Antisemitism on Campus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Prime Minister's Holocaust Commission Report

Britain’s Promise to Remember The Prime Minister’s Holocaust Commission Report Britain’s Promise to Remember The Prime Minister’s Holocaust Commission Report January 2015 2 Britain’s Promise to Remember The Prime Minister’s Holocaust Commission Report Front cover image: Copyright John McAslan and Partners © Crown copyright 2015 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence, write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. This publication is available from www.gov.uk Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to: Cabinet Office 70 Whitehall London SW1A 2AS Tel: 020 7276 1234 If you require this publication in an alternative format, email [email protected] or call 020 7276 1234. Contents 3 CONTENTS Foreword 5 Executive Summary 9 Introduction 19 Holocaust Education and Commemoration Today 25 Findings 33 Recommendations 41 Delivery and Next Steps 53 Appendix A Commissioners and Expert Group Members 61 Appendix B Acknowledgements 62 4 Prime Minister’s Holocaust Commission – Summary of evidence Foreword 5 FOREWORD At the first meeting of the Holocaust Commission exactly one year ago, the Prime Minister, David Cameron, set out the task for the Commission. In response, one of my fellow Commissioners, Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, noted that the work of this Commission was a sacred duty to the memory of both victims and survivors of the Holocaust. One year on, having concluded its work in presenting this report, I believe that the Commission has fulfilled that duty and has provided a set of recommendations which will give effect to an appropriate and compelling memorial to the victims of the Holocaust and to all of those who were persecuted by the Nazis. -

Antisemitism

Government Action on Antisemitism December 2014 Department for Communities and Local Government © Crown copyright, 2014 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence,http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. This document/publication is also available on our website at www.gov.uk/dclg If you have any enquiries regarding this document/publication, complete the form at http://forms.communities.gov.uk/ or write to us at: Department for Communities and Local Government Fry Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Telephone: 030 3444 0000 For all our latest news and updates follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/CommunitiesUK December 2014 ISBN: 978-1-4098-4445-7 Contents Summary of key achievements 4 Introduction 6 Theme 1- Antisemitic Incidents 10 Theme 2 – Antisemitic Discourse 16 Theme 3 – Sources of Contemporary antisemitism 17 Theme 4 - Antisemitism on campus 23 Theme 5 – Addressing antisemitism 26 Summary of the response to the APPG Against Antisemitism Inquiry (2006) recommendations 36 3 Summary of key achievements • DCLG continues to support the work of the Cross Government Working Group on addressing antisemitism. • Government has worked with the Inter-Parliamentary Coalition for Combatting Antisemitism’s efforts to work constructively with technology and social media companies to set effective protocols for addressing harm. -

2018 Table of Contents

INSIDE OUR GRANTS 2017-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................... 2 What’s in This Book? ............................................................................................ 3 Jewish Communal Network ................................................................................... 5 Overview ............................................................................................................. 6 Membership List ...................................................................................................7 Fiscal 2018 Grants .................................................................................................8 Jewish Life ..........................................................................................................15 Overview ............................................................................................................ 16 Membership List ................................................................................................. 17 Fiscal 2018 Grants ............................................................................................... 18 Caring ................................................................................................................ 29 Overview ............................................................................................................30 Membership List ................................................................................................ -

Israel in the Synagogue Dr. Samuel Heilman, Professor of Jewish Studies and Sociology, City University of New York

Israel in the Synagogue Dr. Samuel Heilman, Professor of Jewish Studies and Sociology, City University of New York Israel in Our Lives is a project sponsored by The CRB Foundation, The Joint Authority for Jewish Zionist Education Department of Jewish Education and Culture in the Diaspora, and The Charles R. Bronfman Centre for the Israel Experience: Mifgashim. In cooperation with Jewish Education Service of North America and Israel Experience, Inc. Israel In Our Lives Online was funded in part through a generous grant from the Joint Program for Jewish Education of the Jewish Agency for Israel and the Ministry of Education and Culture of the State of Israel. The editors would like to thank all the authors, advisors, and consultants of the Israel In Our Lives series— educational leaders who have brought their considerable insights and talents to bear on this project. In addition to those already mentioned in these pages, we extend our appreciation to those who helped in shaping the project concept: Dr. Zvi Bekerman, Gidon Elad, Dr. Cecile Jordan, Rachel Korazim, Clive Lessem, Caren Levine, Dr. Zev Mankowitz, Dr. Eliezer Marcus, & Susan Rodenstein. Part 1 While no one would suggest that the synagogue and Israel are duplicates of one another - and indeed the differences between them are legion - they have in this generation increasingly represented (especially for North American Jewry) two important, parallel symbols of Jewish identity. This is because both are special "places" in which being a Jew constitutes an essential pre-requisite, perhaps even a sine qua non, for affiliation. Additionally, both are places where one expects to find Jews in the overwhelming majority and in charge, where Jewish concerns are paramount, and where Hebrew is spoken. -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain* JLHE PERIOD under review (July 1, 1962, to December 31, 1963) was an eventful one in British political and economic life. Economic recession and an exceptionally severe winter raised the number of unemployed in Jan- uary 1963 to over 800,000, the highest figure since 1939. In the same month negotiations for British entry into the European Common Market broke down, principally because of the hostile attitude of President Charles de Gaulle of France. Official opinion had stressed the economic advantages of union, but enthusiasm for the idea had never been widespread, and there was little disappointment. In fact, industrial activity rallied sharply as the year progressed. In March 1963 Britain agreed to the dissolution of the Federation of Rho- desia and Nyasaland, which had become inevitable as a result of the transfer of power in Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia to predominantly African governments and the victory of white supremacists in the elections in South- ern Rhodesia, where the European minority still retained power. Local elections in May showed a big swing to Labor, as did a series of par- liamentary by-elections. A political scandal broke out in June, when Secretary for War John Pro- fumo resigned after confessing that he had lied to the House of Commons concerning his relations with a prostitute, Christine Keeler. A mass of infor- mation soon emerged about the London demimonde, centering on Stephen Ward, an osteopath, society portrait painter, and procurer. His sensational trial and suicide in August 1963 were reported in detail in the British press. A report issued in September by Lord Denning (one of the Law Lords) on the security aspects of the scandal disposed of some of the wilder rumors of immorality in high places but showed clearly the failure of the government to deal with the problem of a concurrent liaison between the war minister's mistress and a Soviet naval attache. -

