Chicago's Video Surveillance Cameras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relationship Between Kinetics of Countermovement Jump and Proximal Mechanics of Collegiate Baseball Pitching

Louisiana Tech University Louisiana Tech Digital Commons Master's Theses Graduate School Spring 5-2021 Relationship between Kinetics of Countermovement Jump and Proximal Mechanics of Collegiate Baseball Pitching Motoki Sakurai Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.latech.edu/theses Part of the Kinesiology Commons RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN KINETICS OF COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP AND PROXIMAL MECHANICS OF COLLEGIATE BASEBALL PITCHING by Motoki Sakurai, B.S. A Thesis Presented in Parital Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Kinesiology COLLEGE OF EDUCATION LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY May 2021 ABSTRACT Purpose: To identify how countermovement jump (CMJ) kinetics influence kinematics and momentum of the baseball pitching motion with a focus on lower body and proximal movement. Methods: Nineteen Division I collegiate pitchers (age = 19.9 ± 1.5 years; height = 1.86 ± 0.06 m; weight = 90.7 ± 13.8 kg) performed a bilateral CMJ test and threw 5 strike fastballs from the stretch with a slide step on a custom-made pitching mound built for a laboratory setting. A 3D motion capture system tracked whole-body kinematics at 240 Hz from 29 reflective markers. Two force plates recorded ground reaction forces (GRFs) from each leg at 1040 Hz during both jump test and pitching captures. A one-way ANOVA separating high and low fastball velocity groups by an athlete’s median performance identified differences in pitching mechanics and jump kinetic variables. Meaningful differences between the variables were determined by cohen’s d effect size with 95% confidence intervals. The same statistical calculations were repeated to identify differences in pitching mechanics and jump kinetic variables between two groups, split based on the medians of pitchers’ total linear momentum in anterior-posterior direction. -

Mccormick Place Lakeside Center Brochure

LAKESIDE CENTER LAKESIDE CENTER MEETING ROOMS LEVEL 2 LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 LEVEL 3 Room Sq. Ft. Dimensions Ceiling Height Theater School Room Banquet E250 966 36' 9" x 25' 8" 10' 0" † – – E251 955 36' 8" x 25' 5" 12' 0" 50 48 48 Dock Door C1 E252 2,289 40' 8" x 56' 1" 12' 1" 50 48 48 Roll Up Doors 3-10 E253 6,678 53' 1" x 126' 0" 13' 11" 744 333 384 E253a 1,840 53' 1" x 36' 0" 13' 11" 189 90 80 Dock Doors A - F E253b 1,612 53' 1" x 30' 0" 13' 11" 173 78 64 Dock Dock E253c 1,612 53' 1" x 30' 0" 13' 11" 173 78 64 Freight Door Doors Doors 29' 0" 29' 0" E253d 1,613 53' 1" x 30' 0" 13' 11" 173 78 64 29' 0" 29' 0" B3-B9 D1-D7 To E254 1,190 49' 4" x 22' 6" 8' 4" † – – Soldier Field Parking E255 1,439 57' 1" x 25' 2" 14' 1" 153 72 56 E256 1,445 57' 7" x 25' 0" 14' 1" 153 72 56 EF 2 Gate 34 Gate 35 E257 1,214 49' 1" x 22' 7" 12' 0" 50 48 40 EF 1 EF2 EF1 Roll Up Roll Up E258 2,718 56' 1" x 48' 4" 11' 11" 252 135 128 Level One Area Loading Dock Door 2 Door 11 EF1 E259 1,353 51' 9" x 26' 0" 12' 0" 138 60 64 Roll Up Door G EF2 LEVEL 4 E260 1,034 39' 6" x 26' 1" 12' 0" 102 51 40 E261 1,032 39' 7" x 26' 0" 12' 0" 102 51 40 Hall D E262 1,039 39' 8" x 26' 1" 12' 0" 102 51 40 Gate 33 Dock Hall E 300,000 sq. -

