Dutch Trading Networks in Early North America, 1624-1750

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 En 2 November 2001

Sponsoroverzicht (O)pa van der Stam, Hilversum A. C. Olij, Venhuizen A. C. X. Best A. Kroon van Baar, Enkhuizen A. Kuppers, Egmond aan de Hoef A.Distus Aad, Merel & Merijn van Keulen, Zwolle Adrie & Ria Brinkkemper, Enkhuizen Agaath Kruidenberg, Hoogkarspel Albert Niezen, Purmerend Alpha Tours, Hem ( www.alphatours.nl ) Andre Laan, Andijk Andries Zwaan Anette & Abdi, Tilburg Anja Dijkstra, Zwaag Anneke Buur, Hoorn Antoinette Steltenpool, Hoorn Arie Bronner, Schellinkhout Arie Groen, Wervershoof Arno & Yvonne Noorman, Enkhuizen Arno en Suus, ( www.happy-nomads.nl ) Ass.kantoor Neefjes, Wervershoof Astrid Timmerman-Karel Bert & Ank Asma, Enkhuizen Betty en Albert Rezee Betty Smet, Hilversum Bob & Nel Meijer, Koedijk Carel & Ute Akemann, de Knipe Carolien & Kedar Gauli, Velp Chris & Lina Tol Christien Lakenman, Enkhuizen Cindy Ellis, Alkmaar Cor van der Spruijt, Grootebroek Cora & Arend Jans, Enkhuizen Corrie Reijnders. ( www.shbn.nl ) Corry & Jan Braakman Corry de Jong en Henk, Dames Kok, Visser & Mulder, Bovenkarspel de Kiwani’s, de Valk BV, Hoorn Dekker fietsen, Enkhuizen Dhr. A. Stravers, Wervershoof Dhr. D. Boering, Wognum Dhr. E. Tholen Dhr. H. van Wielink, Bovenkarspel Dhr. J.J.M. Willemse, Capelle a/d IJssel. Dhr. N.G. Spigt, Wervershoof Dhr. P. Bakker, Heiloo Dhr. P. Botman, Schellinkhout Dhr. Th. Kunst, Hoogkarspel Dhr. vd Swaluw, Wervershoof Dhr.Sj. Mol, Wervershoof Dick & Ria Huyser Dick & Trudie Sijm. Andijk Dick Rijkelijkhuizen, Hillegom Dirk Waalboer, Benningbroek Do Ponsen, Julianadorp Dominique Dorreman, Hillegom Dragan Kloostra, Hoorn Ed en Tiny Verberne, Hoorn Ed Nieuweboer, Nibbixwoud Edelenbosch, A. Grootebroek Een Wereld van Mode te Bovenkarspel (www.dirkdewitmode.nl) Ellen & Martijn, Waddinxveen Ellen Reijnders, Koedijk Elly & Clemens Beemster, Venhuizen Elly Kiljan, Schagen Els Koerts, Hoorn Els Vunderink-Strating Enkhuizen voor Ontwikkelingssamenwerking, EvO Erik Monen, Hoorn Erik, Monique, Jorn en Amy de Lange, Enkhuizen Evelien Opdam Fam. -

