Kenya's Constitution and Institutional Reforms After Political Violence 1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Urban Governance Tools

County Urban Governance Tools This map shows various governance and management approaches counties are using in urban areas Mandera P Turkana Marsabit P West Pokot Wajir ish Elgeyo Samburu Marakwet Busia Trans Nzoia P P Isiolo P tax Bungoma LUFs P Busia Kakamega Baringo Kakamega Uasin P Gishu LUFs Nandi Laikipia Siaya tax P P P Vihiga Meru P Kisumu ga P Nakuru P LUFs LUFs Nyandarua Tharaka Garissa Kericho LUFs Nithi LUFs Nyeri Kirinyaga LUFs Homa Bay Nyamira P Kisii P Muranga Bomet Embu Migori LUFs P Kiambu Nairobi P Narok LUFs P LUFs Kitui Machakos Kisii Tana River Nyamira Makueni Lamu Nairobi P LUFs tax P Kajiado KEY County Budget and Economic Forums (CBEFs) They are meant to serve as the primary institution for ensuring public participation in public finances in order to im- Mom- prove accountability and public participation at the county level. basa Baringo County, Bomet County, Bungoma County, Busia County,Embu County, Elgeyo/ Marakwet County, Homabay County, Kajiado County, Kakamega County, Kericho Count, Kiambu County, Kilifi County, Kirin- yaga County, Kisii County, Kisumu County, Kitui County, Kwale County, Laikipia County, Machakos Coun- LUFs ty, Makueni County, Meru County, Mombasa County, Murang’a County, Nairobi County, Nakuru County, Kilifi Nandi County, Nyandarua County, Nyeri County, Samburu County, Siaya County, TaitaTaveta County, Taita Taveta TharakaNithi County, Trans Nzoia County, Uasin Gishu County Youth Empowerment Programs in urban areas In collaboration with the national government, county governments unveiled -

Challenges and Prospects for Sustainable Water Supply for Kajiado Town, Kajiado County

CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS FOR SUSTAINABLE WATER SUPPLY FOR KAJIADO TOWN, KAJIADO COUNTY By MUKINDIA JOSPHAT MUTUMA N50/CTY/PT/22731/2012 A Research Project report submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Environmental Planning and Management in the School of Environmental Studies of Kenyatta University. April 2014 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for the award of a degree in any other university. Signature ………………………………………… Date……………………………… Mukindia Josphat Mutuma N50/CTY/PT/22731/2012 This research project has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors. Signature…………………………………………… Date…………………………….. Dr. Peter K. Kamau Department of Environmental Planning and Management Kenyatta University Signature…………………………………………… Date…………………………….. Mr. Charles Mong’are Department of Environmental Planning and Management Kenyatta University ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge the support and encouragement I have received from my supervisors Dr. Peter Kamau and Charles Mong’are and the invaluable guidance. I appreciate the support and input from Dr. Girma Begashwa, the Water Sanitation and Hygiene advisor at World Vision Eastern Africa Learning Center, Eng. Joffrey Cheruiyot, Eng. Job Kitetu, Geologist Francis Huhu, Mr Frank meme and Julius Munyao all of World Vision Kenya. I acknowledge the support given by staff of County government of Kajiado; among them Stephen Karanja, Juma and Dorcas of the Ministry of Environment, Natural Resources and Water, Peter Kariuki and Josphat of Ministry of Roads and public works. I also acknowledge the support from Elizabeth Lusimba from Water Resources Management Authority. I also appreciate the input by Welthungerhilfe’s head of project in Kajiado Mr. -

Out Patient Facilities for Nhif Supa Cover Baringo County Bomet County Bungoma County Busia County

