Revisiting the Politics of Belonging in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

206 Villages Burnt in the North West and South West Regions

CHRDA Email: [email protected] Website: www.chrda.org Cameroon: The Anglophone Crisis 206 Villages burnt in the North West and South West Regions April 2019 SUMMARY The Center for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA) has analyzed data from local sources and identified 206 villages that have been partially, or completely burnt since the beginning of the immediate crisis in the Anglophone regions. Cameroon is a nation sliding into civil war in Africa. In 2016, English- speaking lawyers, teachers, students and civil society expressed “This act of burning legitimate grievances to the Cameroonian government. Peaceful protests villages is in breach of subsequently turned deadly following governments actions to prevent classical common the expression of speech and assembly. Government forces shot peaceful article 3 to the Four protesters, wounded many and killed several. Geneva Convention 1949 and the To the dismay of the national, regional and international communities, Additional Protocol II the Cameroon government began arresting activists and leaders to the same including CHRDA’s Founder and CEO, Barrister Agbor Balla, the then Convention dealing President of the now banned Anglophone Consortium. Internet was shut with the non- down for three months and all forms of dissent were stifled, forcing international conflicts. hundreds into exile. Also, the burning of In August 2017, President Paul Biya of Cameroon ordered the release of villages is in breach of several detainees, but avoided dialogue, prompting mass protests in national and September 2017 with an estimated 500,000 people on the streets of international human various cities, towns and villages. The government’s response was a rights norms and the brutal crackdown which led to a declaration of independence on October host of other laws” 1, 2017. -

SSA Infographic

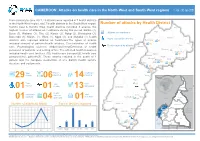

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

Programming of Public Contracts Awards and Execution for the 2020

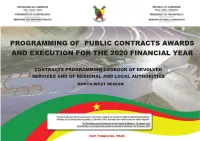

PROGRAMMING OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS AWARDS AND EXECUTION FOR THE 2020 FINANCIAL YEAR CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING LOGBOOK OF DEVOLVED SERVICES AND OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES NORTH-WEST REGION 2021 FINANCIAL YEAR SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of No Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts No. page contracts REGIONAL 1 External Services 9 514 047 000 3 6 Bamenda City Council 13 1 391 000 000 4 Boyo Division 9 Belo Council 8 233 156 555 5 10 Fonfuka Council 10 186 760 000 6 11 Fundong Council 8 203 050 000 7 12 Njinikom Council 10 267 760 000 8 TOTAL 36 890 726 555 Bui Division 13 External Services 3 151 484 000 9 14 Elak-Oku Council 6 176 050 000 9 15 Jakiri Council 10 266 600 000 10 16 Kumbo Council 5 188 050 000 11 17 Mbiame Council 6 189 050 000 11 18 Nkor Noni Council 9 253 710 000 12 19 Nkum Council 8 295 760 002 13 TOTAL 47 1 520 704 002 Donga Mantung Division 20 External Services 1 22 000 000 14 21 Ako Council 8 205 128 308 14 22 Misaje Council 9 226 710 000 15 23 Ndu Council 6 191 999 998 16 24 Nkambe Council 14 257 100 000 16 25 Nwa Council 10 274 745 452 18 TOTAL 48 1 177 683 758 Menchum Division 27 Furu Awa Council 4 221 710 000 19 28 Benakuma Council 9 258 760 000 19 29 Wum Council 7 205 735 000 20 30 Zhoa Council 5 184 550 000 21 TOTAL 25 870 755 000 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 37 SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of No Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts No. -

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 162 92 263 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 111 50 316 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 Strategic developments 39 0 0 Protests 23 1 1 Methodology 3 Riots 14 4 5 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 10 7 22 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 359 154 607 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

CAMEROON: NORTH-WEST REGION Humanitarian Access Snapshot August 2021

CAMEROON: NORTH-WEST REGION Humanitarian access snapshot August 2021 Furu-Awa It became more challenging for humanitarian organisations in recent months to safely reach people in need in Cameroon’s North-West region. A rise in non-state armed groups (NSAGs) activities, ongoing military operations, increased criminality, the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and the rainy Ako season have all made humanitarian access more difficult. As a result, food insecurity has increased as humanitarian actors were not able to provide food assistance. Health facilities are running out of drugs and medical supplies and aid workers are at increased risk of crossfire, kidnapping and violent attacks. Misaje Nkambe Fungom Fonfuka IED explosion Mbingo Baptist Hospital Nwa Road with regular Main cities Benakuma Ndu traffic Other Roads Akwaya Road in poor Wum condition and Country boundary Nkum Fundong NSAGs presence Oku but no lockdown Region boundaries Njinikom Kumbo Road affected by Division boundaries Belo NSAG lockdowns Subdivision boundaries Njikwa Bafut Jakiri Noni Mbengwi Mankon Bambui Andek Babessi Nkwen Bambili Ndop Bamenda Balikumbat Widikum Bali Santa N Batibo 0 40 Km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 1 Creation date: August 2021 Sources: Acces Working Group, OCHA, WFP. Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/north-west-and-south-west-crisis CAMEROON: NORTH-WEST REGION Humanitarian access snapshot August 2021 • In August 2021, four out of the six roads out of Bamenda were affected by NSAG-imposed lockdowns, banning all vehicle • During the rainy season, the road from Bamenda to Bafut and traffic, including humanitarian operations. -

North West Region Minmap

MINMAP NORTH WEST REGION SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED REGIONAL No Designation of PO/DPO Number of contracts Amount of Contracts No. page 1 BAMENDA CITY COUNCIL 2 835 836 376 3 2 EXTERNAL SERVICES 23 1 090 482 000 4 TOTAL 25 1 926 318 376 Boyo Division 3 EXTERNAL SERVICES 4 95 926 000 6 4 BELO COUNCIL 6 253 778 000 6 5 FONFUKA COUNCIL 12 201 778 000 7 6 FUNDONG COUNCIL 13 193 778 000 8 7 NJINIKOM COUNCIL 6 233 778 000 9 TOTAL 41 979 038 000 Bui Division 8 EXTERNAL SERVICES 10 172 900 000 10 9 JAKIRI COUNCIL 8 190 728 000 11 10 KUMBO COUNCIL 4 198 278 000 12 11 MBIAME COUNCIL 6 146 778 000 12 12 NKOR NONI COUNCIL 9 226 808 000 13 13 NKUM COUNCIL 6 73 778 000 14 14 OKU COUNCIL 15 508 778 000 15 TOTAL 58 1 518 048 000 Donga Mantung Division 15 EXTERNAL SERVICES 3 41 535 000 16 16 AKO COUNCIL 11 282 578 000 16 17 MISAJE COUNCIL 8 226 778 000 17 18 NDU COUNCIL 7 196 778 000 18 19 NKAMBE COUNCIL 12 357 778 000 18 20 NWA COUNCIL 6 180 778 000 19 TOTAL 47 1 286 225 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 35 MINMAP NORTH WEST REGION SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED REGIONAL No Designation of PO/DPO Number of contracts Amount of Contracts No. page Menchum Division 21 EXTERNAL SERVICES 5 66 850 000 20 22 BENAKUMA COUNCIL 5 174 000 000 20 23 WUM COUNCIL 8 246 000 000 21 24 ZHOA COUNCIL 5 204 000 000 22 25 FURU AWA COUNCIL 2 119 000 000 22 TOTAL 25 809 850 000 Mezam Division 26 EXTERNAL SERVICES 4 99 000 000 23 27 BAFUT COUNCIL 7 186 778 000 23 28 BALI COUNCIL 8 207 278 000 24 29 BAMENDA -

Policy Alternatives for the Cameroon Conflicts with Views on Abolishing the Federation Christmas Atem Ebini Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Policy Alternatives for the Cameroon Conflicts with Views on Abolishing the Federation Christmas Atem Ebini Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Christmas A. Ebini has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Augusto Ferreros, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Mi Young Lee, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. James Mosko, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty The Office of the Provost Walden University 2019 Abstract Policy Alternatives for the Cameroon Conflicts with Views on Abolishing the Federation by Christmas A. Ebini MSW, 2005 Howard University, Washington, DC MMFT, 2001Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX MS, 1995 Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX MBA, 1995 Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX BBA, 1985, Harding University, Searcy, AK AA, 1984 Ohio Valley College, Parkersburg, WV Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration: Homeland Security and Administration Walden University September 2019 Abstract The violent conflicts in the Northwest and Southwest provinces of Cameroon (Southern Cameroons) have obtained national and international attention. -

CAMEROON Situation Report Last Updated: 5 Aug 2021

CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 5 Aug 2021 HIGHLIGHTS (24 Sep 2021) North-West and South West situation report (1-31 July 2021 ) Humanitarian access further decreased due to the ban of cirulation for all vehicles in the North-West, increased hostilities and risks of collateral damage for humanitarian actors. Unidentified gunmen burned down a school in Bali subdivision in the North-West (NW) region and shot a chief examiner to death in Kumba town in the South- West (SW) region. There was an increase in the number of attacks against health facilities and medical staff. Several attacks targeting humanitarian actors were registered, including temporary abduction, seizing of personal valuables and denial of access to beneficiaries. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2021) CONTACTS Carla Martinez 2.2M 1.6M $361.6M $105.1M Head of Office Affected people in Targeted for Required Received [email protected] NWSW assistance in NWSW e r d n A y r Ali Dawoud r o S 29% ead of Sub-Office, North-West and 712.8K 333.9K Progress South-West region IDPs within or Returnees (former [email protected] displaced from IDP) in NWSW NWSW FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/1 Ilham Moussa 030/summary Head of Bamenda Sub-Office, North- 67.5K West region Cameroonian [email protected] refugees in Nigeria Marie Bibiane Mouangue Public information Officer [email protected] https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/cameroon/ Page 1 of 11 Downloaded: 24 Sep 2021 CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 5 Aug 2021 VISUAL (2 Feb 2021) Map of IDP, from the North-West and South-West Regions of Cameroon Source: OCHA, IOM, CHOI, Partners The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

