Reform of Statistical Inference in Psychology: the Case Of<Emphasis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Committee

Welcome to SARMAC VIII this is that place kore ya kono of going away and coming back yuku mo kaeru mo of parting time and again wakarete wa both friends and strangers shiru mo shiranu mo the Ausaka Barrier Ausaka no Seki Semimaru, 9th century, Hyakunin Isshu (“One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each”) Welcome to Kyoto, and to the 8th SARMAC meeting. In this ancient city dotted with temples, shrines and gardens, we showcase the best of contemporary applied research in memory and cognition. It's a wide and varied program, sure to intrigue you. To those of you who have never joined us before, SARMAC is known for its friendliness: we don't have an "inner circle" here. To our long-time SARMACsters, welcome back. And to those of you who haven't been back for a while, welcome home. Maryanne Garry President, Governing Board Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition SARMAC Japan Program Committee Kazuo Mori, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Chair Amy Bradfield Douglass, Bates College Maryanne Garry, Victoria University of Wellington Harlene Hayne, University of Otago Emily Holmes, University of Oxford Christian Meissner, University of Texas at El Paso Makiko Naka, Hokkaido University Aldert Vrij, University of Portsmouth SARMAC Japan Organizing Committee Yukio Itsukushima, Nihon University, Chair Jun Kawaguchi, Nagoya University, Vice-Chair Yuji Itoh, Keio University, Secretary General Kazuo Mori, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Makiko Naka, Hokkaido University Masanobu Takahashi, University of Sacred Heart Yuji -

People V. Lerma, 2014 IL App (1St) 121880

Illinois Official Reports Appellate Court People v. Lerma, 2014 IL App (1st) 121880 Appellate Court THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Caption EDUARDO LERMA, Defendant-Appellant. District & No. First District, First Division Docket No. 1-12-1880 Filed September 8, 2014 Rehearing denied October 8, 2014 Held Defendant’s convictions for first degree murder, personally (Note: This syllabus discharging a firearm that caused death, and aggravated discharge of a constitutes no part of the weapon in connection with a murder were reversed and the cause was opinion of the court but remanded for a new trial on the ground that the trial court committed has been prepared by the reversible error by denying defendant’s motion to present expert Reporter of Decisions testimony on the misconceptions commonly involved in evaluating for the convenience of identification testimony, since the record showed that the trial court the reader.) failed to give proper consideration to the proffered testimony, especially when defendant alleged that his convictions stemmed from factors underlying these misconceptions, and the trial court was directed to allow the expert testimony subject to Rule 702 of the Illinois Rules of Evidence. Decision Under Appeal from the Circuit Court of Cook County, No. 08-CR-9899; the Review Hon. Timothy J. Joyce, Judge, presiding. Judgment Reversed and remanded with directions. Counsel on Michael J. Pelletier, Alan D. Goldberg, and Linda Olthoff, all of State Appeal Appellate Defender’s Office, of Chicago, for appellant. Anita M. Alvarez, State’s Attorney, of Chicago (Alan J. Spellberg and Janet C. Mahoney, Assistant State’s Attorneys, of counsel), for the People. -

Wednesday, July 2Nd

abstracts SARMAC V ABSTRACTS Aberdeen, Scotland July 2-6 2003 Co-Chairs: Lauren R. Shapiro, Amina Memon, Fiona Gabbert, Rhiannon Ellis WEDNESDAY, JULY 2ND REGISTRATION 2:00 - 5:00 p.m. Auditorium SYMPOSIA 3:15 - 5:15 p.m. Cognitive aspects of anxiety and depression Chair: PAULA HERTEL Contact: [email protected] Keywords: Cognitive function, Emotion The symposium includes reports of recent research on a variety of topics related to cognition in emotionally disordered states: the interpretation of facial expression, the interpretation and recall of verbal material, autobiographical memory, and the generation of mental models. Selective processing of threatening facial expressions: The eyes have it! Elaine Fox Previous work suggests that threatening facial expressions are detected more efficiently than happy facial expressions in a visual search task. It is not clear, however, which component of the face indicates threat. Is it a conjunction of features that might indicate threat (e.g., a frown in conjunction with a downward turned mouth), or could the eye or mouth region alone indicate threat efficiently? The present study tested which features of the face produced a threat-superiority effect and whether the level of self-reported trait-anxiety further enhanced this effect. Participants were divided into high and low-anxious groups on the basis of their scores on standardized measures of trait (and state) anxiety. Across several experiments, it was found that the eye-region did produce a threat-superiority effect with upright faces but not with inverted faces, while the mouth region did not. However, high levels of trait-anxiety failed to influence the magnitude of this threat-superiority effect. -

Memory and Ministry: Young Adult Nostalgia, Immigrant Amnesia

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 2010 Memory and Ministry: Young Adult Nostalgia, Immigrant Amnesia Brett C. Hoover Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Hoover, Brett C. “Memory and Ministry: Young Adult Nostalgia, Immigrant Amnesia,” New Theology Review 23, no. 1 (February 2010): 58-67. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. new theology review • february 2010 Memory and Ministry Young Adult Nostalgia, Immigrant Amnesia Brett C. Hoover, C.S.P. A problem with memory occurs in two ways that directly affect pastoral issues: when we reconstruct our history as a community of faith in a way that romanticizes the past and anathematizes the present (nostalgia) or when we reconstruct the past eliminating crucial information we would rather ignore (amnesia), particular for ministry to and with the young and immigrants. Drawing on J. B. Metz’s approach to Christian memory, ministers can engage the dangerous memory in a way that coincides with the needs of young people and our nation’s newest residents. church of tradition is by definition a church of memory. Yet memory is a A precarious thing. As Christians, we remember what the God of Jesus Christ has done for us, and this powerfully impacts how we worship and minister to one another. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:13-cv-00221 Document #: 204 Filed: 08/18/16 Page 1 of 22 PageID #:<pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION RODELL SANDERS, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Case No. 13 C 0221 v. ) ) CITY OF CHICAGO HEIGHTS, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER AMY J. ST. EVE, District Court Judge: On July 8, 2016, Defendant City of Chicago Heights, Illinois (“Chicago Heights” or the “City”) and individual Defendant Chicago Heights Police Officers Jeffrey Bohlen and Robert Pinnow moved to exclude the expert testimony of Plaintiff Rodell Sanders’ police practices expert Dr. William T. Gaut and Plaintiff’s eyewitness identification expert Dr. Geoffrey Loftus pursuant to the Federal Rules of Evidence and Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharms., Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 113 S. Ct. 2786, 125 L. Ed. 2d 469 (1993). This is Defendants’ second Daubert motion concerning Dr. Gaut, and the Court presumes familiarity with its May 2, 2016 Memorandum Opinion and Order granting in part and denying in part the first Daubert motion. Also, the Court presumes familiarity with its May 17, 2016 Memorandum Opinion and Order granting in part and denying in part Defendants’ summary judgment motions.1 For the following reasons, the Court, in its discretion, denies the present Daubert motion because Sanders has met his burden 1 The Court’s earlier rulings control the present Daubert motion under the law of the case doctrine. See Kathrein v. City of Evanston, Ill., 752 F.3d 680, 685 (7th Cir. 2014) (a “ruling made in an earlier phase of a litigation controls the later phases unless a good reason is shown to depart from it.”). -

Unspringing the Witness Memory and Demeanor Trap: What Every Judge and Juror Needs to Know About Cognitive Psychology and Witness Credibility

Unspringing The Witness Memory and Demeanor Trap: What Every Judge And Juror Needs to Know About Cognitive Psychology And Witness Credibility By: Mark W. Bennett Unspringing The Witness Memory and Demeanor Trap: What Every Judge And Juror Needs to Know About Cognitive Psychology And Witness Credibility 1 Mark W. Bennett The soul of America’s civil and criminal justice systems is the ability of jurors and judges to accurately determine the facts of a dispute. This invariably implicates the credibility of witnesses. In making credibility determinations, jurors and judges necessarily decide the accuracy of witnesses’ memories and the effect of the witnesses’ demeanor on their credibility. Almost all jurisdictions’ pattern jury instructions about witness credibility explain nothing about how a witness’s memories for events and conversations work—and how startlingly fallible memories actually are. They simply instruct the jurors to consider the witness’s “memory”—with no additional guidance. Similarly, the same pattern jury instructions on demeanor seldom do more than ask jurors to speculate about a witness’s demeanor by instructing them to merely observe “the manner of the witness” while testifying. Yet, thousands of cognitive psychological studies have provided major insights into witness memory and demeanor. The resulting cognitive psychological principles that are now widely accepted as the gold standard about witness memory and demeanor are often contrary to what jurors intuitively, but wrongly, believe. Most jurors believe that memory works like a video camera that can perfectly recall the details of past events. Rather, memory is more like a Wikipedia page where you can go in and change it, but so can others. -