OUT PATIENT FACILITIES FOR NHIF SUPA COVER BARINGO COUNTY BRANCH No HOSPITAL NAME POSTAL ADDRESS OFFICE 1 TIONYBEI MEDICAL CLINIC 396-30400, KABARNET KABARNET 2 BARINGO DISTRICT HOSPITAL (KABARNET) 21-30400, KABARNET KABARNET 3 REALE MEDICAL CENTRE-KABARNET 4694-30100, ELDORET KABARNET 4 KERIO HOSPITAL LTD 458-30400, KABARNET KABARNET 5 RAVINE GLORY HEALTH CARE SERVICES 612-20103, ELDAMA RAVINE KABARNET 6 ELDAMA RAVINE NURSING HOME 612-20103, ELDAMA RAVINE KABARNET 7 BARNET MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTRE 490-30400, KABARNET KABARNET BOMET COUNTY BRANCH No HOSPITAL NAME POSTAL ADDRESS OFFICE 1 CHELYMO MEDICAL CENTRE 37-20422 SILIBWET BOMET 2 KAPKOROS HEALTH CENTRE 20400 BOMET BOMET BUNGOMA COUNTY BRANCH No HOSPITAL NAME POSTAL ADDRESS OFFICE 1 CHWELE SUBCOUNTY HOSPITAL 202 - 50202 CHWELE BUNGOMA 2 LUMBOKA MEDICAL SERVICES 1883 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 3 WEBUYE HEALTH CENTRE 25 - WEBUYE BUNGOMA 4 ST JAMES OPTICALS 2141 50200 BUNGOMA 5 NZOIA MEDICAL CENTRE 471 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 6 TRINITY OPTICALS LIMITED PRIVATE BAG BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 7 KHALABA MEDICAL SERVICES 2211- 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 8 ARARAT MEDICAL CLINIC 332 KIMILILI BUNGOMA 9 SIRISIA SUBDISTRICT HOSPITAL 122 - 50208 SIRISIA BUNGOMA 10 NZOIA MEDICAL CENTRE - CHWELE 471 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 11 OPEN HEART MEDICAL CENTRE 388 - 50202 CHWELE BUNGOMA 12 ICFEM DREAMLAND MISSION HOSPITAL PRIVATE BAG KIMILILI BUNGOMA 13 EMMANUEL MISSION HEALTH CENTRE 53 - 50207 MISIKHU BUNGOMA 14 WEBUYE DISTRICT HOSPITAL 25 - 50205 BUNGOMA 15 ELGON VIEW MEDICAL COTTAGE 1747 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 16 FRIENDS -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.)

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXII—No. 87 NAIROBI, 15th May, 2020 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTE NOTICES—(Contd.) PAGE PAGE The National Transport and Safety Authority Act— The Physical and Land Use Planning Act—Completion of Appointment ...................................................................... 1880 Part Development Plan, etc ............................................... 1914–1915 The National Authority fro the Campaign Against Alcohol The Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act— and Drug Abuse Act—Appointment ............................... 1880 Environmental Impact Assessment Study Report ........... 1915–1924 The National Construction Authority Act—Appointment .... 1880 County Governments Notices ................................................. 1880, Disposal of Uncollected Goods ............................................... 1924–1925 1903–1911 Change of Names ..................................................................... 1925 The Land Registration Act—Issue of New Title Deeds, etc . 1880–1890, 1925 ----------------- The Land Act—Corrigendum, etc .......................................... 1890–1891 SUPPLEMENT Nos. 69, 70 and 72 The East African Community Management Act— Cessation of Warehousing Goods ............................. 1891 Legislative Supplements, 2020 The Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority—Fuel LEGAL NOTICE NO. PAGE Enegy Cost Charge ................................................... -

Kenya: Agricultural Sector

Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE GLOBAL PRACTICE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA AGRICULTURAL SECTOR RISK ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized Stephen P. D’Alessandro, Jorge Caballero, John Lichte, and Simon Simpkin WORLD BANK GROUP REPORT NUMBER 97887 NOVEMBER 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE GLOBAL PRACTICE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PAPER KENYA Agricultural Sector Risk Assessment Stephen P. D’Alessandro, Jorge Caballero, John Lichte, and Simon Simpkin Kenya: Agricultural Sector Risk Assessment © 2015 World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank Group or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank Group concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. World Bank Group encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clear- ance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone: 978-750-8400, fax: 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright .com/. -

