India: the Next Economic Giant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2015-2Nd INTERIM DIVIDEND

NMD_Div_YC_20_2014-2015-2ndINTERIM NMDC LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 1 NATURE OF AMOUNT : AMOUNT FOR UNCLAIMED AND UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE DIVIDEND YEAR:2014-2015-2nd INTERIM ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/FATHER NAME(S)/ADDRESS DPID/CLIENT ID/FOLIO AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. NO. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1.A ARUN KUMAR 47200 1204720002215843 170.00 05/03/2022 3389301 ANALA PRABHAKAR RAO QR NO B 1 9 SBI COLONY SECTOR 8 BHILAI DURG 490006 2.A B KALYANI IN300513 16047812 55.00 05/03/2022 3386045 B H KALYANI BISMILA MANZIL RAIVAGHA AT AND PO ALINA TALUKA MAHUDHA ALINA GUJARAT 387305 3.A CHELLAPPAN 38400 1203840000482881 425.00 05/03/2022 3393039 ALWAR 94/4-PASUPATHI SIVAN COLONY OPP-PONMUDI HOSPITAL,BEEACH RD ERULAPPAPURAM-NGL NAGERCOIL 629001 4.A J DAWOOD 36000 1203600001267162 43.00 05/03/2022 3399932 ABDUL KHADER JAILANI OLD NO 36 NEW NO 52 THIRUVALLUVAR STREET CHENNAI SAIDAPET SOUTH CHENNAI CHENNAI 600033 5.A K BAKSHI IN300206 10270455 425.00 05/03/2022 3382488 LATE SHS P BAKSHI FLOT NO - 534 POCKET - V , PHASE-I MAYUR VIHAR DELHI 110091 6.A M ASHRAF 44500 1204450000154528 38.00 05/03/2022 3393649 MALIYACKAL BAPU MOHAMMEDALI ARAKKAL HOUSE KALLUR PO VADEKKEKAD TRICHUR 679562 7.A M SINGAIAH IN301356 20417058 425.00 05/03/2022 3392106 MUDDAIAH TYPE III/31 SOUTH BLOCK DONIMALAI 583118 8.A MARY STELLA 10900 1201090001882539 -

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Hindu Responses to Religious Diversity and the Nature of Post-Mortem Progress

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Hindu Responses to Religious Diversity and the Nature of Post-Mortem Progress The last two hundred years of Hindu–Christian encounters have produced distinctive forms of Hindu thought which, while often rooted in the broad philosophical-cultural continuities of Vedic outlooks, grappled with, on the one hand, the colonial pressures of European modernity, and, on the other hand, the numerous critiques by Christian theologians and missionaries on the Hindu life-worlds. Thus, the spectrum of Hindu responses from Raja Rammohun Roy through Swami Vivekananda to S. Radhakrishnan demonstrates attempts to creatively engage with Christian representations of Hindu belief and practice, by accepting their prima facie validity at one level while negating their adequacy at another. For instance, these figures of neo-Hinduism accepted that such ‘corruptions’ as Hinduism’s alleged idol- worship, anti-worldly ethic, caste-based distinctions and the like were all too visible on the socio-cultural domain, while they formulated revamped Vedic or Vedantic visions within which these were to be either rejected as excrescences or given demythologised interpretations. In Swami Vivekananda, we find on some occasions a more strident rejection of certain aspects of western civilization as steeped in materialist ‘excesses’ which needed to be purged through the light of Vedantic wisdom. Through such hermeneutical processes of retrieval, often carried out within contexts structured by British colonialism, these figures were able to offer forms of Hinduism that were signifiers not of the Oriental depravity that the British administrators, scholars and missionaries had claimed to perceive on the Indian landscapes but of a spiritual depth that transcended national, cultural and ethnic boundaries. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Arun Shourie

PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com ARUN SHOURIE ARTICLES ON KASHMIR PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 ARUN SHOURIE...................................................................................................................1 2.0 HAZRATBAL MOSQUE CRISIS: HOW AND WHY IT HAPPENED?............................2 3.0 CALAMITIES COME AND GO, BUT DECISION TO STAY REMAINS........................6 i http://ikashmir.net/arunshourie/index.html PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com TABLE OF CONTENTS ii http://ikashmir.net/arunshourie/index.html PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Arun Shourie: Articles on Kashmir 1.0 ARUN SHOURIE Arun Shourie (born 1941) is among India's best known and controversial commentators on current and political affairs. He backs his distinctive writing and his conscientiously independent perspective with rigorous analysis and meticulous research. Born in Jalandhar, Punjab, India, he studied at Modern School and St. Stephen's College in Delhi. He obtained his doctorate in Economics from Syracuse University in the United States. He has been an economist with the World Bank, a consultant to the Planning Commission, India and editor of the Indian Express (a leading Indian newspaper). In a series of remarkable exposés, many of which he wrote himself, Shourie and the Indian Express uncovered corruption in the highest echelons of the government and exposed several major scandals of the era, including what has been dubbed “India’s Watergate.”Shourie started a one- man crusade in 1981 against Abdul Rahman Antulay, the chief minister of Maharashtra State, who extorted millions of dollars from businesses dependent on state resources and put the money in a private trust named after Indira Gandhi. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

