Deborah: the Creation of a Chamber Oratorio in One Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for Cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009

CORO CORO HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009 “Overall, this disc ranks as The Sixteen’s most exciting achievement in its impressive Handel discography.” HANDEL gramophone Choruses HANDEL: Dixit Dominus cor16076 STEFFANI: Stabat Mater The Sixteen adds to its stunning Handel collection with a new recording of Dixit Dominus set alongside a little-known treasure – Agostino Steffani’s Stabat Mater. THE HANDEL COLLECTION cor16080 Eight of The Sixteen’s celebrated Handel recordings in one stylish boxed set. The Sixteen To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16180 He is quite simply the master of chorus and on this compilation there is much rejoicing. Right from the outset, a chorus of Philistines revel in Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound to celebrate Dagon’s festival in Samson; the Israelites triumph in their victory over Goliath with great pageantry in How excellent Thy name from Saul and we can all feel the exuberance of I will sing unto the Lord from Israel in Egypt. There are, of course, two Handel oratorios where the choruses dominate – Messiah and Israel in Egypt – and we have given you a taster of pure majesty in the Amen chorus from Messiah as well as the Photograph: Marco Borggreve Marco Photograph: dramatic ferocity of He smote all the first-born of Egypt from Israel in Egypt. Handel is all about drama; even though he forsook opera for oratorio, his innate sense of the theatrical did not leave him. Just listen to the poignancy of the opening of Act 2 from Acis and Galatea where the chorus pronounce the gloomy prospect of the lovers and the impending appearance of the monster Polyphemus; and the torment which the Israelites create in O God, behold our sore distress when Jephtha commands them to “invoke the holy name of Israel’s God”– it’s surely one of his greatest fugal choruses. -

Deborah Cachet

za 21 sep 2019 20.00 Kamermuziekzaal DEBORAH CACHET Drama Queens © Stefaan Achtergael Biografieën Uitvoerders Deborah Cachet (BE) is sinds 2013 bezig Sofie Vanden Eynde (BE) begon op jonge en programma aan een operacarrière met finaleplekken en leeftijd gitaar te spelen, om later over te prijzen in concoursen als die van Froville en schakelen op luit en teorbe. Ze studeerde Innsbruck. Ze maakte deel uit van Le Jardin bij Philippe Malfeyt en Hopkinson Smith des Voix, het jonge-artiestenprogramma en speelde sindsdien bij groepen als Neue van Les Arts Florissants (Arminda in Hofkapelle Graz, Hathor Consort, a nocte Mozarts Finta Giardiniera), en zong de temporis, Vox Luminis, en in duo met Romina rollen van Dido en Didon in Purcells Dido Lischka, Thomas Hobbs, Emma Kirkby, and Aeneas en Desmarests Didon et Énee Lore Binon, Lieselot De Wilde en Rebecca 19.15 Inleiding door Sofie Taes Francesco Cavalli (1602-1676) in een Europese tournee in het kader van de Ockenden. In 2012 creëerde ze Imago Volgi, deh volgi il piede, uit Gli amori Académie Baroque d’Ambronay gedirigeerd Mundi, een ontmoetingsplaats voor oude — d’Apollo e di Dafne (1640) door Paul Agnew. Ze werkt ondertussen en nieuwe, westerse en oosterse muziek, met ensembles als Les Talens Lyriques, en voor verschillende artistieke disciplines. Deborah Cachet: sopraan Stefano Landi (1587-1639) Pygmalion, Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, De productie Divine Madness kon op veel Edouard Catalan: cello T’amai gran tempo, uit Il secondo libro Collegium 1704 (Alphise in Rameaus Les bijval rekenen, in 2018 gevolgd door In My Sofie Vanden Eynde: luit d’arie musicali (1627) Boréades), Correspondances, Le Poème End is My Beginning, een voorstelling rond Bart Naessens: klavecimbel Harmonique, Scherzi Musicali, Les Muffatti, de fascinerende figuur van Mary Stuart Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) L’Achéron en a nocte temporis, met wie ze al gecreëerd op Operadagen Rotterdam. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXXI, Number 2 Summer 2016 HANDEL’S GREATEST HITS: REPORT FROM HALLE THE COMPOSER’S MUSIC IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BENEFIT CONCERTS Buried in The London Stage are advertisements for concerts including or devoted to Handel’s music. Starting in the 1710s and continuing through the eighteenth century, musicians of all types used Handel’s music on their concert programs, most especially during their benefit evenings.1 These special events were dedicated to promoting a sole performer (or other members of the theatrical staff at a particular playhouse or concert hall). As was tradition, performers would have organized these events from beginning to end by hiring the other performers, renting the theater, creating advertisements, soliciting patrons, and The Handel Festival in Halle took place this year from programming the concert. Advertisements suggest that singers Friday, May 27 to Sunday, June 12, 2016 with the theme “History – and instrumentalists employed Handel’s music in benefit concerts Myth – Enlightenment.” Following the pattern established last year, for their own professional gain. They strategically programmed the Festival extended over three weekends. The Opening Concert, particular pieces that would convey specific narratives about their which had been a feature of recent Festivals, was not given. Instead, own talents, as well as their relationship to the popular composer. the first major musical event was the premiere of the new staging Benefit concerts were prime opportunities for performers of Sosarme, Re di Media at the Opera House, using performing to construct a narrative, or a story, through their chosen program. materials prepared by Michael Pacholke for the Hallische Händel- On the one hand, concert programs allowed performers to Ausgabe (HHA). -

