The Imagery of Sue Coe: Making Visible the Invisible Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of American Studies, 52(3), 660-681

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Explore Bristol Research Savvas, T. (2018). The Other Religion of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Journal of American Studies, 52(3), 660-681. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875817000445 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1017/S0021875817000445 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via CUP at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-american-studies/article/other-religion-of-isaac- bashevis-singer/CD2A18F086FDF63F29F0884B520BE385. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/pure/about/ebr-terms 1 The Other Religion of Isaac Bashevis Singer Theophilus Savvas, University of Bristol This essay analyzes the later fiction of Nobel Prize-winning writer Isaac Bashevis Singer through the prism of his vegetarianism. Singer figured his adoption of a vegetarian diet in 1962 as a kind of conversion, pronouncing it a “religion” that was central to his being. Here I outline Singer’s vegetarian philosophy, and argue that it was the underlying ethical precept in the fiction written after the conversion. I demonstrate the way in which that ethic informs the presentation of both Judaism and women in Singer’s later writings. -

SUE COE at James Fuentes Essex in Collaboration with Galerie St

JAMES FUENTES 55 Delancey Street New York, NY 10002 (212) 577-1201 [email protected] SUE COE JAMES FUENTES ESSEX Paintings 81 Essex St, New York NY 10002 May 6–June 6, 2021 Wednesday–Sunday, 10am–6pm James Fuentes is pleased to present paintings by SUE COE at James Fuentes Essex in collaboration with Galerie St. Etienne. Sue Coe is a British-American artist and activist working across drawing, printmaking, and painting. Coe studied at the Royal College of Art in London and emigrated to the US in the early 1970s, where she lived in New York City until upstate New York in 2002. Coe is known for her striking, propaganda-like visual commentary on major events and figures in culture and politics, rendered in stark visual contrast through her highly recognizable palette of black, white, and red. Coe’s experience growing up in close proximity to a slaughterhouse informed her lifelong animal rights activism, which remains interconnected within both her wider political activism and her output as an artist. In the decades since, Coe’s work has focused on factory farming, sweat shops, reproductive rights, housing, the prison system, war, the AIDS crisis, and the South African apartheid, often through depictions of key events and dates as marked by their presence in mass media. As well as being presented in museum and gallery exhibitions internationally, Coe’s graphic work has also been regularly published in periodicals like The New York Times, The New Yorker, Time Magazine, Newsweek, and others, delivering her powerful commentary on as a broad a basis as possible. -

Download Download

Canadian Journal of Disability Studies Published by the Canadian Disability Studies Association Association Canadienne des Études sur le handicap Hosted by The University of Waterloo www.cjds.uwaterloo Tricky Ticks and Vegan Quips: The Lone Star Tick and Logics of Debility Joshua Falek Gender, Feminist and Women’s Studies, York University [email protected] Cameron Butler Social Anthropology, York University [email protected] Abstract In this article, we explore the discourse around the Lone Star tick, predominately through the platform of Twitter, in order to highlight the way the tick is imagined as a potential tool for increasing veganism, as the Lone Star tick’s bite has been found to cause allergies to a carbohydrate found in red meat. In particular, the article questions why the notion of tick-as- vegan-technology is so widespread and easily called forward. In order to explain this pattern, we turn to Sunaura Taylor’s monograph, Beasts of Burden and Jasbir Puar’s notion of debility. Taylor’s monograph provides a framework for analyzing the imbrications of power between ableism and speciesism. Puar’s debility helps articulate how the imagination of widespread red meat allergies is an imagination of decapacitation. Puar’s analysis of the invisibilizing of debility also helps reveal how both ticks and humans are debilitated and instrumentalized in this articulated fantasy. We argue that the governance impulse in these discourses reflect a continued alignment with biopolitical forces that always designate some lives as worthy of care and others as useable, which is fundamentally at odds with broader goals of animal liberation. -

Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights

Portland State University PDXScholar Book Publishing Final Research Paper English 5-2017 Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights Gloria H. Mulvihill Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Publishing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mulvihill, Gloria H., "Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights" (2017). Book Publishing Final Research Paper. 26. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper/26 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Publishing Final Research Paper by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Mulvihill 1 Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights Gloria H. Mulvihill MA in Book Publishing Thesis Spring 2017 Mulvihill 2 Abstract Though many of us have heard the mantra that we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, marketers in book publishing bank on the fact that people do and will continue to buy and read books based not only on content, but its aesthetic appeal. This essay will examine the top four marketing trends that can be observed on the Amazon listings for books published on animal rights within the last ten years, specifically relating to titles, cover design, and the intended audience. From graphic adaptations of animals to traditional textbook approaches and animal photography, publishers are striving to evoke interest and investment in literature concerning a politically charged and inherently personal topic. -