Visitatierapport Raeflex

Stichting Woningbedrijf Velsen 2014 - 2017 Stichting Woningbedrijf Velsen Visitatierapport 2014 - 2017 Bennekom, 21 januari 2019 Colofon Raeflex Kierkamperweg 17B 6721 TE Bennekom Www.raeflex.nl Visitatiecommissie De heer ing. C. Hobo (voorzitter) De heer drs. A.H. Grashof (algemeen commissielid) Mevrouw drs. E.E.H. van Beusekom (secretaris) 2 Visitatierapport 2018 Stichting Woningbedrijf Velsen, Methodiek 5.0 | © Raeflex Raeflex Voorwoord Raeflex voert sinds 2002 professionele, onafhankelijke, externe visitaties bij woningcorporaties uit; in totaal rondde Raeflex bijna 330 visitatietrajecten af. Om onze onafhankelijke positie ten aanzien van woningcorporaties te waarborgen, verrichten wij geen overige advieswerkzaamheden. Onze visitaties worden merendeels uitgevoerd door externe visitatoren. Dit zijn professionals uit de wetenschap, de overheid en het bedrijfsleven die niet bij Raeflex in dienst zijn. Raeflex is geaccrediteerd door de Stichting Visitatie Woningcorporaties Nederland (SVWN). Sinds 2015 is de verplichting tot visitatie opgenomen in de Woningwet en in de Veegwet in 2017 is opgenomen dat de Aw de visitatietermijnen strikt gaat handhaven op vier jaar. Daarmee zien wij vanuit Raeflex dat visitatie een grotere rol gaat spelen in de toezichtinstrumenten die er voor woningcorporaties bestaan. Vanuit Raeflex willen we corporaties tijdens de visitaties meer bieden dan ‘afvinklijsten’ en het voldoen aan de verplichting. Visitatie is een waardevol instrument om corporaties te spiegelen op hun geleverde prestaties, de oordelen van belanghouders en om verbetertips mee te geven. Gelukkig biedt de visitatiemethodiek die wij sinds 2014 gebruiken mogelijkheden om toekomstgerichte aanbevelingen mee te geven en binnen de visitatiemethodiek maatwerk te leveren. Onze visitatierapporten zijn toekomstgericht en helder geschreven. Met veel genoegen leveren wij dit rapport op dat uitgaat van de visitatiemethodiek 5.0. -

5 the Da Vinci Code Dan Brown

The Da Vinci Code By: Dan Brown ISBN: 0767905342 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 CONTENTS Preface to the Paperback Edition vii Introduction xi PART I THE GREAT WAVES OF AMERICAN WEALTH ONE The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: From Privateersmen to Robber Barons TWO Serious Money: The Three Twentieth-Century Wealth Explosions THREE Millennial Plutographics: American Fortunes 3 47 and Misfortunes at the Turn of the Century zoART II THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTIONS, AND ENGINES OF WEALTH: Government, Global Leadership, and Technology FOUR The World Is Our Oyster: The Transformation of Leading World Economic Powers 171 FIVE Friends in High Places: Government, Political Influence, and Wealth 201 six Technology and the Uncertain Foundations of Anglo-American Wealth 249 0 ix Page 2 Page 3 CHAPTER ONE THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES: FROM PRIVATEERSMEN TO ROBBER BARONS The people who own the country ought to govern it. John Jay, first chief justice of the United States, 1787 Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits , but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. -Andrew Jackson, veto of Second Bank charter extension, 1832 Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress and touches even the ermine of the bench. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the Republic and endanger liberty. -

The Lovelace - Loveless and Allied Families

THE LOVELACE - LOVELESS AND ALLIED FAMILIES By FLORANCE LOVELESS KEENEY ROBERTSON, M.A. 2447 South Orange Drive Los Angeles, California This is Number ___ .of a Limited Edition Copyright 1952 by Florance Loveless Keeney Robertson, M.A. Printed and Bound in the United States by Murray & Gee, Inc., Culver City, Calif. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations V PREFACE vii The Loveless-Lovelace Family Coat of Arms X PART I-ENGLISH ANCESTRY OF THE FAMILY Chapter I-Earliest Records 1 Chapter II-The Hurley Branch 13 Chapter III-The Hever, Kingsdown and Bayford Lines 23 Chapter IV-The Bethersden Line . 37 Chapter IV-The Ancestors of All American Lovelace-Love- less Families . 43 PART II-AMERICAN FAMILIES Chapter I-Some Children of Sir William and Anne Barne Lovelace 51 Chapter 11-G-ov. Francis Lovelace of New York State and Some of his Descendants . 54 Chapter III-Loveless of Kentucky and Utah 59 Chapter IV-Jeremiah, Joseph and George Loveless of New York State 93 Chapter V-Lovelace and Loveless Families of Ohio, Ver- mont and Pennsylvania 108 Chapter VI-John Baptist Lovelace of Maryland 119 PART III-MISCELLANEOUS RECORDS Chapter I-English 133 Chapter II-American 140 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Lovelace-Goldwell Coat of Arms 3 Lovelace-Eynsham Coat of Arms 9 The Honorable Nevil Lovelace Shield _ 19 Lovelace-Peckham Coat of Arms 23 Lovelace-Harmon Coat of Arms 25 Lovelace-Clement Coat of Arms 27 Lovelace-Eynsham-Lewknor Coat of Arms 30 Florance Loveless Keeney and John Edwin Robertson . 101 Mary Mores (Goss) Loveless and Solomon Loveless 103 Cora Loveless 104 Memorial Window to Solomon and Mary Loveless . -