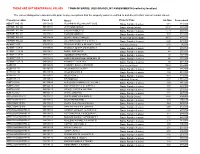

TOWN of BARRE 2020 GRAND LIST ASSESSMENTS (Sorted by Location)

THESE ARE NOT REAPPRAISAL VALUES TOWN OF BARRE 2020 GRAND LIST ASSESSMENTS (sorted by location) The values diplayed are assessments prior to any exemptions that the property owner is entitled to and do not reflect current market values. Property Location Parcel ID Owner Property Type Lot Size Assessment ABBOTT AVE 100 035/004.00 SUGARMAN WILLIAM & NATHALIE Single Family < 6 acres 6.71 181,100 AIRPORT RD 126 005/107.01 WHITCOMB MASON Single Family (>6ac) 39.38 403,800 AIRPORT RD 146 005/107.00 LACLAIR ROBERT B Single Family < 6 acres 5.79 259,600 AIRPORT RD 182 005/108.02 HOWARD JAMES G Single Family < 6 acres 7.07 332,800 AIRPORT RD 211 005/109.04 BENOIT JOHN & PAMELA Residential Outbuildings 93.75 475,750 AIRPORT RD 244 005/108.01 GAUTHIER TIMOTHY P & VICKY J Single Family < 6 acres 2.20 221,900 AL MONTY DR 040/007.02 TRUDO WHITNEY & MCNANEY TYLER Res Vacant Rural 1.10 38,000 AL MONTY DR 01 040/006.00 TROMBLY JOHN P & MARJORIE A Single Family < 6 acres .40 245,860 AL MONTY DR 05 040/006.01 BABEL JUNE MARIE Single Family < 6 acres .40 235,650 AL MONTY DR 08 040/007.01 GOSSELIN CHRISTINA L Single Family < 6 acres .90 132,380 AL MONTY DR 13 040/006.02 MULLIGAN MARGARET M RE REV TR Single Family < 6 acres .40 177,900 AL MONTY DR 15 040/006.03 MCNANEY TYLER W & Single Family < 6 acres .80 287,300 ALLEN ST 005/128.00 LAMBERT JESSE & JENNIFER Res Vacant Rural 75.44 345,900 ALLEN ST 171 005/127.00 WILLIAMS DAVID & RITA Single Family < 6 acres 1.50 140,400 ALLEN ST 194 005/128.03 WILLIAMS GARY S Single Family < 6 acres 1.84 218,900 ALLEN ST 212 -

Loyola University Rome Center Yearbook 1989-1990

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Rome Center Yearbooks Collections 1990 Loyola University Rome Center Yearbook 1989-1990 Loyola University Rome Center Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/rome_center_yearbooks Part of the Italian Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Loyola University Rome Center, "Loyola University Rome Center Yearbook 1989-1990" (1990). Rome Center Yearbooks. 36. https://ecommons.luc.edu/rome_center_yearbooks/36 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Collections at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rome Center Yearbooks by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. ~~ MCMLXXXIX· MYM ~ Loyola Rome Center 1989 - 1990 Dr. Martin Molnar Rome Center Librarian It is with deep appreClatlOn, esteem and affection that we dedicate our yearbook to Dr. Martin Molnar, Librarian at the Rome Center since 1967. Those who know Dr. Molnar also know the time, energy, care and unfailing devotion he has given to his work and to the faculty and students of the Rome Center campus for so many years. Kate Felice Assistant Director and Registrar Dr. Paolo Giordano Director and Academic Dean ADMINISTRATION John Felice Associate Director and Dean of Students Adrienne Ward Secretary to Director Rev. Clyde Leblanc, S.] Chaplain Giorgio Trancalini Business Office Katie Montalto Beatrice Ghislandi Dr. Ettore Loll ini , M.D . Maria Cempanari Director of Student Activities Assistant Librarian School Physician Business Office Manager Dr. -

Town of Manchester, Ct Real Estate Property List (With Assessment Data) Listing Ownership As of May 17, 2018

