Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Authenticity of Ambiguity: Dada and Existentialism

THE AUTHENTICITY OF AMBIGUITY: DADA AND EXISTENTIALISM by ELIZABETH FRANCES BENJAMIN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham August 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii - ABSTRACT - Dada is often dismissed as an anti-art movement that engaged with a limited and merely destructive theoretical impetus. French Existentialism is often condemned for its perceived quietist implications. However, closer analysis reveals a preoccupation with philosophy in the former and with art in the latter. Neither was nonsensical or meaningless, but both reveal a rich individualist ethics aimed at the amelioration of the individual and society. It is through their combined analysis that we can view and productively utilise their alignment. Offering new critical aesthetic and philosophical approaches to Dada as a quintessential part of the European Avant-Garde, this thesis performs a reassessment of the movement as a form of (proto-)Existentialist philosophy. The thesis represents the first major comparative study of Dada and Existentialism, contributing a new perspective on Dada as a movement, a historical legacy, and a philosophical field of study. -

Issue No. 3, Vol 5, November 2010

Department of Vol. 5 - Issue No. 3 November 2, 2010 UPCOMING DEPARTMENT EVENTS Colloquium Series, 2010-11 Teresa Macias (University of Victoria) "Tortured Bodies": Speaking Terror and the Epistemic Violence of the Chilean Commission on Torture and Political Imprisonment Thursday, Nov. 4th 11:30-1:00, ANSO 134 CONGRATULATIONS Robin O'Day was one of six Ph.D. students selected from throughout Canada and Japan to participate in the full day Ph.D. dissertation workshop held in conjunction with the Japan Studies Association of Canada conference at UBC, on Sept. 29, 2010. Rafael Wainer was recognized as Co-Director for a 2010-2012 "Programa de Reconocimiento Institucional de Investigaciones de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales" (Program of Institutional Recognition for Research at the Faculty of Social Sciences) Faculty of Social Sciences - University of Buenos Aires: August 2010-August 2012. Alonso, Juan Pedro (director) and Wainer, Rafael Esteban (co-director). Organización profesional y experiencia del final de la vida. Un abordaje socio-antropológico de la enfermedad, el sufrimiento y el morir (Professional Organization and End of Life Experience: A Sociological- Anthropological Approach to Illness, Suffering, and Dying). Faculty of Social Sciences – University of Buenos Aires. Gino Germani Institute. Research Project R10-200. ANNOUNCEMENTS Works by Professor Nicola Levell and Dada Docot, along with multimedia works by twenty other artists and anthropologists, will be exhibited this year at the Ethnographic Terminalia, an event scheduled to coincide with the American Anthropological Association annual meetings in New Orleans. Kate Henessy is among the initiators and curators of this group/event. For more information, please visit http://ethnographicterminalia.org/ UBC ANTHROPOLOGY IN THE NEWS The Museum of Vancouver formally repatriated the iconic Sechelt Image, a two to three thousand years old 32 kilogram stone sculpture once featured by former anthropology department member Wilson Duff in his publication, Images, Stone B.C., to the Sechelt First Nation. -

Man Ray Im Urteil Der Zeitgenössischen Kunstliteratur

Man Ray im Urteil der zeitgenössischen Kunstliteratur unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des multimedialen Angebots Diplomarbeit im Fach Kunstwissenschaft und Kunstinformationswesen Studiengang Wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Corinna Herrmann Erstprüferin: Prof. Dr. Gudrun Calov Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Kuhlemann Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15. Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Die vorliegende Diplomarbeit behandelt das Werk Man Rays und die Auswirkungen seiner Arbeiten auf die heutige Zeit. Die einführende Kurzbiografie liefert einen Überblick über sein Leben. Es folgt die Darstellung seines Lebenswerks mit den Auswirkungen auf die moderne Kunst, insbesondere die Fotografie. Anschließend wird das Ausstellungswesen zu Man Ray untersucht. Die folgende Betrachtung der zeitgenössischen Kunstliteratur geht im besonderen auf das multimediale Angebot zu Man Ray ein. Den Abschluss bildet die Darstellung von Man Ray in der Öffentlichkeit anhand des Kunstmarkts und anhand seiner Werke in Museen und Artotheken. Schlagwörter: Man Ray, Fotografie, Kunstliteratur, Kunstmarkt, Neue Medien, Diplomarbeit Abstract This diploma thesis presents the work of Man Ray and discusses its influence on the world of art today. First, an overview of his life is given, followed by a description of his works and the effects on modern art and in particular on photography. Next, Man Ray’s exhibition will be examined. Some of the contemporary art literature is presented, -