The Lockdown to Contain the Coronavirus Outbreak Has Disrupted Supply Chains

JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SINCE 1932 The lockdown to contain the coronavirus outbreak has disrupted supply chains. One crucial chain is delivery of information and insight — news and analysis that is fair and accurate and reliably reported from across a nation in quarantine. A voice you can trust amid the clanging of alarm bells. Vajiram & Ravi and The Indian Express are proud to deliver the electronic version of this morning’s edition of The Indian Express to your Inbox. You may follow The Indian Express’s news and analysis through the day on indianexpress.com eye THE SUNDAY EXPRESSMAGAZINE Find Me on a NEWDELHI,LATECITY Hill in Imphal AUGUST30,2020 ‘Battlefield diggers’ look for 18PAGES,`6.00 remains of soldierswho died (`8PATNA&RAIPUR,`12SRINAGAR) in Manipur hills in WWII DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH,DELHI,JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM PAGES 15, 16, 17 Reliance Retail adds UNLOCK 4.0: CENTRE’S GUIDELINES Future Group firms MetrotostartSept7,no to its shopping cart statelockdownsoutside D Sale of Big Bazaar, E Whythis Easyday part of iskeyto PLAIN E containmentzones ● RILplans Rs 24,713-cr deal EX THE DEAL strengthens Studentscan visitschools, colleges; PRANAVMUKUL& RIL’sposition in the coun- WHAT’SALLOWED GEORGEMATHEW try’s retail ecosystem by gatherings of up to 100fromSept21 ■ MetrofromSept7 NEWDELHI,MUMBAI, enabling it to control ■ Congregations of up AUGUST29 nearly athirdoforganised The Centrehas also allowedop- to 100peoplefromSept retail revenues, and also DEEPTIMANTIWARY eration -

Dr. Isher Judge Ahluwalia on HER

Remembering Dr. Isher Judge Ahluwalia ON HER BIRTH ANNIVERSARY Isher Judge Ahluwalia was inspired by issues of urbanisation and governance Rajat Kathuria | Indian Express | September 29, 2020 For a scholar of her stature and with all the exceptional achievements to boot, she could well have rested on her laurels. There was nothing left to prove. But that was not Isher. Isher last public appearance on ICRIER's platform was in February this year at the launch of Montek Singh Ahluwalia’s memoir, Backstage. When the phone rang to inform me of the passing away of Isher Judge Ahluwalia, former chairperson of ICRIER and my former boss, the world stopped, if only for an instant, as if someone had pressed a pause button. The poignancy of the moment was accompanied by a flashback of memories of a smiling Isher with perfectly groomed salt and pepper hair, announcing with grace, dignity, poise, charm and brilliance, the start of another conference at ICRIER. Her public persona was larger than life. Behind the exterior, there was also an Isher who was compassionate, supportive, loyal and who possessed almost a childlike desire to learn about issues that drew her interest. My close association with Isher began fittingly with a conference in April 2012. I was to take over as director and chief executive of ICRIER later that year. She decided to “induct” me at an ICRIER event in Vigyan Bhavan where the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was the chief guest. An updated edition of the festschrift, India’s Economic Reforms and Development: Essays for Manmohan Singh, co-edited by Isher was to be presented to him. -

