My Best Games of Chess 1905-1954

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 1950 EVERY SECOND MONTH T BIR.THDAY WEEK.END TOURNA^Rtents T SOUTHSEA TOURNEY T Overseos & N.Z

rTE ]IEW ZEALAII[I Vol. 3-No. 14 JUNE 1950 EVERY SECOND MONTH t BIR.THDAY WEEK.END TOURNA^rtENTS t SOUTHSEA TOURNEY t Overseos & N.Z. Gomes ,1 ts t PROBLEMS + TH E SLAV DEFENCE :-, - t lr-;ifliir -rr.]t l TWO SH ILLIN GS "Jl 3 OIIDSSPLAYBBSe LIBBABY 3 ,,C BOOKS BOOKS H E INTER SOLD BY Fol rvhich tir THE NEW ZEATAND CHESSPLAYER ANNUAL 256 DOMTNION ROAD, LIFI AUCKLAND. PHONE 64-277 (Ne In ordering, merely quote Editor and I catalogue number shown. Postage: Add one penny in every Z/- Champion anr Australia. GAMES G l3-Fifty Great Games of Modern Chess- Golombek. G l-My Best Well annotated. and very gc - _ What son' Games, 1924-32-Alekhine. 120 value. 4/3 games by the greatest player and the greatest annotator. 14/- G l4-Moscow - Prague Match, lg46-The -_ " I take games of exceptional interest Revierv.' Your G 2-Capablanca's Hundred Best Games- to all advanc._ Forest Hills. l p_lay_ery (not recommended beginners Golombek. A book grace for " I have lea, to everv- chess WeII indexed for openings ; and endings. 3/- ancl Purdy's r player's _ library. Well-selected games extensively G l5-Amenities and Background all the other l annotated. 17/G of Che=. bought."-H.A Play-Napier. Delightful liiile book of gre=. G 3-Tarrasch's Best Games-Reinfeld. 1BB " One maga fully annotated games based on Tarrasch,s g_a1es by a master of Chess and writing. 3/- -'eaches chess' own notes. 23/- G 16-Great Britain v. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

Dutchman Who Did Not Drink Beer. He Also Surprised My Wife Nina by Showing up with Flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital Just Before She Gave Birth to My Son Mitchell

168 The Bobby Fischer I Knew and Other Stories Dutchman who did not drink beer. He also surprised my wife Nina by showing up with flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital just before she gave birth to my son Mitchell. I hadn't said peep, but he had his quiet ways of finding out. Max was quiet in another way. He never discussed his heroism during the Nazi occupation. Yet not only did he write letters to Alekhine asking the latter to intercede on behalf of the Dutch martyrs, Dr. Gerard Oskam and Salo Landau, he also put his life or at least his liberty on the line for several others. I learned of one instance from Max's friend, Hans Kmoch, the famous in-house annotator at AI Horowitz's Chess Review. Hans was living at the time on Central Park West somewhere in the Eighties. His wife Trudy, a Jew, had constant nightmares about her interrogations and beatings in Holland by the Nazis. Hans had little money, and Trudy spent much of the day in bed screaming. Enter Nina. My wife was working in the New York City welfare system and managed to get them part-time assistance. Hans then confided in me about how Dr. E greased palms and used his in fluence to save Trudy's life by keeping her out of a concentration camp. But mind you, I heard this from Hans, not from Dr. E, who was always Max the mum about his good deeds. Mr. President In 1970, Max Euwe was elected president of FIDE, a position he held until 1978. -

