Resource Productivity in the Irrigated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015-16 Term Loan

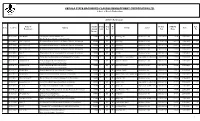

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kasaragod District from 15.10.2017 to 21.10.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Kasaragod district from 15.10.2017 to 21.10.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Nidheesh P Chandran 35/17 Perayil House, Kuttikole 15.10.201 Cr.No. BEDAKAM T Damodaran, BAILED Pilla Kuttikole, Kuttikole town, 7 483/17 u/s SI of Police, 1 village Kuttikole 118(a) of KP Bedakam PS village Act Anil K Krishnan 45/17 Manjanadukkam Manjanadukk 15.10.201 Cr.No. BEDAKAM T Damodaran, BAILED House, Kolathur am, Kolathur 7 484/17 u/s SI of Police, 2 village village 118(a) of KP Bedakam PS Act Jayaram P Parvathi 38/17 Karuna House, Manimoola, 16.10.201 Cr.No.485/17 BEDAKAM T Damodaran, BAILED Manimoola, Bandadka 7 u/s 279 IPC SI of Police, 3 Bandadka village village & sec 185 of Bedakam PS MV Act Muhammad Ahammad 33/17 Padupp, Choorithode, 18.10.201 Cr.No.486/17 BEDAKAM M J Abraham, BAILED Rafeeq N K Samad Shankarampady PO, Bandadka 7 u/s 4(1) r/w SI of Police, 4 Karivedakam village village 21(1) of Bedakam PS MMDR ACT Muhammad Aboobackar 32/17 Rahmath Manzil, Kundamkuzh 18.10.201 Cr.No.487/17 BEDAKAM M J Abraham, BAILED Shareef C M Kundamkuzhy, y, Bedakam 7 u/s 4(1) r/w SI of Police, 5 Bedakam village village 21(1) of Bedakam PS MMDR ACT Prasanth A T Appakunhi 28/17 Thaira House, Nellithavu, 19.10.201 Cr.No.488/17 BEDAKAM M J Abraham, BAILED Kuttikole, Kuttikole Kuttikole 7 u/s 279 IPC SI of Police, 6 village village & sec 185 of Bedakam PS MV Act Sivaprasad N Narayanan 20/17 Nerodi House, Bedakam PS 21.10.201 Cr.No. -

Allotment of Funds to Government Colleges 31-07-2018

- - - ----., PROCEEDINGS OF THE DIRECTOR OF COLLEGIATE E;DLTATIO~. THIRUV .~"\! ANTH__ APURA1vf Collegiate Education Depatiment :-J",;;v,, Initiatives - \Valk vvith a Scholar Programme 201 X-19 Allotment of fimds to Govemment Colleges- Orders issued. Order -:\o.P4 32224/2018/Coll.Edn Dated 31-07-2018 Read:- I. G 0 (Rt) No.1387/2018/H.Edn Dated 17-07-2018. 2. Request dated 24-07-2018 Received from Co-ordinator New Initiatives P··o... I_t &"nt"'111111"' c:. ORDER In the Govermnent order cited above Govenuneut han; accorckd Administrative Sanction for allotment of funds for conducting \valk vvith a Scholar programm.: during the Financial Y~?ar 2018-19. Sanction is hcrebv accorded to rekasc an amount ofRs.l6982500/- ~ J Rupc..:s One Crorc Si.\.iy Nine Lakhs Eighty T'>'m TI1ousand Five Hundred only) to,vards fimd for '"''~'S prot;ramme 20 18-19 Yvhich includes rupees 16781100 i_ (Rupees One Cron: Sixty ScYen Lakhs Eighty One Thousand One Hundred onl;) to 61 Govenuncnt Colkgcs (61 x 275100 ~= 16781100) and Rs. 20,1400/- ( Rupees Tvvo Lakhs One Thousand Four Hundred only) to 2 Government Colleges (2 x 100700 = 201 400). The List of GoYcmm~nt colleges \Yith allotted amount is attached. The principal concerned \\ill initiate necessary action to ensure complde utilization of funds by strictly obsaving the existing govenunent rules for utilization of plan funds, Stores purchase manual etc. Detailed guidelines \Yill be issued separately. The expenditure will be met from he head of Account 2202-03-105-95-wvv~ in the Current year's budget provision. Sd/- HAIUTHA. \'.Ke:MAR.IAS DIRECTOR OF COLLEGIATE EDCC.\TIO:\' Copy to:~ 1. -

