ONLINE CHAPTER 2 CHROMATIC CHORDS FUNCTIONING AS the PREDOMINANT Artist in Residence: Jacqueline Du Pré

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: an Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: An Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara BM, University of Southern Mississippi, 2001 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2003 Committee Chair: Lee Fiser, BM Abstract This document on cello pedagogy and playing focuses on the importance of the kinesthetic sense as it relates to teaching and performance quality. William Conable, creator of body mapping, has described how the kinesthetic sense or movement sense provides information about the body’s position and size, and whether the body is moving and, if so, where and how. In addition Craig Williamson, pioneer of Somatic Integration, claims that the kinesthetic sense enables one to sense what the body is doing at any time, including muscular effort, tension, relaxation, balance, spatial orientation, distance, and proportion. Cellists can develop and awaken the kinesthetic sense in order to have conscious body awareness, and to understand that cello playing is a physical, aerobic, intellectual, and musical activity. This document describes the physical, motion, aerobic, anatomic, and kinesthetic approach to cello playing and is supported by somatic education methods, such as the Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method, and Yoga. By applying body awareness and kinesthesia in cello playing, cellists can have freedom, balance, ease in their movements, and an intelligent way of playing and performing. ii Copyright © 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg

Ryan Weber: Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg Grieg‘s intriguing statement, ―the realm of harmonies has always been my dream world,‖1 suggests the rather imaginative disposition that he held toward the roles of harmonic function within a diatonic pitch space. A great degree of his chromatic language is manifested in subtle interactions between different pitch spaces along the dualistic lines to which he referred in his personal commentary. Indeed, Grieg‘s distinctive style reaches beyond common-practice tonality in ways other than modality. Although his music uses a variety of common nineteenth- century harmonic devices, his synthesis of modal elements within a diatonic or chromatic framework often leans toward an aesthetic of Impressionism. This multifarious language is most clearly evident in the composer‘s abundant songs that span his entire career. Setting texts by a host of different poets, Grieg develops an approach to chromaticism that reflects the Romantic themes of death and despair. There are two techniques that serve to characterize aspects of his multi-faceted harmonic language. The first, what I designate ―chromatic juxtapositioning,‖ entails the insertion of highly chromatic material within ^ a principally diatonic passage. The second technique involves the use of b7 (bVII) as a particular type of harmonic juxtapositioning, for the flatted-seventh scale-degree serves as a congruent agent among the realms of diatonicism, chromaticism, and modality while also serving as a marker of death and despair. Through these techniques, Grieg creates a style that elevates the works of geographically linked poets by capitalizing on the Romantic/nationalistic themes. -

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Eduqas-Bach-Badinerie-Musical-Analysis.Pdf

Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie J.S.Bach: BADINERIE from Orchestral Suite No.2 Melodic Analysis The entire movement is based on two musical motifs: X and Y. Section A Bars 02 – 161 Sixteen bars Bars 02 – 21 The movement opens with the first statement of motif X, which is played by the flute. The motif is a descending B minor arpeggio/broken chord with a characteristic quaver and semiquaver(s) rhythm. Bars 22 – 41 The melodic material remains with the flute for the first statement of motif Y. This motifis an ascending semiquaver figure consisting of both arpeggios/broken chords sand conjunct movement. Bars 42 – 61 Motif X is then restated by the flute. Music | Bach: Badinerie - Musical Analysis 1 Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie Bars 62 – 81 Motif X is presented by the cellos in a slightly modified version in which the last crotchet of the motif is replaced with a quaver and two semiquavers. This motif moves the tonality to A major and is also the initial phrase in a musical sequence. Bars 82 – 101 Motif X remains with the cellos with a further modified ending in which the last crotchet is replaced with four semiquavers. It moves the tonality to the dominant minor, F# minor, and is the answering phrase in a musical sequence that began in bar 62. Bars 102 – 121 Motif Y returns in the flute part with a modified ending in which the last two quavers are replaced by four semiquavers. Bars 122 – 161 The flute continues to present the main melodic material. Motif Y is both extended and developed, and Section A is brought to a close in F# minor. -