TOWN OF MANCHESTER, CT REAL ESTATE PROPERTY LIST (WITH ASSESSMENT DATA) LISTING OWNERSHIP AS OF MAY 17, 2018 To Search in Adobe Reader / Acrobat: Press Control Key + F and enter in the Street Name you are looking for CONDO STREET UNIT # STREET NAME # OWNER'S NAME CO-OWNER'S NAME 17 AARON DRIVE ANSALDI ASSOCIATES 20 AARON DRIVE BRODEUR MICHAEL P & CYNTHIA L 2 ABBE ROAD BUGNACKI MICHAEL 9 ABBE ROAD BUGNACKI MICHAEL & SHEILA 23 ABBE ROAD BUGNACKI MICHAEL 37 ABBE ROAD ZYREK ANDREW R & ZYREK GEORGE P 3 ACADEMY STREET ZIMOWSKI AMIE C 11 ACADEMY STREET LALIBERTE ERNEST A & MARGARET 15 ACADEMY STREET LAVOIE DAVID & KRISTIN 16 ACADEMY STREET CURRY RICHARD L L/U & JAMES F & OLINATZ LAURA J 19 ACADEMY STREET RYAN ERIN M 20 ACADEMY STREET RIVAL JESSICA & JAMES 23 ACADEMY STREET WHITAKER RICHARD A & JOANN B 30 ACADEMY STREET SNYDER JOSEPH T 37 ACADEMY STREET COTE RONALD R & DIANE L 47 ACADEMY STREET MOORE COREY ANTONIO 48 ACADEMY STREET TEDFORD GORDON W 49 ACADEMY STREET CZAPOROWSKI JOAN M & JANE H 54 ACADEMY STREET THOMAS MONIQUE A 55 ACADEMY STREET WAGGONER ALBERT A JR & SUZAN E FERAGNE PAUL & LAUREL 57 ACADEMY STREET LETITIA MARGARET C 58 ACADEMY STREET VAIDA MATTHEW R 62 ACADEMY STREET HITE DEREK & SHACARRA 24 ADAMS STREET MANCHESTER SPORTS CENTER INC 33 ADAMS STREET RETAIL PROPERTY TWO LLC 41 ADAMS STREET CONNECTICUT SOUTHERN RAILROAD INC ATTN TAX DEPARTMENT 45 ADAMS STREET FAY JOHN P 58 ADAMS STREET POM-POM GALI LLC 60 ADAMS STREET POM-POM GALI LLC 81 ADAMS STREET EIGHTY ONE ADAMS STREET LLC 81 ADAMS STREET EIGHTY ONE ADAMS STREET LLC 109 ADAMS -

THE MAGIC of HANDEL January 24 + 26, 2020 PROGRAM NOTES the MAGIC MUSICAL OPPORTUNITIES

EXPERIENCE LIVING MUSIC THE MAGIC OF HANDEL January 24 + 26, 2020 PROGRAM NOTES THE MAGIC MUSICAL OPPORTUNITIES OF HANDEL Born in Halle, George Frideric Handel’s talent and passion for music was evident from a young age and although he attended the University of Halle for a short January 24 + 26, 2020 at 7:00PM Streamed Online period of time, he soon put all of his time and energy towards music. By 1703, he GBH’s Fraser Studio 2,526th Concert was in Hamburg; two years later, his first opera, Almira, successfully premiered there. Not long after this, he moved to Rome, where he impressed wealthy patrons with his compositions as well as his performance skills. In 1710, Handel was again thinking about new prospects as he journeyed back to Germany where the Elector of Hanover (and future king of England) appointed him Kapellmeister. PERFORMERS His new employer allowed Handel to travel; within one month of his appointment, Emily Marvosh, host he had left Hanover for London, with an extended stay in Düsseldorf. Once in Aisslinn Nosky, violin London, Handel did not waste time in establishing his reputation as a composer Susanna Ogata, violin with a work in honor of the Queen’s birthday and the premiere of his opera Guy Fishman, cello Rinaldo in February 1711. With these successes in hand Handel returned to Ian Watson, harpsichord Hanover for a little over a year, requesting permission to return to England in the latter part of 1712. As in Italy, Handel accepted the support of wealthy aristocrats in and around PROGRAM London, such as the Earl of Burlington, in whose home he lived between 1714 and 1715, and the Duke of Chandos. -

