Great Outing, Even Greater People in Sandy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Vs. Philadelphia Phillies (36-63) July 25, 2015

CHICAGO CUBS (51-45) VS. PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (36-63) JULY 25, 2015 LINESCORE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E LOB Phillies 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 2 0 5 11 0 10 Cubs 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 Winning Pitcher: Hamels (6-7) Losing Pitcher: Arrieta (11-6) Save: None STARTING PITCHERS GAME INFORMATION Pitcher IP H R ER BB SO WP HR PC/S Left Time of Game: 2:38 Cole Hamels (W) 9.0 0 0 0 2 13 0 0 129/83 --- First Pitch: 3:05 PM Jake Arrieta (L) 6.0 6 3 3 3 8 0 1 94/58 0-3 Temperature: 80 degrees Courtesy of Stats, Inc. Wind: E 14 mph HOME RUNS ATTENDANCE Team Batter No. Pitcher Inn. Count Men On Location Today: 41,683 PHI Howard 17 Arrieta 3 1-0 2 Left-Center Field Season Total: 1,648,259 # of Wrigley Dates: 47 (25-22) Average per Date: 35,069 CHICAGO CUBS The Cubs were no-hit for the first time since September 9, 1965, a perfect game by the Dodgers Sandy Koufax at Dodger Stadium ... this is the first time the Cubs have been no-hit at Wrigley field since August 19, 1965 (gm. 1) vs. the Reds Jim Maloney ... today snapped a major league record 7,920 consecutive games (of at least nine innings) with at least one hit ... the Cubs had gone 49 full seasons without being no-hit, the longest span in major league history. -

The Last Innocents: the Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers Online

rck87 (Get free) The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers Online [rck87.ebook] The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers Pdf Free Michael Leahy ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook #120314 in Books Michael Leahy 2016-05-10 2016-05-10Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x 1.49 x 6.00l, .0 #File Name: 0062360566496 pagesThe Last Innocents The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers | File size: 71.Mb Michael Leahy : The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers: 29 of 31 people found the following review helpful. SHAQ GOLDSTEIN SAYS: 1960rsquo;S DODGERShellip; UNDER THE MICROSCOPE.. ONhellip; hellip; OFF THE FIELD. A GROWN UP KID OF THE 60rsquo;S DREAM COME TRUEBy Rick Shaq GoldsteinAs a child born in New York to a family that lived and died with the Brooklyn Dodgershellip; ldquo;Dem Bumsrdquo; were my lifehellip; and lo and behold when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles after the 1957 seasonhellip; my family moved right along with them. So the time period covered in this amazinghellip; detailedhellip; no holds barredhellip; story of the 1960rsquo;s era Los Angeles Dodgershellip; is now being read and reviewed by a Grandfatherhellip; who as a kidhellip; not only went to at least one-hundred games at the L.A. -

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ........................... -

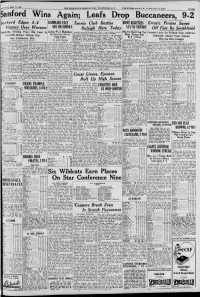

1947-05-17 [P

Sanford Wins Again; Leafs Drop Buccaneers, 9-2 Sanford Edges 5-4 RAMBLERS FACE Tennis Club Battles ROWE REGISTERS Erratic Pirates Swept Victory Over Warsaw SOX ON SUNDAY Raleigh Here Today SIXTH VICTORY Off Feet By Smithfield Nessing Prove Big Guns In Jackets Play Bladenboro Raleigh’s powerful Eastern Caro- Here is an unofficial tentative Phil Vet Hasn’t Lost Yet; Corsairs On Nesselrode, lina Tenhis association netters col- lineup of today's matches: Carry Without Nate Andrews; In Eastern State court Mates Trounce Powerful Spinner Clin- lide with the new Wilmington Bob Andrew* vs. Bill Weathers, Reds Attack; on the Robert Poklemba Absent From Game Today aggregation today Horace Emerson vs. Ed Cloyle, By 8 4 Score Lineup; ton, Lumberton Win Strange clay courts at 3:00 p.m. Rev. Walter Freed vs. High If necessary, some matches will Kiger, Leslie Boney, Jr., vs. C. R. Play Sox Here BY JIGGS POWERS CINCINNATI, May 16.— {#) — Tonight take place on the asphalt at Green- Council, Gene Fonvielle vs. Father Joe Ness- Back by a 15-hit Nesselrode and While both and Two are booked in the field Lake. John Sloan vs. M. attack, Schoolboy j *fink Sanford Warsaw games Dillon, Jimmy Smithfield-Selma's Leafs sliced a that carried run Rowe boasted his sixth consecu- single in Eames. one-two home were the male side of Wil- W. in the men’s their Sanford’s battling it out, Lumberton Eastern State League for the com- Although Stubbs, singles. two-game series with the Wil- Benton, the out the star once tive victory, without a to- pitcher, grounded clayed roles waltzed to a mington tennis has proven slightly Other matches may be arranged. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

MEDIA and LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS of LATINOS in BASEBALL and BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of T

MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Mihir Parekh 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to my supervisor, Dr. William Arcé, whose knowledge and expertise in Latino studies were vital to this project. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Timothy Morris and Dr. James Warren, for the assistance they provided at all levels of this undertaking. Their wealth of knowledge in the realm of sport literature was invaluable. To my family: the gratitude I have for what you all have provided me cannot be expressed on this page alone. Without your love, encouragement, and support, I would not be where I am today. Thank you for all you have sacrificed for me. April 22, 2015 iii Abstract MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION Mihir D. Parekh, MA The University of Texas at Arlington, 2015 Supervising Professors: William Arcé, Timothy Morris, James Warren The first chapter of this project looks at media representations of two Mexican- born baseball players—Fernando Valenzuela and Teodoro “Teddy” Higuera—pitchers who made their big league debuts in the 1980s and garnered significant attention due to their stellar play and ethnic backgrounds. Chapter one looks at U.S. media narratives of these Mexican baseball players and their focus on these foreign athletes’ bodies when presenting them the American public, arguing that 1980s U.S. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

1960-63 Post Cereal Baseball Card .Pdf Checklist

1960 Post Cereal Box Panels Mickey Mantle Don Drysdale Al Kaline Harmon Killebrew Eddie Mathews Bob Cousy Bob Pettit Johnny Unitas Frank Gifford 1961 Post Cereal Baseball Card Checklist 1 Yogi Berra (Hand Cut) 1 Yogi Berra (Perforated) 2 Elston Howard (Hand Cut) 2 Elston Howard (Perforated) 3 Bill Skowron (Hand Cut) 3 Bill Skowron (Perforated) 4 Mickey Mantle (Hand Cut) 4 Mickey Mantle (Perforated) 5 Bob Turley (Hand Cut) 5 Bob Turley (Perforated) 6 Whitey Ford (Hand Cut) 6 Whitey Ford (Perforated) 7 Roger Maris (Hand Cut) 7 Roger Maris (Perforated) 8 Bobby Richardson (Hand Cut) 8 Bobby Richardson (Perforated) 9 Tony Kubek (Hand Cut) 9 Tony Kubek (Perforated) 10 Gil McDougald (Hand Cut) 10 Gil McDougald (Perforated) 11 Cletis Boyer (Hand Cut) 12 Hector Lopez (Hand Cut) 12 Hector Lopez (Perforated) 13 Bob Cerv (Hand Cut) 14 Ryne Duren (Hand Cut) 15 Bobby Shantz (Hand Cut) 16 Art Ditmar (Hand Cut) 17 Jim Coates (Hand Cut) 18 John Blanchard (Hand Cut) Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 19 Luis Aparicio (Hand Cut) 19 Luis Aparicio (Perforated) 20 Nelson Fox (Hand Cut) 20 Nelson Fox (Perforated) 21 Bill Pierce (Hand Cut) 21 Bill Pierce (Perforated) 22 Early Wynn (Hand Cut) 22 Early Wynn (Perforated) 23 Bob Shaw (Hand Cut) 24 Al Smith (Hand Cut) 24 Al Smith (Perforated) 25 Minnie Minoso (Hand Cut) 25 Minnie Minoso (Perforated) 26 Roy Sievers (Hand Cut) 26 Roy Sievers (Perforated) 27 Jim Landis (Hand Cut) 27 Jim Landis (Perforated) 28 Sherman Lollar (Hand Cut) 28 Sherman Lollar (Perforated) 29 Gerry Staley (Hand Cut) 30 Gene Freese -

Vs. Philadelphia Phillies (25-17) Game No

St. Louis Cardinals (24-18) vs. Philadelphia Phillies (25-17) Game No. 43 • Home Game No. 22 • Busch Stadium • Saturday, May 19, 2018 RHP John Gant (1-1, 4.15) vs. RHP Zach Eflin (1-0, 0.71) RECENT REDBIRDS: The Cardinals tallied a season-best 15 hits and blasted RECORD BREAKDOWN three home runs for a 12-4 win over the Phillies last night to knot the four-game CARDINALS vs. PHILLIES All-Time Overall ...........9,983-9,504 series...Francisco Peña and José Martínez each finished a triple short of the All-Time (1892-2018):......................... 1,230-963 Under Mike Matheny .........568-446 cycle...St. Louis begins the day in 3rd place in the N.L. Central, 1.5 games back in St. Louis (1892-2018): .............................. 655-443 2018 Overall ............................24-18 of Milwaukee (the top four teams in the NL Central Division all sport 18 losses)... at Sportsman’s/Robison Fld (1892-1920) .... 119-144 the Cardinals +24 run differential is 6th-best in the Senior Circuit. Busch Stadium .........................13-8 at Sportsman’s Park/Busch I (1920-66) ...... 346-153 On the Road ............................ 11-10 FARING WELL AGAINST PHILLY: St. Louis is 16-6 against the Phillies since at Busch Stadium II (1966-2005) ................. 163-123 Day ............................................11-8 2015, which includes a 10-3 record at Busch Stadium...St. Louis’ .727 win per- at Busch Stadium III (2006-18) ................27-23 Night ........................................ 13-10 centage vs. Philadelphia over that stretch is its highest against any opponent in Philadelphia (1892-2017) .......................... 575-520 Spring...................................17-13-2 (min.