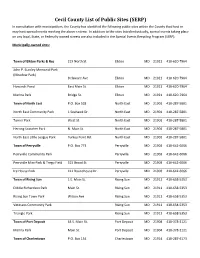

Cecil County List of Public Sites (SERP)

Cecil County List of Public Sites (SERP) In consultation with municipalities, the County has identified the following public sites within the County that host or may host special events meeting the above criteria. In addition to the sites listed individually, special events taking place on any local, State, or Federally-owned streets are also included in the Special Events Recycling Program (SERP). Municipally-owned sites: Town of Elkton Parks & Rec 219 North St. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 John P. Stanley Memorial Park (Meadow Park) Delaware Ave. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 Howards Pond East Main St. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 Marina Park Bridge St. Elkton MD 21921 410-620-7964 Town of North East P.O. Box 528 North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 North East Community Park 1 Seahawk Dr. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 Turner Park West St. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 Herring Snatcher Park N. Main St. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 North East Little League Park Turkey Point Rd. North East MD 21901 410-287-5801 Town of Perryville P.O. Box 773 Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Perryville Community Park Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Perryville Mini-Park & Trego Field 515 Broad St. Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Ice House Park 411 Roundhouse Dr. Perryville MD 21903 410-642-6066 Town of Rising Sun 1 E. Main St. Rising Sun MD 21911 410-658-5353 Diddie Richardson Park Main St. Rising Sun MD 21911 410-658-5353 Rising Sun Town Park Wilson Ave. -

1.1. the Dutch Republic

Cover Page The following handle holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation: http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61008 Author: Tol, J.J.S. van den Title: Lobbying in Company: Mechanisms of political decision-making and economic interests in the history of Dutch Brazil, 1621-1656 Issue Date: 2018-03-20 1. LOBBYING FOR THE CREATION OF THE WIC The Dutch Republic originated from a civl war, masked as a war for independence from the King of Spain, between 1568 and 1648. This Eighty Years’ War united the seven provinces in the northern Low Countries, but the young republic was divided on several issues: Was war better than peace for the Republic? Was a republic the best form of government, or should a prince be the head of state? And, what should be the true Protestant form of religion? All these issues came together in struggles for power. Who held power in the Republic, and who had the power to force which decisions? In order to answer these questions, this chapter investigates the governance structure of the Dutch Republic and answers the question what the circumstances were in which the WIC came into being. This is important to understand the rest of this dissertation as it showcases the political context where lobbying occurred. The chapter is complemented by an introduction of the governance structure of the West India Company (WIC) and a brief introduction to the Dutch presence in Brazil. 1.1. THE DUTCH REPUBLIC 1.1.1. The cities Cities were historically important in the Low Countries. Most had acquired city rights as the result of a bargaining process with an overlord. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700 Hugh Dunthorne Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83747-7 - Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700 Hugh Dunthorne Frontmatter More information Britain and the Dutch Revolt 1560–1700 England’s response to the Revolt of the Netherlands (1568–1648) has been studied hitherto mainly in terms of government policy, yet the Dutch struggle with Habsburg Spain affected a much wider commu- nity than just the English political elite. It attracted attention across Britain and drew not just statesmen and diplomats but also soldiers, merchants, religious refugees, journalists, travellers and students into the confl ict. Hugh Dunthorne draws on pamphlet literature to reveal how British contemporaries viewed the progress of their near neigh- bours’ rebellion, and assesses the lasting impact which the Revolt and the rise of the Dutch Republic had on Britain’s domestic history. The book explores affi nities between the Dutch Revolt and the British civil wars of the seventeenth century – the fi rst major challenges to royal authority in modern times – showing how much Britain’s chang- ing commercial, religious and political culture owed to the country’s involvement with events across the North Sea. HUGH DUNTHORNE specializes in the history of the early modern period, the Dutch revolt and the Dutch republic and empire, the his- tory of war, and the Enlightenment. He was formerly Senior Lecturer in History at Swansea University, and his previous publications include The Enlightenment (1991) and The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Britain and the Low Countries -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