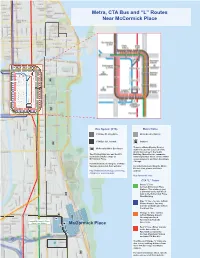

Metra, CTA Bus and “L” Routes Near Mccormick Place

Metra, CTA Bus and “L” Routes Near McCormick Place Bus System (CTA) Metra Trains CTA Bus #3, King Drive Metra Electric District CTA Bus #21, Cermak Stations There is a Metra Electric District McCormick Place Bus Stops station located on Level 2.5 of the Grand Concourse in the South The #3 King Drive bus and the #21 Building. Metra Electric commuter Cermak bus makes stops at railroad provides direct service within McCormick Place. seven minutes to and from downtown Chicago. For information on riding the CTA Bus System, please visit their website: For information on riding the Metra Electric Line, please visit their http://www.transitchicago.com/riding_ website: cta/service_overview.aspx http://metrarail.com/ CTA “L” Trains Green “L” line Cermak-McCormick Place Station - This station is just a short two and a half block walk to the McCormick Place West Building Blue “L” line - Service to/from O’Hare Airport. You may transfer at Clark/Lake to/from the Green line. Orange “L” line - Service to/from Midway Airport. You may transfer at Roosevelt to/from the Cermak-McCormick Place Green Line. Green Line Station McCormick Place Red “L” line - Either transfer to the Green Line at Roosevelt or exit at the Cermak-Chinatown Station and take CTA Bus #21 The Blue and Orange “L” trains are also in easy walking distance from most CTA Bus stops and Metra stations. For more information about specific routes, please visit their website:. -

Blue Devils Meet Anderson in First Home Tilt Satans to Play Toughest S.H.S

OUR FIFTIETH YEAR OF CONTINUOUS DAILY PUBLICATION! SHORTRIDGE DAILY ECHO VOL. L, No. 17 SHORTRIDGE HIGH SCHOOL, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA. FRIDAY, OCT. 3, 1947. 3 CENTS BLUE DEVILS MEET ANDERSON IN FIRST HOME TILT SATANS TO PLAY TOUGHEST S.H.S. DELEGATES BULLETIN OPPONENT YET SCHEDULED TO ATTEND PURDUE Class of 1949 junior officers were elected as follows: Kick-off Time 2:30 P.M. at 43rd Street Field; CONFERENCE President—Dick Hall. Encounter Last Contest Before Devils Meet Vice - President — Barbara First City Opponent, Washington Bloor Redding, Kathy Oweri, Redding. James MerreU, Darcy DeWeese, Secretary—Jane Nickell. j The Shortridge Blue Devils will Junior President to Meet Treasurer—Dan Nyhart. Philateron Club to swing into action again Friday aft Vaudeville Chairman—Mar ernoon when they raise the curtain Five Shortridge students and Mrs. garet Faye Hannon. Distribute Grid Programs with their flrst home game against Eugenia Hayden, sponsor, will at Program Editor—Joan Dun One of the projects of the Phila Anderson at the Shortridge field. tend the High School Leaders' con ham. teron Club this season is that of Kick-off time will be 2:30 p.m. ference to be held at Purdue Uni giving cut programs at football This will mark the flrst major versity Monday, October 6. games. This plan will be inaugu test to the 1947 Blue Devil football Bloor Redding and Kathy Owen SELLING COURSE TO rated at the game Friday. Those team as they opened the season will represent the Student Board; BE OFFERED TO girls' who will participate are Mary against two breathers in Beech James Merrell, publications; Darcy STUDENT SALESMEN Bose, Jean Cooprider, Mary Carol Grove and Southport. -