MR-Livret Anglais-Grilledebase28 CO.Indd

MAN RAY fashion photographer INTRODUCTORY TEXT theatre art and the pictorial avant- garde. Composition, re-cropping, 01 the interplay of light and shadow, solarisation and colourisation Man Ray, fashion photographer are some of the innovations that Following the advice of Marcel contributed to the creation of images Duchamp, Man Ray left New York from photographic developments in July 1921 and moved to Paris. in the media during the 1930s. As a photographer, he played an The exhibition highlights the way Man active part in the Dadaist movement. Ray’s commercial work and artistic The fashion designer, Paul Poiret, projects continuously and mutually encouraged him to become a fashion enriched one another. The fashion photographer for magazines (Vogue, magazines, which lie at the root of the Femina, Vanity Fair) and illustrated creation of these images, engaged magazines (VU). He would go on with the photographs and in so doing to collaborate regularly with the their role in the popularisation of a American magazine, Harper’s Bazaar. new aesthetic was emphasised. Although his fashion photography At the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, was the result of intense hard work de la Faïence et de la Mode – and formed a large part of his career, Château Borély, the exhibition it is still relatively unknown today. continues with La Mode au Man Ray gave fashion photography a temps de Man Ray (Fashion in new lease of life through his technical the time of Man Ray), allowing inventiveness and an unprecedented us to place these photographs freedom with tone, -

Chefs-D'œuvre ? / Histoire D'ismes

EXPOSITION « CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE ? » CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE ? / HISTOIRE D’ISMES 2 — CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE I DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE I HISTOIRE D’ISMES SOMMAIRE 1. TABLEAU SYNOPTIQUE DES ŒUVRES 2. MOUVEMENTS ARTISTIQUES 2.1 LE FAUVISME Georges Braque, L’Estaque, 1906 2.2 LE CUBISME Pablo Picasso, La Bouteille de vieux marc, 1913 2.3 LE FUTURISME Gino Severini, La Danse du pan-pan au « Monico », 1959-1960 2.4 L’ORPHISME Sonia Delaunay et Guillaume Apollinaire, La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France, 1913 2.5 LE DADAÏSME Giorgio De Chirico, Portrait prémonitoire de Guillaume Apollinaire, 1914 2.6 LE SURREALISME Magritte, Le Modèle rouge, 1935 3. REGARDS CROISES EN HISTOIRE DES ARTS / ŒUVRES SURREALISTES 3.1 MAGRITTE, LE MODELE ROUGE, 1935 3.2 MAN RAY, LA FEMME 100 TETES, 1929 3.3 MAX ERNST, CHIMERE, 1928 3.4 MAN RAY, NOIRE ET BLANCHE, 1926 3 — CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE I DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE I HISTOIRE D’ISMES 1. TABLEAU SYNOPTIQUE DES ŒUVRES Ce tableau présente les œuvres de l’exposition qui peuvent être rattachées à ces courants artistiques, bien qu’elles ne soient pas toutes exploitées dans le dossier. De même, l’exposition évoluant au fil du temps, certaines œuvres sont susceptibles, au moment de la visite, d'avoir été décrochées ; il convient donc de vérifier avant la visite la présence effective de ces œuvres. Grande Nef Galerie 1 Galerie 2 Galerie 3 – Georges FAUVISME Braque, L’Estaque, 1906 – André Derain, Les Deux Péniches [1906] – André Derain, La Chute de Phaéton, char du soleil [1905-1906] – Juan Gris, La – Georges CUBISME Guitare, 1917 Braque, -

