12.2% 122,000 135M Top 1% 154 4,800

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

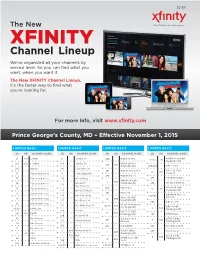

XFINITY Channel Lineup We’Ve Organized All Your Channels by Service Level

2C-307 The New XFINITY Channel Lineup We’ve organized all your channels by service level. So you can find what you want, when you want it. The New XFINITY Channel Lineup. It’s the faster way to find what you’re looking for. For more info, visit www.xfinity.com Prince George’s County, MD – Efective November 1, 2015 LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME WMDO-47 (uniMàs) 24 941 C-SPAN 23 Jewelry TV 200 WDCA Movies! 15/563 795 Washington DC WDCA-20 (MY) 104 942 C-SPAN2 184 Jewelry TV 20 810 Washington DC 269/559 WMPT V-me 287 Daystar 190 Leased Access WMPT-22 (PBS) 201 WDCW Antenna TV 22 812 72 Educational Access 76 Local Origination Annapolis 206 WDCW This TV 73 Educational Access 279 MHz Arirang 275 WNVC Bon-China WDCW-50 (CW) 3 803 MHz CCTV Washington DC 294 The Word Network 74 Educational Access 276 Documentary WPXW-66 (ION) 75 Educational Access 266 WETA Kids 16 813 273 MHz CCTV News Washington DC 265 WETA UK 77 Educational Access WQAW-20 (Azteca 278 MHz CNC World 198/568 WETA-26 (PBS) America) 78 Educational Access 26 800 277 MHz France 24 Washington DC 208 WRC Cozi TV 96 Educational Access WFDC-14 (Univision) 272 MHz NHK World TV 14/561 794 WRC-4 (NBC) Washington DC 4 804 89/283 EVINE Live Washington DC 274 MHz RT WHUT-32 (PBS) 19 802 291 799 EWTN Washington DC 197 WTTG Buzzr 280 MHz teleSUR 69 Gov’t Access WJLA Live Well WTTG-5 (FOX) 205 5 805 271 MHz Worldview Network Washington DC 70 Gov’t Access 268 MPT2 204 WJLA MeTV 207 WUSA Bounce TV 71 -

American Home Systems V. Cambria Homeowners Association : Brief of Appellant Utah Court of Appeals

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Court of Appeals Briefs 2011 American Home Systems v. Cambria Homeowners Association : Brief of Appellant Utah Court of Appeals Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca3 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Court of Appeals; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. Cole Cannon; Cannon Law Group, PLLC; Attorney for Appellee. Justin D. Heideman; Travis Larsen; Heideman, McKay, Heugly & Olsen, L.L.C; Attorneys for Appellant. Recommended Citation Brief of Appellant, American Home Systems v. Cambria Homeowners Association, No. 20111085 (Utah Court of Appeals, 2011). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca3/3015 This Brief of Appellant is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Court of Appeals Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. IN THE UTAH COURT OF APPEALS SYSTEMS, LLC, dba rporation, Counterclaim , and Appellant, Case No. 20111085 OWNERS Utah non-profit |, Counterclaimant, ee. ORDER OF CONFIRMATION OF ARBITRAL AWARD THE HONORABLE JUDGE MCVEY FOURTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT AND FOR UTAH COUNTY, STATE OF UTAH BRIEF OF APPELLANT JUSTIN D. HEIDEMAN (USB #8897) TRAVIS LARSEN (USB #11697) HEIDEMAN, MCKAY, HEUGLY & OLSEN, L.L.C. 2696 North University Avenue, Suite 180 Provo, Utah 84604 Association, Telephone: (801) 812-1000 iheideman@hmho-law. -

