A Gag at the Bottom of a Bowl? Perceptions of Playfulness in Archaic and Classical Greece • Thomas Banchich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The eighth-century revolution Version 1.0 December 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: Through most of the 20th century classicists saw the 8th century BC as a period of major changes, which they characterized as “revolutionary,” but in the 1990s critics proposed more gradualist interpretations. In this paper I argue that while 30 years of fieldwork and new analyses inevitably require us to modify the framework established by Snodgrass in the 1970s (a profound social and economic depression in the Aegean c. 1100-800 BC; major population growth in the 8th century; social and cultural transformations that established the parameters of classical society), it nevertheless remains the most convincing interpretation of the evidence, and that the idea of an 8th-century revolution remains useful © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 THE EIGHTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION Ian Morris Introduction In the eighth century BC the communities of central Aegean Greece (see figure 1) and their colonies overseas laid the foundations of the economic, social, and cultural framework that constrained and enabled Greek achievements for the next five hundred years. Rapid population growth promoted warfare, trade, and political centralization all around the Mediterranean. In most regions, the outcome was a concentration of power in the hands of kings, but Aegean Greeks created a new form of identity, the equal male citizen, living freely within a small polis. This vision of the good society was intensely contested throughout the late eighth century, but by the end of the archaic period it had defeated all rival models in the central Aegean, and was spreading through other Greek communities. -

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

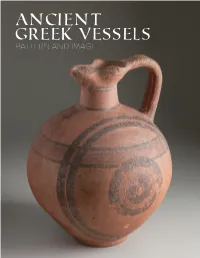

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Gillian Bevan Is an Actor Who Has Played a Wide Variety of Roles in West End and Regional Theatre

Gillian Bevan is an actor who has played a wide variety of roles in West End and regional theatre. Among these roles, she was Dorothy in the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of The Wizard of Oz, Mrs Wilkinson, the dance teacher, in the West End production of Billy Elliot, and Mrs Lovett in the West Yorkshire Playhouse production of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Gillian has regularly played roles in other Sondheim productions, including Follies, Merrily We Roll Along and Road Show, and she sang at the 80th birthday tribute concert of Company for Stephen Sondheim (Donmar Warehouse). Gillian spent three years with Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, and her Shakespearian roles include Polonius (Polonia) in the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre production of Hamlet (Autumn, 2014) with Maxine Peake in the title role. Gillian’s many television credits have included Teachers (Channel 4) in which she played Clare Hunter, the Headmistress, and Holby City (BBC1) in which she gave an acclaimed performance as Gina Hope, a sufferer from Motor Neurone Disease, who ends her own life in an assisted suicide clinic. During the early part of 2014, Gillian completed filming London Road, directed by Rufus Norris, the new Artistic Director of the National Theatre. In the summer of 2014 Gillian played the role of Hera, the Queen of the Gods, in The Last Days of Troy by the poet and playwright Simon Armitage. The play, a re-working of The Iliad, had its world premiere at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre and then transferred to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, London. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

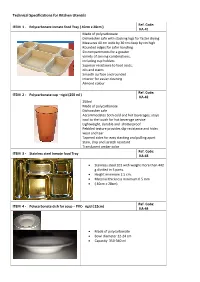

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter (1) The remnants of this government established the Republic of Ezo after losing the Boshin War. Two and a half centuries earlier, this government was founded after its leader won the Battle of Sekigahara against the Toyotomi clan. This government's policy of sakoku came to an end when Matthew Perry's Black Ships forced the opening of Japan through the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa. For ten points, name this last Japanese shogunate. ANSWER: Tokugawa Shogunate (or Tokugawa Bakufu) (2) Xenophon's Anabasis describes ten thousand Greek soldiers of this type who fought Artaxerxes II of Persia. A war named for these people was won by Hamilcar Barca and led to his conquest of Spain. Famed soldiers of this type include slingers from Rhodes and archers from Crete. Greeks who fought for Persia were, for ten points, what type of soldier that fought not for national pride, but for money? ANSWER: mercenary (prompt on descriptive answers) (3) The most prominent of the Townshend Acts not to be repealed in 1770 was a tax levied on this commodity. The Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver carried this commodity from England to the American colonies. The Intolerable Acts were passed in response to the dumping of this commodity into a Massachusetts Harbor in 1773 by members of the Sons of Liberty. For ten points, identify this commodity destroyed in a namesake Boston party. ANSWER: tea (accept Tea Act; accept Boston Tea Party) (4) This location is the setting of a photo of a boy holding a toy hand grenade by Diane Arbus. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology Medieval Pottery Research Group Prehistoric Ceramics Research Group Study Group for Roman Pottery Draft 4 October 2015 CONTENTS Section 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Aims 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Structure 2 1.4 Project Tasks 2 1.5 Using the Standard 5 Section 2 The Standard 6 2.1 Project Planning 6 2.2 Collection and Processing 8 2.3 Assessment 11 2.4 Analysis 13 2.5 Reporting 17 2.6 Archive Creation, Compilation and Transfer 20 Section 3 Glossary of Terms 23 Section 4 References 25 Section 5 Acknowledgements 27 Appendix 1 Scientific Analytical Techniques 28 Appendix 2 Approaches to Assessment 29 Appendix 3 Approaches to Analysis 33 Appendix 4 Approaches to Reporting 39 1. INTRODUCTION Pottery has two attributes that lend it great potential to inform the study of human activity in the past. The material a pot is made from, known to specialists as the fabric, consists of clay and inclusions that can be identified to locate the site at which a pot was made, as well as indicate methods of manufacture and date. The overall shape of a pot, together with the character of component parts such as rims and handles, and also the technique and style of decoration, can all be studied as the form. This can indicate when and how a pot was made and used, as well as serving to define cultural affinities. The interpretation of pottery is based on a detailed characterisation of the types present in any group, supported by sound quantification and consistent approaches to analysis that facilitate comparison between assemblages. -

Fulminante-2012-Ethnicity-Chapter

- LANDSCAPE, ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY LANDSCAPE, ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY IN THE ARCHAIC MEDITERRANEAN AREA LANDSCAPE, ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY The main concern of this volume is the multi-layered IN THE ARCHAIC MEDITERRANEAN AREA concept of ethnicity. Contributors examine and contextualise contrasting definitions of ethnicity and identity as implicit in two perspectives, one from the classical tradition and another from the prehistoric and anthropological tradition. They look at the role of textual sources in reconstructing ethnicity and introduce fresh and innovative archaeological data, either from fieldwork or from new combinations of old data. Finally, in contrast to many traditional approaches to this subject, they examine the relative and interacting AREA MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAIC THE IN role of natural and cultural features in the landscape in the construction of ethnicity. The volume is headed by the contribution of Andrea Carandini whose work challenges the conceptions of many in the combination of text and archaeology. He begins by examining the mythology surrounding the founding of Rome, taking into consideration the recent archaeological evidence from the Palatine and the Forum. Here primacy is given to construction of place and mythological descent. Anthony Snodgrass, Robin Osborne, Tim Cornell and Christopher Smith offer replies to his arguments. Overall, the nineteen papers presented here show that a modern interdisciplinary and international archaeology that combines material data and textual evidence – critically – can provide a powerful lesson for the full understanding of the ideologies of ancient and modern societies G. G. C IFANI AND S. S TODDART EDITED BY ABRIELE IFANI AND IMON TODDART s G C S S Oxbow Books WITH THE SUPPORT OF SKYLAR NEIL www.oxbowbooks.com This pdf of your paper in Landscape, Ethnicity and Identity belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright.