Lachnagrostis Adamsonii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muelleria Vol 32, 2014

Muelleria 33: 85–95 Published online in advance of the print edition, 21 April 2015. Nomenclature, variation and hybridisation in Rough Blown-grass (Poaceae: Lachnagrostis) Austin J. Brown National Herbarium of Victoria, Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra 3141, Victoria, Australia; tel: +61 3 9252 2300; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Abstract Variation in Rough Blown-grass (also known as Ruddy, Even or Meagre The name Lachnagrostis scabra ‘(P. Blown-grass) has been previously examined by Brown (2006) with the Beauv.) Nees ex Steud.’ for Rough Blown-grass is found to be a result that Lachnagrostis aequata (Nees) S.W.L.Jacobs (syn. Agrostis misapplication of Lachnagrostis scabra aequata Nees) and L. scabra ‘(P.Beauv.) Nees ex Steud.’ (syn. Agrostis scabra Nees ex Steud. (currently known R.Br. non Willd.) were considered to be the same taxon. In addition, it was as Agrostis pilosula Trin.): an Asiatic found that the name L. aequata had been misapplied to a Tasmanian taxon not found in Australia. The montane taxon, which was subsequently described as L. morrisii A.J.Br. correct name for Rough Blown-grass is Lachnagrostis rudis (Roem. & Schult.) Recent doubt expressed in Tropicos (2014) and APC (2014) concerning Trin. A dwarf form of the species the status of Vilfa scabra P.Beauv. as a new name or a new combination from Flinders Island is described as for A. scabra Willd. or A. scabra R.Br. respectively, has initiated a closer L. rudis subsp. nana A.J.Br., based examination of the name L. scabra Nees ex Steud. -

Lachnagrostis Billardierei Subsp. Billardierei

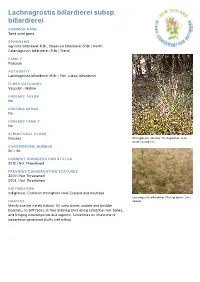

Lachnagrostis billardierei subsp. billardierei COMMON NAME Sand wind grass SYNONYMS Agrostis billardierei R.Br., Deyeuxia billardierei (R.Br.) Kunth, Calamagrostis billardierei (R.Br.) Steud. FAMILY Poaceae AUTHORITY Lachnagrostis billardierei (R.Br.) Trin. subsp. billardierei FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON No ENDEMIC GENUS No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Grasses Whangapoua, January. Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 56 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened DISTRIBUTION Indigenous. Common throughout New Zealand and Australia Lachnagrostis billardierei. Photographer: John HABITAT Sawyer Mainly coastal (rarely inland). On sand dunes, cobble and boulder beaches, on cliff faces, in free draining sites along estuarine river banks, and fringing coastal ponds and lagoons. Sometimes on limestone or calcareous sandstone bluffs well inland. FEATURES Stiffly tufted, glaucous to bluish-green perennial grass, 100-600 mm tall, with capillary-branched panicles sometimes overtopped by leaves. Branching intravaginal. Leaf-sheath papery, with wide membranous margins, closely striate, smooth but sometimes scaberulous above on nerves, light brown to amber. Ligule 1.0-4.5 mm, tapered above, entire to erose, undersides scabrid. Leaf-blade 50-240 x 2.5-10.0 mm, flat, harsh, scaberulous on ribs and on margins throughout, more or less abruptly narrowed to firm, more or less blunt, more or less cucullate apex. Culm 40-400 mm, erect, or decumbent at base, included within uppermost leaf-sheath, internodes densely finely scabrid. Panicle 60-240 x 100-240 mm, purple-green to wine-red, lax, with long, whorled, ascending branches, later spreading and panicle becoming as broad as long; rachis and branches scaberulous, spikelets single at tips of ultimate panicle branchlets, on pedicels thickened above. -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Agrostis Griffithiana (Poaceae: Agrostidinae)—Typification, a New Synonym and an Update of the Distribution in India