XFINITY CHANNEL LINEUP We’Ve Organized All Your Channels by Service Level

5C-307 THE NEW XFINITY CHANNEL LINEUP We’ve organized all your channels by service level. So you can nd what you want, when you want it. The New XFINITY Channel Lineup. It’s the faster way to nd what you’re looking for. For more info, visit www.x nity.com Baltimore City – Eff ective August 1, 2014 265 WETA UK 48/118 834 Esquire LIMITED BASIC 26 800 WETA-26 (PBS) Washington EXPANDED BASIC 799 EWTN DC 47 839 Food Network SD HD SD HD 11/561 WFDC-14 (Univision) 106 821 Fox Business Network 16 941 C-SPAN 35 831 A&E Washington DC 61 820 Fox News 104 942 C-SPAN2 10 881 ABC Family 78 900 WGN America 729 857 Fox Sports 1 287 Daystar 27/138 889 AMC 19 807 WHUT-32 (PBS) Washington 32 824 FX 185 DoD News DC 40 868 Animal Planet 725 842 FXX 77 Educational Access 23 813 WJZ-13 (CBS) Baltimore 114 930 BBC America 115 874 fyi, 291 799 EWTN 204 WMAR Live Well 65 866 BET 3 849 Golf Channel 25 Gov’t Access 12 802 WMAR-2 (ABC) Baltimore 103 814 Bloomberg TV 179 924 GSN 18 808 HSN 563 WMDO-47 (uniMàs) 29 832 Bravo 116 876 H2 295 Inspiration Network Washington DC 941 C-SPAN 54 830 Hallmark 20/286 ION 269/559 WMPT V-me 942 C-SPAN2 157 894 Hallmark Movie Channel 50/184 Jewelry TV 22 812 WMPT-22 (PBS) Annapolis 105 C-SPAN3 57 816 Headline News 190 Leased Access 14 804 WNUV-54 (CW) Baltimore 42 878 Cartoon Network 46 838 HGTV 268 MPT2 294 The Word Network 297 The Church Channel 37 875 History Channel 75/76 Public Access 198/568 WQAW-20 (Azteca America) 58 819 CNBC 808 HSN 13 806 QVC 203 WUTB Bounce TV 56 817 CNN 88 HSN2 89/283 ShopHQ 24 803 WUTB-24 (MY) Baltimore -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Monongalia County, W. Va. and Preston ) MB Docket No. 12-1 County, W. Va. ) CSR-_____________ ) Petition for Special Relief for ) Modification of the Television Market of ) Station WBOY-TV with Respect to ) DISH Network and DIRECTV ) ) To: Chief, Media Bureau ) PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF Edward Hawkins Monongalia County Commission 243 High Street, Room 202 Morgantown, WV 26505 Craig Jennings Commissioner Preston County 106 W Main St #202 Kingwood, WV 26537 September 25, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY. ................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 3 A. Congress Intended the STELAR Satellite Market Modification Process to Rectify “Orphan County” Situations like Monongalia and Preston Counties ......................................... 3 III. WBOY-TV MEETS THE STATUTORY TEST FOR MARKET MODIFICATION ....... 5 A. Carriage of WBOY-TV is Technically and Economically Feasible for DIRECTV and DISH Network ............................................................................................................................ 5 B. Factor 1: Historic Carriage of WBOY-TV Enhances the Weight in Favor of the Petition 5 C. Factor 2: WBOY-TV Provides Extensive Local Programming to the Counties ............. 5 D. Factor 3: Adding the Counties to WBOY-TV’s Local Market Will Increase -

