Health Innovation Manchester: Origins, Formalization, Operation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CMFT/UHSM Phase 1 Decision, Paragraph 52

A report on the anticipated merger between Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust Appendices and glossary Appendix A: Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Appendix B: Industry background and regulation in the NHS Appendix C: Analytical method and detailed analysis of NHS elective and maternity specialties Appendix D: Past service improvement initiatives involving CMFT and UHSM Glossary Appendix A: Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Terms of reference 1. On 27 February 2017, the CMA referred the anticipated merger between Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust for an in- depth phase 2 investigation: 1. In exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act) the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that: (a) arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation, in that: (i) enterprises carried on by Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust will cease to be distinct from enterprises carried on by University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust; and (ii) the condition specified in section 23(1)(b) of the Act is satisfied; and (b) the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within a market or markets in the United Kingdom for goods or services, including the supply of several acute elective specialties and maternity services. -

2021/22 Annual Plan

Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust 2021/22 Annual Plan 1 | P a g e CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 6 2. MFT - Who we are 7 3. MFT Planning Framework 8 Internal ▪ Our Vision 8 ▪ Our Values 9 ▪ Our Clinical Service Strategies 10 ▪ Our Recovery Principles 11 External ▪ NHS E/I Priorities for 2021/22 12 ▪ GM Health & Social Care System Priorities 13 4. MFT Priorities for 2021/22 14 ▪ To improve patient safety, clinical quality and 15 outcomes ▪ To improve the experience of patients, carers and 18 their families ▪ To develop our workforce enabling each member 20 of staff to reach their full potential ▪ To develop single services that build on the best 22 from across all our hospitals ▪ To develop our research portfolio and deliver 23 cutting edge care to patients ▪ To complete the creation of a Single Hospital 25 Service for Manchester/ MFT with minimal disruption whilst ensuring that the planned benefits are realised in a timely manner ▪ To achieve financial sustainability 26 5. Risk and Monitoring Arrangements 30 2 | P a g e Glossary of Abbreviations AOF Accountability Oversight Framework ARC-GM Applied Research Collaboration Greater Manchester ATMP Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products BAU Business as Usual DoN Director of Nursing CDSU Clinical Data Science Unit CHD Community Diagnostic Hub CQC Care Quality Commission CYP Children & Young People DH Department of Health DHSC Department of Health and Social Care DiTA Diagnostics and Technology Accelerator ED Emergency Department EPR Electronic Patient Record E&T Education & Training FBC -

Patient Benefits Submission to the Competition & Markets Authority

Patient Benefits Submission to the Competition & Markets Authority Anticipated merger Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust Contents 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 6 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 12 3. Merger rationale and transaction process .............................................................................. 13 3.1 Events leading to the decision to create a single acute trust for Manchester ........... 13 3.2 Merger rationale ................................................................................................................. 14 3.2.1 Improving services: the Single Hospital Service review ....................................... 15 3.2.2 Organisational barriers to service improvement efforts ........................................ 17 3.3 Wider benefits expected from the merger ...................................................................... 20 3.4 Transaction governance and process ............................................................................. 21 4. Patient benefits overview .......................................................................................................... 22 4.1 Clinical engagement and the development of patient benefits ................................... 22 -

Final Report

Final Report regarding A New Health Deal for Trafford provided by DR JANELLE YORKE Independent Analyst on 28th November 2012 at the request of NHS Trafford 2nd Floor Oakland House Talbot Road Old Trafford Manchester M16 0PQ J Yorke, PhD, MRes, Independent Analyst Contents page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 3 DEMOGRAPHIC SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 5 Demographic summary for the consultation response form ............................................................................... 5 Demographic summary for the responses received through community focus groups and letters .................... 7 RESPONSES TO EACH ITEM ....................................................................................................................... 9 Question 1: Our vision for integrated care .......................................................................................................... 9 Question 2: The reason for change .................................................................................................................... 15 Question 3: The proposal ................................................................................................................................... 22 a) Orthopaedics ............................................................................................................................................ -