Man Ray: Works from a Private Collection Shepherd & Derom Galleries Spring 2009

MAN RAY: WORKS FROM A PRIVATE COLLECTION SHEPHERD & DEROM GALLERIES SPRING 2009 MAN RAY: WORKS FROM A PRIVATE COLLECTION April 28th through June 27th, 2009 Exhibition organized by Robert Kashey and David Wojciechowski Catalog by Leanne M. Zalewski with the assistance of Gilles Marquenie and Edouard Derom SHEPHERD & DEROM GALLERIES 58 East 79th Street New York, N.Y. 10075 Tel: 212 861 4050 Fax: 212 772 1314 [email protected] www.shepherdgallery.com © Copyright: Robert J. F. Kashey for Shepherd Gallery, Associates, 2009 COVER ILLUSTRATION: Kiki de Montparnasse [Alice Prin] with Baoule Mask, 1926, catalog no. 3. TECHNICAL NOTES: All measurements are in inches and in centimeters; height precedes width. All drawings, prints, and photographs are framed. Prices on request. All works subject to prior sale. SHEPHERD GALLERY SERVICES has framed, matted, and restored all of the objects in this exhibition, if required. The Service Department is open to the public by appointment, Tuesday through Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Tel: (212) 744 3392; fax (212) 744 1525; e-mail: [email protected]. MAN RAY: WORKS FROM A PRIVATE COLLECTION April 28 th – June 27 th , 2009 Shepherd & Derom Galleries are pleased to present works by Man Ray (1890-1976) from a private collection. Drawings, lithographs, and photographs in this exhibition range from an early design for chess pieces, dated 1920, to lithographs from the 1970s, as well as over fifty personal photographs of family and friends. Elsa Combe Martin, a close friend of the artist and his wife, received these works over a period of nearly fifty years. -

Dada, Surrealism, and Early Sound Cinema 2017

Marvellous Noise and Modest Recording Instruments: Dada, Surrealism, and Early Sound Cinema A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 Suzanne Mangion School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abstract p. 3 Declaration p. 4 Copyright Statement p. 5 Acknowledgements p. 6 Introduction p. 8 1. Concepts and Contexts of Dada/Surrealism-related Audio-Visuality p. 23 2. Readymade Soundtracks p. 65 3. Cut and Paste Cinema p. 110 4. Spoken Words, Silent Mouths p. 156 Concluding Notes and Future Directions p. 193 Bibliography p. 199 Filmography p. 226 word count 74, 991 2 Abstract This thesis assesses the ways in which films related to Dada and Surrealism used sound techniques during the 1920s and 1930s. It argues that their audio-visual approaches were distinctive, and related to important concepts and strategies within the movements such as collage, juxtaposition, and the Surrealist ‘marvellous.’ Historical research is combined with close analysis and theoretical interpretation to examine the early sound film context in detail, while also bringing a new aural perspective to Dada and Surrealist cinema studies. The project addresses an important, yet neglected, part of film sound history, while also pushing art historical interpretation of these works beyond a long-held visual bias. Dada and Surrealist cinema's heyday coincided with the period of transition from silent to sound film, and several filmmakers associated with these movements, including Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, Jean Cocteau, and Hans Richter, were at the forefront of this change, producing some of the earliest sound films in their countries of work. -

Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

240 wendy a. grossman 100 Man Ray, Noire et blanche, 1926. Auction result on Art Market Monitor, 2017. 241 Surrealism and the Marketing of Man Ray’s Photographs in America: The Medium, the Message, and the Tastemakers Wendy A. Grossman On November 9, 2017, a print of Man Ray’s Noire et blanche set a remark- able $3,125,483.66 record at Christie’s auction in Paris, selling for nearly twice its high estimate (fig. 100). It was not only a record for the artist’s work in the photographic medium but also for the sale at auction of any vintage photograph. Even as the provenance of this record-breaking photographic print inevitably contributed to establishing its extraordi- nary value at market—it was initially owned by the preeminent Parisian fashion designer and estimable collector Jacques Doucet—various prints of this work have continued to climb to the top of photography auction sales over the course of the past several decades, indicating a definite trend.1 The secure place of Noire et blanche in the pantheon of twentieth-cen- tury photography long predated this record-breaking sale. Featured in the 2005 publication Photo Icons: The Story Behind the Pictures, the work was classified as “one of the most sought-after treasures in the interna- tional photographic trade.”2 With a dozen or so known authenticated vintage prints of this iconic composition in both institutional and pri- 1 I want to express my appreciation to Francis Naumann and Edouard Sebline for their valuable input and encouragement throughout the development of this essay. -

Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens

exhibition preview Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens Wendy Grossman and Letty Bonnell he exhibition “Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens” explores a little-examined facet in the development of Modernist artistic prac- tice; namely, the instrumental role photographs played in the process by which African objects— formerly considered ethnographic curiosi- ties—came to be perceived as the stuff of Modern art in the first Tdecades of the twentieth century. At the center of this project are MAN RAY, AFRICAN ART, AND THE MODERNIST LENS both well-known and recently discovered photographs by the American artist Man Ray (1890–1976), whose body of images OCTOBER 10, 2009–JanuaRY 10, 2010 translating the vogue for African art into a Modernist photo- THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION, WASHINGTON DC graphic aesthetic made a significant impact on shaping percep- tions of such objects at a critical moment in their reception. August 7–OCTOBER 10, 2010 Man Ray was first introduced to the art of Africa in a semi- THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA ART MUSEUM, nal exhibition of African sculpture at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gal- CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA lery in 1914. While his 1926 photograph Noire et blanche (Fig. 1) would later become an icon of Modernist photography, a large OCTOBER 2010–JanuaRY 2011 body of his lesser-known work provides new insight into how UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA MUSEUM OF his photographs both captured and promoted the spirit of his ANTHROPOLOGY, VANCOUVER, CANADA age. From that initial discovery of the African aesthetic in New York to the innovative photographs he later made in Paris in the The associated catalogue by Wendy Grossman includes full 1920s and ‘30s, Man Ray’s images illustrate the way that African documentation of the photographs (many never previously art acquired new meanings in conjunction with photography published) and the African objects they feature, with a pref- becoming legitimized as a Modernist art form. -

Read a Free Sample

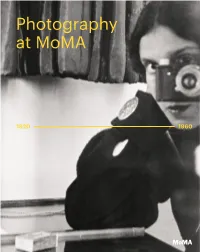

Photography at MoMA Contributors Quentin Bajac is The Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Museum of Modern Art draws upon the exceptional depth of its collection to tell a new history of photography in the three-volume series Photography at MoMA. Douglas Coupland is a Vancouver-based artist, writer, and cultural critic. The works in Photography at MoMA: 1920–1960 chart the explosive development Lucy Gallun is Assistant Curator in the Department of the medium during the height of the modernist period, as photography evolved of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, from a tool of documentation and identification into one of tremendous variety. New York. The result was nothing less than a transformed rapport with the visible world: Roxana Marcoci is Senior Curator in the Department Walker Evans's documentary style and Dora Maar's Surrealist exercises in chance; of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, El Lissitzky's photomontages and August Sander's unflinching objectivity; New York. the iconic news images published in the New York Times and Man Ray's darkroom experiments; Tina Modotti's socioartistic approach and anonymous snapshots Sarah Hermanson Meister is Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum taken by amateur photographers all over the world. In eight chapters arranged of Modern Art, New York. by theme, this book presents more than two hundred artists, including Berenice Abbott, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Geraldo de Barros, Margaret Bourke-White, Kevin Moore is an independent curator, writer, Bill Brandt, Claude Cahun, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, and advisor in New York. -