Declaration of Results (Kannur University)

© Regn. No. KERBIL/2012/45073 tIcf k¿°m¿ dated 5-9-2012 with RNI Government of Kerala Reg. No. KL/TV(N)/634/2021-2023 2021 tIcf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[nImcnIambn {]kn≤s∏SpØp∂Xv PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY 2021 G{]n¬ 27 Xncph\¥]pcw, hmeyw 10 27th April 2021 \º¿ sNmΔ 1196 taSw 14 14th Medam 1196 17 Vol. X } Thiruvananthapuram, No. } 1943 sshimJw 7 Tuesday 7th Vaisakha 1943 PART IV Private Advertisements and Miscellaneous Notifications 27th APRIL 2021] KERALA GAZETTE 737 KANNUR UNIVERSITY (Election Cell) (1) No. KU/ELC2/AC-PRINCIPALS/2020. 13th Janaury 2021. Election of seven members (other than Deans of Faculties) of whom at least one shall be the Principal of a Government college, elected by the Principals of First Grade Colleges, other than colleges of Oriental languages, from among themselves, as per Section 26 (3)n of Kannur University Act, 1996 and Statute 39 (Chapter XLVI, part B) of Kannur University First Statutes, 1998. Declaration of Result In pursuance of Statute 39 of Chapter XLVI, ‘Elections’ (Part B) of Kannur University First Statutes 1998, the following Principals are declared elected from the constituency of ‘Principals of First Grade Colleges’ to the Academic Council of Kannur University. ER Name of the Address of the No. Candidate Candidate 4 Dr. Ajitha. V Mahathma Gandhi College, Iritty, P. O. Keezhur, Kannur-670 703 6 Dr. Maria Martin Joseph Mary Matha Arts & Science College, Vemom P. O., Mananthavady, Wayanad-670 645 14 Fr. Dr. Francis Karackat Don Bosco Arts and Science College, Angadikadavu P. O., Kannur-670 706 24 Dr. -

Name of District : KASARAGOD Phone Numbers LAC NO

Name of District : KASARAGOD Phone Numbers LAC NO. & PS Name of BLO in Name of Polling Station Designation Office address Contact Address Name No. charge office Residence Mobile "Abhayam", Kollampara P.O., Nileshwar (VIA), K.Venugopalan L.D.C Manjeshwar Block Panchayath 04998272673 9446652751 1 Manjeswar 1 Govt. Higher Secondary School Kunjathur (Northern Kasaragod District "Abhayam", Kollampara P.O., Nileshwar (VIA), K.Venugopalan L.D.C Manjeshwar Block Panchayath 04998272673 9446652752 1 Manjeswar 2 Govt. Higher Secondary School Kunjathur (Northern Kasaragod District N Ishwara A.V.A. Village Office Kunjathur 1 Manjeswar 3 Govt. Lower Primary School Kanwatheerthapadvu, Kun M.Subair L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Melethil House, Kodakkad P.O. 04998272673 9037738349 1 Manjeswar 4 Govt. Lower Primary School, Kunjathur (Northern S M.Subair L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Melethil House, Kodakkad P.O. 04998272673 9037738349 1 Manjeswar 5 Govt. Lower Primary School, Kunjathur (Southern Re Survey Superintendent Office Radhakrishnan B L.D.C. Ram Kunja, Near S.G.T. High School, Manjeshwar 9895045246 1 Manjeswar 6 Udyavara Bhagavathi A L P School Kanwatheertha Manjeshwar Arummal House, Trichambaram, Taliparamba P.O., Rajeevan K.C., U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath 04998272238 9605997928 1 Manjeswar 7 Govt. Muslim Lower Primary School Udyavarathotta Kannur Prashanth K U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath Udinur P.O., Udinur 04998272238 9495671349 1 Manjeswar 8 Govt. Upper Primary School Udyavaragudde (Eastern Prashanth K U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath Udinur P.O., Udinur 04998272238 9495671349 1 Manjeswar 9 Govt. Upper Primary School Udyavaragudde (Western Premkumar M L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Meethalveedu, P.O.Keekan, Via Pallikere 04998 272673 995615536 1 Manjeswar 10 Govt. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kasaragod District from 08.12.2019To14.12.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Kasaragod district from 08.12.2019to14.12.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 MATTA HOUSE 461/2019 U/s NOTICE NEAR MALIK KUMBLA 14-12-2019 279 SI MUHAMME 21, KUMBLA SERVED - 1 HAMEED DINAR MOSQUE POLICE at 17:00 IPC,132(1),19 SANTHOSH D UNAIS Male (Kasaragod) JFCM II ICHILANKOD STATION Hrs 4(D) r/w 177 KUMAR A Kasaragod VILLAGE of mv act Pernadukka House 14-12-2019 772/2019 U/s KASARGO Shiek Abdul Birma 55, Uliyathaduka, BAILED BY 2 Kotti Poojari RD Nagar Kudlu, at 20:05 118(i) of KP DE Razak,SI of Poojari Male kasaragod POLICE Kasaragod Hrs Act (Kasaragod) Police PADMANAB Thairavalappil 14-12-2019 MELPARA HAN M P, SI 34, PUTHARIYA 302/2019 U/s BAILED BY 3 Anilkumar A Krishnan TH House Thaira at 19:45 MBA OF POLICE, Male DUKKAM 15 of KG Act POLICE Thekkil village Hrs (Kasaragod) MELPARAM BA PS PADMANAB Kuthugudde 14-12-2019 MELPARA HAN M P, SI 33, PUTHARIYA 302/2019 U/s BAILED BY 4 Naveen K Ayyithan kakunje house at 19:45 MBA OF POLICE, Male DUKKAM 15 of KG Act POLICE neerchal Hrs (Kasaragod) MELPARAM BA PS Balamthodu,P 14-12-2019 251/2019 U/s RAJAPURA Shivakumar 30, Ariprode,panathady RAJEEVAN K BAILED BY 5 Gopalan anathady at 19:15 279 IPC & 185 M K G Male villege SI OF POLICE POLICE village Hrs MV ACT (Kasaragod) Sreelakshmi Nivas 14-12-2019 335/2019 U/s VELLERIKU ARRESTED - Jayaprakash. -