T.V Channel Guide

Channel Lineup Effective December 11, 2020 1-800-xfinity | xfinity.com Summit Co. Blue River, Breckenridge, Dillon, Frisco, Keystone, Silverthorne, Summit County LIMITED BASIC 644,1053 KETD HD 507 Hallmark Movies & 48 USA Network 681,1484 Food Network HD 2 KWGN (CW) 646,1025 KDEN HD (TEL) Mysteries 49 Lifetime 688,1411 Syfy HD 3 KCDO (IND) 648,1059 KPXC HD (ION) 672,1223 Golf Channel HD 50 FX 689,1207 NBC Sports 4 KCNC (CBS) 652,1007 KMGH HD (ABC) 674,1473 National 51 Comedy Central Network HD 5 KTVD (MyTV) 653,1009 KUSA HD (NBC) Geographic HD 52 NBC Sports Network 691,1409 FX HD 6 KRMA (PBS) 654,1004 KCNC HD (CBS) 675,1402 A&E HD 54 Oxygen 692,1410 FXX HD 7 KMGH (ABC) 655,1031 KDVR HD (FOX) 688,1411 Syfy HD 55 TNT 699,1450 TLC HD 8,1028 K28HI (IND) 656,1033 KQCK HD 689,1207 NBC Sports 56 Food Network 723,1606 MTV HD 9 KUSA (NBC) 660,1012 KBDI HD (PBS) Network HD 57 AMC 724,1403 USA Network HD 10,22,165 Government 701,1006 KRMA HD (PBS) 692,1410 FXX HD 59 BET 728,1728 Nickelodeon HD Access 702,1002 KWGN HD (CW) 724,1403 USA Network HD 60 MTV 730,1471 Animal Planet HD 11 KPXC (ION) 703,1014 KTFD HD (UNV) 730,1471 Animal Planet HD 61 VH1 731,1734 Cartoon 12 KBDI-DT (PBS) 704,1020 KTVD HD (MyTV) 735,1477 Smithsonian 62,1426 TV Land Network HD 13 KDVR (FOX) 705,1003 KCDO HD (IND) Channel HD 63 TBS 736,1478 HISTORY HD 14 KTFD (UMAS) 706,1050 KCEC HD (UMAS) 736,1478 HISTORY HD 64 The Weather Channel 737,1112 HLN HD 16,1016 K26GY (IND) 716,1449 Discovery HD 738,1111 CNN HD 65 Travel Channel 738,1111 CNN HD 18 HSN 717,1010 QVC2 HD2 742,1110 FOX -

21DLTDC COL 04R1.Qxd (Page 1)

DLD‰‰†‰KDLD‰‰†‰DLD‰‰†‰MDLD‰‰†‰C 4 LEISURE DELHI TIMES, THE TIMES OF INDIA MONDAY 21 APRIL 2003 DAILY CROSSWORD BELIEVE IT OR NOT TELEVISION tvguide.indiatimes.com CINEMA DD I 2130 Kahani Terii Merii 1400 Non-Stop Hits 2003: WI vs. Aus, ENGLISH FILMS Pawan (G’bad); EK AUR EK GYARAH: (Sanjay Dutt, BOL TARA BOL Govinda,Amrita Arora) DT 2200 Achanak 37 Saal 1500 Loveline 2nd Test, Day 4, CATCH ME IF YOU CAN (A): (Tom Hanks, Leonar- 0800 Subah Savere Cinemas (3.10 & 10.15 Shelly von Strunkel 0830 World View India: Baad 1530 Start Session 1, LIVE do Di Caprio, Martin Sheen, Amy Adams) PVR p.m.), Delite, Rachna, 1600 Select 2135 Sportscenter Hindi Saket (12.10 & 11.30 p.m.), PVR Naraina (1.10 & M2K (Rohini) (12.45, 3.45 Crisis in Iraq SAHARA TV 10 p.m.); CHICAGO (A): (Cathrine Zeta-Jones, Re- ARIES (March 21 - April 19) After weeks of 0902 Iraq War - Panel 1700 Non Stop Hits LIVE & 10.20 p.m.), PVR having to play it cool in certain important sit- 0830 Manpasand 1800 No- Stop Mega Hits 2205 Aus Tour of WI 2003: nee Zellweger & Richard Gere) PVR Saket (1 & Naraina (4.10, 7.15 & Discussion 0930 Just Kids 7.10 p.m.), PVR Naraina (3.50 & 7.50 p.m.), Priya uations, at long last Venus enters Aries. This 1000 News in Sanskrit 1900 Ek Do Teen WI vs. Aus, 2nd 10.20 p.m.), PVR both increases your charm and improves your 1030 Hello 2015 Start (8.15 p.m. -