This Is a Replacement Post for Current Incumbent, Mr. Mazhar Iqbal Who Has Secured a Post for Family Reasons Closer to His Home in North Wales

JOB DESCRIPTION CONSULTANT IN ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY WITH SPECIAL INTEREST IN ONCOLOGY & RECONSTRUCTION This is a replacement post for current incumbent, Mr. Mazhar Iqbal who has secured a post for family reasons closer to his home in North Wales. The post will become vacant from mid-October 2020. Currently the post is based at Wythenshawe hospitals with additional clinical sessions at Stepping Hill Hospital, Stockport and MDT and Clinic at the Christie Hospital, Manchester. Maxillofacial Surgery and Head and Neck Oncological services in Manchester are undergoing re-organization/transformation into a single operational site. The post holder will be expected to accommodate their sessions to fit into the new service. The employing Trust is Manchester Foundation Trust (MFT) Vision The vision of Manchester University Foundation Trust (formerly CMFT & UHSM) is to be recognised internationally as leading healthcare; excelling in quality, safety, patient experience, research, innovation, and teaching; dedicated to improving health and well-being for our diverse population. Our Values Open and Honest Dignity in Care Working Together Everyone Matters Profile Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT is a major teaching Trust with nine hospitals. The hospitals are Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI), Manchester Royal Eye Hospital (MREH), St Marys Hospital (SMH), and Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital (RMCH) all at the main Central Manchester site, the University Dental Hospital and Trafford General Hospital (TGH) and Wythenshawe Hospital, -

Strategic Plan 2014/15 - 2018/19 Public Version

Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust STRATEGIC PLAN 2014/15 - 2018/19 PUBLIC VERSION CONTENTS Page 1 DECLARATION OF SUSTAINABILITY 3 PLAN-ON-A-PAGE 2 CMFT PROFILE 6 3 CONTEXT 12 Health Economy 12 Health Needs/Demography 16 Capacity 17 Alignment Across LHE 19 4 STRATEGIC PLANS 20 Specialised Services Strategy 20 Healthier Together 21 Living Longer, Living Better 22 Research & Innovation and Technology Strategy 23 2 Declaration of Sustainability of Declaration 1. DECLARATION OF SUSTAINABILITY Since 1752 when the MRI first opened in Manchester city centre, this Trust has been an important landmark on the healthcare landscape locally and nationally. We have a strong track-record of delivering excellent clinical outcomes, delivering NHS performance targets and achieving financial balance. Over the last 3 years we have improved our HSMR and SHMI year on year, achieved a governance risk rating of amber-green or above and maintained a Financial Risk Rating of 3 or above. We do however recognise the scale of the challenges facing us going forward. The most significant of these include ensuring that we build on the unique strengths of the Trust to deliver world-class services and ground-breaking research that will benefit patients, playing our part in addressing the poor health outcomes and health inequalities in Central and Greater Manchester and delivering all of this through limited overall NHS resources. We are pursuing a number of strategic initiatives that will enable us to remain clinically and financially viable -

CMFT/UHSM: Phase 1 Submission

Submission to the Competition & Markets Authority Anticipated merger Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 3 2. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 6 3. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE FOR THE PLANNED MERGER.................................. 7 3.1 Healthcare services in Greater Manchester ..................................................................... 8 3.2 Devolution of health and social care to Greater Manchester ...................................... 16 3.3 City of Manchester Single Hospital Service review....................................................... 19 4. COUNTERFACTUAL ................................................................................................................. 22 4.1 Single contract for acute services in Manchester .......................................................... 23 4.2 UHSM’s ability to compete with CMFT ........................................................................... 23 4.3 Service reconfiguration plans for Greater Manchester ................................................. 24 5. ROLE OF COMPETITION IN INFLUENCING THE PROVISION OF NHS ACUTE SERVICES ......................................................................................................................................... -