Ageing Well Within the Jewish Community in the 21St Century Contents

An agenda for ageing well within the Jewish Community in the 21st century Contents 01 An Introduction 03 Executive Summary 05 A Blessing: A Jewish Perspective 06 Putting the Agenda in context 08 1. Spritual and Emotional Wellbeing 10 2. Intellectual and Life-long Learning 12 3. Active Participation & Connection 14 4. Independence and Healthy Living 16 5. Care 18 Next Steps 19 Acknowledgements 20 Action Plan 21 Glossary of Terms An Introduction The Torah considers growing The Background old a blessing; ‘zakein’ (old) is synonymous with wise. • The Jewish community has twice the number of people over 60 Our heroes and heroines compared to the general UK population. Yet most of our resources – were not young – Abraham, energy and money – are directed towards young people. • The Jewish community does welfare well. Sarah, Moses. It would • But growing old is not just about welfare. benefit us all if the Jewish • This report consulted with over 500 people representing a cross community began to section of the Jewish community. challenge youth obsessed • This report is not about being old; it’s about ageing – which we are all doing. culture. The Key Recommendations • The Jewish community should ensure that, as we age, we are enabled and encouraged to flourish and participate to the best of our physical and mental abilities. • The emphasis should change from welfare to inclusion. • Communal organisations should change to ensure they actively include older people. • The community needs to focus on this important and growing area. • The community needs to listen to what people are saying rather than deciding what they want and need. -

Berlin Conference Agenda 2014-NOVEMBER 12 and 13 FINAL II

10 TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE OSCE’S BERLIN CONFERENCE ON ANTI-SEMITISM HIGH-LEVEL COMMEMORATIVE EVENT AND CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM 12-13 November 2014 Weltsaal, Federal Foreign Office, Berlin AGENDA 12 NOVEMBER 2014 – CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM ON ANTI-SEMITISM 09:00 – 09:30 OPENING SESSION Welcome Remarks: Felix Klein , Ambassador, Special Representative for Relations with Jewish Organisations, Federal Foreign Office, Germany Heidi Grau , Ambassador, Head of the OSCE Chairmanship Task Force, Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs Rabbi Andrew Baker , Personal Representative of the OSCE Chairperson-in-Office on Combating Anti-Semitism Cristina M. Finch , Head, Tolerance and Non-Discrimination Department, OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights 09:30 – 11:00 PLENARY SESSION Panellist s: Dániel Bodnár , Chariman of the Board, Action and Protection Foundation, Hungary Ilja Sichrovsky , Founder and Secretary-General, Muslim-Jewish Conference (MJC) Jane Braden-Golay , President, European Union of Jewish Students (EUJS) Hanne Thoma , Coordinator, Task Force Education on Antisemitism, Germany Karen Polak , Project Manager, Anne Frank House, Netherlands Vitalii Bobrov , Coordinator of Educational Programs, Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies 2 Moderators: Deidre Berger , Director, American Jewish Committee (AJC) Berlin Ramer Institute for German-Jewish Relations, United States of America Juliane Wetzel , Senior Researcher and Senior Staff Member, Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technical University Berlin, Germany 11:00 – 11:30 -

The Jewish Manifesto the Board of Deputies of British Jews Is the Democratic and Representative Body for the UK’S Jewish Community