PG Courses Under Kannur University

ANNEXURE I Sl Name of the College Name of the Courses Total No seats* GOVERNMENT COLLEGES 1 GovindaPai Memorial M.Com.(Finance) 15 Government College, M.Sc. Statistics 14 Manjeswaram 2 Government College, M.A. Kannada 17 Kasaragod M.A. Economics 14 M.A. Arabic 14 M.A. English 15 M.Sc. Geology 14 M.Sc. Mathematics 15 M.Sc. Chemistry 16 3 E.K. Nayanar Memorial M.A. Applied Economics 21 Government College, Elerithattu, Kasaragod 4 K.M.M. Govt.Women’s M.A. English 20 College, Kannur M.A. Development Economics 18 5 Government Brennen M.A. History 20 College, Dharmadam, M.A. Malayalam 22 Thalassery M.A. Hindi 20 M.A. English 20 M.A. Economics 17 M.A. Philosophy 13 M.Sc. Mathematics 15 M.Sc. Physics 12 M.Sc. Botany 13 M.Sc. Zoology 13 M.Com. Finance 23 M.Sc. Chemistry 12 6 Govt. College M.Com.Finance 25 Mananthawady, M.A. English 20 P.O.Nalloornad, M.A. Development Economics 20 Mananthawady M.Sc Electronics 12 AIDED COLLEGES AIDED COLLEGES(BACKWARD MINORITY COMMUNITY) 1 N.A.M. College, Kallikandy, M.Com.Finance 25 Kannur MSc Computer Science (Unaided) 20 MA English (Unaided) 23 MSc Mathematics (Unaided) 23 2 Sir Syed College, MSc Botany. 17 Thaliparamba, Kannur. MSc Chemistry 17 MSc Physics 17 MA Arabic 14 17 MComFinance 23 3 SreeNarayana College, MA Economics 24 Thottada, Kannur MA English 15 MSc Zoology 14 MSc Chemistry 14 MSc Physics 14 MComFinance 22 AIDED COLLEGES(FORWARD MINORITY COMMUNITY) 1 Nirmalagiri College, M.A. Economics 15 Kuthuparamaba, Kannur M.Sc. -