Andrzej Bauer

Andrzej Bauer Winner of the first prize at the ARD International Competition in Munich, prizewinner at the Prague Spring International Competition and recipient of the prize awarded under the auspices of the European Parliament and the Council of Europe. Andrzej Bauer was born in Łódź, where he completed his studies under Kazimierz Michalik’s guidance. He continued his musical education, working with e.g. André Navarra, Miloš Sadlo and Daniel Szafran during numerous masterclasses. He also completed a two-year course in London, under William Pleeth, thanks to a scholarship funded by Witold Lutosławski. Andrzej Bauer has given recitals in Amsterdam, Paris, Hamburg and Munich, and performed with symphony orchestras, including the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, RAI Naples Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra and Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. He has appeared in concert as a soloist with most Polish symphony and chamber orchestras, with ensembles like the National Philharmonic Orchestra and Sinfonia Varsovia inviting him to join them as a soloist on their European concert tours. Andrzej Bauer has recorded music for a number radio and television stations in Poland and other countries. He has taken part in international festivals, performing in most European countries as well as the United States and Japan. The artist’s recording with works by Schubert, Brahms and Schumann (Koch/Schwann) won the quarterly German Record Critics’ Award. His subsequent CDs featured works by Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Messiaen, Panufnik as well as Witold Lutosławski’s Cello Concerto. 2000 saw the release of the first ever Polish recording (on two CDs) of all of Bach’s cello suites, recorded by Bauer for the CD Accord label, for which the artist won the 2000 Fryderyk Award of the Polish Academy of Phonography. -

Day 17 AP Music Handout, Scale Degress.Mus

Scale Degrees, Chord Quality, & Roman Numeral Analysis There are a total of seven scale degrees in both major and minor scales. Each of these degrees has a name which you are required to memorize tonight. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 & w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic A triad can be built upon each scale degree. w w w w & w w w w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic The quality and scale degree of the triads is shown by Roman numerals. Captial numerals are used to indicate major triads with lowercase numerals used to show minor triads. Diminished triads are lowercase with a "degree" ( °) symbol following and augmented triads are capital followed by a "plus" ( +) symbol. Roman numerals written for a major key look as follows: w w w w & w w w w w w w w CM: wI (M) iiw (m) wiii (m) IV (M) V (M) vi (m) vii° (dim) I (M) EVERY MAJOR KEY FOLLOWS THE PATTERN ABOVE FOR ITS ROMAN NUMERALS! Because the seventh scale degree in a natural minor scale is a whole step below tonic instead of a half step, the name is changed to subtonic, rather than leading tone. Leading tone ALWAYS indicates a half step below tonic. Notice the change in the qualities and therefore Roman numerals when in the natural minor scale. -

Kostka, Stefan

TEN Classical Serialism INTRODUCTION When Schoenberg composed the first twelve-tone piece in the summer of 192 1, I the "Pre- lude" to what would eventually become his Suite, Op. 25 (1923), he carried to a conclusion the developments in chromaticism that had begun many decades earlier. The assault of chromaticism on the tonal system had led to the nonsystem of free atonality, and now Schoenberg had developed a "method [he insisted it was not a "system"] of composing with twelve tones that are related only with one another." Free atonality achieved some of its effect through the use of aggregates, as we have seen, and many atonal composers seemed to have been convinced that atonality could best be achieved through some sort of regular recycling of the twelve pitch class- es. But it was Schoenberg who came up with the idea of arranging the twelve pitch classes into a particular series, or row, th at would remain essentially constant through- out a composition. Various twelve-tone melodies that predate 1921 are often cited as precursors of Schoenberg's tone row, a famous example being the fugue theme from Richard Strauss's Thus Spake Zararhustra (1895). A less famous example, but one closer than Strauss's theme to Schoenberg'S method, is seen in Example IO-\. Notice that Ives holds off the last pitch class, C, for measures until its dramatic entrance in m. 68. Tn the music of Strauss and rves th e twelve-note theme is a curiosity, but in the mu sic of Schoenberg and his fo ll owers the twelve-note row is a basic shape that can be presented in four well-defined ways, thereby assuring a certain unity in the pitch domain of a composition. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

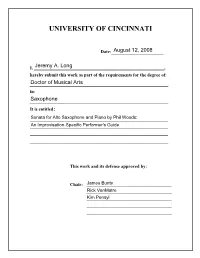

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods.