Manapouri.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Oceanography of the New Zealand Fiords

ISSN 0083-7903, 88 (Print) ISSN 2538-1016; 88 (Online) Physical Oceanography of the New Zealand Fiords by B. R. STANTON and G. L. PICKARD New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 88 1981 NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH Physical Oceanography of the New Zealand Fiords by B. R. STANTON and G. L. PICKARD New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 88 1981 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ ISSN 0083-7903 Received for publication: January 1980 © Crown Copyright 1981 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES 4 LIST OF TABLES 4 ABSTRACT 5 11''TRODUCTION 5 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS 6 Inlet depth profiles 6 Freshwater inflow 9 Tides... 13 Internalwaves... 13 OCEANOGRAPHIC OBSERVATIONS DURING THE FIORDS 77 SURVEY 17 Salinity in the shallow zone 18 Temperature in the shallow zone . 23 Salinity in the deep zone 24 Temperature in the deep zone 25 Temperature-Salinity relationships 27 Transverse temperature and salinity variations 27 Off shore oceanographic conditions 27 Density 27 Dissolved oxygen 28 Deep-water exchange 29 COMPARISON OF FIORDS 77 DATA WITH PREVIOUS WORK 31 Milford Sound... 31 Caswell and Nancy Sounds 32 Doubtful Sound 32 Dusky Sound and Wet Jacket Arm 33 DEEP-WATER RENEWAL IN THE NEW ZEALAND FIORDS 33 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 35 LITERATURE CITED 35 APPENDIX 1: MEAN FRESHWATER INFLOW AT MILFORD SOUND 36 APPENDIX 2: FRESHWATER INFLOW TO DoUBTFUI.fI'HOMPSON SOUNDS IN 1977 37 3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. -

FIORDLAND NATIONAL PARK 287 ( P311 ) © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely ©

© Lonely Planet Publications 287 Fiordland National Park Fiordland National Park, the largest slice of the Te Wahipounamu-Southwest New Zealand World Heritage Area, is one of New Zealand’s finest outdoor treasures. At 12,523 sq km, Fiordland is the country’s largest park, and one of the largest in the world. It stretches from Martins Bay in the north to Te Waewae Bay in the south, and is bordered by the Tasman Sea on one side and a series of deep lakes on the other. In between are rugged ranges with sharp granite peaks and narrow valleys, 14 of New Zealand’s most beautiful fiords, and the country’s best collection of waterfalls. The rugged terrain, rainforest-like bush and abundant water have kept progress and people out of much of the park. Fiordland’s fringes are easily visited, but most of the park is impenetrable to all but the hardiest trampers, making it a true wilderness in every sense. The most intimate way to experience Fiordland is on foot. There are more than 500km of tracks, and more than 60 huts scattered along them. The most famous track in New Zealand is the Milford Track. Often labelled the ‘finest walk in the world’, the Milford is almost a pilgrimage to many Kiwis. Right from the beginning the Milford has been a highly regulated and commercial venture, and this has deterred some trampers. However, despite the high costs and the abundance of buildings on the manicured track, it’s still a wonderfully scenic tramp. There are many other tracks in Fiordland. -

Primary Health Care in Rural Southland

"Putting The Bricks In place"; primary Health Care Services in Rural Southland Executive Summary To determine what the challenges are to rural primary health care, and nlake reconlmendations to enhance sustainable service provision. My objective is to qualify the future needs of Community Health Trusts. They must nleet the Ministry of Health directives regarding Primary Healthcare. These are as stated in the back to back contracts between PHOs and inclividual medical practices. I have compiled; from a representative group of rural patients, doctors and other professionals, facts, experiences, opinions and wish lists regarding primary medical services and its impact upon them, now and into the future. The information was collected by survey and interview and these are summarised within the report. During the completion of the report, I have attempted to illustrate the nature of historical delivery of primary healthcare in rural Southland. The present position and the barriers that are imposed on service provision and sustainability I have also highlighted some of the issues regarding expectations of medical service providers and their clients, re funding and manning levels The Goal; "A well educated (re health matters) and healthy population serviced by effective providers". As stated by the Chris Farrelly of the Manaia PHO we must ask ourselves "Am I really concerned by inequalities and injustice? We find that in order to achieve the PHO goals (passed down to the local level) we must have; Additional health practitioners Sustainable funding And sound strategies for future actions through a collaborative model. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PAGE 1 CONTACTS Mark Crawford Westridge 118 Aparima Road RD 1 Otautau 9653 Phone/ fax 032258755 e-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements In compiling the research for this project I would like to thank all the members of the conlmunity, health professionals and committee members who have generously given their time and shared their knowledge. -