Channel Lineup

† † 50 Comedy Central 124 Teen Nick 191 Hallmark Channel 376 5 StarMAX Ossining/ † † 51 E! 125 Boomerang 192 SundanceTV 377 OuterMAX † † Rockland County 52 VH1 126 Disney Junior 193 Hallmark Movie Channel 378 Cinemax West † † February 2014 53 MTV 127 Sprout 195 MTV Tr3s 379 TMC On Demand † 54 BET 131 Kids Thirteen 196 FOX Deportes 380 TMC Xtra 2 WCBS (2) New York (CBS) 2† 55 MTV2 132 WLIW World 197 mun 381 TMC West 3 WPXN (31) New York (ION) 57 Animal Planet 133 WLIW Create 198 Galavisión 382 TMC Xtra West 4 WNBC (4) New York (NBC) † † 58 truTV 135 EWTN 199 Vme 400-413 Optimum Sports & 5 WNYW (5) New York (FOX) † 6 WXTV (41) Paterson 59 CNN Headline News 136 Daystar 291 The Jewish Channel On Demand Entertainment Pak 60 SportsNet New York 414 Sports Overflow (Univisión)† 137 Telecare 300 HBO On Demand † 61 News 12 Traffic & Weather 138 Shalom TV 301 HBO Signature 415-429 Seasonal Sports Packages 7 WABC (7) New York (ABC) 62 The Weather Channel 140 ESPN Classic 302 HBO Family 430 NBA TV 8 NJTV † † 64 Esquire Network 141 ESPNEWS 303 HBO Comedy 432-450 Seasonal Sports Packages 9 My9 New York (MNT-WWOR) † 65 C-SPAN 142 FXX 304 HBO Zone 460 Sports Overflow 2 10 Trinity Broadcasting Network 66 C-SPAN 2 143 CBS Sports Network 305 HBO Latino 461-465 Optimum Sports & 11 WPIX (11) New York (CW) † † † 67 Turner Classic Movies 144 ESPNU 306 HBO West Entertainment Pak 12 News 12 Hudson Valley † † 68 Syfy 145 The Golf Channel 307 HBO2 West 470-477 Barclay’s Premier League 13 WNET (13) New York (PBS) Channel Lineup Channel 70 YES Network 146 NBC Sports -

Cinema of India - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Cinema of India - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_film Cinema of India From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Indian film) The cinema of India consists of films produced across India, including the cinematic culture of Mumbai along with the cinematic traditions of states such as Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Karnataka, Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Indian films came to be followed throughout South Asia and the Middle East. As cinema as a medium gained popularity in the country as many as 1,000 films in various languages of India were produced annually. Expatriates in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States continued to give rise to international audiences for Hindi-language films. Devi in the 1929 film, Prapancha Pasha (A Throw of Dice), directed by Franz Osten.jpg|thumb|Charu Roy and Seeta Devi in the 1929 film, Prapancha Pash . In the 20th century, Indian cinema, along with the American and Chinese film industries, became a global enterprise. [1] Enhanced technology paved the way for upgradation from established cinematic norms of delivering product, radically altering the manner in which content reached the target audience. [1] Indian cinema found markets in over 90 countries where films from India are screened. [2] The country also participated in international film festivals especially satyajith ray(bengali),Adoor Gopal krishnan,Shaji n karun(malayalam) . [2] Indian filmmakers such as Shekhar Kapur, Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta etc. found success overseas. [3] The Indian government extended film delegations to foreign countries such as the United States of America and Japan while the country's Film Producers Guild sent similar missions through Europe. -

Channel Guide for Cable TV and XFINITY on Campus at Towson University These Channels Are Viewable with a Cable Ready Digital Television

