A Conservation Timeline Milestones of the Model’S Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

Marine Director WCS Finaltor

JOB DESCRIPTION Director, Marine Conservation and Fisheries Wildlife Conservation Society Founded in 1895 as the New York Zoological Society The Wildlife Conservation Society seeks a Director of Marine Conservation and Fisheries, to be based at WCS headquarters in New York City. WCS has a long history of ocean exploration and conservation, including William Beebe’s 1934 record-setting bathysphere dive and Roger Payne’s extraordinary 1974 discovery of humpback whale songs. From these early roots, and reflecting the WCS focus on saving wildlife and wild places, WCS’ marine conservation efforts currently focus on four strategies: Marine Protected Areas, sustainable fisheries, marine mammals, and sharks and rays. Supporting these strategies, WCS maintains a strong commitment to applied marine scientific research and is building its capacity to leverage our impact through WCS’ New York Aquarium and other innovative partnerships. To deliver on these objectives at scale the Director oversees all WCS marine conservation efforts, including the implementation of marine conservation actions by ~250 marine conservation staff in Belize, Cuba, Nicaragua, Argentina, Chile, Gabon, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambiue, Madagascar, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, New York and the Arctic Beringia, as well as overseeing staff who coordinate global initiatives on marine species (cetaceans and sharks), climate, fisheries and marine policy. The program is staffed by a dynamic and committed team of field scientists based at sites around the world, and a directorate of six staff in New York. Position Objectives: * Direct WCS’s marine conservation programs across 9 global priority regions and all 5 oceans in Africa, Asia, Latin America and North America that largely focus on the establishment and management of marine protected areas, artisanal, and commercial fisheries, and the global conservation of marine mammals and sharks and rays. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

Macmillan History 9

Chapter 5 Making a nation HISTORY SKILLS In this chapter you will learn to apply the following historical skills: • explain the effects of contact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, categorising these effects as either intended or unintended • outline the migration of Chinese to the goldfields in Australia in the 19th century and attitudes towards the Chinese, as revealed in cartoons • identify the main features of housing, sanitation, transport, education and industry that influenced living and working conditions in Australia • describe the impact of the gold rushes (hinterland) on the development of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ • explain the factors that contributed to federation and the development of democracy in Australia, including defence concerns, the 1890s depression, nationalist ideals, egalitarianism and the Westminster system • investigate how the major social legislation of the new federal government—for example, invalid and old-age pensions and the maternity allowance scheme—affected living and working conditions in Australia. © Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority 2012 Federation celebrations in Centennial Park, Sydney, 1 January 1901 Inquiry questions 1 What were the effects of contact between European 4 What were the key events and ideas in the settlers in Australia and Aboriginal and Torres Strait development of Australian self-government and IslanderSAMPLE peoples when settlement extended? democracy? 2 What were the experiences of non-Europeans in 5 What significant legislation was passed in the Australia prior to the 1900s? period 1901–1914? 3 What were the living and working conditions in Australia around 1900? Introduction THE EXPERIENCE OF indigenous peoples, Europeans and non-Europeans in 19th-century Australia were very different. -

EAZA Bushmeat Campaign

B USHMEAT | R AINFOREST | T IGER | S HELLSHOCK | R HINO | M ADAGASCAR | A MPHIBIAN | C ARNIVORE | A PE EAZA Conservation Campaigns EAZA Bushmeat Over the last ten years Europe’s leading zoos and aquariums have worked together in addressing a variety of issues affecting a range of species and Campaign habitats. EAZA’s annual conservation campaigns have raised funds and promoted awareness amongst 2000-2001 millions of zoo visitors each year, as well as providing the impetus for key regulatory change. | INTRODUCTION | The first of EAZA's annual conservation campaigns addressed the issue of the unsustainable and illegal hunting and trade of threatened wildlife, in particular the great apes. Bushmeat is a term commonly used to describe the hunting and trade of wild meat. For the Bushmeat Campaign EAZA collaborated with the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) as an official partner in order to enhance the chances of a successful campaign. The Bushmeat Campaign can be regarded as the ‘template campaign’ for the EAZA conservation campaigns that followed over the subsequent ten years. | CAMPAIGN AIMS | Through launching the Bushmeat Campaign EAZA hoped to make a meaningful contribution to the conservation of great apes in the wild, particularly in Africa, over the next 20 to 50 years. The bushmeat trade was (and still is) a serious threat to the survival of apes in the wild. Habitat loss and deforestation have historically been the major causal factors for declining populations of great apes, but experts now agree that the illegal commercial bushmeat trade has surpassed habitat loss as the primary threat to ape populations. -

Chapter 4 Natural Resources and Environmental Constraints

Chapter 4 Natural Resources and Environmental Constraints PERSONAL VISION STATEMENTS “I want to live in a city that cares about air quality and the environment.” “Keep Birmingham beautiful, especially the water ways.” 4.1 CITY OF BIRMINGHAM COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PART II | CHAPTER 4 NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSTRAINTS GOALS POLICIES FOR DECISION MAKERS natural areas and conservation A comprehensive green infrastructure • Support the creation of an interconnected green infrastructure network that includes system provides access to and natural areas for passive recreation, stormwater management, and wildlife habitat. preserves natural areas and • Consider incentives for the conservation and enhancement of natural and urban environmentally sensitive areas. forests. Reinvestment in existing communities • Consider incentives for reinvestment in existing communities rather than conserves resources and sensitive “greenfields,” for new commercial, residential and institutional development. environments. • Consider incentives for development patterns and site design methods that help protect water quality, sensitive environmental features, and wildlife habitat. air and water quality The City makes every effort to • Support the development of cost-effective multimodal transportation systems that consistently meet clean air standards. reduce vehicle emissions. • Encourage use of clean fuels and emissions testing. • Emphasize recruitment of clean industry. • Consider incentives for industries to reduce emissions over time. • Promote the use of cost-effective energy efficient design, materials and equipment in existing and private development. The City makes every effort to • Encourage the Birmingham Water Works Board to protect water-supply sources consistently meet clean water located outside of the city to the extent possible. standards. • Consider incentives for development that protects the city’s water resources. -