Freaks, Elitists, Fanatics, and Haters in Us

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ANIMAL PEOPLE: FREAKS, ELITISTS, FANATICS, AND HATERS IN U.S. DISCOURSES ABOUT VEGANISM (1995-2019) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Samantha Skinazi June 2019 The Dissertation of Samantha Skinazi is approved: ________________________________ Professor Sean Keilen, Chair ________________________________ Professor Carla Freccero ________________________________ Professor Wlad Godzich ______________________________ Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Samantha Skinazi 2019 Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES IV ABSTRACT V DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT VII INTRODUCTION: LOVING SPECIES 1 NOTES 21 FREAKS 22 RIDICULE: THAT JOKE ISN'T FUNNY ANYMORE 28 EMPATHY AND SHAME: OMNIVORE DILEMMAS IN THE VEGAN UTOPIA 41 TERRORS: HOW DO YOU KNOW IF SOMEONE'S VEGAN? 64 CONCLUSION: FROM TEARS TO TERRORISM 76 LIST OF FIGURES 79 NOTES 80 ELITISTS 88 LIFESTYLE VEGANISM: GOOP AND THE WHITE WELLNESS VEGAN BRAND 100 BLINDSPOTTING VEGANISM: RACE, GENTRIFICATION, AND GREEN JUICE 112 DEMOCRATIC VEGANISM: OF BURGERS AND PRESIDENTS 131 CONCLUSION: THE SPECTER OF NATIONAL MANDATORY VEGANISM 153 NOTES 156 FANATICS 162 WHY GIVE UP MEAT IN THE FIRST PLACE? 170 MUST IT BE ALL THE TIME? 184 WHY TELL OTHERS HOW TO LIVE? 198 CONCLUSION: MAY ALL BEINGS BE FREE FROM SUFFERING? 210 NOTES 223 CONCLUSION: HATERS 233 NOTES 239 REFERENCES 240 iii List of Figures Figure 1.1: Save a cow eat a vegetarian, bumper sticker 79 Figure 1.2: When you see a vegan choking on something, meme 79 Figure 1.3: Fun prank to play on a passed out vegan, meme 79 Figure 1.4: How do you know if someone's vegan? 79 Don't worry they'll fucking tell you, meme iv Abstract Samantha Skinazi Animal People: Freaks, Elitists, Fanatics, and Haters in U.S. -

Sue Coe: I Am an Animal Rights Activist Artist

S UE COE: I AM AN A NIMAL RIGHTS A CTIVIST ARTIST Sue Coe, one of the most committed activist artists in America, has during her thirty-five-year career charted an idiosyncratic course through an environment that is at best ambivalent toward art with overt socio-political content. In this issue of Antennae, the artist presents a new portfolio of images on the subject of animal welfare. Questions by Giovanni Aloi and Rod Bennison Giovanni Aloi and Rod Bennison: Your work murder. I am an animal rights activist artist. 50 seems to have more recently focused on a billion non human animals are slaughtered every wider range of subject than ever before. Are year. This number does not include oceanic life. there specific reasons for this? They bleed red, same us. The predictable answer is I grew up a block away from a slaughterhouse and Sue Coe: Don't think so. I have never seen wide lived in front of an intensive hog farm, so was range as being particularly desirable. I could draw accustomed to being around slaughter. My a tree for the rest of my life, and that tree could childhood was dripping in blood, but I would hope incorporate the entire history of culture. My that, personal psychology aside, the apology we preference is to choose a topic, or have it choose owe non-human animals for their suffering, at our me, and research it and do it well over a decade. hands, is more of a motivator. Aloi and Bennison: Your graphic portrayal of Aloi and Bennison: You have been producing hammer head sharks being de-finned and animal welfare oriented work for many years. -

Animal-Industrial Complex‟ – a Concept & Method for Critical Animal Studies? Richard Twine

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 EDITORAL BOARD Dr. Richard J White Chief Editor [email protected] Dr. Nicole Pallotta Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Lindgren Johnson Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Laura Shields Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Richard Twine Book Review Editor [email protected] Vasile Stanescu Book Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Carol Glasser Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Adam Weitzenfeld Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Cole Web Manager [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For a complete list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board please see the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 1 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 EDITORAL BOARD .............................................................................................................. -

The “Ethics” of Eviscerating Farmed Animals for “Better Welfare” a Presentation by Karen Davis, Phd, President of United Poultry Concerns