Newsletter from East Africa

Newsletter from East Africa Disclaimer of liability: The purpose of this newsletter is to forward information our office collects from different sources. It’s a private and internal document sent to selected Belgian companies only. This document cannot be re-disseminated, published, recopied, quoted or go public. Neither the Embassy of Belgium, nor the Belgian Trade Agencies nor the office based in Nairobi, nor any of their employees, nor any company or person mentioned on the following pages, makes any warranty, express or implied, including the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. July 2019 Issue No 84 MISSION Belgian Business Mission to Kenya & Uganda with a focus on Construction from 03-09 November 2019. Details from [email protected] IN A GLANCE Microsoft Corp will invest $100 million (Sh10 billion) to open an Africa technology development centre with sites in Kenya and Nigeria over the next five years. (Daily Nation) Tanzania and Zambia have agreed to jointly build à refined products pipeline to transport petroleum between the two countries at a cost of 41.5 billion. (The East African) Tanzania Uganda, Rwanda and Kenya are among 15 countries set to receive a total of $200 million from the US towards combating HIV in young women. (The East African) KENYA The Aga Khan Academy Mombasa (AKA Mombasa) seeks to build & sustain a needs based Scholarship programme by partnering with Corporates through their CSR initiatives and like- minded individuals in a mission to provide these deserving students a chance at an exceptional transformative international education that will enhance their leadership capabilities to positively impact their communities. -

Herbivore Dynamics and Range Contraction in Kajiado County Kenya: Climate and Land Use Changes, Population Pressures, Governance, Policy and Human-Wildlife Conflicts

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] The Open Ecology Journal, 2014, 7, 9-31 9 Open Access Herbivore Dynamics and Range Contraction in Kajiado County Kenya: Climate and Land Use Changes, Population Pressures, Governance, Policy and Human-wildlife Conflicts Joseph O. Ogutu1,2,*, Hans-Peter Piepho1, Mohammed Y. Said2 and Shem C. Kifugo2 1University of Hohenheim, Institute for Crop Science-340, 70599 Stuttgart, Germany 2International Livestock Research Institute, P.O. Box 30709-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Abstract: Wildlife populations are declining severely in many protected areas and unprotected pastoral areas of Africa. Rapid large-scale land use changes, poaching, climate change, rising population pressures, governance, policy, economic and socio-cultural transformations and competition with livestock all contribute to the declines in abundance. Here we analyze the population dynamics of 15 wildlife and four livestock species monitored using aerial surveys from 1977 to 2011 within Kajiado County of Kenya, with a rapidly expanding human population, settlements, cultivation and other developments. The abundance of the 14 most common wildlife species declined by 67% on average (2% / yr) between 1977 and 2011 in both Eastern (Amboseli Ecosystem) and Western Kajiado. The species that declined the most were buffalo, impala, wildebeest, waterbuck, oryx, hartebeest, Thomson’s gazelle and gerenuk in Eastern Kajiado (70% to 88%) and oryx, hartebeest, impala, buffalo, waterbuck, giraffe, eland and gerenuk in Western Kajiado (77% to 99%). Only elephant (115%) and ostrich (216%) numbers increased contemporaneously in Eastern and Western Kajiado, respectively. Cattle and donkey numbers also decreased on average by 78% in Eastern Kajiado and by 37% in Western Kajiado. -

Figure1: the Map of Kenya Showing 47 Counties (Colored) and 295 Sub-Counties (Numbered)