Man Ray Et La Mode 23 Septembre 2020 - 17 Janvier 2021

MAN RAY ET LA MODE 23 SEPTEMBRE 2020 - 17 JANVIER 2021 DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE MAN RAY ET LA MODE 23 septembre 2020 - 17 janvier 2021 Sommaire 2 Présentation de l’exposition ....................3 Pistes pédagogiques .............................4 Biographie de Man Ray ...........................5 Les années Folles .................................7 Le portrait mondain ..............................8 La mode des années 1920 ........................9 Focus : Coco Chanel .............................10 La mode des années 1930 ........................11 Les revues ........................................12 La publicité/ la cosmétique .....................13 Man Ray, Dada et le surréalisme ...............14 Focus : analyse de Noire et blanche ...........15 Les techniques photographiques lexique .....16 Bibliographie ..................................... 17 en couverture Man Ray, Personne non identifiée, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Adagp, Paris 2019 MAN RAY ET LA MODE 23 septembre 2020 - 17 janvier 2021 L’exposition 3 Le travail de Man Ray comme photographe de mode n’est pas la partie la plus connue de son œuvre et n’avait jamais fait l’objet d’une exposition spécifique. Avec sa participation aux revues les plus importantes de son temps comme Vanity Fair, Vogue et Harper’s Bazaar, Man Ray a pourtant contribué à définir le genre de la photographie de mode. Pendant les années 1920 et 1930, il a su magnifier les créations de Paul Poiret, de Gabrielle Chanel ou encore d’Elsa Schiaparelli en les traitant comme des œuvres d’art, dans une vision largement influencée par le surréalisme. L’exposition comporte 4 grandes sections : ● À l’entrée de l’exposition, l’Introduction permet de situer la pratique de Man Ray photographe de mode dans le parcours de l’artiste. -

Man Ray Et Retracer Le Processus De Création Dans L'élaboration De Son Oeuvre

A travers les quelque 500 oeuvres rassemblées exceptionnellement pour cette exposition, on pourra suivre le parcours du photographe Man Ray et retracer le processus de création dans l'élaboration de son oeuvre . L'exposition s'articulera autour de trois axes principaux MAN visant à illustrer de façon générale le problème de la représentation. La première partie montrera aussi bien les photographies de mode que les paysages et les très nombreux contacts de portraits RAY découverts grâce à la dation faite au Centre la photographie à l'envers Georges Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne en 1994. Galeries nationales La deuxième partie de l'exposition cherchera du Grand Palais à mettre en valeur les oeuvres majeures de 29 avril-29 juin 1998 l'artiste, provenant des plus grandes collections internationales publiques et privées, ainsi que des documents originaux, pour la plupart inédits, issus de la collection du Centre Dans le cadre de sa programmation Georges Pompidou, Musée national d'art Hors Les Murs, le Centre Georges Pompidou, moderne, résultant de son travail personnel Musée national d'art moderne, présente, et des techniques complexes qu'il a utilisées ou du 29 avril au 29 juin 1998, dans les Galeries mises au point (solarisation, surimpression, nationales du Grand Palais, une importante trame, rayogramme) et qui visaient toutes exposition monographique consacrée à masquer ou déguiser "l'effet de réel". à l'ensemble du travail photographique de Man Ray (1890-1976). Une troisième partie viendra conclure ce parcours à travers la pratique photographique L'exposition "Man Ray, la photographie et créative de Man Ray en mettant l'accent à l'envers " conçue et réalisée par le Centre sur toutes les oeuvres situées entre les deux Georges Pompidou, Musée national d'art pôles stylistiques et techniques bien distincts moderne est la première exposition basée de son activité.