The “Ethics” of Eviscerating Farmed Animals for “Better Welfare” A Presentation by Karen Davis, PhD, President of United Poultry Concerns Photo by Frank Johnston, The Washington Post Could A Brain-Dead Chicken ‘Matrix’ Solve Ethical Issues Of Factory Farming? Huffington Post, February 29, 2012 “André Ford, an architecture student from the U.K., wants to bring new meaning to the phrase ‘like a chicken with its head cut off.’” “He proposed his ‘Headless Chicken Solution’ for a project at the Royal College of Art in which he was asked to look for sustainable solutions to the U.K.’s farming inefficiencies.” Various researchers and animal welfarists equate removing brain, sensation, and body parts of farmed animals with the removal or reduction of “suffering.” The primary “beneficiaries” of these “welfare” experiments and bodily excisions are chickens. The traditional surgical removal of body parts of chickens and other farmed animals – debeaking, detoeing, de-winging, dehorning, tail docking, castration, etc. – is now being extended to include proposals for genetic manipulation of farmed animals’ brains, so they will be born without a cerebral cortex, without the ability to feel or Perdue chicken house in Delaware Photo by: David Harp experience themselves or their surroundings. Cognitive ethologist Lesley J. Rogers, in her book Minds of Their Own: Thinking and Awareness in Animals, writes: “In the industrial farming of today, the identities of individual animals are completely lost. Animals in intensive farms are seen as bodies, to be fattened or to lay eggs. Their higher cognitive abilities are ignored and definitely unwanted.” Illustration by Nigel Burroughs Photo of Mary Britton Clouse’s artwork, “A Henmaid’s Tale” The “unwanted” cognitive abilities of chickens and other farmed animals is a basis for laboratory experiments on these animals all over the world. -

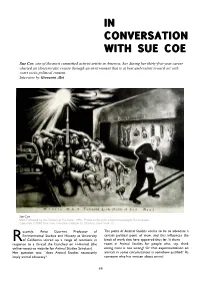

In Conversation with Sue

IN CONVERSATION WITH SUE COE Sue Coe, one of the most committed activist artists in America, has during her thirty-five-year career charted an idiosyncratic course through an environment that is at best ambivalent toward art with overt socio-political content. Interview by Giovanni Aloi Sue Coe Man Followed by the Ghosts of His Meat, 1990. Photo-etching on white heavyweight Rives paper. Copyright ©1990 Sue Coe. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York © ecently, Anita Guerrini, Professor of The point of Animal Studies seems to be to advocate a Environmental Studies and History at University certain political point of view, and this influences the R of California stirred up a range of reactions in kinds of work that have appeared thus far. Is there response to a thread she launched on H-Animal (the room in Animal Studies for people who, say, think online-resource website for Animal Studies Scholars). eating meat is not wrong? Or that experimentation on Her question was: “does Animal Studies necessarily animals in some circumstances is somehow justified? As imply animal advocacy? someone who has written about animal 54 experimentation quite a lot, but who has not In the past, Newspaper and magazine editors unreservedly condemned it, I am not sure that I have a have restricted your freedom of expression place in Animal Studies as it is currently defined.” because of the overt and political content involved with your work. Do you have a story What is your take on this subject? that may not be yet published because deemed ‘too strong’? As one revolutionary in the times of South African apartheid stated “ I agree blacks and whites should co- Some time ago, I stopped negotiating for crumbs with exist, but first blacks have to actually exist.” People the mass media, and decided to publish my work in the have to do what they believe to be right – I am a vegan, form I intended, I can come up with my own dumb and am against all animal exploitation, and choose to be ideas, I do not need editors to tell me their dumb ideas. -

Editorial Antennae Issue 19

EDITORIAL ANTENNAE ISSUE 19 ne of the most defining aspects of Antennae’s status as a multidisciplinary journal has simply been the determination to relentlessly present a variety of perspectives, always delivered by a O diverse range of voices. Some have misinterpreted this ambition as a lack of concern for certain subjects in the human-animal discourse. However, as it was envisioned since its inception, Antennae’s main purpose is not that of takings sides, nor that of telling readers what is right or wrong, in the assumption that that the work of the reader may indeed entail the tasks of deciphering and deciding. For this reason, more than in other previous issue, this present one is consistently shaped by the perspectives and voices of some of the most influential and challenging contemporary thinkers. Antennae is nearing its 5th birthday – the first issue was released in March 2006. Back then it was impossible to imagine that in 2011, we’d be able to gather exclusive interviews from the likes of Peter Singer, Tom and Nancy Regan, Roger Scruton and John Simons all in one issue dedicated to the subject of animal advocacy and the arts. And most importantly, it would have been even harder to imagine that these names would have been interviewed by some of the most exciting scholars who over the past twenty years have consistently shaped the field of human-animal studies itself: Carol Gigliotti, Garry Marvin and Rod Bennison, just to name a few, have all greatly contributed to the shaping of new perspectives through their discussions and questioning. -

