The Voting Rights Act and the Election of Nonwhite Officials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Women and the Presidency

Women and the Presidency By Cynthia Richie Terrell* I. Introduction As six women entered the field of Democratic presidential candidates in 2019, the political media rushed to declare 2020 a new “year of the woman.” In the Washington Post, one political commentator proclaimed that “2020 may be historic for women in more ways than one”1 given that four of these woman presidential candidates were already holding a U.S. Senate seat. A writer for Vox similarly hailed the “unprecedented range of solid women” seeking the nomination and urged Democrats to nominate one of them.2 Politico ran a piece definitively declaring that “2020 will be the year of the woman” and went on to suggest that the “Democratic primary landscape looks to be tilted to another woman presidential nominee.”3 The excited tone projected by the media carried an air of inevitability: after Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, despite receiving 2.8 million more popular votes than her opponent, ever more women were running for the presidency. There is a reason, however, why historical inevitably has not yet been realized. Although Americans have selected a president 58 times, a man has won every one of these contests. Before 2019, a major party’s presidential debates had never featured more than one woman. Progress toward gender balance in politics has moved at a glacial pace. In 1937, seventeen years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Gallup conducted a poll in which Americans were asked whether they would support a woman for president “if she were qualified in every other respect?”4 * Cynthia Richie Terrell is the founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s representation and leadership in the United States. -

Patsy Mink by D

LESSON 4 TEACHER’S GUIDE Patsy Mink by D. Jeanne Glaser Fountas-Pinnell Level W Narrative Nonfiction Selection Summary Pasty Mink experienced discrimination as a young woman, but she was determined to achieve her goals. She worked tirelessly to make sure that women in future generations had equal opportunities. Number of Words: 2,494 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Narrative nonfi ction, biography Text Structure • Third-person narrative in twelve short chapters • Chapter headings signal key periods in Patsy’s life and Title IX Content • Discrimination against women and immigrants • Passage of a bill in the United States Congress Themes and Ideas • Belief in oneself and determination can help overcome discrimination. • Everyone deserves equal opportunities. • People can initiate and make change. Language and • Conversational language Literary Features • Little fi gurative language—sprang into action Sentence Complexity • A mix of short and complex sentences • Complex sentences—phrases, clauses, compounds Vocabulary • New vocabulary words: instrumental, discrimination, emigrated • Words related to government and law: Title IX, debate, legislator, bill, repealed, lobby Words • Many multisyllable words: qualifying, intimidated, controversial Illustrations • Black-and-white/color photographs, some with captions Book and Print Features • Sixteen pages of text with chapter headings and photographs • Table of contents lists chapters headings • Text boxes highlight content • Timeline and diagram summarize content © 2006. Fountas, I.C. & Pinnell, G.S. Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. -

Congressional Record—Senate S6471

October 25, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6471 Unfortunately, we are now at a point I yield back my time. ances, they did not envision a sham where this program has been tapped The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Sen- confirmation process for judicial nomi- out. Why? Because the $44 billion that ator from Delaware. nees. But as much as I hate to say it, was set aside in the Disaster Relief NOMINATION OF AMY CONEY BARRETT that is what this one has been, pure Fund is gone, leaving $25 billion to deal Mr. CARPER. Mr. President, I rise and simple. This entire process has be- with natural disasters, which is what this afternoon to share with you and come an exercise in raw political the Disaster Relief Fund is intended to our colleagues some of my thoughts power, not the deliberative, non- do. And they need that money. We concerning the nomination of Judge partisan process that our Founders en- shouldn’t use any more of that. So we Amy Coney Barrett to serve as an As- visioned. are back to square one. sociate Justice of the Supreme Court of Frankly, it has been a process that I People who have had unemployment these United States. could never have imagined 20 years ago insurance since the disaster began be- I believe it was Winston Churchill when I was first elected to serve with cause they might work in hospitality, who once said these words: ‘‘The fur- my colleagues here. Over those 20 entertainment, travel, some businesses ther back we look, the further forward years, I have risen on six previous oc- where they can’t go back—a lot of we see.’’ So let me begin today by look- casions to offer remarks regarding those folks now are seeing just a State ing back in time—way back in time. -