La Comprensione Del Gioco

LLOOGGIICCAALL TTHHIINNKKIINNGG di Riccardo Annoni A.S.D. Circolo Scacchistico della Versilia Cari amici scacchisti, l’estate è agli sgoccioli e inizia a salirmi la febbre degli scacchi, dopo qualche mese di digiuno mi ritrovo a salivare per le 64 caselle. Per adesso mi sfogo su Word con questo articoletto [era iniziato così… ora ormai è un libello – n.d.a.] che apro trascrivendo qui sotto un passo del celebre libro “Think Like a Grandmaster” di Alexander Kotov (London, 1971): “When later I was busy writing this book I approached Botvinnik and asked him to tell me what he did when his opponent was thinking. The former world title-holder replied in much the following terms: Basically I do divide my thinking into two parts. When my opponent’s clock is going I discuss general considerations in an internal dialogue with myself. When my own clock is going I analyse concrete variations.” Botvinnik raccomandava di usare il tempo a disposizione dell’avversario per eseguire valutazioni di tipo strategico e posizionale e il nostro tempo per eseguire i necessari calcoli tattici che ci porteranno a giocare la nostra mossa. “Chess is mental torture” – Garry Kasparov Kasparov, che era un allievo di Botvinnik ha probabilmente ereditato questo metodo di pensiero alla scacchiera: considerazioni generali di tipo strategico durante la pensata dell’avversario e calcoli tattici nel proprio tempo. Non c’è mai riposo alla scacchiera, gli Scacchi sono una tortura mentale. Iniziamo a vedere cosa fare quindi Quando scorre il tempo del nostro avversario Valutazione Strategica La Tattica è al servizio della Strategia, ovvero la Tattica implementa la Strategia. -

Margate Chess Congress (1923, 1935 – 1939)

Margate Chess Congress (1923, 1935 – 1939) Margate is a seaside town and resort in the district of Thanet in Kent, England, on the coast along the North Foreland and contains the areas of Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay and Westbrook. Margate Clock Tower. Oast House Archive Margate, a photochrom print of Margate Harbour in 1897. Wikipedia The chess club at Margate, held five consecutive international tournaments from spring 1935 to spring 1939, three to five of the strongest international masters were invited to play in a round robin with the strongest british players (including Women’s reigning World Championne Vera Menchik, as well as British master players Milner-Barry and Thomas, they were invited in all five editions!), including notable "Reserve sections". Plus a strong Prequel in 1923. Record twice winner is Keres. Capablanca took part three times at Margate, but could never win! Margate tournament history Margate 1923 Kent County Chess Association Congress, Master Tournament (Prequel of the series) 1. Grünfeld, 2.-5. Michell, Alekhine, Muffang, Bogoljubov (8 players, including Réti) http://storiascacchi.altervista.org/storiascacchi/tornei/1900-49/1923margate.htm There was already a today somehow forgotten Grand Tournament at Margate in 1923, Grünfeld won unbeaten and as clear first (four of the eight invited players, namely Alekhine, Bogoljubov, Grünfeld, and Réti, were then top twelve ranked according to chessmetrics). André Muffang from France (IM in 1951) won the blitz competition there ahead of Alekhine! *********************************************************************** Reshevsky playing a simul at age of nine in the year 1920 The New York Times photo archive Margate 1st Easter Congress 1935 1. -

Contents Chess Mag - 21 6 10 21/06/2020 13:57 Page 3

01-01 Cover - July 2020_Layout 1 21/06/2020 14:21 Page 1 02-02 New in Chess advert_Layout 1 21/06/2020 14:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 21/06/2020 13:57 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Maria Emelianova..........................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the leading chess photographer and streamer Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Enter the Dragon .................................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Top seeds China proved too strong in FIDE’s Nations Cup Subscription Rates: How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................12 United Kingdom Daniel King examines Yu Yangyi’s key win for China 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Dubov Delivers...................................................................................................16 3 year (36 issues) £125 Lindores went online, with rapid experts Carlsen, Nakamura & Dubov Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 It’s All in the Timing.........................................................................................22 2 year -