Counting Posting

COUNTING POSTING - ASSEMBLY ALLOTTED DETAILS Supervisor COUNTING Supervisor ABDUL JALEEL K POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE Assistant Professor 4-KANHANGAD GOVT. COLLEGE, KASARAGOD, Vidyanagar P O, Kasaragod NEHRU ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE, 9995417121 Supervisor KANHANGAD ABDULLA T K POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE Senior Superintendent 5-TRIKARIPUR ASSISTANT EDUCATIONAL OFFICE, HOSDURG, Hosdurg, EKNM GOVT. POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE, 9497603367 Supervisor TRIKARIPUR ABDULLATHEEF N POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE HSST Senior Political Science 4-KANHANGAD CHMKSGVHSS, KOTTAPPURAM, \N NEHRU ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE, 9446748076 Supervisor KANHANGAD ABHILASH SOLOMON POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE Assistant Professor 5-TRIKARIPUR GOVT. COLLEGE, KASARAGOD, Vidyanagar P O, Kasaragod EKNM GOVT. POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE, 9074546866 Supervisor TRIKARIPUR ABHIRAM C P POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE HSST Computer Science 4-KANHANGAD S R M G H W H S RAMNAGAR, ANANDASRAM PO NEHRU ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE, 9447374841 Supervisor KANHANGAD AJAYAGHOSH M V POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE ASST. PROFESSOR 2-KASARAGOD G P M GOVT. COLLEGE, MANJESHWAR, MANJESHWAR PO, KASARA GOVT. COLLEGE , KASARAGOD 8086729564 Supervisor Ajayan S POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE Dairy Extension Officer 1-MANJESHWAR DAIRY EXTENSION SERVICE UNIT- MANJESHWARAM, Dairy extensi G H S S KUMBALA 9349977443 Supervisor AJAYKUMAR EYYAKKATT POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE HSST History 3-UDMA GHS Paivalike Nagar, Paivalike p.o GOVT. POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE, PERIYA 9349688877 Supervisor COUNTING POSTING - ASSEMBLY ALLOTTED DETAILS Supervisor AJEESH A POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE Assistant Professor (AGP 6000) 3-UDMA G P M GOVT. COLLEGE, MANJESHWAR, MANJESHWAR PO, KASARA GOVT. POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE, PERIYA 9422441007 Supervisor AJEESH P POSTED ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY AND COUNTING CENTRE Non Vocational Teacher 2-KASARAGOD C.H.M.K.S.G.V.H.S.S.KOTTAPURAM, KOTTAPURAM PO GOVT. -

B.A Political Science Programme at E.K.N.M Govt. College, Elerithattu

KANNUR ^&u*,rr*r,r, {Abstract) Provisional Attiliation - B.A. Political Science programme at E.K.N.M Gon. College, Elerithattu, Kasaragod for the academic year 2O2O-2O27- Granted - Orders issued. ACADEMIC A SECTION Acad.A3l7526l2O0O Dated: 03.06.2020 Read:-1. G.O (Ms) No.31/2020/HEdn dated 16.01-.2020. 2. Report of lnspection dated 05.03.2020. 3. Resolution of the Syndicate held on 10.03.2020 vide item no. 2020.1.80. 4. Letrer no. AUtO56l2072 dared 03.02.2020. 05.03.2020 & 20.03.2020 received from the Principal, EKNM Govt- College, Elerithattu. ORDER 1. As per the paper read (1) above, the Govt. of Kerala sanctioned B.A. Political Science programme at E.K.N.M Govt. College,Elerithattu,Kasaragod, ,or the academic year ?02O-202L. 2. Accordingly, an inspection was conducted in the College to verify the facilities for staning B.A.Political Science programme- The lnspection Commission vide the paper read (2) above verified the infrastructural and instructional facilities available in the college and found satislactory. The commission recommended to grant provisional affiliation to the B.A. Political Scaence programme, with an intake of 40 students during the academic yeat 2020-2021. 3. Subsequently,as per the paper read (3) above, the Syndicate resolved to approve the report ol the lnspection conducted at E.K.N.M Govt.College, Elerithattu, Kasaragod on 05.03.2020. 4.Thereafter,the Principal ol the College, vide the papers read (4)above, remitted the requisite fee and requested to grant Provisional Affiliation to the B.A. -