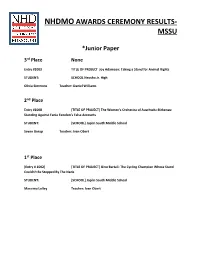

MSSU Results

NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Paper 3rd Place None Entry #1003 TITLE OF PROJECT Joy Adamson: Taking a Stand for Animal Rights STUDENT: SCHOOL Neosho Jr. High Olivia Simmons Teacher: Daniel Williams 2nd Place Entry #1008 [TITLE OF PROJECT] The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz-Birkenau: Standing Against Fania Fenelon’s False Accounts STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School Seven Borup Teacher: Ivan Obert 1st Place [Entry # 1002] [TITLE OF PROJECT] Gino Bartali: The Cycling Champion Whose Stand Couldn't Be Stopped By The Nazis STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School Massimo Lolley Teacher: Ivan Obert NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Individual Exhibit 3rd Place [Entry #] 1111 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Mary Wollstonecraft: The First Feminist to Fight For Women’s Education STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Austyn Hughes Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert 2nd Place [Entry #] 1123 [TITLE OF PROJECT] William Wilberforce: Taking a Stand Against British Slave Trade and Slavery STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Jeana Compton Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert 1st Place [Entry #] 1106 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Elizabeth Kenny: Taking A Stand On The Polio Epidemic STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Ryan Zimmerman Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Group Exhibit 3rd Place [Entry #] 1215 [TITLE OF PROJECT] The White Rose Group; A Hazard to Hitler STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Nevada Middle School [Student Name 1] Ezinne Mba Teacher: [Teacher Name] Kim Greer [Student Name 2] Tylin Page Heathman [Student Name 3] [Student Name 4] 2nd Place [Entry #] 1212 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Riots for the Rights: East German Uprising of 1953 STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Mt. -

Gwendolyn Mink Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Gwendolyn Mink Daughter of the Honorable Patsy Takemoto Mink of Hawaii Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript March 14, 2016 Office of the Historian U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. “Well, I think that every little thing—or maybe not so little thing—that the women in Congress dared to speak about, whether it was, you know, not having gym access in the 1960s, or insisting that Anita Hill be heard in 1991, to insisting that certain kinds of women’s issues get a full hearing—I think all of those things have been part of the story of women in Congress, and part of my mother’s story of being a woman in Congress. I think that what she took from her service was a constant reminder to herself of how important it is that women serve in Congress. Because one woman can’t accomplish what 218 women could, right? And so her goal was parity for women, for the whole full range of women’s voices. I think she hoped that the legacy of being the first woman of color, and being a woman who was willing to talk about women, you know, that that would be part of what she would leave to the future.” Gwendolyn Mink March 14, 2016 Table of Contents Interview Abstract i Interviewee Biography i Editing Practices ii Citation Information ii Interviewer Biography iii Interview 1 Notes 40 Abstract In this interview, Gwendolyn Mink reflects on the life and career of her mother, the late Congresswoman Patsy Takemoto Mink of Hawaii, the first woman of color and the first Asian- American woman to serve in the U.S. -