Manapouri Tracks Brochure

Safety Adventure Kayak & Cruise Manapouri Tracks Plan carefully for your trip. Make sure Row boat hire for crossing the Waiau your group has a capable and experienced River to the Manapouri tracks. leader who knows bushcraft and survival Double and single sea kayaks for rental Fiordland National Park skills. on Lake Manapouri. Take adequate food and clothing on Guided kayak and cruise day and Lake Manapouri your trip and allow for weather changes overnight tours to Doubtful Sound. All and possible delays. safety and paddling equipment supplied. Adventure Kayak & Cruise, Let someone know where you are Waiau St., Manapouri. going and when you expect to return. Sign Ph (03) 249 6626, Fax (03) 249 6923 an intention form at the Fiordland National Web: www.fiordlandadventure.co.nz Park Visitor Centre and use the hut books. Take care with river crossings, espe- cially after rain. If in doubt, sit it out. Know the symptoms of exposure. React quickly by finding shelter and providing warmth. Keep to the tracks. If you become lost - stop, find shelter, stay calm and wait for searchers to find you. Don't leave the area unless you are absolutely sure where you are heading. Hut Tickets Everyone staying in Department of Conservation huts must pay hut fees. With the exception of the Moturau and Back Valley huts, all huts on these tracks are standard grade, requiring one back country hut ticket per person per night. The Moturau hut on the Kepler Track requires a For further information contact: booking during the summer season, or two Fiordland National Park Visitor Centre back country hut tickets per person per Department of Conservation night in the winter. -

FJ-Intro-Product-Boo

OUR TEAM YOUR GUIDE TO FUN Chris & Sue Co-owners Kia or a WELCOME TO FIORDLAND JET Assistant: Nala 100% Locally Owned & Operated Jerry & Kelli Co-owners At Fiordland Jet, it’s all about fun! Hop on board our unique range of experiences and journey into the heart of Fiordland National Park – a World Heritage area. Our tours operate on Lake Te Anau and the crystal-clear, trout filled waters of the Upper Waiau river, which features 3 Lord of the Rings film locations. Travel deeper into one of the world’s last untouched wildernesses to the isolated and stunning Lake Manapouri, surrounded by rugged mountains and ancient beech forest. Escape the crowds and immerse yourself into the laid-back Kiwi culture. Located on Te Anau’s lake front, Fiordland Jet is the ideal place to begin your Fiordland adventure. We have a phone charging station, WIFI, free parking and a passionate team standing by to welcome you and help plan your journey throughout Fiordland. As a local, family owned company and the only scenic jet boat operator on these waterways, we offer our customers an extremely personal and unique experience. We focus on being safe, sharing an unforgettable experience, and of course having FUN! Freephone 0800 2JETBOAT or 0800 253 826 • [email protected] • www.fjet.nz Our team (from left): Lex, Laura, Abby, Rebecca, Nathan & Sim PURE WILDERNESS Pure wilderness JOURNEY TO THE HEART OF FIORDLAND Jet boat down the Waiau River, across Lake Manapouri, to the ancient forest of the Fiordland National Park. Enjoy the thrill of jet boating down the majestic trout-filled Waiau River, to the serene Lake Manapouri. -