Phytotaxa 140 (1): 26–34 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.140.1.2 Agrostis griffithiana (Poaceae: Agrostidinae)—typification, a new synonym and an update of the distribution in India BEATA PASZKO1 & COLIN A. PENDRY2 1Department of Vascular Plant Systematics and Phytogeography, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Lubicz 46, 31-512 Kraków, Poland. E-mail: [email protected] 2Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20a Inverleith Row, Edinburgh, EH3 5LR, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Agrostis griffithiana (Poaceae: Agrostidinae) is typified, fully described and illustrated, and its distribution in northeast India is elucidated. A new synonym is identified, its circumscription and taxonomy is clarified and discussed, especially in relation to the similar species A. pilosula and A. munroana. Key words: Agrostis munroana, A. pilosula, A. wardii, Calamagrostis, Deyeuxia griffithii, NE India, nomenclature, taxonomy Introduction Agrostis Linnaeus (1753: 61), Calamagrostis Adanson (1763: 31), Deyeuxia Clarion ex Beauvois (1812: 43) and Lachnagrostis Trinius (1820: 128) are members of the subtribe Agrostidineae in the tribe Poeae in the subfamily Pooideae (Soreng et al. 2007, Saarela et al. 2010) of the Poaceae. These genera are notoriously problematic because they include several difficult species complexes and numerous hybrids (Howard et al. 2009, Paszko & Nobis 2010, Paszko 2011, Paszko & Ma 2011), and the most recent studies of the group highlighted numerous taxonomic and nomenclatural inconsistencies. Many of these difficulties were resolved by Paszko (2012b), Paszko & Soreng (2013), Paszko (2013), and Paszko et al. -

Muelleria Vol 32, 2014

Muelleria 34: 23–46 Published online in advance of the print edition, 4 August 2015. A morphological search for Lachnagrostis among the South African Agrostis and Polypogon (Poaceae) Austin J. Brown Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, Birdwood Avenue, Private Bag 2000, South Yarra 3141, Victoria, Australia; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Abstract The grass subtribe Agrostidinae Fr. of tribe Poeae R.Br. contains 17 genera Three South African Agrostis L. taxa are transferred to Lachnagrostis Trin., as according to Soreng et al. (2007), of which Lachnagrostis Trin., Agrostis L. eriantha (Hack.) A.J.Br., L. huttoniae L. and Polypogon Desf. are three. Delimitation of these genera has (Hack.) A.J.Br. and L. polypogonoides often been problematic and no less so than in South Africa. Despite a (Stapf) A.J.Br. on the basis of high number of recent studies, the phylogeny of the Poeae is still only partly palea to lemma length ratios and resolved (Soreng et al. 2007; Quintanar et al. 2007; Schneider et al. 2009; a lack of a trichodium net pattern on the lemma epidermis. However, Saarela et al. 2010). In addition, these phylogenies have not included the lemmas of L. barbuligera var. adequate representation of the complete Agrostidinae. Until such barbuligera and A. barbuligera var. work is undertaken, morphological assessments have a role to play in longipilosa Gooss. & Papendorf have segregating species into circumscribed genera. a trichodium net and do not belong The genus Lachnagrostis includes 31 species endemic to Australia in Lachnagrostis. Instead, they are morphologically similar to a group (Jacobs & Brown 2009) and New Zealand (Edgar & Connor 2000). -