Painter and Writer. Grob Was a Leading Swiss Player from Th

Grob Henry (04.06.1904 - 05.07.1974) Swiss International Master (1950, inauguration year of FIDE titles). Painter and writer. Grob was a leading swiss player from the 1930s to 1950s, and Swiss Champion in 1939 and 1951. Best results: Barcelona 1935, 3rd; Ostende 1936, 2nd, Ostende 1937, 1-3rd (first on tie-break, alongside with Fine and Keres, ahead of Landau, List, Koltanowski, Tartakower, 10 players; tournament winner Grob beat both, Fine and Keres!), Hastings 1947/48, 2nd-4th (Szabo won) He played multiple matches against strong opposition: He lost to Salomon Flohr (1½-4½) in 1933, beat Jacques Mieses (4½-1½) in 1934, drew with George Koltanowski (2-2), lost to Lajos Steiner 3-1 in 1935, lost to Max Euwe (½-5½) in 1947, lost to Miguel Najdorf (1-5) in 1948, lost to Efim Bogoljubow (2½-4½) in 1949 and to Lodewejk Prins (1½-4½) in 1950 (selection of matches). A participant in the Olympiads of 1927, 1935 and 1952. Addict of the opening 1.g4 (Grob’s attack”) which was deeply analysed in his book Angriff published in 1942. During the period 1940-1973, he was the editor of the chess column published in “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”. Author of “Lerne Schach spielen” (Zürich, 1945, reprinted many times). A professional artist, Grob has published Henry Grob the Artist, a book containing portraits of Grandmasters against whom he played (note: Grob writes his prename with an “y”, not an “i”). Famous game: Flohr, Salo - Grob, Henry Arosa match Arosa (1), 1933 1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 c5 3.dxc5 e6 4.e4 Bxc5 5.Bb5+ Nc6 6.exd5 exd5 7.O-O Nge7 8.Nbd2 O-O 9.Nb3 Bd6 -

Vera Menchik - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Vera Menchik from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

3/29/2015 Vera Menchik - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Vera Menchik From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Vera Menchik (Czech: Věra Menčíková; Russian: Ве́ра Фра́нцевна Ме́нчик Vera Frantsevna Menčik; 16 Vera Menchik February 1906 – 27 June 1944) was a British-Czech chess player who gained renown as the world's first women's chess champion. She also competed in chess tournaments with some of the world's leading male chess masters, defeating many of them, including future World Champion Max Euwe. Contents 1 Early life 2 Women's World Championships 3 International tournament results 4 The "Vera Menchik Club" 5 Late life and death 6 Notable chess games Full name Věra Menčíková 7 Notes Country Russian Empire 8 External links Soviet Union Czechoslovakia United Kingdom Early life Born 16 February 1906 Moscow, Russian Empire Her father, František Menčík, was born in Bystra nad 27 June 1944 (aged 38) Jizerou, Bohemia, while her mother, Olga Illingworth (c. Died Clapham, London, United 1885–1944[1]), was English. He was the manager of several Kingdom estates owned by the nobility in Russia, and his wife was a governess of the children of the estate owner. Women's World 1927–44 Champion Vera Menchik was born in Moscow in 1906. Her sister Olga Menchik was born in 1907. When she was nine years old her father gave her a chess set and taught her how to play. When she was 15 her school club organised a chess tournament and she came second. After the Revolution her father lost a mill he owned and eventually also the big house where the family lived. -

THE MATCH of the CENTURY USSR Vs. WORLD Th 50 Anniversary Edition

Tigran Petrosian Aleksandar Matanović THE MATCH OF THE CENTURY USSR vs. WORLD th 50 Anniversary Edition Edited and revised by Douglas Griffin and Igor Žveglić Authors Tigran Petrosian Aleksandar Matanović Editorial board Vitomir Božić, Douglas Griffin, Branko Tadić, Igor Žveglić Design Miloš Majstorović Editing and Typesetting Katarina Tadić Editor-in-chief GM Branko Tadić General Manager Vitomir Božić President GM Aleksandar Matanović © Copyright 2020 Šahovski informator All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. No part of the Chess Informant system (classification of openings, endings and combinations, system of signs, etc.) may be used in other publications without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-86-7297-108-8 Publisher Šahovski informator 11001 Beograd, Francuska 31, Srbija Phone: (381 11) 2630-109 E-mail: [email protected], Internet: https://www.sahovski.com Contents SYSTEM OF SIGNS [ 4 ] Foreword [ 5 ] Introduction: Half a century ago [ 9 ] Articles in The Soviet & Russian press [ 11 ] M. A. Beilin Carnations for Victory over the World Team - The Submerged Reefs of the ‘Match of the Century’ [ 11 ] A. B. Roshal Ahead – A Great Match [ 14 ] B. M. Kažić The Match of the Century, Day by Day [ 16 ] A. B. Roshal Against a Blue Background [ 23 ] Board-by-board – player profiles and -

