Esperance Rock, Southern Kermadec Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muelleria Vol 32, 2014

Muelleria 33: 85–95 Published online in advance of the print edition, 21 April 2015. Nomenclature, variation and hybridisation in Rough Blown-grass (Poaceae: Lachnagrostis) Austin J. Brown National Herbarium of Victoria, Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra 3141, Victoria, Australia; tel: +61 3 9252 2300; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Abstract Variation in Rough Blown-grass (also known as Ruddy, Even or Meagre The name Lachnagrostis scabra ‘(P. Blown-grass) has been previously examined by Brown (2006) with the Beauv.) Nees ex Steud.’ for Rough Blown-grass is found to be a result that Lachnagrostis aequata (Nees) S.W.L.Jacobs (syn. Agrostis misapplication of Lachnagrostis scabra aequata Nees) and L. scabra ‘(P.Beauv.) Nees ex Steud.’ (syn. Agrostis scabra Nees ex Steud. (currently known R.Br. non Willd.) were considered to be the same taxon. In addition, it was as Agrostis pilosula Trin.): an Asiatic found that the name L. aequata had been misapplied to a Tasmanian taxon not found in Australia. The montane taxon, which was subsequently described as L. morrisii A.J.Br. correct name for Rough Blown-grass is Lachnagrostis rudis (Roem. & Schult.) Recent doubt expressed in Tropicos (2014) and APC (2014) concerning Trin. A dwarf form of the species the status of Vilfa scabra P.Beauv. as a new name or a new combination from Flinders Island is described as for A. scabra Willd. or A. scabra R.Br. respectively, has initiated a closer L. rudis subsp. nana A.J.Br., based examination of the name L. scabra Nees ex Steud. -

Lachnagrostis Billardierei Subsp. Billardierei

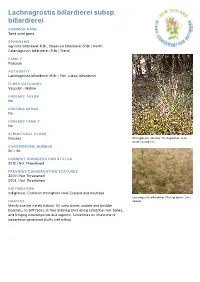

Lachnagrostis billardierei subsp. billardierei COMMON NAME Sand wind grass SYNONYMS Agrostis billardierei R.Br., Deyeuxia billardierei (R.Br.) Kunth, Calamagrostis billardierei (R.Br.) Steud. FAMILY Poaceae AUTHORITY Lachnagrostis billardierei (R.Br.) Trin. subsp. billardierei FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON No ENDEMIC GENUS No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Grasses Whangapoua, January. Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 56 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened DISTRIBUTION Indigenous. Common throughout New Zealand and Australia Lachnagrostis billardierei. Photographer: John HABITAT Sawyer Mainly coastal (rarely inland). On sand dunes, cobble and boulder beaches, on cliff faces, in free draining sites along estuarine river banks, and fringing coastal ponds and lagoons. Sometimes on limestone or calcareous sandstone bluffs well inland. FEATURES Stiffly tufted, glaucous to bluish-green perennial grass, 100-600 mm tall, with capillary-branched panicles sometimes overtopped by leaves. Branching intravaginal. Leaf-sheath papery, with wide membranous margins, closely striate, smooth but sometimes scaberulous above on nerves, light brown to amber. Ligule 1.0-4.5 mm, tapered above, entire to erose, undersides scabrid. Leaf-blade 50-240 x 2.5-10.0 mm, flat, harsh, scaberulous on ribs and on margins throughout, more or less abruptly narrowed to firm, more or less blunt, more or less cucullate apex. Culm 40-400 mm, erect, or decumbent at base, included within uppermost leaf-sheath, internodes densely finely scabrid. Panicle 60-240 x 100-240 mm, purple-green to wine-red, lax, with long, whorled, ascending branches, later spreading and panicle becoming as broad as long; rachis and branches scaberulous, spikelets single at tips of ultimate panicle branchlets, on pedicels thickened above. -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Functional Role of Betalains in Disphyma Australe Under Salinity Stress