New Lachnagrostis (Poaceae) Taxa from South Australia and South-West Victoria A

New Lachnagrostis (Poaceae) taxa from South Australia and South-west Victoria A. J. Brown Primary Industries Research Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, 621 Sneydes Road, Werribee, Victoria 3030, Australia; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Abstract Lachnagrostis Trin. has only recently been accepted in Australia (Jacobs Unusual and indeterminate 2001, 2002, 2004); species in it having formerly been included in Agrostis populations of Lachnagrostis Trin. were examined, both as herbarium L. The majority of Lachnagrostis species grow in lowland habitats, in specimens and in the field. Some contrast to the largely montane habitats of endemic species of Agrostis of these entities were also studied (an exception being the widespread A. venusta Trin.). as potted plants grown from field Two species, L. aemula (R.Br.) Trin. and L. filiformis (G.Forst.) Trin. extend collected seed to determine if from lowland to upland environments but even across their lowland morphological departures from currently circumscribed taxa were the habitats, show a wide range of morphological forms (Walsh & Entwistle result of environmental change or 1994). To more closely investigate these forms, extensive collection could be concluded to be genetically and examination of lowland populations of Lachnagrostis in south-east based. Although vegetative Australia was undertaken across south-west Victoria and South Australia growth (particularly leaf width) from the early 1990s through to the present. Work with L. billardierei (R.Br.) was markedly increased by artificial S.W.L.Jacobs, L. punicea (A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh) S.W.L.Jacobs and L. robusta growth conditions, morphological characteristics of inflorescences, (Vickery) S.W.L.Jacobs established new combinations (Brown & Walsh spikelets and florets were largely 2000) and relationships among some of these taxa and with L. -

Illustration, Distribution and Cultivation of Lachnagrostis Robusta, L

Illustration, distribution and cultivation of Lachnagrostis robusta, L. billardierei and L. punicea (Poaceae) Austin J. Brown National Herbarium of Victoria, Private Bag 2000, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Victoria 3141, Australia; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction Illustrations are presented for Brown and Walsh (2000) published new combinations for some varieties Lachnagrostis robusta, L. billardierei of Agrostis billardierei R.Br. and A. aemula R.Br.: A. billardierei var. robusta subsp. billardierei, L. billardierei subsp. tenuiseta, L. punicea subsp. Vickery as A. robusta (Vickery) A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh, A. billardierei var. filifolia punicea and L. punicea subsp. filifolia Vickery as Agrostis punicea A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh var. filifolia (Vickery) A.J.Br. as a supplement to an earlier paper & N.G.Walsh, A. billardierei var. collicola D.I.Morris as A. collicola (D.I.Morris) (Brown and Walsh 2000) which A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh and A. aemula var. setifolia Vickery as A. punicea var. provided a taxonomic revision of punicea. Subsequently, Jacobs (2001, 2002, 2004) transferred these and these grasses. Distributions of a other related taxa to Lachnagrostis Trin. and raised the rank of varieties to number of these taxa within South Australia and Victoria are updated subspecies, thus: L. robusta (Vickery) S.W.L.Jacobs, L. billardierei (R.Br.) Trin. and the results of morphological and subsp. billardierei, L. billardierei subsp. tenuiseta (D.Morris) S.W.L.Jacobs, phenological observations under L. collicola (D.Morris) S.W.L.Jacobs, L. punicea (A.J.Br. & N.G.Walsh) S.W.L.Jacobs nursery conditions are reported. -

Poaceae) with Distributional Novelties to the Italian Territory

Natural History Sciences. Atti Soc. it. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano, 6 (2): 29-36, 2019 DOI: 10.4081/nhs.2019.429 An annotated key to the species of Gastridium (Poaceae) with distributional novelties to the Italian territory Anna Scoppola Abstract - Gastridium is a Mediterranean-paleotropical genus of INTRODUCTION the Poaceae family, native to Italy. Species number and diversity were Gastridium P.Beauv. is a Mediterranean-paleotropi- imperfectly known until recent taxonomic updates on morphological and molecular basis that enhanced our knowledge of this taxon. The cal genus (Pignatti, 1982; Bolòs & Vigo, 2001) of the present contribution provides a complete key of the genus, encom- Poaceae family (subfamily Pooideae Benth., tribe Poeae passing the four currently known closely related species, G. lainzii, G. R.Br., subtribe Agrostidinae Fr.), sister of the monot- phleoides, G. scabrum, and G. ventricosum. The essential features of ypic, Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian genus Triplach- panicle, spikelets, and florets are specified and briefly discussed. Revi- ne Link (Clayton & Renvoize, 1986; Quintanar et al., sions of ancient and recent herbarium specimens provided three Italian 2007; Saarela & Graham, 2010; Soreng et al. 2015). It distributional novelties for G. phleoides concerning Liguria, Campania, and Puglia and two for G. scabrum concerning Liguria and Basilicata. is represented by few, somewhat similar, annual species In contrast, the distributional ranges of G. scabrum and G. lainzii in inhabiting ephemeral grasslands, shrubby pastures, gar- the W Mediterranean region remain poorly known and await further rigues, forest clearings, hedges, path sides (Scoppola investigations. & Cancellieri, 2019). According to Kellogg (2015), the genus comprises two traditionally well-known species Key words: Gastridium, identification key, Italy, new records, Spain, taxonomic characters. -

Esperance Rock, Southern Kermadec Islands

www.aucklandmuseum.com The flora and vegetation of L’Esperance Rock, southern Kermadec Islands Peter J. de Lange Department of Conservation Abstract The flora and vegetation of L’Esperance Rock, Kermadec Islands, is described. L’Esperance has a flora of twelve plants (one pteridophyte, nine angiosperms, one liverwort, one moss). Fifteen lichens (14 identified to species level, one to genus level) are also reported here. The grass,Lachnagrostis billardierei subsp. billardierei, and the herbs, Lepidium oleraceum, Spergularia tasmanica, and Solanum nodiflorum, are additions to the vascular flora of L’Esperance Rock, and, aside from the Lepidium and Solanum, the others are also additions to the known flora of the Kermadec Islands. Ten lichens are additions to recorded mycobiota for L’Esperance Rock, and of these, seven are also new records for the Kermadec Islands. Three empirically derived plant associations are recognised: bare rock and cliff faces, lichen field and Disphyma turf. The impact of Cyclone Bune (which struck L’Esperance Rock at the 28 March 2011) on the vegetation of the Rock is discussed, and the role that cyclones may have in the turnover of island flora is briefly explored. The conservation status of the L’Esperance Rock endemic Senecio lautus subsp. esperensis is reviewed. Keywords Kermadec Islands; southern Kermadec Islands; L’Esperance Rock; flora; lichens; bryophytes; pteridophytes; angiosperms; plant associations; cyclone damage; island biogeography; Senecio lautus subsp. esperensis INTRODUCTION of rock platforms and wave-washed rock outcrops. Vascular plant vegetation is confined to the upper two L’Esperance Rock (4.86 ha, 70 m a.s.l., 31° 25' 52.03" thirds of the Rock, and is mostly concentrated along the S, 178° 53' 56.12"W; Fig. -

Publications by Surrey Jacobs: 1946–2009 (In Chronological Order) Anderson DJ, Jacobs SWL & Malik AR (1969) Studies on Structure in Plant Communities VI

Telopea 13(1–2): 2011 1 Publications by Surrey Jacobs: 1946–2009 (in chronological order) Anderson DJ, Jacobs SWL & Malik AR (1969) Studies on structure in plant communities VI. The significance of pattern evaluation in some Australian dry-land vegetation types. Australian Journal of Botany 17: 315–322. Jacobs SWL (1971) Systematic position of the genera Triodia R.Br. and Plectrachne Henr. (Gramineae). Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 96 (3): 175–185. Jacobs SWL (1973) Practical plant ecology: principles of measurement and sampling. Science Bulletin 18: 47–48. Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL & Vesk M (1973) The structure of the cells of the mesophyll and parenchymatous bundle sheath of the Gramineae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 66: 259–275. Jacobs SWL (1974) Ecological studies on the genera Triodia R.Br. and Plectrachne Henr. in Australia. Ph.D. thesis, University of Sydney. Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL & Vesk M (1975) Leaf structure in Chenopodiaceae. Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik 95: 226–255. Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL & Vesk M (1977) The ultrastructure of Kranz Cells in the family Cyperaceae. Botanical Gazette 138: 413–419. Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL & Vesk M (1978) Kranz cells and mesophyll in the Chenopodiales. Australian Journal of Botany 26: 683–698. Jacobs SWL & Chapman EA (1979) Photosynthetic responses in semi-arid environments. Pp. 41–53 in Graetz RD & Howes KMW (eds) Studies of the Australian Arid Zone. IV. Chenopod Shrublands. Proceedings of a Symposium held by the Rangelands Research Unit of the Division of Land Resources Management.(CSIRO, Melbourne) Raison JK, Chapman EA, Wright LC & Jacobs SWL (1979) Membrane lipid transitions: their correlation with the climatic distribution of plants. -