2008 Annual Report || a Year in Review 11 Message from the Superintendent

C HI C AGO POLI C E D E P ARTMENT 2008 ANNUAL RE P ORT A YEAR IN REVIE W CITY OF CHI C AGO CHI C AGO POLI C E DE P ARTMENT RI C HAR D M. DALEY JO D Y P. WEIS MAYOR SU P ERINTEN D ENT OF POLI C E T HE 2008 ANNU A L REPO rt IS DEDIC at ED T O A LL T HE MEN A ND WOMEN OF T HE C HIC A GO POLICE DEP art MEN T WHO H A VE GIVEN T HEI R LIVES IN SE R VICE T O T HE CI T Y OF C HIC A GO A ND I T S R ESIDEN T S . Police Officer n July 2, 2008, at approximately 2:00 am, Officer Richard Francis Richard M. Francis wasO summoned to assist a city bus driver with a problematic passenger. While escorting the # 5276 unruly passenger off the bus, a scuffle ensued. The passenger was able to obtain control of the - 02 July 2008 - officer’s weapon and shot him several times, fatally wounding him. Officers responded to the scene and shot the woman several times in defense of the officer, critically wounding her. Officer Francis had been a proud member of the United States Navy who served his country on a combat patrol boat during the Vietnam War. He returned home to serve and protect the residents of this city as a Chicago Police Officer. For 27 years, Francis was a member of the Patrol Division and was most recently assigned to the Belmont (19th) District. -

The 2012 Budget Overview Document

City of Chicago Budget 2012 Overview Mayor Rahm Emanuel The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to the City of Chicago for its annual budget beginning January 1, 2011. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. 2012 Budget Overview Letter from the Mayor Dear Chicagoans, To protect the health and safety of all Chicagoans, strengthen communities and neighborhoods, foster a vibrant local economy, attract new jobs, and maintain and improve our infrastructure, the City must be in strong financial health. For the past decade, the City of Chicago has been budgeting in a way that is not sustainable. There has been a long-standing structural deficit as expenses grew at a faster rate than revenues. For the past few years, that budget gap has been closed through the use of rainy day funds. With this 2012 balanced budget proposal, we begin to end that practice by working to bring our expenses more in line with actual revenues and saving our rainy day funds for when they are truly needed. The City is facing economic and financial challenges that require real and meaningful changes to the way in which the City conducts its business. We must continue to provide the people of Chicago with quality services while working to improve the management and efficiency of government to keep those services affordable for Chicago’s taxpayers. -

Hilton Opens First Tri-Branded Hotel at Chicago's Mccormick Place

CONTACTS: Morgan Mark For First Hospitality Group, Inc. Phone +1 248-258-2333 [email protected] Jeanine Karp For Hilton Phone +1 305-785-0423 Jeanine.Karp@rbbcommunic ations.com Hilton Opens First Tri-Branded Hotel at Chicago’s McCormick Place Partners with First Hospitality Group to bring Combined Hilton Garden Inn, Hampton Inn by Hilton and Home2 Suites by Hilton to Chicagoland area CHICAGO and MCLEAN, VA – August 7, 2018 – Hilton (NYSE: HLT), along with First Hospitality Group, Inc. (FHG), today announced the opening of its newest hotel, the company’s first tri-branded property, which includes Hilton Garden Inn Chicago McCormick Place, Hampton Inn by Hilton Chicago McCormick Place and Home2 Suites by Hilton Chicago McCormick Place. Connected to McCormick Place, North America’s largest convention center, and adjacent to Wintrust Arena, the property is a one-of-kind addition to downtown Chicago’s South Loop and Motor Row District lodging offerings. The hotel also represents Hilton’s first tri-branded property, furthering the company’s leadership position in the development of multi-brand hotels. Hilton currently has a footprint of more than 85 open, multi-brand properties, with an even larger pipeline of multi-brand projects in development around the globe. “Hilton is passionate about delivering exceptional travel experiences and continually looking for opportunities to add value for our guests,” said Bill Duncan, Global Head, All Suites and Focused Service Category, Hilton. “This milestone tri-brand property embodies that spirit. -