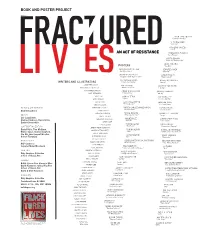

Book and Poster Project an Act of Resistance

BOOK AND POSTER PROJECT IGOR LANGSHTEYN “Secret Formulas” SEYOUNG PARK “Hard Hat” CAROLINA CAICEDO “Shell” AN ACT OF RESISTANCE FRANCESCA TODISCO “Up in Flames” CURTIS BROWN “Not in my Fracking City” WOW JUN CHOI POSTERS “Cracking” SAM VAN DEN TILLAAR JENNIFER CHEN “Fracktured Lives” “Dripping” ANDREW CASTRUCCI LINA FORSETH “Diagram: Rude Algae of Time” “Water Faucet” ALEXANDRA ROJAS NICHOLAS PRINCIPE WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS “Protect Your Mother” “Money” SARAH FERGUSON HYE OK ROW ANDREW CASTRUCCI ANN-SARGENT WOOSTER “Water Life Blood” “F-Bomb” KATHARINE DAWSON ANDREW CASTRUCCI MICHAEL HAFFELY MIKE BERNHARD “Empire State” “Liberty” YOKO ONO CAMILO TENSI JUN YOUNG LEE SEAN LENNON “Pipes” “No Fracking Way” AKIRA OHISO IGOR LANGSHTEYN MORGAN SOBEL “7 Deadly Sins” CRAIG STEVENS “Scull and Bones” EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR MARIANNE SOISALO KAREN CANALES MALDONADO JAYPON CHUNG “Bottled Water” Andrew Castrucci TONY PINOTTI “Life Fracktured” CARLO MCCORMICK MARIO NEGRINI GABRIELLE LARRORY DESIGN “This Land is Ours” “Drops” CAROL FRENCH Igor Langshteyn, TERESA WINCHESTER ANDREW LEE CHRISTOPHER FOXX Andrew Castrucci, Daniel Velle, “Drill Bit” “The Thinker” Daniel Giovanniello GERRI KANE TOM MCGLYNN TOM MCGLYNN KHI JOHNSON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS “Red Earth” “Government Warning” JEREMY WEIR ALDERSON Daniel Velle, Tom McGlynn, SANDRA STEINGRABER TOM MCGLYNN DANIEL GIOVANNIELLO Walter Sipser, Dennis Crawford, “Mob” “Make Sure to Put One On” ANTON VAN DALEN Jim Wu, Ann-Sargent Wooster, SOFIA NEGRINI ALEXANDRA ROJAS DAVID SANDLIN Robert Flemming “No” “Frackicide” -

Vegans, Freaks, and Animals: Toward a New Table Fellowship

Vegans, Freaks, and Animals: Toward a New Table Fellowship Sunaura Taylor American Quarterly, Volume 65, Number 3, September 2013, pp. 757-764 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/aq.2013.0042 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/aq/summary/v065/65.3.taylor.html Access provided by Vienna University Library (1 Nov 2013 08:43 GMT) Vegans, Freaks, and Animals: Towards a New Table Fellowship | 757 Vegans, Freaks, and Animals: Toward a New Table Fellowship Sunaura Taylor This article is excerpted from Beasts of Burden, forthcoming from the Feminist Press. All rights reserved. n September 2010 I agreed to take part in an art event at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin County, California. The Feral Share,1 as Ithe event was named, was one part local and organic feast, one part art fund-raising, and one part philosophical exercise. I was invited to be part of the philosophical entertainment for the evening: I was to be the vegan repre- sentative in a debate over the ethics of eating meat. I was debating Nicolette Hahn Niman, an environmental lawyer, cattle rancher, and author of Righteous Porkchop: Finding a Life and Good Food beyond Factory Farms. My partner, David, and I got to the event on time, but spent the first forty minutes or so sitting by ourselves downstairs while everyone else participated in the art event, which took place on an inaccessible floor of the building. Our only company was a few chefs busily putting the finishing touches on the evening’s meal—a choice of either grass-fed beef or cheese ravioli.