The Reality of Repressed Memories

American Psychologist © 1993 by the American Psychological Association May 1993 Vol. 48, No. 5, 518-537 For personal use only--not for distribution. The Reality of Repressed Memories Elizabeth F. Loftus Department of Psychology University of Washington ABSTRACT Repression is one of the most haunting concepts in psychology. Something shocking happens, and the mind pushes it into some inaccessible corner of the unconscious. Later, the memory may emerge into consciousness. Repression is one of the foundation stones on which the structure of psychoanalysis rests. Recently there has been a rise in reported memories of childhood sexual abuse that were allegedly repressed for many years. With recent changes in legislation, people with recently unearthed memories are suing alleged perpetrators for events that happened 20, 30, even 40 or more years earlier. These new developments give rise to a number of questions: (a) How common is it for memories of child abuse to be repressed? (b) How are jurors and judges likely to react to these repressed memory claims? (c) When the memories surface, what are they like? and (d) How authentic are the memories? This article is an expanded version of an invited address, the Psi Chi/Frederick Howell Lewis Distinguished Lecture, presented at the 100th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington DC, August 1992. I thank Geoffrey Loftus, Ilene Bernstein, Lucy Berliner, Robert Koscielny, and Richard Ofshe for very helpful comments on earlier drafts. I thank many others, especially Ellen Bass, Mark Demos, Judie Alpert, Marsha Linehan, and Denise Park for illuminating discussion of the issues. My gratitude for the vast efforts of the members of the Repressed Memory Research Group at the University of Washington is beyond measure. -

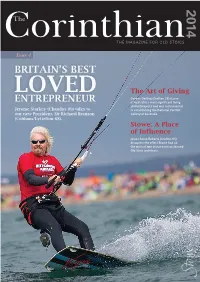

The Corinthian 2014

Old Stoic Society Committee President: Sir Richard Branson (Cobham/Lyttelton 68) Vice President: THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Dr Anthony Wallersteiner (Headmaster) Chairman: Simon Shneerson (Temple 72) Issue 4 Vice Chairman: Patrick Cooper (Chatham 86) Director: Anna Semler (Nugent 05) Members: John Arkwright (Cobham 69) Peter Comber (Grenville 70) The Art of Giving Colin Dudgeon (Hon. Member) Gordon Darling (Grafton 39) is one Hannah Durden (Nugent 01) of Australia’s most significant living John Fingleton (Chatham 66) philanthropists and was instrumental Ivo Forde (Walpole 67) Jerome Starkey (Chandos 99) talks to in establishing the National Portrait Jonathon Hall (Bruce 79) our new President, Sir Richard Branson Gallery of Australia. Tim Hart (Chandos 92) (Cobham/Lyttelton 68). Katie Lamb (Lyttelton 06) Stowe: A Place Nigel Milne (Chandos 68) Ben Scholfield (Temple 99) of Influence Jules Walker (Lyttelton 82) James Furse-Roberts (Grafton 95) discovers the effect Stowe had on the work of two of our most acclaimed Old Stoic architects. Old Stoic Society Stowe School Stowe Buckingham MK18 5EH United Kingdom Telephone: +44 (0) 1280 818349 Email: [email protected] www.oldstoic.co.uk www.facebook.com/OldStoicSociety ISSN 2052-5494 Design and production: MCC Design, mccdesign.com THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Issue 4 FEATURES 6 BRitain’S Best Loved 16 THE ART OF GIVING ENTREPRENEUR Gordon Darling (Grafton 39) is one Jerome Starkey (Chandos 99) talks of Australia’s most significant living to our new President, Sir Richard philanthropists and was instrumental Branson (Cobham/Lyttelton 68). in establishing the National Portrait Gallery of Australia. 12 OLYMPIC FLOWER TURF AT THE 18 STOWE: A PLACE OF INFLUENCE OLYMPIC OPENING CEREMONY James Furse-Roberts (Grafton 95) David Hewetson-Brown (Chatham 56) explains the history behind his farm discovers the effect Stowe had on the Tuesday 10 June 2014 and how he diversified to produce work of two of our most acclaimed 7.00pm – 12.30am wild flower turf for the Olympics. -

CONDENSED SCHEDULE Thursday Morning Vision I (1-15) ..., ...8:30

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 241 1977, Vol. 10 (4),241-282 CONDENSED SCHEDULE Thursday Morning Vision I (1-15) ... .. .. ..... ... , .. .. ... ... ... ...... ...... 8:30-12:35, Empire Room Information Processing 1(16-33) ... .. .... .. ...... .. ... .. .. 8:30-12:45, Palladian Room Attention and Vigilance (34-41) .. .. ; .... ... ... .... .. ..... .... .. 8:30-10:35, Club Room A Performance and Reaction Time (42-48) ... .. .. ..... .... .. ... ... 10:50-12:25, Club Room A Psychopharmacology (49-63) ...... .... ... ..... , ...... ..... .. .. 8:30-12:15, Forum Room Animal Conditioning (64-78) .. ; . ... ... .. .. .. .. ...... 8:30-12:30, Diplomat Room Avoidance Learning (79-88) .... ... ................... .. .. .. .... 8:30-11: 15 , Tudor Room Thursday Afternoon Perception I (89-107) . ...... .. ........ .. ... ... .. .. ... ..... 1:00-5:05, Empire Room Information Processing II (108-128) .. ... ... ..... ........ ... ..... 1:00-5:35, Palladian Room Social-Personality Processes (I 29-142b) .. .. ... ........ .. .. .. 1: 00-4:40, Club Room A Physiological (143-154) .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .. .. ... ... 1: 15-3:55, Forum Room Animal Motivation (155-163) . .. .. ........ ....... .. .. .. ... .. ... 1:00-3 :20, Tudor Room Brain Function I (164-170) .. .... ...... ... .. .. ... .. .. ... .. ... ... ... 3:55-5 :10, Tudor Room Memory and Recall I (l71-185b) .. .. .. .. .. .... ..... .......... 1:00 -5 :05, Diplomat Room Friday Morning Memory and Recall II (186-199) . .. .. ... ... .... .. .. .... .. ...... 8:30-12:30, Empire -

Consciousness, Accessibility, and the Mesh Between Psychology

Forthcoming in Behavioral and Brain Sciences Consciousness, Accessibility, and the Mesh between Psychology and Neuroscience Ned Block New York University Abstract How can we disentangle the neural basis of phenomenal consciousness from the neural machinery of the cognitive access that underlies reports of phenomenal consciousness? We can see the problem in stark form if we ask how we could tell whether representations inside a Fodorian module are phenomenally conscious. The methodology would seem straightforward: find the neural natural kinds that are the basis of phenomenal consciousness in clear cases when subjects are completely confident and we have no reason to doubt their authority, and look to see whether those neural natural kinds exist within Fodorian modules. But a puzzle arises: do we include the machinery underlying reportability within the neural natural kinds of the clear cases? If the answer is ‘Yes’, then there can be no phenomenally conscious representations in Fodorian modules. But how can we know if the answer is ‘Yes’? The suggested methodology requires an answer to the question it was supposed to answer! The paper argues for an abstract solution to the problem and exhibits a source of empirical data that is relevant, data that show that in a certain sense phenomenal consciousness overflows cognitive accessibility. I argue that we can find a neural realizer of this overflow if assume that the neural basis of phenomenal consciousness does not include the neural basis of cognitive accessibility and that this assumption is justified (other things being equal) by the explanations it allows. Introduction In The Modularity of Mind, Jerry Fodor argued that significant early portions of our perceptual systems are modular in a number of respects, including that we do not have cognitive access to their internal states and representations of a sort that would allow reportability (Fodor, 1983; see also Pylylshyn, 2003; Sperber, 2001). -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Blended Memory: Distributed Remembering and Forgetting through Digital Photography Tim Fawns PhD Education The University of Edinburgh 2016 ii Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed by me and that it is my own work. The work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Publications derived from this research have been included at the end with the publishers’ permission. These publications are my own work, except where indicated. Signed: Tim Fawns iii iv Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Hamish Macleod and Ethel Quayle, thank you for creating an atmosphere of enjoyment, creativity, trust and curiosity, as well as for tolerating and guiding my many directions and slowly evolving understanding. To Fiona Hale, thank you for your generous moral and practical support. -

Geoffrey Loftus Outlines Many Important Misconceptions Relative To

Declaration of Geoffrey R. Loftus, Ph.D in the case of Javier Suarez Medina I. Qualifications My name is Geoffrey R. Loftus. I am a Professor of Psychology at the University of Washington in Seattle. My area of expertise, in which I have been working for 30 years, is human perception and memory. Over the past ten years, I have qualified as an expert in perception and memory in approximately 120 criminal cases in nine states, federal courts in six cities, and U.S. Military court in Sigonella, Italy. My curriculum vitae is attached. II. Information Relied Upon I am familiar with the following facts and circumstances surrounding the accusation that Javier Suarez Medina shot Michael Mesley, as described in the police reports and testimony at Mr. Medina’s trial. As I understand it, Michael Mesley came forward after seeing television coverage of Javier Suarez Medina’s murder trial in 1989. Mr. Mesley testified that he recognized Javier Suarez Medina as one of three people who assaulted him and his wife nearly two years earlier on October 10, 1987. According to Mr. Mesley, he and his wife were in seated in their Mazda truck parked on a hill near a residential area in Dallas to watch the State Fair fireworks. At some time between 8:40 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. two men approached the driver side of the truck, where Mesley was seated, and one man approached the passenger side of the truck, where his wife was seated. Mesley testified that a “Latin” man stuck a 12-gauge shotgun in his face and said “give me your money or I’m going to blow your f---in’ head off.” The man then took Mesley’s money, his wife’s purse, his camera equipment and told him to walk toward the woods.