FUNCTIONAL ROLE OF BETALAINS IN DISPHYMA AUSTRALE UNDER SALINITY STRESS BY GAGANDEEP JAIN A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington In fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2016) i “ An understanding of the natural world and what’s in it is a source of not only a great curiosity but great fulfillment” -- David Attenborough ii iii Abstract Foliar betalainic plants are commonly found in dry and exposed environments such as deserts and sandbanks. This marginal habitat has led many researchers to hypothesise that foliar betalains provide tolerance to abiotic stressors such as strong light, drought, salinity and low temperatures. Among these abiotic stressors, soil salinity is a major problem for agriculture affecting approximately 20% of the irrigated lands worldwide. Betacyanins may provide functional significance to plants under salt stress although this has not been unequivocally demonstrated. The purpose of this thesis is to add knowledge of the various roles of foliar betacyanins in plants under salt stress. For that, a series of experiments were performed on Disphyma australe, which is a betacyanic halophyte with two distinct colour morphs in vegetative shoots. In chapter two, I aimed to find the effect of salinity stress on betacyanin pigmentation in D. australe and it was hypothesised that betacyanic morphs are physiologically more tolerant to salinity stress than acyanic morphs. Within a coastal population of red and green morphs of D. australe, betacyanin pigmentation in red morphs was a direct result of high salt and high light exposure. Betacyanic morphs were physiologically more tolerant to salt stress as they showed greater maximum CO2 assimilation rates, water use efficiencies, photochemical quantum yields and photochemical quenching than acyanic morphs. -

Agrostis Griffithiana (Poaceae: Agrostidinae)—Typification, a New Synonym and an Update of the Distribution in India

Phytotaxa 140 (1): 26–34 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.140.1.2 Agrostis griffithiana (Poaceae: Agrostidinae)—typification, a new synonym and an update of the distribution in India BEATA PASZKO1 & COLIN A. PENDRY2 1Department of Vascular Plant Systematics and Phytogeography, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Lubicz 46, 31-512 Kraków, Poland. E-mail: [email protected] 2Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20a Inverleith Row, Edinburgh, EH3 5LR, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Agrostis griffithiana (Poaceae: Agrostidinae) is typified, fully described and illustrated, and its distribution in northeast India is elucidated. A new synonym is identified, its circumscription and taxonomy is clarified and discussed, especially in relation to the similar species A. pilosula and A. munroana. Key words: Agrostis munroana, A. pilosula, A. wardii, Calamagrostis, Deyeuxia griffithii, NE India, nomenclature, taxonomy Introduction Agrostis Linnaeus (1753: 61), Calamagrostis Adanson (1763: 31), Deyeuxia Clarion ex Beauvois (1812: 43) and Lachnagrostis Trinius (1820: 128) are members of the subtribe Agrostidineae in the tribe Poeae in the subfamily Pooideae (Soreng et al. 2007, Saarela et al. 2010) of the Poaceae. These genera are notoriously problematic because they include several difficult species complexes and numerous hybrids (Howard et al. 2009, Paszko & Nobis 2010, Paszko 2011, Paszko & Ma 2011), and the most recent studies of the group highlighted numerous taxonomic and nomenclatural inconsistencies. Many of these difficulties were resolved by Paszko (2012b), Paszko & Soreng (2013), Paszko (2013), and Paszko et al. -

2016 Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania

A CENSUS OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF TASMANIA, INCLUDING MACQUARIE ISLAND MF de Salas & ML Baker 2016 edition Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Department of State Growth Tasmanian Vascular Plant Census 2016 A Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania, Including Macquarie Island. 2016 edition MF de Salas and ML Baker Postal address: Street address: Tasmanian Herbarium College Road PO Box 5058 Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005 UTAS LPO Australia Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005 Australia © Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Published by the Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery GPO Box 1164 Hobart, Tasmania 7001 Australia www.tmag.tas.gov.au Cite as: de Salas, M.F. and Baker, M.L. (2016) A Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania, Including Macquarie Island. (Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Hobart) www.tmag.tas.gov.au ISBN 978-1-921599-83-5 (PDF) 2 Tasmanian Vascular Plant Census 2016 Introduction The classification systems used in this Census largely follow Cronquist (1981) for flowering plants (Angiosperms) and McCarthy (1998) for conifers, ferns and their allies. The same classification systems are used to arrange the botanical collections of the Tasmanian Herbarium and by the Flora of Australia series published by the Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS). For a more up-to-date classification of the flora refer to The Flora of Tasmania Online (Duretto 2009+) which currently follows APG II (2003). This census also serves as an index to The Student’s Flora of Tasmania (Curtis 1963, 1967, 1979; Curtis & Morris 1975, 1994). Species accounts can be found in The Student’s Flora of Tasmania by referring to the volume and page number reference that is given in the rightmost column (e.g. -