Congressional Record—Senate S3113

May 23, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S3113 student loans in exchange for a two- SUBMITTED RESOLUTIONS Whereas, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter year commitment at an NHSC-ap- nominated Patsy Takemoto Mink to serve as proved site, within two years of com- Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and pleting their residency. Accepted par- SENATE RESOLUTION 219—HON- International Environmental and Scientific ORING THE LIFE AND LEGACY Affairs; ticipants may serve as primary care Whereas, in 2003, Patsy Takemoto Mink medical, dental, or mental/behavioral OF PATSY TAKEMOTO MINK, THE FIRST WOMAN OF COLOR TO was inducted into the National Women’s Hall health clinicians. of Fame; SERVE IN CONGRESS NHSCLRP provides critical relief to Whereas, on November 24, 2014, Patsy physicians who have completed pediat- Ms. HIRONO (for herself, Mr. SCHATZ, Takemoto Mink was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the high- rics or psychiatry residency training Ms. BALDWIN, Mr. BOOKER, Ms. CANT- WELL, Ms. CORTEZ MASTO, Ms. est civilian honor of the United States; programs; however, pediatric sub- Whereas November 3, 2019, marks the 55th DUCKWORTH, Mrs. FEINSTEIN, Mrs. specialists, such as child and adoles- anniversary of the election of Representative cent psychiatrists, are effectively GILLIBRAND, Ms. HARRIS, Ms. HASSAN, Mink to the House of Representatives; and barred from participating due to the Ms. KLOBUCHAR, Mrs. MURRAY, Ms. Whereas Patsy Takemoto Mink was a extra training these physicians are re- ROSEN, Mrs. SHAHEEN, Ms. SMITH, Ms. trailblazer who not only pioneered the way quired to take after completing their STABENOW, Mr. VAN HOLLEN, Ms. WAR- for women and minorities, but also embodied residency. -

ED 078-451 AUTHOR TITLE DOCUMENT RESUME Weisman

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 078-451 AUTHOR Weisman, Martha TITLE Bow Women in Politics View the Role TheirSexPlays in the Impact of Their Speeches ,ontAudienees.. PUB DATE Mar 73 - - NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Communication Assn. (New York, March 1973) - _ - EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Communication (Thought Transfer; Females;_ Persuasive Discourse; *Political Attitudes;.Public Opinion; *Public Speaking; *Rhetorical Criticisn; *Sex Discrimination; Social Attitudes; *Speeches ABSTRACT While investigatingmaterialsfor a new course at City College of New York dealing with the rhetoric of women activists, women who were previously actively Involved in, the political scene* were asked to respoftd to the question, Does the fact that youare =awoolen affect the content, delivery, or reception of your ideas by theAudiences you haye addressed? If so, how? Women of diverse political and ethnic backgrounds replied.._Although the responses were highly subjective, many significant issues were recognized thatcallfor further investigation._While a number of women'denied that sex plays any role intheimpact of their ideas on audiences, others recognized the prejudices they face when delivering Speeches. At the same time* some women who identified the obstacles conceded that these prejudices can often be used to enhancetheir ethos. One of the-most-significant points emphasized was that we may have reached a new national. consciousness toward women politicians. _ FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLECOPY . HOW WOMEN IN POLITICS -

Artifacts Highlighting Women in History at the National Constitution Center

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Denise Venuti Free Ashley Berke Director of Public Relations Public Relations Coordinator 215.409.6636 215.409.6693 [email protected] [email protected] ARTIFACTS HIGHLIGHTING WOMEN IN HISTORY AT THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER PHILADELPHIA, PA (February 10, 2006) – Visitors to the National Constitution Center during the month of March will have the opportunity to discover the tremendous contributions and accomplishments of women pioneers throughout history. In celebration of Women’s History Month, the National Constitution Center has highlighted several artifacts throughout its main exhibition that connect visitors to great events and time periods in women’s history. Representing two of the most significant eras in the history of women in our nation, women’s suffrage and the women’s rights movement of the 1970’s, are an “Ask Santa to Bring a Vote for Mother” stocking and a button from the campaign to ratify an Equal Rights Amendment. Other artifacts include an autograph book from 1876 with the signatures of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and other leaders of the women’s suffrage movement and the robe worn by retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Visitors can also learn more about several important women pioneers throughout history by reading about the impact they had on shaping the Constitution at the American National Tree exhibit in the permanent exhibition. Included on the tree are Bella Abzug, a flamboyant feminist member of House of Representatives; Myra Bradwell, a feminist -

1 Gender and the Law Stories: Learning from the Longstanding Debate the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Lecture --- Feb. 7, 2011 Martha Mino