Southland Tourism Key Indicators

SOUTHLAND TOURISM KEY INDICATORS June 2019 SOUTHLAND TOURISM SNAPSHOT Year End June 2019 Guest nights up 1.5% to 1,201,109 Total spend up 3.3% to $673M Southland is continuing to experience stable growth phase in spend across both domestic and international markets, including good growth of the UK, German and US markets. There have also been modest gains in both international and domestic commercial accommodation figures, despite growth in Airbnb listings. SOUTHLAND REGION TE ANAU GORE TOURISM SPEND STATISTICS INVERCARGILL THE CATLINS Total Spend in NZD Figures for Year End June STEWART IS. MRTE’s (Monthly Regional Tourism Estimates) • International visitor spend up 6.1% to $264 million • Domestic visitor spend up 1.5% to $409 million • Total spend up 3.3% to $673 million ACCOMMODATION STATISTICS • Top 5 International Markets 1. Australia (up 7.9%) Guest Night Figures for Year End June 2. USA (up 10.2%) CAM (Commercial Accommodation Monitor) 3. Germany (up 11.0%) • International guest nights up 2.8% to 725,017 4. UK (up 9.0%) • Domestic guest nights up 0.8% to 476,091 5. China (down 7.8%) Markets • Total guest nights up 1.5% to 1,201,109 • Occupancy rate down from 46.3% to 45.6% • Daily capacity up 2.4% to 2,350 stay-units International 39% Domestic 61% Average Length of Stay Year End June 1.80 1.99 Days Days Southland National 2.2% 0.2% Tourism Spend Estimate Year End June $400m Guest Nights Year End June $350m Domestic 1,300,000 $300m USA 1,200,000 UK 1,100,000 $250m Rest of Oceania 1,000,000 Rest of Europe 900,000 Rest of Asia $200m -

Te Anau Area Community Response Plan 2019

Southland has NO Civil Defence sirens (fire brigade sirens are not used to warn of Civil Defence emergency) Please take note of natural warning signs as your first and best warning for any emergency. Te Anau Area Community Response Plan 2019 Find more information on how you can be prepared for an emergency www.cdsouthland.nz In the event of an emergency, communities may need to support themselves for up to 10 days before assistance arrives. Community Response Planning The more prepared a community is the more likely it is that the community will be able to look after themselves and others. This plan contains a short demographic description of information for the Te Anau area, including key hazards and risks, information about Community Emergency Hubs where the community can gather, and important contact information to help the community respond effectively. Members of the Te Anau and Manapouri Community Response Groups have developed the information contained in this plan and will be Emergency Management Southlands first points of community contact in an emergency. The Te Anau/Manapouri Response Group Procedure and Milford Sound Emergency Response Plan include details for specific response planning for the Te Anau and wider Fiordland areas. Demographic details • Te Anau and Manapouri are contained within the Southland District Council area. • Te Anau has a resident population of approx. 2,000 people. • Manapouri has a resident population of approx. 300 people • Te Anau Airport, Manapouri is located 15 km south of Te Anau and 5 km north of Manapouri, on State Highway 95 • The basin community has people from various service industries, tourism-related businesses, Department of Conservation, fishing, transport, food, catering, and farming. -

The Milford Road

Walks from the Milford Road Key Summit - 3 hours return The Key Summit track is an ideal introduction to the impressive scenery and natural features of Fiordland National Park. The track starts at The Divide carpark Protect plants and animals and shelter and follows the Routeburn Remove rubbish Track for about an hour. It then branches off on a 20 minute climb to Key Summit, Bury toilet waste where there is a self guided alpine nature walk. Keep streams and lakes clean Walkers will pass a range of native Take care with fires vegetation: beech forest, sub-alpine shrublands, and alpine tarns and bogs. Camp carefully Birdlife is prolific and tomtits, robins, wood pigeons and bellbirds are commonly seen. Keep to the track Key Summit provides panoramic views Consider others over the Humboldt and Darran Mountains. During the last ice age, which ended about Respect our cultural heritage 14,000 years ago, a huge glacier flowed Enjoy your visit down the Hollyford Valley and overtopped Key Summit by 500 metres, with ice Toitu te whenua branches splitting off into the Eglinton and ( Leave the land undisturbed ) Greenstone Valleys. Lake Marian - 3 hours return The Lake Marian Track is signposted from a car park area about 1 km down the Hollyford Road. The track crosses the Hollyford River/ Whakatapu Ka Tuku by swing-bridge then passes through silver beech forest to a spectacular series of waterfalls, reached after 10 minutes. The track then becomes steep and sometimes muddy during the 1.5 hour ascent through forest to Lake Marian. Lake Marian is in a hanging valley, formed by glacial action, and this setting is one of the most beautiful in Fiordland. -