Muelleria Vol 32, 2014

Muelleria 34: 23–46 Published online in advance of the print edition, 4 August 2015. A morphological search for Lachnagrostis among the South African Agrostis and Polypogon (Poaceae) Austin J. Brown Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, Birdwood Avenue, Private Bag 2000, South Yarra 3141, Victoria, Australia; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Abstract The grass subtribe Agrostidinae Fr. of tribe Poeae R.Br. contains 17 genera Three South African Agrostis L. taxa are transferred to Lachnagrostis Trin., as according to Soreng et al. (2007), of which Lachnagrostis Trin., Agrostis L. eriantha (Hack.) A.J.Br., L. huttoniae L. and Polypogon Desf. are three. Delimitation of these genera has (Hack.) A.J.Br. and L. polypogonoides often been problematic and no less so than in South Africa. Despite a (Stapf) A.J.Br. on the basis of high number of recent studies, the phylogeny of the Poeae is still only partly palea to lemma length ratios and resolved (Soreng et al. 2007; Quintanar et al. 2007; Schneider et al. 2009; a lack of a trichodium net pattern on the lemma epidermis. However, Saarela et al. 2010). In addition, these phylogenies have not included the lemmas of L. barbuligera var. adequate representation of the complete Agrostidinae. Until such barbuligera and A. barbuligera var. work is undertaken, morphological assessments have a role to play in longipilosa Gooss. & Papendorf have segregating species into circumscribed genera. a trichodium net and do not belong The genus Lachnagrostis includes 31 species endemic to Australia in Lachnagrostis. Instead, they are morphologically similar to a group (Jacobs & Brown 2009) and New Zealand (Edgar & Connor 2000). -

New Lachnagrostis (Poaceae) Taxa from South Australia and South-West Victoria A

New Lachnagrostis (Poaceae) taxa from South Australia and South-west Victoria A. J. Brown Primary Industries Research Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, 621 Sneydes Road, Werribee, Victoria 3030, Australia; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Abstract Lachnagrostis Trin. has only recently been accepted in Australia (Jacobs Unusual and indeterminate 2001, 2002, 2004); species in it having formerly been included in Agrostis populations of Lachnagrostis Trin. were examined, both as herbarium L. The majority of Lachnagrostis species grow in lowland habitats, in specimens and in the field. Some contrast to the largely montane habitats of endemic species of Agrostis of these entities were also studied (an exception being the widespread A. venusta Trin.). as potted plants grown from field Two species, L. aemula (R.Br.) Trin. and L. filiformis (G.Forst.) Trin. extend collected seed to determine if from lowland to upland environments but even across their lowland morphological departures from currently circumscribed taxa were the habitats, show a wide range of morphological forms (Walsh & Entwistle result of environmental change or 1994). To more closely investigate these forms, extensive collection could be concluded to be genetically and examination of lowland populations of Lachnagrostis in south-east based. Although vegetative Australia was undertaken across south-west Victoria and South Australia growth (particularly leaf width) from the early 1990s through to the present. Work with L. billardierei (R.Br.) was markedly increased by artificial S.W.L.Jacobs, L. punicea (A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh) S.W.L.Jacobs and L. robusta growth conditions, morphological characteristics of inflorescences, (Vickery) S.W.L.Jacobs established new combinations (Brown & Walsh spikelets and florets were largely 2000) and relationships among some of these taxa and with L. -

Co-Extinction of Mutualistic Species – an Analysis of Ornithophilous Angiosperms in New Zealand

DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES CO-EXTINCTION OF MUTUALISTIC SPECIES An analysis of ornithophilous angiosperms in New Zealand Sandra Palmqvist Degree project for Master of Science (120 hec) with a major in Environmental Science ES2500 Examination Course in Environmental Science, 30 hec Second cycle Semester/year: Spring 2021 Supervisor: Søren Faurby - Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences Examiner: Johan Uddling - Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences “Tui. Adult feeding on flax nectar, showing pollen rubbing onto forehead. Dunedin, December 2008. Image © Craig McKenzie by Craig McKenzie.” http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/sites/all/files/1200543Tui2.jpg Table of Contents Abstract: Co-extinction of mutualistic species – An analysis of ornithophilous angiosperms in New Zealand ..................................................................................................... 1 Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning: Samutrotning av mutualistiska arter – En analys av fågelpollinerade angiospermer i New Zealand ................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. Material and methods ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1 List of plant species, flower colours and conservation status ....................................... 7 2.1.1 Flower Colours ............................................................................................................. -