Enriques Wants Stimulus Money for Shelter-Gym

Losalio, Ballo, Silva Take First in Talent Show The Kaʻū High & Middle School Talent Be, singing and playing electric guitar. show brought some 30 students to the stage on The Mandingos, comprised of Dillin Ballo and March 20, with Aaron Losalio taking first place Cameron Silva, took first in the group division. with his ʻukulele solo rendition of the Beatles The first place group and first place solo artist song, While My Guitar Gently Weeps. each won $100, second place $75 and third place The second place solo winner was Justin $50 from Kaʻū Music Workshops. All winners won Ramos, who played acoustic guitar and sang a scholarship to the Daniel Ho songwriting work- Hey There Delilah, made famous by the band shop to be held April 2-4 at Pāhala Plantation House Plain White Ts. in preparation for the Kaʻū Coffee Festival April 24- The third place solo winner was Rebecca 26. First Place Group The Mandigos with Dillin Ballo and Cameron Silva Zandenberg, who had been attending Kaʻū High First Place Soloist Robert Domingos and the Kaʻū School of the School for only a week. She performed Blessed Aaron Losalio Talent Show, pg. 7 Volume 7, Number 6 The Good News of Ka‘ū, Hawaiʻi April, 2009 Enriques Wants Stimulus Money for Shelter-Gym County Council member Guy En- for the building that could also include a said the shelter-gym would not only serve as well as hurricanes, earthquakes, floods riques flew to Washington, D.C. in March certified kitchen to serve the shelter and the community when it is completed, but and other disasters. -

Amended and Restated Banquet and Concessions Management Agreement

DocuSign Envelope ID: 4B34C561-C0C6-470E-985F-6CD740146C82 AMENDED AND RESTATED BANQUET AND CONCESSIONS MANAGEMENT AGREEMENT for McCORMICK PLACE CONVENTION CENTER, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS between the METROPOLITAN PIER AND EXPOSITION AUTHORITY and SMG FOOD AND BEVERAGE, LLC d/b/a SAVOR DATED: December 29, 2017 DocuSign Envelope ID: 4B34C561-C0C6-470E-985F-6CD740146C82 TABLE OF CONTENTS [UPDATE] ARTICLE I - INCORPORATION OF RECITALS, DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION............................................................................................................2 1.1 Incorporation of Recitals..........................................................................................2 1.2 Exhibits. ...................................................................................................................2 1.3 Definitions................................................................................................................2 1.4 Interpretation. .........................................................................................................10 1.5 Conflicting Provisions. ..........................................................................................10 ARTICLE II - ENGAGEMENT OF MANAGER; SCOPE OF SERVICES; RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES ........................................................................................................11 2.1 Engagement............................................................................................................11 ARTICLE III - Use of the Food Service Areas; Certain -

MONEY MAHA WORLD-HERALD BANKRUPTCIES BUILDING PERMITS Four Bankruptcy Categories Listed Cedar Bluffs, Neb., Chapter 7

6D • MONDAY, MAY 19, 2014OMONEY MAHA WORLD-HERALD BANKRUPTCIES BUILDING PERMITS Four bankruptcy categories listed Cedar Bluffs, Neb., Chapter 7. ing, Neb., Chapter 7. Amanda R. Swenson, 136 N. 30th Lisa C. Barrett, 345 Fletcher Ave., SINGLE-FAMILY DWELLINGS St., $38,650. are: Chapter 7, bankruptcy involv- St., Lincoln, Chapter 7. Lincoln, Chapter 7. Kristy L. Prine, 940 Lincoln St., Robert W. Penner, 755 Goldenrod Belt Construction Co. Inc., 1715 S. SFI Ltd. Partnership 14, 310 Regency ing liquidation of nonexempt as- Tecumseh, Neb., Chapter 7. Court, Crete, Neb., Chapter 13. Tyrece L. Willcoxon, 5125 Hunting- Laura C. Boardman, 159 Sheridan sets; Chapter 11, plan permitting 211th St., $191,736; 1508 S. 210th St., Parkway, $50,000. Sharon L. Strodtman, 520 A St., Tiffany S. Metteer, 454 13th Ave., ton Ave., Lincoln, Chapter 7. St., Gordon, Neb., Chapter 7. reorganization of fi nancial affairs $152,880. Western Crossing Investors, 10250 Lincoln, Chapter 7. Columbus, Neb., Chapter 7. Chris L. Denker, P.O. Box 832, Daniel R. Mars, 1615 W. Louise, under court supervision for an BHI Development Inc., 5809 S. 172nd St., Norfolk, Neb., Chapter 7. Grand Island, Neb., Chapter 7. Regency Circle, $30,000. individual engaged in business or Richard A. Rappa, 3815 South St., Nyazar C. Chagiy, 2238 Orchard $181,840. Lincoln, Chapter 7. St., Lincoln, Chapter 7. Florence M. Schmidt, P.O. Box 133, Kari L. Hernandez, 5018 Adams Westroads Mall LLC, 10000 California St., for a company (asset and liability BSR-FW LLC, 6029 S. 193rd Ave., $145,000. schedules are not always fi led with Tilden, Neb., Chapter 7. -