Proquest Dissertations

FRONTIERS, OCEANS AND COASTAL CULTURES: A PRELIMINARY RECONNAISSANCE by David R. Jones A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary's University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Atlantic Canada Studues December, 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright David R. Jones Approved: Dr. M. Brook Taylor External Examiner Dr. Peter Twohig Reader Dr. John G. Reid Supervisor September 10, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46160-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46160-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Flatlands Tour Ad

Baltimore Bicycling Club's 36th Annual Delaware-Maryland Flatlands Tour Dedicated to the memory of Dave Coder (7/6/1955 - 2/14/2004) Saturday, June 17, 2006 Event Coordinator: Ken Philhower (410-437-0309 or [email protected]) Place: Bohemia Manor High School, 2755 Augustine Herman Highway (Rt. 213), Chesapeake City, MD Directions: From Baltimore, take I-95 north to exit 109A (Rt. 279 south) and go 3 miles to Elkton. Turn left at Rt. 213 south. Cross Rt. 40 and continue 6 miles to Chesapeake City. Cross the C&D Canal Bridge and continue 1 mile. Turn right at traffic light (flashing yellow on weekends) into Bohemia Manor High School. Please allow at least 1-1/2 hours to get there from Baltimore. (It's about 65 miles.) From Annapolis, take US Route 50/301 east across the Bay Bridge and continue 10 miles. At the 50-301 split, continue straight on Rt. 301 north (toward Wilmington) for 32 miles. Turn left on Rt. 313 north and go 3 miles to Galena, then go straight at the traffic light onto Rt. 213 north. Continue on Rt. 213 north for 13 miles (about 2 miles past the light at Rt. 310), then turn left at the traffic light (flashing yellow on weekends) into Bohemia Manor High School. Please allow at least 1 hour and 45 minutes to get there from Annapolis. (It's about 70 miles.) From Washington DC, take Beltway Exit 19A, US Route 50 East, 20 miles to Annapolis, then follow Annapolis directions above. From Wilmington, DE, take I-95 south to exit 1A, Rt. -

Van Rensselaer Family

.^^yVk. 929.2 V35204S ': 1715769 ^ REYNOLDS HISTORICAL '^^ GENEALOGY COLLECTION X W ® "^ iiX-i|i '€ -^ # V^t;j^ .^P> 3^"^V # © *j^; '^) * ^ 1 '^x '^ I It • i^© O ajKp -^^^ .a||^ .v^^ ^^^ ^^ wMj^ %^ ^o "V ^W 'K w ^- *P ^ • ^ ALLEN -^ COUNTY PUBLIC LIBR, W:^ lllillllli 3 1833 01436 9166 f% ^' J\ ^' ^% ^" ^%V> jil^ V^^ -llr.^ ^%V A^ '^' W* ^"^ '^" ^ ^' ?^% # "^ iir ^M^ V- r^ %f-^ ^ w ^ '9'A JC 4^' ^ V^ fel^ W' -^3- '^ ^^-' ^ ^' ^^ w^ ^3^ iK^ •rHnviDJ, ^l/OL American Historical Magazine VOL 2 JANUARY. I907. NO. I ' THE VAN RENSSELAER FAMILY. BY W. W. SPOONER. the early Dutch colonial families the Van OF Rensselaers were the first to acquire a great landed estate in America under the "patroon" system; they were among the first, after the English conquest of New Netherland, to have their possessions erected into a "manor," antedating the Livingstons and Van Cortlandts in this particular; and they were the last to relinquish their ancient prescriptive rights and to part with their hereditary demesnes under the altered social and political conditions of modem times. So far as an aristocracy, in the strict understanding of the term, may be said to have existed under American institu- tions—and it is an undoubted historical fact that a quite formal aristocratic society obtained throughout the colonial period and for some time subsequently, especially in New York, — the Van Rensselaers represented alike its highest attained privileges, its most elevated organization, and its most dignified expression. They were, in the first place, nobles in the old country, which cannot be said of any of the other manorial families of New York, although several of these claimed gentle descent.