Kannur University

KANNUR UNIVERSITY Result Statistics - BA/BSW (CBCSS -2017 Admission) Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 3499 1925 55.02 8 233 804 766 113 1 ARABIC & ISLAMIC HISTORY Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 25 9 36 0 4 4 0 1 0 Govt. Brennen College, Thalassery 25 9 36 0 4 4 0 1 0 ARABIC Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 52 43 82.69 0 20 17 6 0 0 Govt College Kasargod,Kasargod 25 22 88 0 14 7 1 0 0 Sir Syed College, Thaliparamba 27 21 77.78 0 6 10 5 0 0 BHARATANATYAM Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 10 4 40 0 1 0 3 0 0 Lasya College of Fine Arts,Pilathara 10 4 40 0 1 0 3 0 0 DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 73 43 58.9 0 5 17 18 3 0 Govt College,Mananthavady 28 22 78.57 0 5 8 7 2 0 St. Pius X College, Rajapuram 45 21 46.67 0 0 9 11 1 0 ECONOMICS Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 642 351 54.67 2 48 174 116 11 0 E.K. Nayanar Memorial Govt. College, 34 20 58.82 0 2 9 9 0 0 Elerithattu,Nileshwar Govt. Brennen College, Thalassery 44 30 68.18 0 5 14 10 1 0 Govt College Kasargod,Kasargod 44 32 72.73 0 0 21 11 0 0 K.M.M Govt Women's College,Kannur 74 38 51.35 1 14 16 6 1 0 Malabar Islamic Complex Arts and Science 6 2 33.33 0 0 0 2 0 0 College, Thekkil Nehru Arts and Science College,Kanhangad 42 27 64.29 0 4 14 7 2 0 Nirmalagiri College,Koothuparamba 45 29 64.44 0 6 17 6 0 0 Naher Arts and Science College, Kanhirode 22 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Nalanda College of Arts and Science, Perla- 6 3 50 0 0 1 2 0 0 Kasaragod Peoples Co-operative Arts and Science 33 12 36.36 0 0 4 8 0 0 College,Munnad Payyannur College, Payyannur 55 31 56.36 1 4 16 7 3 0 Pazhassi Raja NSS College,Mattannur 52 28 53.85 0 6 14 8 0 0 St. -

Page Front 1-12.Pmd

REPORT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF KASARAGOD DISTRICT Dr. P. Prabakaran October, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page No. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 PART-I LAW AND ORDER *(Already submitted in July 2012) ............................................ 9 PART - II DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Development Sectors 2. Agriculture ................................................................................................................................................. 47 3. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development.................................................................................. 113 4. Fisheries and Harbour Engineering................................................................................................... 133 5. Industries, Enterprises and Skill Development...............................................................................179 6. Tourism .................................................................................................................................................. 225 Physical Infrastructure 7. Power .................................................................................................................................................. 243 8. Improvement of Roads and Bridges in the district and development -

Kannur University

KANNUR UNIVERSITY (Examination Branch) Result Statistics - B.Sc/ BCA (CBCSS -2018 Admission) April 2021 Examination Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 4070 2595 63.76 369 1125 838 255 8 0 BACHELOR OF COMPUTER APPLICATION Appeared Passed Percentage A+ A B C D E TOTAL 428 205 47.9 0 33 103 64 5 0 AMSTECK Arts and Science College, Kalliassery 7 5 71.43 003110 Chinmaya Arts and Science College for Women, 32 21 65.63 0 3 15 2 1 0 Chala Don Bosco Arts and Science College, 29 22 75.86 077800 Angadikadavu De Paul Arts and Science College, Edathotty 21 9 42.86 013500 Deva Matha Arts and Science College, Paisakari 11 7 63.64 003400 Sree Narayana Guru College of Advanced Studies, 30 10 33.33 005500 Thottada Gurudev Arts and Science College, Mathil 21 9 42.86 003600 Govt. College, Thalassery 23 12 52.17 038100 Green Woods Arts and Science College for 15 10 66.67 017200 Women, Palakkunnu ITM College of Arts and Science, Mayyil 28 13 46.43 035500 Concord Arts and Science College, Muttannur 14 7 50 005110 Morazha Co-op Arts and Science College, 26 15 57.69 046500 Morazha Navajyothi College, Cherupuzha 25 10 40 006400 Naher Arts and Science College, Kanhirode 8 00 000000 Our College of Applied Science ,Thimiri 3 00 000000 Pilathara Co-op Arts and Science College, 34 17 50 018800 Pilathara Sa-A-Diya Arts and Science College, 19 10 52.63 028000 Koliyadukkam St. Judes Arts & Science College, Vellarikundu 2 1 50 010000 S.E.S College, Sreekandapuram 10 2 20 020000 SIBGA Institute of Advanced Studies, Irikkur 12 4 33.33 002110 St.