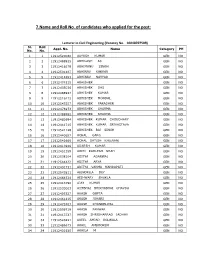

7.Name and Roll No. of Candidates Who Applied for the Post

7.Name and Roll No. of candidates who applied for the post: Lecturer in Civil Engineering (Vacancy No. 16040707509) Sl. Roll Appl. No. Name Category PH No. No. 1 1 11912520060 AAYUSH KUMAR GEN NO 2 2 11912498925 ABHILASH AS GEN NO 3 3 11912416578 ABHIMANU SINGH GEN NO 4 4 11912501467 ABHINAV KAKKAR GEN NO 5 5 11912414553 ABHINAV NAYYAR GEN NO 6 6 11912474515 ABHISHEK GEN NO 7 7 11912405036 ABHISHEK DAS GEN NO 8 8 11912488927 ABHISHEK KUMAR GEN NO 9 9 11912516172 ABHISHEK MONDAL GEN NO 10 10 11912543257 ABHISHEK PARASHER GEN NO 11 11 11912476973 ABHISHEK SHARMA GEN NO 12 12 11912488982 ABHISHEK SHARMA GEN NO 13 13 11912482694 ABHISHEK KUMAR CHOUDHARY GEN NO 14 14 11912441715 ABHISHEK KUMAR SRIVASTAVA GEN NO 15 15 11912521128 ABHISHEK RAJ SINGH GEN NO 16 16 11912440657 ACHAL GARG GEN NO 17 17 11912542669 ACHAL SATISH KHILNANI GEN NO 18 18 11912413946 ADARSH KUMAR GEN NO 19 19 11912451359 ADITI KAMLESH SHAH GEN NO 20 20 11912508104 ADITYA AGARWAL GEN NO 21 21 11912544422 ADITYA ARYA GEN NO 22 22 11912431731 ADITYA VARMA MANDAPATI GEN NO 23 23 11912543811 AIENDRILA DEY GEN NO 24 24 11912464534 AISHWARY SHUKLA GEN NO 25 25 11912413790 AJAY KUMAR GEN NO 26 26 11912533003 AJITBHAI BHIKHABHAI CHAVDA GEN NO 27 27 11912495327 AKASH GUPTA GEN NO 28 28 11912461215 AKASH JOHARI GEN NO 29 29 11912475707 AKASH KHANDELWAL GEN NO 30 30 11912509719 AKASH PANWAR GEN NO 31 31 11912413727 AKASH SHRIDHARRAO JADHAV GEN NO 32 32 11912526221 AKEEL AMJAD GOLWALA GEN NO 33 33 11912486673 AKHIL AMBOOKEN GEN NO 34 34 11912431920 AKHILA M GEN NO 35 35 11912491351 -

Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr

Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate All India Federation of Tax Practitioners Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate – Remembering the Legend - A Tribute Regd. Office : 215, Rewa Chambers, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai - 400 020. All India Federation Tel.: 022-2200 6342 / 63 / 4970 6343 of Tax Practitioners E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.aiftponline.org Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate – Remembering the Legend - A Tribute Regd. Office : 215, Rewa Chambers, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai - 400 020. All India Federation Tel.: 022-2200 6342 / 63 / 4970 6343 of Tax Practitioners E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.aiftponline.org | i | | Palkhivala – Tribute | © All India Federation of Tax Practitioners 1st Edition : January 2021 DISCLAIMER Disclaimer The contents of this publication are solely for educational purposes. It does not constitute professional advice or formal documentation. While due care and sincere efforts has been made in preparing this digest to avoid errors or omissions, the existence of mistakes and omissions not ruled out. Any mistake. error or discrepancy may be brought to the notice. Neither the members of the research team, editorial team nor the All India Federation of Tax Practitioners (AIFTP) accepts any liabilities. No part of this publication should be distributed or copied for commercial use, without express written permission from the AIFTP. All disputes are subject to Mumbai Jurisdiction. Published by Dr. K. Shivaram, Senior Advocate for All India Federation of Tax Practitioners, 215, Rewa Chambers, 2nd Floor, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai–400 020. -

University Court List -05.09.2014 UNIVERSITY of DELHI STATUTE

University Court List -05.09.2014 UNIVERSITY OF DELHI STATUTE 2(1)(i) STATUTE 2(1)(vii) 1. Hon’ble Mohd. Hamid Ansari 7. Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Chancellor Treasurer University of Delhi University of Delhi Vice-President of India Delhi-110007 New Delhi – 110001 STATUTE 2(1)(viii) STATUTE 2(1)(ii) 8. Prof. Upendra Baxi 2. Justice Rajendra Mal Lodha A-51, Law Apartments (Pro-Chancellor, University of Delhi) Karkardoma Chief Justice of India Delhi-110092 Supreme Court of India New Delhi-110001 9. Prof. Vrajendra Raj Mehta 5928,DLF Qutab Enclave STATUTE 2(1)(iii) Phase-IV Gurgaon - 122002. 3. Prof. Dinesh Singh Vice-Chancellor 10. Prof. Deepak Nayyar University of Delhi 5-B, Friends Colony (West) Delhi-110007 New Delhi -110065 STATUTE 2(1)(iv) 11. Prof. Deepak Pental Q.No. 7, Ty.V-B, 4. Prof. Sudhish Pachauri South Campus, Pro-Vice Chancellor New Delhi-110021. University of Delhi Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(ix) 12. Dr. S.C. Jindal (Offg.) STATUTE 2(1)(v) Librarian 5. Prof. Malashri Lal University of Delhi Dean of Colleges Delhi-110007 University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(x) 13. Prof.(Ms.) Satwanti Kapoor Proctor STATUTE 2(1)(vi) University of Delhi Delhi-110007 6. Prof. Umesh Rai Director STATUTE 2(1)(xi) University of Delhi South Campus Benito Jaurez Road 14. Prof. J.M. Khurana New Delhi-110021 Dean Student’s Welfare University of Delhi Delhi-110007 Contd. p/2 1 STATUTE 2(1)(xii) 23. The Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies 15. The Head University of Delhi Department of English Delhi-110007.