Channel Guide for Cable TV and XFINITY On Campus at Towson University These channels are viewable with a cable ready digital television. Your TV must be set to “Cable” and you must first scan for channels. See your TV owner’s manual for more information. If you need assistance, call Student Computing Services at 410-704-5151 (options 1,0). All of these channels are also available through XFINITY On Campus (except WMJF, XTSR and mtvU). Channels marked TV GO are available off campus via xfinityoncampus.com and its apps. Channel Network TV GO Channel Network TV GO Channel Network TV GO 6.1 Program Guide 34.1 Big Ten Network TV GO 63.1 WZDC - (Telemundo, Washington) 7.1 Fox News TV GO 35.1 BBC America TV GO 64.1 WMDO - (UniMas, Washington) 8.1 CNN TV GO 36.1 ID TV GO 65.1 WQAW - (Azteca, Washington) 9.1 HLN TV GO 37.1 Universal HD 66.1 WFDC - (Univision, Washington) 10.1 MSNBC TV GO 38.1 Velocity TV GO 69.1 WMJF - (ARTS / Towson University) 11.1 The Weather Channel TV GO 39.1 Discovery 69.2 XTSR TU Student Radio 12.1 CNBC TV GO 40.1 Animal Planet TV GO 69.3 mtvU 13.1 Bloomberg 41.1 History TV GO 70.1 UP TV GO 14.1 WMAR-2 (ABC, Baltimore) 42.1 Viceland TV GO 71.1 Sprout TV GO 15.1 WBAL-11 (NBC, Baltimore) 43.1 The Food Network TV GO 72.1 Disney TV GO 16.1 WJZ-13 (CBS, Baltimore) 44.1 The Travel Channel TV GO 73.1 Nick 17.1 WNUV-54 (CW, Baltimore) 45.1 HGTV TV GO 74.1 Cartoon Network TV GO 18.1 WBFF-45 (Fox, Baltimore) 46.1 Lifetime TV GO 75.1 Freeform 19.1 WHUT-32 (PBS, Washington) 47.1 Hallmark TV GO 76.1 EWTN TV GO 20.1 WMPT-67 (PBS, Baltimore) -

International Programming

International Programming Arabic Ch. Ch. Colors Bangla 779 Phoenix InfoNews 9918 614.03 MTV Hindi 718 Aastha 719 Arabica 9876 628.07 LAFF TV 237 Impact Television 268 Marathi Ch. Ch. Aghapy 9880 628.39 Maasranga 793 Phoenix North America 9919 614.04 NDTV 24x7 723 Adithya TV 762 B4U Music 716 716 Link TV 9410 In Country Television 230 Aastha 719 719 Al Arabiya 639 NTV Bangla 790 Shen Zhen TV 9935 614.19 NDTV Good Times 724 Jaya Max 759 euronews 9793 600.04 Mercury TV (Mall) 86 INSP 259 Colors Marathi 9906 620.01 Al Hayah 1 647 Willow Cricket 712 TVB Chinese 9938 614.28 News 18 India 711 Jaya Plus 760 FOX Sports 1 150 150 HD HD NASA Television 286 Jewelry Television 83 Zee Marathi 9905 620.02 Al Jazeera 638 Willow Xtra 722 TVB Drama 9939 614.27 Rishtey 699 Jaya TV 755 Golf Channel 401 401 HD HD NDTV 24x7 723 Justice Network 252 Al Jazeera Mubasher 672 Zee Bangla 776 Zhejiang TV 9937 614.21 Rishtey Cineplex 730 JMovies 763 MTV Hindi 718 718 Polish Ch. Ch. News18 711 Kids and Teens TV (KTV) 264 Al Quran Al Karim 9877 628.17 SAB 701 Kalaignar 758 NDTV 24x7 723 723 Bengali Ch. Ch. Cricket Ch. Ch. Baby TV Polish 9888 611.06 Pursuit 393 LAFF TV 237 Al Yawm 646 Sahara One 702 KTV 757 Tennis Channel 400 400 HD QVC 71 Link TV 9410 Aastha 719 Willow Cricket 712 euronews 9793 600.04 Arabica 9876 628.07 HD Sahara Samay 707 Sirippoli 756 Trace Urban 9861 608.05 QVC2 137 Mercury TV (Mall) 86 Colors Bangla 779 iTVN 9884 611.02 ART Aflam 1 633 Willow Xtra HD 722 Sanskar 721 Star Vijay 754 Real 94 NASA Television 286 Sangeet Bangla 780 iTVN HD 9894 611.02 World ART Aflam 2 634 SET 695 Sun Music 761 Filipino Ch. -