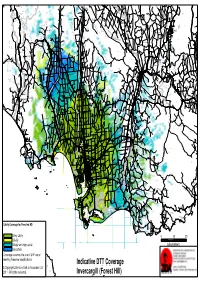

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

The New Zealand Gazette. 331

JAN. 20.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 331 MILITARY AREA No, 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No.· 12 (INVERCARGILL)-oontinued. 499820 Irwin, Robert William Hunter, mail-contractor, Riversdale, 532403 Kindley, Arthur William,·farm labourer, Winton. Southland. 617773 King, Duncan McEwan, farm hand, South Hillend Rural 598228 Irwin, Samuel David, farmer, Winton, Otapiri Rural Delivery, Winton. Delivery, Brown. 498833 King, Robert Park, farmer, Orepuki, Rural Delivery, 513577 Isaacs, Jack, school-teacher, The School, Te Anau. Riverton-Tuatapere. 497217 Jack, Alexander, labourer, James St., Balclutha. 571988 King, Ronald H. M., farmer, Orawia. 526047 Jackson, Albert Ernest;plumber, care of R. G. Speirs, Ltd., 532584 King, Thomas James, cutter, Rosebank, Balclutha. Dee St., Invercargill. 532337 King, Tom Robert, agricultural contractor, Drummond. 595869 James, Francis William, sheep,farmer, Otautau. 595529 Kingdon, Arthur Nehemiah, farmer, Waikaka Rural De. 549289 James, Frederick Helmar, farmer, Bainfield Rd., Waiki.wi livery, Gore. West Plains Rural Delivery, Inveroargill, 595611 Kirby, Owen Joseph, farmer, Cardigan, Wyndham. 496705 James, Norman Thompson, farmer, Otautau, Aparima 571353 Kirk, Patrick Henry, farmer, Tokanui, Southland. Rural Delivery, Southland. 482649 Kitto, Morris Edward, blacksmith, Roxburgh. 561654 Jamieson, Thomas Wilson, farmer, Waiwera South. 594698 Kitto, Raymond Gordon, school-teacher, 5 Anzac St., Gore. 581971 Jardine, Dickson Glendinning, sheep-farmer, Kawarau Falls 509719 Knewstubb, Stanley Tyler, orchardist, Coal Creek Flat, Station, Queenstown. Roxburgh. , 580294 Jeffrey, Thomas Noel, farmer, Wendonside Rural Delivery, 430969 Knight, David Eric Sinclair, tallow assistant, Selbourne St. Gore. Mataura. 582520 Jenkins, Colin Hendry, farm manager, Rural Delivery, 467306 Knight, John Havelock, farmer, Riverton, Rural Delivery, · Balclutha. Tuatapere. 580256 Jenkins, John Edward, storeman - timekeeper, Homer 466864 Knight, Ralph Condie, civil servant, 83 Ohara St., Inver. -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

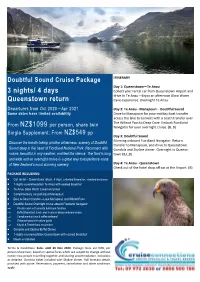

4 Days Queenstown Return

Doubtful Sound Cruise Package ITINERARY Day 1: Queenstown—Te Anau 3 nights/ 4 days Collect your rental car from Queenstown Airport and drive to Te Anau—Enjoy an afternoon Glow Worm Queenstown return Cave experience. Overnight Te Anau. Departures from Oct 2020—Apr 2021 Day 2: Te Anau - Manapouri - Doubtful Sound Some dates have limited availability Drive to Manapouri for your midday boat transfer across the lake to connect with a coach transfer over The Wilmot Pass to Deep Cove. Embark Fiordland From NZ$1099 per person, share twin Navigator for your overnight cruise. (B, D) Single Supplement: From NZ$549 pp Day 3: Doubtful Sound Discover the breath-taking, pristine wilderness scenery of Doubtful Morning onboard Fiordland Navigator. Return transfer to Manapouri, and drive to Queenstown. Sound deep in the heart of Fiordland National Park. Reconnect with Gondola and Skyline dinner. Overnight in Queens- nature, beautiful in any weather, and feel the silence. The fiord is long town (B,L,D) and wide and an overnight cruise is a great way to experience some of New Zealand’s most stunning scenery. Day 4: Te Anau - Queenstown Check out of the hotel drop off car at the Airport. (B) PACKAGE INCLUSIONS: • Car rental – Queenstown return, 4 days, unlimited kilometres, standard insurance • 1-nights accommodation Te Anau with cooked breakfast • Te Anau Glow Worm Caves excursion • Complimentary car parking at Manapouri. • Boat & Coach transfer—Lake Manapouri and Wilmot Pass • Doubtful Sound Overnight cruise aboard Fiordland Navigator: Private cabin with ensuite bathroom facilities Buffet Breakfast, lunch and 3 course dinner onboard cruise.