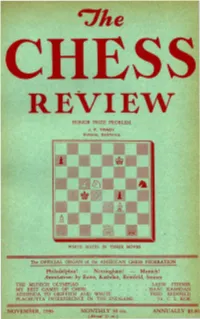

Munich! Annotations by Euwe, Kashdan, Reinfeld. Steiner the MUNICH OLYMPIAD

• HONOR PRIZE PROBLEM • J, F, TRACY Ontario, California • , • WHITE MATES IN THREE MOVES . Philadelphia! - Nottingham! - Munich! Annotations by Euwe, Kashdan, Reinfeld. Steiner THE MUNICH OLYMPIAD . - LAJOS STEINER MY BEST GAMES OF CHESS . • • _ ISAAC KASHDAN ADDENDA TO GRIFFITH AND WHITE • .. FRED REINFELD PLACHUTTA INTERFERENCE IN THE ENDGAME . • . TH. C. r., KOK NOVEMBER, 1936 MONTI:ILY 30 CtS. ANNUALLY $3.00 (Abro4J jJ m.)' _____________ ?he Do Your Share! The first annual report of the American Chess Federation reveals a record of accom. plishment anJ a pIOwam for the future thar merits the cooper:ltion of ;ti l chessplayers. Things that were done : REVIEW A yeal'book comprising the stOry of the 1935 :-'fi]waukl'1' Tournament was published. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE ~50 new Individual and 12 new Club Members AMERICAN CHESS FEDERATION were enrolled. Two bulletin ~ \\'('1'(' Issued to fammarize chessplayers with t he wot'k of the A. C. F. ISRAEL A. HOROWITZ, Editor Over 3,000 copie8 of eac h bulletin were dlstrl· S. S. COHEN, Managing Editor buted among m embers and non· members. THE CHESS REVIl<~W was enlisted as the FRED REINFELD, Auociate Editor Olliclal Organ of the l<~ ede ration to keep the wOI'k of thc J<'erl cration conUnually before the BARNIE F. WINKELMAN, Associafe Editor phe.>;!) public. R. CHENEY, Problelll Editor AWOl-king arrangemenl wa~ consummated BERTRAM KADISH, Art Director with the Natloual Recreation Association. This agreement will have the most far reaching and permanent influence on the status of eh,"_ The 37th a nnual toUnlament 01' the A. -

Savielly Tartakower, Een Bewogen Leven

Savielly Tartakower, een bewogen leven – door Dirk Goes – Savielly Grigorevitsj Tartakower werd geboren op 22 februari 1887 in Rostov aan de Don (tegenwoordig Oekraïne, des- tijds Russisch grondgebied) uit Pools/Oostenrijkse ouders van joodse origine. Schaken leerde hij op 10-jarige leeftijd van zijn vader. Zijn middelbare schooltijd bracht hij door in Geneve, waar hij het gymnasium doorliep. Na het behalen van zijn eindexamen in 1904 vertrok hij naar Wenen, om daar aan de universiteit rechten te studeren. In 1909 promoveerde hij tot doctor. Wenen was in die tijd het mekka van het schaken. De Wiener Schachklub, die in Baron Albert von Rothschild zijn voor- zitter had, en in de schaker/bankier Ignatz von Kolisch een steenrijke maecenas, speelde in twee verdiepingen van een groot gebouw, had een eigen restaurant, en telde maar liefst 700 leden. Beroemde schakers als Schlechter, Grünfeld, Maroczy, Reti, Vidmar en Teichmann schaakten er vrijwel elke dag. In deze wufte ambiance groeide Tartakower op als schaker, en de successen kwamen snel. In 1905 won hij het toernooi van Wenen en een jaar later was hij de sterkste in Nürnberg. Tartakower-Post, Mannheim 1914, met de Duitse meester Carls als aandachtig toeschouwer. Persoonlijk leed bleef hem niet bespaard. In 1911 werden zijn ouders vermoord tijdens een pogrom, ondanks dat ze zich enkele jaren daarvoor tot het katholicisme hadden bekeerd, en zijn broer Arthur, officier in het Oostenrijks/Hongaarse leger, sneuvelde bij Katowice op een van de vele slagvelden van de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Tartakower diende in hetzelfde leger, raakte gewond en herstelde volledig. Tartakower was een veelzijdig man.