CMR NWSW Shelter Cluster Factsheet June2002

CAMEROOON North-West/South-West Regions June 2020 Shelter Cluster Factsheet Ako Furu-Awa Misaje Fungom Donga-Mantung NIGERIA Menchum Nkambe Bum Nwa Menchum-Valley Ndu Legend Wum Boyo Noni Fundong Number of HHs Reached North-West Nkum Shelter/NFI Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo Akwaya Njikwa Bui Mbven 0 Bafut Jakiri Mbengwi MezamTubah 1 - 114 Babessi Momo Ngie Bamenda 2ndBamenda 3rd 115 - 500 Widikum Bamenda 1st Ndop Bali BalikumbatNgo-Ketunjia 501 - 3,646 Batibo Santa Manyu Eyumodjock Wabane Mamfe Upper Bayang Alou Lebialem Fontem West Shutsi F. Plan International/UNHCR, 06/2020 Nguti NEEDS ANALYSIS Toko Kupe-Manenguba South-West Bangem The need for shelter and NFIs remain present within the affected Mundemba communities in the crisis in the North West and South West regions of Konye Tombel Isangele Dikome Balue Cameroon. Ndian Kumba 2nd Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Centre As informed by UNHCR protection monitoring program, several Kombo Abedimo Meme Kumba 1st Idabato Kumba 3rd persons among them women and children were displaced in several Bamusso Mbonge villages within Bui, Ngo ketunjia, Ndonga Mantung and Momo Muyuka Littoral divisions in the North West region as they flee violent clashes between Atlantic Ocean West-CoastBuea None State Armed Groups and the State Defense Forces. Fako Tiko Limbe 2nd Limbe 1st Food, shelter/NFI, medical care are among the most dire items ± Limbe 3rd highlighted by the displaced population. Several households have 0 25 50 Kilometers been rendered homeless as their houses and belongings have been destroyed The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Root Crops in Eastern Africa

ROOT CROPS IN EASTERN AFRICA U Proceedings of a workshop held in Kigali, Rwanda, ARCHIV 23-27 November i 50204 1980 IL The International Development Research Centre is a public corporation created by the Parliament of Canada in 1970 to support research designed to adapt science and technology to the needs of developing countries. The Centre's activity is con- centrated in five sectors: agriculture, food and nutrition sciences; health sciences; information sciences; social sciences; and com- munications. IDRC is financed solely by the Parliament of Canada; its policies, however, are set by an international Board of Governors. The Centre's headquarters are in Ottawa, Canada. Regional offices are located in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. © International Development Research Centre 1982 Postal Address: Box 8500, Ottawa, Canada K1G 3H9 Head Office: 60 Queen Street, Ottawa, Canada International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan NG International Development Research Centre, Ottawa CA IDRC-177e Root crops in Eastern Africa : proceedings of a workshop held in Kigali, Rwanda, 23-27 Nov. 1980. Ottawa, Ont., IDRC, 1982. 128 p. :ill. !Root crops!, !plant breeding!, /genetic improvement!, !agricultural research!, /East Africa! !plant protection!, !plant diseases!, !pests of plants!, !cassava,', /sweet potatoes!, !conference report!, /list of participants!. UDC: 633.4(67) ISBN: 0-88936-305-6 Microfiche edition available 5aOL IDRC-1 77e Root Crops in Eastern Africa Proceedings of a workshop held in Kigali, R wan da, 23-27 November 1980 Cosponsored by Gouvernement de la Republique rwandaise, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, and the International Development Research Centre. 2 2 D Résumé Cette brochure traite principalement des deux tubercules alimentaires les plus importants en Afrique orientale, soit le manioc et la patate douce. -

Sociolinguistical Metamorphosis of the Moghamo Speaking People of Cameroon Fokou Mukum Sandy Fomund

Sociolinguistical metamorphosis of the moghamo speaking people of cameroon Fokou Mukum Sandy Fomund To cite this version: Fokou Mukum Sandy Fomund. Sociolinguistical metamorphosis of the moghamo speaking people of cameroon. 2020. hal-03032640 HAL Id: hal-03032640 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03032640 Preprint submitted on 1 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Title : Sociolinguistical Metamorphosis Of The Moghamo Speaking People Of Cameroon Author: Fokou Mukum Sandy Fomundam ( Department of African languages and linguistics university of Yaounde I Cameroon.) Email : [email protected] ABSTRACT: As human altitudes evolve, so too do languages change as time passes especially African languages .African languages are instrumental media through which the African identity, cosmic vision and culture can be expressed and a reliable means through which meaningful development and transformation of the African continent can take place. This paper gives an inside perspective of the synchronic metamorphosis of the moghamo language spoken in the north West region of Cameroon , it's main challenge which is language attribution caused by the bilingual and multilingual nature of the Republic of Cameroon and Remedies to these challenges.