Newsletter Young People's Event 260618

Special Edition Summer 2018 Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital University Dental Hospital of Manchester Manchester Royal Eye Hospital Manchester Royal Infirmary Foundation Withington Community Hospital Wythenshawe Hospital Trafford General Hospital Saint Mary’s Hospital Focus Newsflash Altrincham Hospital Community Services Come and find out about careers in the NHS – and staying healthy! As an NHS Foundation Trust, we are committed to engaging with both our members and the public. We try to achieve this in many ways, including through regular membership events such as our Annual Members’ Meeting and our Young People’s Event. Our Young People’s Event was created as a result of discussions and feedback from young people and it continues to go from strength to strength. Our event this year will be our ninth and we hope that it will be just as successful. Over the years, more than 3,000 young people with their teachers, friends or parents have attended and gained an insight into our organisation. It’s also an opportunity to discover more about NHS careers, Volunteering, Work Experience and Youth Forum opportunities and how you can become more involved in our Foundation Trust by becoming a member (if aged 11 years or over). As an NHS Foundation Trust with a large Children’s Hospital, we are committed to ensuring that young people have a way to express their views. We therefore have a Youth Governor on our Council of Governors. Our Governors (elected representatives for members and the public) will be available throughout the event to talk about their role and the benefits of being anNHS Foundation Trust Member. -

Trust Trust Site Post Code NHS Region BEDFORDSHIRE HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST BEDFORD HOSPITAL SOUTH WING MK42 9DJ East of E

Trust Trust Site Post code NHS region BEDFORDSHIRE HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST BEDFORD HOSPITAL SOUTH WING MK42 9DJ East of England BEDFORDSHIRE HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST HARPENDEN MEMORIAL HOSPITAL AL5 4TA East of England BEDFORDSHIRE HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST LUTON & DUNSTABLE HOSPITAL LU4 0DZ East of England CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST ADDENBROOKE'S HOSPITAL CB2 0QQ East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE AND PETERBOROUGH NHS FOUNDATION TRUST FULBOURN HOSPITAL CB21 5EF East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE AND PETERBOROUGH NHS FOUNDATION TRUST HINCHINGBROOKE HOSPITAL PE29 6NT East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE AND PETERBOROUGH NHS FOUNDATION TRUST NEWTOWN CENTRE PE29 3RJ East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE COMMUNITY SERVICES NHS TRUST CCS NHS TRUST HEAD OFFICE PE27 4LG East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE COMMUNITY SERVICES NHS TRUST DODDINGTON HOSPITAL PE15 0UG East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE COMMUNITY SERVICES NHS TRUST NORTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE HOSPITAL PE13 3AB East of England CAMBRIDGESHIRE COMMUNITY SERVICES NHS TRUST OAK TREE CENTRE PE29 7HN East of England EAST AND NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE NHS TRUST LISTER HOSPITAL SG1 4AB East of England EAST COAST COMMUNITY HEALTHCARE C.I.C ECCH BECCLES HOSPITAL NR34 9NQ East of England EAST OF ENGLAND AMBULANCE SERVICE NHS TRUST BEDFORD LOCALITY OFFICE MK41 0RG East of England EAST OF ENGLAND AMBULANCE SERVICE NHS TRUST LETCHWORTH AMBULANCE STATION SG6 2AZ East of England EAST OF ENGLAND AMBULANCE SERVICE NHS TRUST Melbourn - HART OFFICE SG8 6NA East of England EAST SUFFOLK AND NORTH ESSEX NHS -