Gender and the Law Stories: Learning from the Longstanding Debate The Ruth Bader Ginsburg Lecture --- Feb. 7, 2011 Martha Minow1 To give a lecture named for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to this august assembly is an extraordinary honor, and to do so in her company is simply a joy. Justice Ginsburg, your significance to my professional fields of civil procedure, constitutional law, and gender and the law is simply unparalleled. And your place in my own life includes pivotal encouragement as you joined the appellate bench and while I served as a clerked. Later, there was a memorable phone call telling me you nominated me to serve on the board of the American Bar Foundation—an affiliation that changed my research and my relationship with the bar. I will never forget your support as I decided to entitle an article, “Justice Engendered,” in the Harvard Law Review. Your example-- as a short, Jewish woman whose work opens the literal and professional doors I have been lucky enough to enter. Your repeated kindnesses mean more than I can ever say. 1 Dean and Jeremiah Smith, Jr. Professor, Harvard Law School. Thanks to Vicki Jackson, Josephine Minow, Nell Minow, Newton Minow, and Joe Singer for helpful comments, and to the many friends and students who helped with my in efforts in the related work published in Elizabeth Schneider and Stephanie Waldman, Women and the Law Stories (2011) and Martha Minow, In Brown’s Wake: Legacies of America’s Judicial Landmark (2010). 1 I want to take a moment to salute Marty, who I know loved this event and who remains a distinguished, beloved graduate of my school—and the chef of one of the few good meals I had while in Washington. -

A Tribute to Patsy Takemoto Mink

A Tribute to Patsy Takemoto Mink INTRODUCTION Tania Cruz* & Eric K. Yamamoto+ Patsy Takemoto Mink’s life generated a wave of praise for her work as a congressional and community leader. Upon her passing, numerous politicians, women’s groups and civil rights organizations reflected on her lifelong accomplishments, celebrating what an inspiration she had been to women and minorities throughout Hawai`i and the nation. As the first woman of color in Congress, Patsy committed her life to fighting for women’s rights and the rights of the poor and disenfranchised. Through her resounding voice, she ensured that the voices of those whom society had silenced would be heard. Yet, Patsy did more than speak about these causes—her life’s work was a testament to what she believed in and spoke so vehemently about in public. Patsy’s dedication to social justice was extraordinary. For even when the tide of public opinion was against her, she held steadfast to her beliefs and to her mission. Even after her death, her life continues to inspire people who sought to ensure her enduring legacy. In early 2003, four young women of color inspired by Patsy’s work—Tannaz Simyar, Della Au Belatti, Annie Lee and Tania Cruz—with the guidance of Professor Eric Yamamoto and support of Dean Lawrence Foster, conceived of and organized a tribute to Patsy to celebrate her many accomplishments and also to continue the social justice mission she began so many years earlier. On March 13, 2003, the William S. Richardson School of Law hosted “A Tribute to Patsy Mink.” The event, while paying tribute to Patsy, was far more than that. -

Patsy T. Mink LATE a REPRESENTATIVE from HAWAII ÷

im Line) Patsy T. Mink LATE A REPRESENTATIVE FROM HAWAII ÷ MEMORIAL ADDRESSES AND OTHER TRIBUTES HON. PATSY T. MINK ÷z 1927–2002 HON. PATSY T. MINK ÷z 1927–2002 VerDate jan 13 2004 14:15 Jun 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 C:\DOCS\PRINTED\MINK\82489.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE VerDate jan 13 2004 14:15 Jun 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 C:\DOCS\PRINTED\MINK\82489.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) © Mary Ann Changg Photo/Hawaii Patsy T. Mink VerDate jan 13 2004 14:15 Jun 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6688 C:\DOCS\PRINTED\MINK\82489.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE 82489.001 VerDate jan 13 2004 14:15 Jun 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6688 C:\DOCS\PRINTED\MINK\82489.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes HELD IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES TOGETHER WITH MEMORIAL SERVICES IN HONOR OF PATSY T. MINK Late a Representative from Hawaii One Hundred Seventh Congress Second Session ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2003 VerDate jan 13 2004 14:15 Jun 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6686 C:\DOCS\PRINTED\MINK\82489.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing, Chairman Robert W. Ney VerDate jan 13 2004 14:15 Jun 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 C:\DOCS\PRINTED\MINK\82489.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) CONTENTS Page Proceedings in the House of Representatives: Tributes by Representatives: Abercrombie, Neil, of Hawaii ...............