Illustration, Distribution and Cultivation of Lachnagrostis Robusta, L

Illustration, distribution and cultivation of Lachnagrostis robusta, L. billardierei and L. punicea (Poaceae) Austin J. Brown National Herbarium of Victoria, Private Bag 2000, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Victoria 3141, Australia; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction Illustrations are presented for Brown and Walsh (2000) published new combinations for some varieties Lachnagrostis robusta, L. billardierei of Agrostis billardierei R.Br. and A. aemula R.Br.: A. billardierei var. robusta subsp. billardierei, L. billardierei subsp. tenuiseta, L. punicea subsp. Vickery as A. robusta (Vickery) A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh, A. billardierei var. filifolia punicea and L. punicea subsp. filifolia Vickery as Agrostis punicea A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh var. filifolia (Vickery) A.J.Br. as a supplement to an earlier paper & N.G.Walsh, A. billardierei var. collicola D.I.Morris as A. collicola (D.I.Morris) (Brown and Walsh 2000) which A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh and A. aemula var. setifolia Vickery as A. punicea var. provided a taxonomic revision of punicea. Subsequently, Jacobs (2001, 2002, 2004) transferred these and these grasses. Distributions of a other related taxa to Lachnagrostis Trin. and raised the rank of varieties to number of these taxa within South Australia and Victoria are updated subspecies, thus: L. robusta (Vickery) S.W.L.Jacobs, L. billardierei (R.Br.) Trin. and the results of morphological and subsp. billardierei, L. billardierei subsp. tenuiseta (D.Morris) S.W.L.Jacobs, phenological observations under L. collicola (D.Morris) S.W.L.Jacobs, L. punicea (A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh) S.W.L.Jacobs nursery conditions are reported. -

Poaceae) with Distributional Novelties to the Italian Territory

Natural History Sciences. Atti Soc. it. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano, 6 (2): 29-36, 2019 DOI: 10.4081/nhs.2019.429 An annotated key to the species of Gastridium (Poaceae) with distributional novelties to the Italian territory Anna Scoppola Abstract - Gastridium is a Mediterranean-paleotropical genus of INTRODUCTION the Poaceae family, native to Italy. Species number and diversity were Gastridium P.Beauv. is a Mediterranean-paleotropi- imperfectly known until recent taxonomic updates on morphological and molecular basis that enhanced our knowledge of this taxon. The cal genus (Pignatti, 1982; Bolòs & Vigo, 2001) of the present contribution provides a complete key of the genus, encom- Poaceae family (subfamily Pooideae Benth., tribe Poeae passing the four currently known closely related species, G. lainzii, G. R.Br., subtribe Agrostidinae Fr.), sister of the monot- phleoides, G. scabrum, and G. ventricosum. The essential features of ypic, Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian genus Triplach- panicle, spikelets, and florets are specified and briefly discussed. Revi- ne Link (Clayton & Renvoize, 1986; Quintanar et al., sions of ancient and recent herbarium specimens provided three Italian 2007; Saarela & Graham, 2010; Soreng et al. 2015). It distributional novelties for G. phleoides concerning Liguria, Campania, and Puglia and two for G. scabrum concerning Liguria and Basilicata. is represented by few, somewhat similar, annual species In contrast, the distributional ranges of G. scabrum and G. lainzii in inhabiting ephemeral grasslands, shrubby pastures, gar- the W Mediterranean region remain poorly known and await further rigues, forest clearings, hedges, path sides (Scoppola investigations. & Cancellieri, 2019). According to Kellogg (2015), the genus comprises two traditionally well-known species Key words: Gastridium, identification key, Italy, new records, Spain, taxonomic characters. -

2019 Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania

A CENSUS OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF TASMANIA, INCLUDING MACQUARIE ISLAND MF de Salas & ML Baker 2019 edition Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Department of State Growth Tasmanian Vascular Plant Census 2019 A Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania, including Macquarie Island. 2019 edition MF de Salas and ML Baker Postal address: Street address: Tasmanian Herbarium College Road PO Box 5058 Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005 UTAS LPO Australia Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005 Australia © Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Published by the Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery GPO Box 1164 Hobart, Tasmania 7001 Australia https://www.tmag.tas.gov.au Cite as: de Salas, MF, Baker, ML (2019) A Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania, including Macquarie Island. (Tasmanian Herbarium, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart) https://flora.tmag.tas.gov.au/resources/census/ 2 Tasmanian Vascular Plant Census 2019 Introduction The Census of the Vascular Plants of Tasmania is a checklist of every native and naturalised vascular plant taxon for which there is physical evidence of its presence in Tasmania. It includes the correct nomenclature and authorship of the taxon’s name, as well as the reference of its original publication. According to this Census, the Tasmanian flora contains 2726 vascular plants, of which 1920 (70%) are considered native and 808 (30%) have naturalised from elsewhere. Among the native taxa, 533 (28%) are endemic to the State. Forty-eight of the State’s exotic taxa are considered sparingly naturalised, and are known only from a small number of populations. Twenty-three native taxa are recognised as extinct, whereas eight naturalised taxa are considered to have either not persisted in Tasmania or have been eradicated.