THE JEWISH MANIFESTO The Board of Deputies of British Jews is the democratic and representative body for the UK’s Jewish community. We are the first port of call for Government, the media and others seeking to understand the Jewish community’s interests and concerns. The Board of Deputies acts as the Secretariat to the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on British Jews. The APPG aims to broaden and deepen connections between Parliament and the UK’s Jewish community. Charitable activities with which the Board of Deputies is identified are funded by The Board of Deputies Charitable Foundation (Registered Charity No. 1058107), a company limited by guarantee and registered in England (No. 3239086). Copyright © 2019 The Board of Deputies of British Jews Printed in the United Kingdom THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________ 3 THE TEN COMMITMENTS __________________________________________ 4 GLOBAL JEWISH ISSUES 6 ANTISEMITISM ___________________________________________________ 7 RACISM _________________________________________________________ 8 EXTREMISM _____________________________________________________ 9 COMMUNITY RELATIONS ________________________________________ 12 RELIGIOUS FREEDOM ____________________________________________ 12 HOLOCAUST ISSUES ____________________________________________ 16 ISRAEL AND THE MIDDLE EAST ___________________________________ 19 BREXIT _________________________________________________________ 24 JEWISH LIFE CYCLE 26 EDUCATION ____________________________________________________ -

UJS Conference 2020 Motions

UJS Conference 2020 Motions Campus Motion Title: CA3 Fighting Antisemitism with the Jewish Labour Movement Proposer’s name: Jack Lubner Proposer’s J-Soc: Cambridge Seconder’s name: Toby Kunin Seconder’s J-Soc: Warwick What’s the idea? 1. The issue of antisemitism in the Labour Party has been incredibly difficult for the Jewish community and for Jewish students in particular, who have faced antisemitism on campus. 2. The Labour Party’s new leadership have made promising steps in dealing with the problem of antisemitism in Labour but there is still a long way to go. 3. The Jewish Labour Movement (JLM) played a key role in the fight against antisemitism, having referred the Labour Party to the Equalities and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) – which found it guilty of committing three unlawful acts. 4. UJS has worked with JLM in the past to provide antisemitism awareness training on campus. How do you want it to happen? 1. UJS should continue to work alongside the Jewish Labour Movement in co-hosting events to share the experiences of Jewish students. 2. If antisemitism awareness training in University Labour Clubs resumes, UJS should facilitate training with JLM. UJS should be in regular contact with JLM to coordinate efforts to fight antisemitism on campus when it arises in Labour Party spaces. Motion Title: CA6 Committing to Fight All Forms of Antisemitism Proposer’s name: Millie Walker Proposer’s J-Soc: Leeds Seconder’s name: Tamar Klajman Seconder’s J-Soc: UCL What’s the idea? 1. Antisemitism is rising at an alarming rate at universities across the world. -

2015 Report Welcome to Mitzvah Day 2015 Dan Rickman

Mitzvah Day 2015 Report Welcome to Mitzvah Day 2015 Dan Rickman As the recently appointed Director of Mitzvah Day it is my absolute pleasure to launch the new look and feel of Mitzvah Day 2016, which this year will take place on 27th November. It’s hard to think of a time when we Mitzvah Day is expanding and didn’t see the Mitzvah Day green becoming an even greater force for t-shirts come out in force every good. We ran 550 Mitzvah Days in November, and yet it’s easy to forget 21 countries in 2015 and we’ve seen that Mitzvah Day is only eight years growth in our essential interfaith work, old. Our challenge is to ensure that and our project which engages young Jewish led Mitzvah Day continues to adults. Our Mitzvah Day Together evolve and make an impact on as many programme supports disabled people volunteers and charities as possible. to participate in volunteering, and we have continued to work with non- So much work goes into making sure Jewish schools and offices. Mitzvah Day happens. This year we have focused on making sure we deliver the This report gives you the opportunity most efficient Mitzvah Day ever. to reflect on what we have achieved in 2015, and for us to showcase how we Our new website and database will plan to grow in 2016 and beyond. make it easier than ever to register as a partner, and to find and participate We look forward to seeing you on in a Mitzvah Day project. -

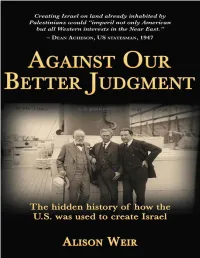

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

2020 Grants Book

REPORT OF GRANTS AWARDED 2019-2020 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 What We Do — And How We Do It 2 Where Our Dollars Go 3 Fiscal Year 2020 Grants by Agency: Full Listing 4 Named Endowments and Spending Funds 40 2020 Leadership List 46 4 INTRODUCTION A YEAR LIKE NO OTHER In a typical year, this grants book would be an important record of our shared investments in our community. The year 2020 has been anything but typical. While this report still documents our collective grant making, reflecting our commitment to the highest degree of programmatic integrity and true fiscal transparency, it is also a testament to the heroic efforts that have kept critical services and mission-driven programs going despite a global pandemic. For so many individuals, day-to-day life is a regular series of obstacles and uncertainties. Multiply that by millions of people impacted by Covid-19, and you have some sense of what has been required to assure that we are remaining true to UJA-Federation’s mission to care, connect, and inspire. So, while this is a report of our annual accomplishment, it is also a tribute to the unwavering determination of professionals and volunteers within UJA, at agencies and in neighborhoods, on front lines and on screens, who have simply refused to allow a novel virus to alter decades-old commitments in New York, in Israel, and around the world. This fortitude required stunning acts of generosity. We continue to honor the system created by UJA’s founders that not only has stood the test of time but continues to shape the future of our collective story.