Downtown Transit Account on a Ventra Card Or Attraction Take Bus Or Train: North Michigan Avenue, and a Few Places Beyond

All Aboard! Buses Trains Fares* Quick Ride Guide Chicago Transit Authority This guide will show you how to use Chicago Transit Riding CTA Buses Riding CTA Trains Base/Regular Fares From the Loop 151511 SHERIDIDANAN Deducted from Transit Value in a Ventra Authority (CTA) buses and trains to see Downtown Chicago, CTA buses stop at bus shelters or signs Each rail line has a color name. All trains operate Downtown Transit Account on a Ventra Card or Attraction Take Bus or Train: North Michigan Avenue, and a few places beyond. that look like this. Signs list the service TOTO DEEVO VO NN daily until at least midnight, except the Purple Line Express (see contactless bankcard Full Reduced** Art Institute, Chicago Cultural Ctr. Short walk from most buses and all rail lines days/general hours, route number, name map for hours). Trains run every 7 to 10 minutes during the day ♦ The CTA runs buses and elevated/subway trains (the ‘L’) and destinations, and the direction of travel. and early evening, and every 10 to 15 minutes in later evening. ‘L’ train fare $2.25 $1.10 FirstMerit Bank Pavilion at 146 south on State or 130 (Memorial Day Northerly Island Park weekend thru Labor Day) east on Jackson that serve Chicago and 35 nearby suburbs. From Here’s a quick guide to boarding in the Downtown area: Bus fare† $2 $1 When a bus approaches, look at the sign Chinatown Red Line train (toward 95th/Dan Ryan) Downtown, travel to most attractions on one bus or train. 22 Clark above the windshield. -

PREIT Celebrates Another Milestone in the Redevelopment of Valley

CONTACT: Heather Crowell SVP, Strategy and Communications (215) 454-1241 [email protected] PREIT Celebrates Another Milestone in the Redevelopment of Valley Mall With the Opening of Onelife Fitness and Sears Replacement DICK’s Sporting Goods is the latest in-demand concept joining the tenant roster, replacing the defunct Sears store PREIT successfully replaces over 300,000 square feet of department store space at this property Philadelphia, PA, February 20, 2019 – PREIT (NYSE: PEI) today detailed new updates in the transformation of Valley Mall in Hagerstown, MD – one of the Company’s key suburban Washington DC assets. As part of its strategic efforts to strengthen its portfolio through anchor repositioning and remerchandising, PREIT has successfully replaced three department stores, with four tenants opening in just two years. Onelife Fitness and Tilt Earlier this month, Onelife Fitness opened its 70,000-square foot full-service gym, the brand’s fifth Maryland location. The facility offers a community-focused, amenity-driven club – including an extensive array of fitness classes, a cardio cinema and indoor and outdoor pools, further differentiating this property in the traditional mall landscape. Onelife Fitness joins Tilt Studio in the former Macy’s box with unique, experiential concepts. Tilt Studio – one of just 13 locations in the country – opened in September 2018, offering 48,000 square feet of attractions including rides, bowling, black light laser tag, black light golf and arcade games. Belk In October, Valley Mall welcomed the region’s first Belk, which occupies 123,000 square feet in the former Bon-Ton space. In July 2017, PREIT announced the proactive recapture and replacement of Bon- Ton, which closed in February 2018.