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Additional file 1: The county and sub counties of Kenya Figure1: The map of Kenya showing 47 counties (colored) and 295 sub-counties (numbered). The extents of major lakes and the Indian Ocean are shown in light blue. The names of the counties and sub- counties corresponding to the shown numbers below the maps. List of Counties (bold) and their respective sub county (numbered) as presented in Figure 1 1. Baringo county: Baringo Central [1], Baringo North [2], Baringo South [3], Eldama Ravine [4], Mogotio [5], Tiaty [6] 2. Bomet county: Bomet Central [7], Bomet East [8], Chepalungu [9], Konoin [10], Sotik [11] 3. Bungoma county: Bumula [12], Kabuchai [13], Kanduyi [14], Kimilili [15], Mt Elgon [16], Sirisia [17], Tongaren [18], Webuye East [19], Webuye West [20] 4. Busia county: Budalangi [21], Butula [22], Funyula [23], Matayos [24], Nambale [25], Teso North [26], Teso South [27] 5. Elgeyo Marakwet county: Keiyo North [28], Keiyo South [29], Marakwet East [30], Marakwet West [31] 6. Embu county: Manyatta [32], Mbeere North [33], Mbeere South [34], Runyenjes [35] Macharia PM, et al. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e003014. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003014 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health 7. Garissa: Balambala [36], Dadaab [37], Dujis [38], Fafi [39], Ijara [40], Lagdera [41] 8. -

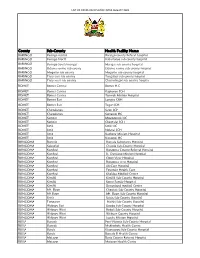

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

Seekers Living in Urban Areas in Light of Coronavirus (Covid-19)

IMPORTANT NOTICE TO ALL REFUGEES AND ASYLUM- SEEKERS LIVING IN URBAN AREAS IN LIGHT OF CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) On 15 March 2020 the Government of Kenya announced special measures to prevent further spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19). As of 27 March 2020, there is a daily curfew from 7 pm to 5 am. You are not allowed to leave your homes during this time, or you will be arrested. In addition, on 6 April 2020, the Government of Kenya announced that there will be no movement in or out of the Nairobi Metropolitan Area as of 6 April 2020 and the counties of Kilifi, Kwale and Mombasa as of 8 April 2020. Do not make any attempt to move in or out of these areas or you will be arrested. You can continue to move within the area where you are living, but ensure that you are wearing a facemask while in public places. For persons residing in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area, this includes Nairobi City County, Part of Kiambu County up to Chania River Bridge (Thika), including Rironi, Ndenderu, Kiambu Town; Part of Machakos County up to Athi-River, including Katani; Part of Kajiado County including Kitengela, Kiserian, Ongata Rongai and Ngong Town. Please do not move around more than absolutely necessary during the day time. If you have to move around, you must carry your registration documents with you at all times. Further, keep yourself updated on the guidance issued by the Government of Kenya and make sure that you adhere to it. Emergency assistance numbers ➢ For registration/documentation emergencies: Refugee Affairs Secretariat Shauri Moyo: 0772057770 -

Climate Risk Profile Kajiado County Highlights

Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Series Climate Risk Profile Kajiado County Highlights Kajiado County is predominantly semi-arid. Livestock rearing and crop farming are the main economic activities in the county. Crop farming is mainly in the southern and western parts of the county along rivers and springs. The agricultural sector employs 75% of the total population and provides nearly 40% of the county’s food requirements. The main climatic challenge facing the agricultural sector in Kajiado is drought. The frequency and severity of droughts in the county have resulted in crop failure and livestock losses and triggered severe food shortages in the past. In 2009 crop failure in the county reported at more than 90%, while livestock losses were in excess of 70% in most areas within the county. Current adaptation strategies include planting of drought-tolerant grasses/pastures, fodder conservation, irrigation, mass vaccination, livestock migrations, and rearing of livestock types adapted to drought. Stakeholders such as the Kenya Meteorological Department (KMD), National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (MoALF) offer off-farm services such as early warning and extension services. However, the low population density typical of pastoral areas combined with a lack of access roads makes the delivery of extension services difficult. Low literacy rates coupled with high poverty levels further compound the challenges brought about by climate change and variability; more than 53% of the population live below the poverty line. The high level of illiteracy among pastoralists of Kajiado County also hinders access to information, speed of recovery from climatic events, and constrains options for livelihood diversification.