A Report Looking Into the Public Perception of Trafford General Hospital

A report looking into the public perception of Trafford General Hospital May to June 2019 Published October 2019 Introduction to Healthwatch Trafford ............................................................... 2 Executive summary..................................................................................... 3 Key findings: .......................................................................................... 3 Questions and Recommendations .................................................................... 4 Background .............................................................................................. 6 Methodology ............................................................................................. 7 Data collection ....................................................................................... 7 Analysis of data ...................................................................................... 7 Points to note ........................................................................................... 8 Results ................................................................................................... 9 Q1. Which of the following services do you think Trafford General Hospital provides? ... 9 Q2. Trafford General Hospital has an Urgent Care Centre. Do you know what the difference is between this and an Accident and Emergency (A&E) department? ......... 11 Q3. Do you know what specialisms that Trafford General Hospital has? (That is, services that Trafford General Hospital are specialists -

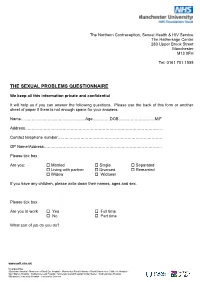

The Sexual Problems Questionnaire

The Northern Contraception, Sexual Health & HIV Service The Hathersage Centre 280 Upper Brook Street Manchester M13 0FH Tel: 0161 701 1555 THE SEXUAL PROBLEMS QUESTIONNAIRE We keep all this information private and confidential It will help us if you can answer the following questions. Please use the back of this form or another sheet of paper if there is not enough space for your answers. Name…………………………………………Age………….DOB………………………M/F Address………………………………………………………………………………………… Contact telephone number…………………………………………………………………… GP Name/Address……………………………………………………………………………. Please tick box Are you: Married Single Separated Living with partner Divorced Remarried Widow Widower If you have any children, please write down their names, ages and sex. Please tick box Are you in work Yes Full time No Part time What sort of job do you do? www.mft.nhs.uk Incorporating: Altrincham Hospital • Manchester Royal Eye Hospital • Manchester Royal Infirmary • Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital • Saint Mary’s Hospital • Trafford General Hospital • University Dental Hospital of Manchester • Wythenshawe Hospital • Withington Community Hospital • Community Services PAST HISTORY How would you describe the quality of your relationship within your family while growing up? Relationship with mother: Relationship with father: Relationship with brothers / sisters Do you remember any particular happy or unhappy times or events in your childhood / adolescence? Please say something about your past sexual experiences and relationships. www.mft.nhs.uk Incorporating: Altrincham Hospital • Manchester Royal Eye Hospital • Manchester Royal Infirmary • Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital • Saint Mary’s Hospital • Trafford General Hospital • University Dental Hospital of Manchester • Wythenshawe Hospital • Withington Community Hospital • Community Services GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Are you currently on any prescribed medication? YES/NO If yes please give details 2. -

Become a Member of Our NHS Foundation Trust

Become a Member of our NHS Foundation Trust We believe that good health services are vital to every local community and that our hospitals provide a modern, dependable, first-class healthcare service to the residents of Manchester, Trafford, Greater Manchester, and the North West that we can all be proud of. Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital Altrincham Hospital Manchester Royal Infirmary Wythenshawe Hospital University Dental Hospital of Manchester The Boulevard - Oxford Road Campus Manchester Royal Eye Hospital Saint Mary’s Hospital Withington Community Hospital Trafford General Hospital Benefits of being a Foundation Trust As a Foundation Trust we are directly accountable to our members, local population/communities, partners and other organisations with whom we work. As a Member of our Trust, you would have a very real opportunity, through your elected representatives (Governors), to shape our future and ensure services are developed that best meet your and your family’s needs. As a Trust with a large Children’s Hospital, we are conscious that young people need a way to articulate their views and we have developed our relationship with the Trust’s Youth Forum to ensure that young people are represented on our Council of Governors. Benefits of being a Foundation Trust Member Membership is completely free and is open to anyone who lives in England and Wales who is aged 11 years or over. Once a Member, you can choose how much you want to be involved. For example, you may just want to vote for representatives (Governors) during the election process and receive regular and exclusive membership information (newsletters and updates).