A sentence is a group of words that expresses a complete thought. All sentences begin with a capital letter and end with a punctuation mark. Different kinds of sentences have different purposes. A declarative sentence makes a statement. It ends with a period. Grammar Last summer I went on a long trip. An interrogative sentence asks a question. It ends with a question mark. Where did you go on your vacation? Exercise 1 Insert a period if the sentence is declarative. Insert a question mark if it is interrogative. My family and I went to Alaska . 1. Have you ever been that far north ? 2. Alaska is a wonderful and wild state . 3. Isn’t it the largest state in the union ? 4. Was the weather hotter than you expected ? 5. Some days were so warm that I wore shorts . 6. In some parts of Alaska, the sun never sets in summer . 7. Summers in Alaska don’t last very long . 8. Are Alaskan winters as cold as they say ? 9. The ground under much of Alaska is permanently frozen . 10. How can animals live in such a cold climate ? Copyright © by Glencoe/McGraw-Hill 11. All the animals in Alaska are equipped for the cold . 12. Did you see any bears in Alaska ? 13. We saw a lot of brown bears at Katmai National Monument . Unit 1, Subjects, Predicates, and Sentences 47 Name ___________________________________________________ Class _________ Date ____________________ 14. -

Artist Track 070 Shake Mirrors 1010 Benja SL Ultimaybe 380 Crew Yaegl Birrinba 6LACK Cutting Ties 6LACK East Atlanta Love Letter {Ft

Artist Track 070 Shake Mirrors 1010 Benja SL Ultimaybe 380 Crew Yaegl Birrinba 6LACK Cutting Ties 6LACK East Atlanta Love Letter {Ft. Future} 6LACK Let Her Go 6LACK Loaded Gun 6LACK Nonchalant 6LACK Pretty Little Fears {Ft. J. Cole} 6LACK Switch 88rising & Rich Brian History 88rising, Joji & BlocBoy JB Peach Jam 88rising, Joji, Rich Brian, Higher Brothers, Midsummer Madness AUGUST 08 A Perfect Circle Delicious A Perfect Circle So Long, And Thanks For All The Fish A Perfect Circle TalkTalk A$AP Ferg Harlem Anthem A$AP Rocky (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay {triple j Like A Version 2018} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./ Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Bad Company {Ft. BlocBoy JB} A$AP Rocky Brotha Man {Ft. French Montana} A$AP Rocky Fukk Sleep {Ft. FKA Twigs} A$AP Rocky Praise The Lord (Da Shine) {Ft. Skepta} A$AP Rocky Sundress A$AP Rocky Tony Tone A$AP Rocky x Gucci Mane x 21 Savage Cocky {Ft. London On Da Track} A. Swayze & The Ghosts Suddenly A.B. Original BLACCOUT Ab-Soul, Anderson .Paak & James Blake Bloody Waters Aburden One For You Aburden To The Sky Adrian Eagle 17 Again Adult.Films School.Night AFI Get Dark After Touch Six Feet Closer After Touch Use Me Ainslie Wills Society Airways Alien AJ Tracey Doing It Ajax I'm Hot Akouo So Long Akurei August {Ft. Golden Vessel} Akurei Ride Home Albert Hammond Jr. Far Away Truths Alex the Astronaut Happy Song Alex The Astronaut Waste Of Time Alexander Biggs Car Ride Alexander Biggs Close Enough Alice Glass Mine Alice In Chains Red Giant Alice Ivy American Boy {triple j Like A Version 2018} Alice Ivy Bella Alice Ivy Charlie Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Carla Keaton Tempe Artist

Table Of Contents “From The Ashes,” “The Gift,” “New Magic,” “Oceans and Fiction Dreams,” “Iris” – Susan Canasi ...........................................37-41 “Transformation” – Fran P. Harris ........................................9-16 “Aureole of Night,” “Fairy-Land,” “Sand Dunes,” “Bead “The Stain” – Andrew J. Hogan ............................................35-36 Symphony,” “Sultry Day,” “Wedding Set Expectation” “A Better Life,” “A Creative Cycle,” “We Felt Together” – Lana May ............................................................................58-63 – Alie Vallon ............................................................................48-57 “Stone Cold” – J. Michael Green .........................................80-81 “Rusted Junk ” – Eduardo Cerviño ......................................82-83 News Coming Oct. 26: Annual Fall Festival of the Arts ......................8 Friday Night Writes ....................................................................84 All about The Arizona Consortium for the Arts ...................... 85 Non-Fiction Open Mic: A celebration of the arts ......................................... 85 “Through All Windows” – Maya L. Kapoor ............................7-8 The Consortium’s vision for a multicultural arts center ........86 “Birding Without Fear” – Cathy Rosenberg ........................33-34 Calls to writers, artists for Blue Guitar Jr. ..........................87-88 Call to poets for Summer 2014 issue of Unstrung ....................89 The Blue Guitar magazine staff biographies