The Taxonomic Status of Lachnagrostis Scabra, L. Aequata and Other Related Grasses in Australia (Poaceae)

Muelleria 24: 111–136 (2006) The taxonomic status of Lachnagrostis scabra, L. aequata and other related grasses in Australia (Poaceae). Austin J Brown Primary Industries Research Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, 621 Sneydes Road, Werribee. Abstract Early descriptions and treatments of Lachnagrostis scabra (Beauv.) Nees ex. Steud.and L. aequata (Nees) S.W.L. Jacobs are examined and compared to current determinations of herbaria collections. The results of this study show a confusing array of nomenclature and inconsistency in descriptions given of these taxa. Additional assessment of a range of morphological characters on more than 100 specimens find coastal L. scabra and L. aequata to be inseparable, but taxonomically distinct from collections previously determined as L. scabra from inland Tasmania. The name L. scabra takes precedence for the coastal entity while the inland material is published as a new taxon, L. morrisii A.J. Brown and shown to be distinct from L. collicola (D. Morris) S.W.L. Jacobs. Further related and new taxa, L. scabra subsp. curviseta A.J. Brown from Victoria and L. nesomytica A.J. Brown subsp. nesomytica, L. nesomytica subsp. pseudofiliformis A.J. Brown and L. nesomytica subsp. paralia A.J. Brown from Western Australia are also described. Introduction There has long been uncertainty about the taxonomic relationship between Lachnagrostis scabra (syn. Agrostis rudis) and L. aequata (A. aequata). Early treatments had very few specimens on which to form judgements but with many collections being made over the last 50 years or so, the opportunity to more rigorously assess this situation is now possible. The current paper reports on a re-examination of the earliest published descriptions and on some detailed morphological assessment of the bulk of extant collections. -

Lachnagrostis Billardierei Subsp. Tenuiseta

Threatened Species Link www.tas.gov.au SPECIES MANAGEMENT PROFILE Lachnagrostis billardierei subsp. tenuiseta small-awn blowngrass Group: Magnoliophyta (flowering plants), Liliopsida (monocots), Poales, Poaceae Status: Threatened Species Protection Act 1995: rare Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: Not listed Endemic Found only in Tasmania Status: A complete species management profile is not currently available for this species. Check for further information on this page and any relevant Activity Advice. Key Points Important: Is this species in your area? Do you need a permit? Ensure you’ve covered all the issues by checking the Planning Ahead page. Important: Different threatened species may have different requirements. For any activity you are considering, read the Activity Advice pages for background information and important advice about managing around the needs of multiple threatened species. Further information Check also for listing statement or notesheet pdf above (below the species image). Cite as: Threatened Species Section (2021). Lachnagrostis billardierei subsp. tenuiseta (small-awn blowngrass): Species Management Profile for Tasmania's Threatened Species Link. https://www.threatenedspecieslink.tas.gov.au/Pages/Lachnagrostis-billardierei-subsp-tenuiseta.aspx. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania. Accessed on 1/10/2021. Contact details: Threatened Species Section, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, GPO Box 44, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, 7001. Phone (1300 368 550). Permit: A permit is required under the Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 to 'take' (which includes kill, injure, catch, damage, destroy and collect), keep, trade in or process any specimen or products of a listed species. Additional permits may also be required under other Acts or regulations to take, disturb or interfere with any form of wildlife or its products, (e.g.