Channel Lineup Effective January 17, 2020 1-800-Xfinity | Xfinity.Com

Channel Lineup Effective January 17, 2020 1-800-xfinity | xfinity.com Seattle City of Seattle, City of Edmonds, City of Lake Forest Park, City of Shoreline, City of Woodway, Vashon Island LIMITED BASIC 331,1168 KING Justice 401 FXX 53 FX 656,1123 FOX Business 3 KWPX (ION) Network 480,1627 ASPiRE 54 TNT Network HD 4 KOMO (ABC) 334,1150 KBTC MHZ 500 Hallmark Movies & 55 TBS 657,1111 CNN HD 5 KING (NBC) Worldview (PBS) Mysteries 56 BET 658,1121 CNBC HD 6 KONG (IND) 336,1155 KCTS Create 618,1410 FXX HD 58 USA Network 659,1122 Bloomberg TV HD 7 KIRO (CBS) (PBS) 620,1208 FOX Sports 1 HD 59 Syfy 661,1113 MSNBC HD 8 Discovery 337,1156 KCTS Kids 625,1223 Golf Channel HD 60 Comedy Central 662,1404 TNT HD 9 KCTS (PBS) 338,1157 KCTS World (PBS) 626,1207 NBC Sports 62 VH1 663,1243 MotorTrend 10 KZJO (MyTV) 340,1192 KZJO AntennaTV Network HD 63 MTV Network 11 KSTW (CW) 343,1188 KVOS Movies! 647,1418 BBC America HD 64,1639 MTV2 664,1434 TBS HD 12 KBTC (PBS) 347,1195 KFFV Decades 651,1466 E! HD 65 E! 665,1409 FX HD 13 KCPQ (FOX) 355,1180 KSTW Start TV 652,1463 Bravo HD 66 Bravo 667,1471 Animal Planet HD 14 KBCB (IND) 357,1159 KCPQ CourtTV 653,1455 Lifetime HD 67 AMC 669,1450 TLC HD 15 KFFV (MyTV) 358,1158 KCPQ (Mystery 655,1110 FOX News 68 HGTV 670,1402 A&E HD 16 QVC TV) Channel HD 70 Golf Channel 671,1478 HISTORY HD 17 HSN 599 Xfinity Latino 656,1123 FOX Business 71 Oxygen 672,1403 USA Network HD 18,234,1056 KWDK (DAY) Entertainment Channel Network HD 118 Universal Kids 673,1473 National 19 Hallmark Channel 619,1029 CBUT HD 657,1111 CNN HD 128,1420 WGN -

Being Salman the Dangerous Innocence of Bollywood’S Most Controversial Superstar Anna Mm Vetticad

Founder: Vishva Nath (1917-2002) VOLUME 09 • ISSUE 11 Editor-in-Chief, Publisher & Printer: Paresh Nath NOVEMBER 2017 cover story 20 Being Salman The dangerous innocence of Bollywood’s most controversial superstar anna mm vetticad Salman Khan has appeared in some of the biggest blockbusters in Hindi film history. But his career has been blighted by allegations of involvement in crimes of poaching, domestic violence and culpable homicide. In the last decade, the star has tried to reform his image. If he has succeeded to some extent, it has been not just through his own efforts, but also the willingness of his fans and many around him to accept or justify even his most disturbing behaviour. 20 perspectives 17 48 62 politics 14 Hammer and Fickle 48 The Second Coming Nepali politics sees a major reconfiguration How Malayalam cinema’s only female superstar got back to work in time for a watershed election leena gita reghunath shubhanga pandey 62 Director’s Cut 17 Counting Crores The cinematic myth-making of Louis Mountbatten Why Indian films’ box-office figures do not add up manik sharma suprateek chatterjee NOVEMBER 2017 3 the lede 72 12 arts 8 People’s Choice Attendance and absence at the Tibetan photo essay / health Music Awards 72 Deadly Risk aathira konikkara Unsafe abortions through the ages politics laia abril 12 Driving Miss Jinnah An antique car exhibit in Karachi spotlights an underappreciated historical figure alizeh kohari books 94 literature 86 The Streets of Desire Old Delhi’s subversive love-letter manuals kanupriya dhingra 86 the bookshelf 92 showcase 94 NOTE TO READERS: “A MARKETING INITIATIVE” ON PAGES 42–46 AND “SPONSORED FEATURE” ON editor’s pick 98 PAGES 60–61 AND 70–71 ARE PAID ADVERTISING CONTENT.