Supplemental Wildlife Food Planting Manual for the Southeast • Contents

Supplemental Wildlife Food Planting Manual for the Southeast • Contents Managing Plant Succession ................................ 4 Openings ............................................................. 6 Food Plot Size and Placement ............................ 6 Soil Quality and Fertilization .............................. 6 Preparing Food Plots .......................................... 7 Supplemental Forages ............................................................................................................................. 8 Planting Mixtures/Strip Plantings ......................................................................................................... 9 Legume Seed Inoculation ...................................................................................................................... 9 White-Tailed Deer ............................................................................................................................... 10 Eastern Wild Turkey ............................................................................................................................ 11 Northern Bobwhite .............................................................................................................................. 12 Mourning Dove ................................................................................................................................... 13 Waterfowl ............................................................................................................................................ -

Effects of Global Warming on Wildlife and Human Health

Effects of Global Warming on Wildlife and Human Health Jennifer Lopez Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development I-Context Challenge 2 1.2 Effects of Global Warming on Health Effects of Global Warm- ing on Wildlife and Human Health Jennifer Lopez Based on a presentation by Dr. Camille Parmesan main picture of presentation Figure 1: Earth from Outer Space. Introduction of greenhouse emissions.”4 Finally in 2007, the Fourth IPCC Assessment report concluded Global warming is defined as “the increase that the “warming of the climate system is un- in the average measured temperature of the equivocal” and “is very likely [> 90% sure] due Earth’s near surface air and oceans”.1 For the to observed increases in anthropogenic green- past several decades scientists have docu- house gas concentrations.”5 Based on these mented multiple aspects of climate change, conclusions, many scientists and environmen- including rising surface air temperature, rising talists have focused their efforts on sustainable ocean temperature, changes in rain and snow- living and are pushing for energy alternatives fall patterns, declines in permanent snowpack which produce little or no carbon-dioxide to and sea ice, and a rise in sea level.2 Through reduce greenhouse gas emissions. their research, scientists have been able not only to document changes in climate and the Effects of temperature change physical environment, but have also docu- mented effects that this phenomenon is having Scientists have concluded that in the past 100 on the world’s ecosystems and species, many years, the Earth’s average air temperature has of which are negative. -

Wealth Mobility in the 1860S

Economics Working Papers 9-18-2020 Working Paper Number 20018 Wealth Mobility in the 1860s Brandon Dupont Western Washington University Joshua L. Rosenbloom Iowa State University, [email protected] Original Release Date: September 18, 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/econ_workingpapers Part of the Economic History Commons, Growth and Development Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Dupont, Brandon and Rosenbloom, Joshua L., "Wealth Mobility in the 1860s" (2020). Economics Working Papers: Department of Economics, Iowa State University. 20018. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/econ_workingpapers/113 Iowa State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, age, ethnicity, religion, national origin, pregnancy, sexual orientation, gender identity, genetic information, sex, marital status, disability, or status as a U.S. veteran. Inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies may be directed to Office ofqual E Opportunity, 3350 Beardshear Hall, 515 Morrill Road, Ames, Iowa 50011, Tel. 515 294-7612, Hotline: 515-294-1222, email [email protected]. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please visit lib.dr.iastate.edu. Wealth Mobility in the 1860s Abstract We offer new evidence on the regional dynamics of wealth holding in the United States over the Civil War decade based on a hand-linked random sample of wealth holders drawn from the 1860 census. Despite the wealth shock caused by emancipation, we find that patterns of wealth mobility were broadly similar for northern and southern residents in 1860. -

Nineteenth-Century Serial Fictions in Transnational Perspective, 1830S-1860S

Popular Culture – Serial Culture: Nineteenth-Century Serial Fictions in Transnational Perspective, 1830s-1860s University of Siegen, April 28-30, 2016 Conveners: Prof. Dr. Daniel Stein / Lisanna Wiele, M.A. North American Literary and Cultural Studies Recent publications such as Transnationalism and American Serial Fiction (Okker 2011) and Serialization in Popular Culture (Allen/van den Berg 2014) remind us that serial modes of storytelling, publication, and reception have been among the driving forces of modern culture since the first half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, as studies of Victorian serial fiction, the French feuilleton novel, and American magazine fiction indicate, much of what we take for granted as central features of contemporary serial fictions traces back to a particular period in the nineteenth century between the 1830s and the 1860s. This is the time when new printing techniques allowed for the mass publication of affordable reading materials, when literary authorship became a viable profession, when reading for pleasure became a popular pastime for increasingly literate and socially diverse audiences, and when previously predominantly national print markets became thoroughly international. These transformations enabled, and, in turn, were enabled by, the emergence of popular serial genres, of which the so-called city mystery novels are a paradigmatic example. In the wake of the success of Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris (1842-43), a great number of these city mysteries appeared across Europe (especially France, Great Britain, and Germany) and the United States, adapting the narrative formulas and basic storylines of Sue’s roman feuilleton to different cultural, social, economic, and political contexts. -

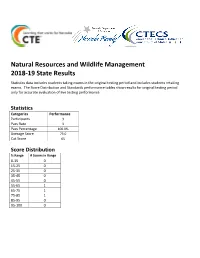

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33%