Norma Ariodante

NORMA ARIODANTE PROGRAM FALL 2016 Great opera lives here. Proud sponsor of the Canadian Opera Company’s 2016/2017 Season. 16-1853 Canadian Opera Company Fall House Program Ad_Ev2.indd 1 2016-08-05 3:20 PM CONTENTS A MESSAGE FROM GENERAL DIRECTOR 4 WHAT’S PLAYING: ALEXANDER NEEF NORMA 10 THE DRAMA BEHIND BELLINI’S At its most fundamental, opera NORMA is about compelling, imaginative, 13 GET TO KNOW inspiring storytelling. When music ELZA VAN DEN HEEVER and voices collaborate in the act of storytelling the result can be an 14 WHAT’S PLAYING: ARIODANTE extremely powerful expression of humanity. 20 FROM ARTASERSE TO ARIODANTE This season at the COC we have BIOGRAPHIES: NORMA a remarkable array of stories 25 for you to enjoy—from tales of 28 BIOGRAPHIES: ARIODANTE ancient druids and princesses, to fictional opera divas; from mythic THE BMO EFFECT 31 characters in a mythical land to 32 BACKSTAGE AND BEYOND real-life champions of human rights. Their stories may be different, but 35 BACKING A WINNING TEAM they are deeply felt and intensely 36 MATTHEW AUCOIN: communicated, and they are our Doing What Comes Naturally stories. In them, we see our own struggles and successes, joys and 38 CENTRE STAGE: fears, and we are grateful for the An Experience You Won’t Forget shared experience. 40 MEET THE GUILDS During this 10th anniversary season 42 AN OPEN LETTER FROM JOHANNES DEBUS in our marvelous opera house, the Four Seasons Centre for the 44 REMEMBERING LOUIS RIEL Performing Arts, I am particularly to achieving the greatest proud that the COC is a home for heights of artistic excellence, in, 49 CREATING A BETTER DONOR once again, an all-COC season. -

A Guide to Handel's London in Germany, Lived in Italy for Four Years, and Made London His Home by Carol J

Preface George Frideric Handel was born A Guide to Handel's London in Germany, lived in Italy for four years, and made London his home by Carol J. Schaub for the last fifty years of his life. With musical traditions firmly established in many European cities, why did Handel choose London? As today's ·residence at Cannons, Brydges' residents and tourists are aware, grand house near Edgeware in Mid London is one of the finest cultural dlesex. Handel's first biographer, centers in the world. We can only John Mainwaring, wrote in 1760 speculate that Handel had the same that Cannons was "a place which feeling about. the city when he was then in all its glory, but arrived in 1710. Although many of remarkable for having much more the· landmarks associated with of art than nature, and much more Handel's life in London have disap cost than art."2 Handel stayed at 'peared over the intervening cen Cannons until 1719 when his love turies, it is hoped that this guide will for the theater and the newly assist all music lovers in retracing established Royal Academy lured some of Handel's footsteps. him back to London. In 1723, Handel moved to the Part I house at 25 Brook Street where he A Guide to the Past lived until his death on 14 April 1759. It was in a neighborhood in Setting the Stage ... habited by "people of quality"3 and Handel's London did not have the Handel must have been quite com convenience of an efficient fortable there. -

ARIODANTE.Indd 1 2/6/19 9:32 AM

HANDEL 1819-Cover-ARIODANTE.indd 1 2/6/19 9:32 AM LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO Table of Contents MICHAEL COOPER/CANADIAN OPERA COMPANY OPERA MICHAEL COOPER/CANADIAN IN THIS ISSUE Ariodante – pp. 18-30 4 From the General Director 22 Artist Profiles 48 Major Contributors – Special Events and Project Support 6 From the Chairman 27 Opera Notes 49 Lyric Unlimited Contributors 8 Board of Directors 30 Director's Note 50 Commemorative Gifts 9 Women’s Board/Guild Board/Chapters’ 31 After the Curtain Falls Executive Board/Young Professionals/Ryan 51 Ryan Opera Center 32 Music Staff/Orchestra/Chorus Opera Center Board 52 Ryan Opera Center Alumni 33 Backstage Life 10 Administration/Administrative Staff/ Around the World Production and Technical Staff 34 Artistic Roster 53 Ryan Opera Center Contributors 12 Notes of the Mind 35 Patron Salute 54 Planned Giving: e Overture Society 18 Title Page 36 Production Sponsors 56 Corporate Partnerships 19 Synopsis 37 Aria Society 57 Matching Gifts, Special anks, and 21 Cast 47 Supporting Our Future – Acknowledgements Endowments at Lyric 58 Annual Individual and Foundation Support 64 Facilities and Services/eater Staff NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH NATIONAL On the cover: Findlater Castle, near Sandend, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Photo by Andrew Cioffi. CONNECTING MUSIC WITH THE MIND – pp. 12-17 2 | March 2 - 17, 2019 LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO From the General Director STEVE LEONARD STEVE Lyric’s record of achievement in the operas of George Frideric Handel is one of the more unlikely success stories in any American opera company. ese operas were written for theaters probably a third the size of the Lyric Opera House, and yet we’ve repeatedly demonstrated that Handel can make a terrifi c impact on our stage.