Performance Tuner Magazine Article TECH : Dyno Discrepancies Transcribed Because of Image Quality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prodrive USA MSRP Price Subaru (March 2008)UD

90 310-602-5445 LLC. Part Number Product Name Application Mar-08 Wheels Prodrive Cast Wheels MSRP EH/W5/007 P-WRC1 7X17" 5x100 ET52 - Anthracite All Subaru (not STI) $385.66 EH/W5/018 P-WRC1 7X17" 5x100 ET52 - Gold All Subaru (not STI) $385.66 P-WRC1-17-ET52S P-WRC1 7X17" 5x100 ET52 - Silver All Subaru (not STI) $385.66 EH/W5/016 P-WRC1 7.5X18" 5x100 ET53 - Gold All Subaru (not STI) $454.95 EH/W5/008 P-WRC1 7.5X18" 5x100 ET53 - Anthracite All Subaru (not STI) $454.95 P-WRC1-18-ET53S P-WRC1 7.5X18" 5x100 ET53 - Silver All Subaru (not STI) $454.95 P-WRC1-18-ET46CT P-WRC1 7.5X18" 5x100 ET46 5x100 - Crystal Titanium All Subaru $454.95 P-WRC1-18-ET46 P-WRC1 7.5X18" 5x100 ET46 5x100 - Rally Gold All Subaru $454.95 SL1787BY03A1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x100 - Anthracite All Subaru $424.61 SL1787BY03F1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x100 - Bright Flitter All Subaru $424.61 SL1787BY03O1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x100 - Gold All Subaru $424.61 SL1787BY03U1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x100 - Pewter All Subaru $424.61 SL1787BY06A1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x114.3 – Anthracite 2005 STI $424.61 SL1787BY06F1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x114.3 - Bright Flitter 2005 STI $424.61 SL1787BY06O1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x114.3 - Gold 2005 STI $424.61 SL1787BY06U1YS PFF7 8X18" ET51 5x114.3 – Pewter 2005 STI $424.61 430SB87548BBP-I GT1 7.5x18" 5x100 ET48 - Bright Flitter Forester $348.60 430SB87553BBP-I GT1 7.5x18" 5x100 ET53 - Bright Flitter WRX, Legacy $348.60 430NG87553BBP-I GT1 7.5x18" 5x100 ET53 - Gold WRX, Legacy $348.60 430NG88553SP-I GT1 8.5x18" 5x114 ET53 - Gold 2005-07 STI $409.46 430AA88553SP-I GT1 8.5x18" -

Lola Aston Martin DBR1-2

Lola Aston Martin DBR1-2 Lola Aston Martin DBR1-2 n. 009 24h Le Mans 2009 P. Kox - H. Primat - S. Hall Scale CA31a Release Date Oct 2015 Motor Pinion/Gear Front Rims/Tyres Rear Rims/Tyres Digital Chassis Cokpit Flat-6 20.5K 11/28 17.3x8 17.3x10 1:32 150mm 36mm 92mm 63mm 80,2gr 1159C1 1152C1 SLOT.IT DIGITAL Inline Sidewinder Inline Boxer Anglewinder 4WD System Setup Nd Magnet Race Magnet Suspension Lights Carrera D132 SLOT.IT DIGITAL Standard Motor mount [1] X X X Compatible X Not Compatible [1] box stock standard: offset 1 mm Lola Aston Martin DBR1-2 The Lola-Aston Martin B09/60, also known as the Aston Martin DBR1-2, is a Le Specifically, the aero package was redesigned in order to match technical Mans Prototype LMP1 sports car, designed and built by Lola Cars International, and marketing needs. The front of the car was redesigned to bear an jointly developed with Prodrive for Aston Martin Racing, conceived to enter the unmistakable Aston Martin grille shape. 24 Hours of Le Mans and the Le Mans Endurance Series Championship. The model was painted with the traditional ‘powder blue’ and orange The model was powered by the same atmospheric engine used on the Aston Gulf Oil pattern, due to the oil company sponsorship. Racing numbers Martin DBR9 GT1, that, thanks to the larger air restrictors allowed in the LMP1 007, 008, 009 are a clear reminder of what sort of cars is driven by category for production based blocks, reached 660 Hp. The motor itself was James Bond. -

180Kw Power Ranger!

#1610, 15 September 2016, page 12. 180KW POWER RANGER! WHEELS IMAGE #1610, 15 September 2016, page 12. Tickford is back! EXCLUSIVE: Iconic Ford performance badge set to make a comeback with Prodrive road car project A HOT Ford Ranger and hyped-up the old Ford Tickford Experience PRA Garage has also been from V8 racing at the end of 2015. Mustang will be the first two (FTE) high performance brand appointed an official wholesaler “People associate us with Ford models from a road car business was a joint-venture sanctioned by and retailer of the global Ford product and we have no plans to established by the Blue Oval’s the factory (see breakout), as was Performance Parts catalogue. work on anything else,” Nash said. former factory V8 Supercars team, its successor Ford Performance “PRA Garage is going to build Tuning work will cover off both Prodrive Racing Australia (PRA). Vehicles (FPV), PRA is going it performance and enhancement engine and chassis, as well as The venture has been alone without official backing of parts for ultimately most of the delivering exterior and interior registered as PRA Garage Ford Australia’s local sales and (Ford) products, but initially it’s styling enhancements. but is expected to be marketing arm. to do with Ranger and Mustang,” Development work is being marketed under the But there is some involvement PRA co-owner Rod Nash told done in-house and through Tickford name from Ford internationally, as Wheels in an exclusive interview. suppliers here and overseas. associated with parts and accessories are being Planning work began on Bosch Australia has been local fast Fords in developed by PRA Garage in the PRA Garage project two contracted to test modifications to the 1990s and conjunction with Ford Asia Pacific years ago as Nash and co faced an OEM level. -

Engine Test Facility to the Installation, Commissioning and Training on the Test Equipment, Froude Hofmann Can Provide a Total Solution

Total System Capability From the planning and specifying of the engine test facility to the installation, commissioning and training on the test equipment, Froude Hofmann can provide a total solution. PART OF THE FKI GROUP OF COMPANIES Our team of experienced multi-disciplined engineers form the core skill base on which our business is built. From mechanical and electrical design of dynamometers to the development of sophisticated software systems for control and data acquisition, we can meet your requirements. The combined resources from our operations in the UK, Germany and the USA integrate to meet the increasing demands Engine of the market. The solutions we provide to the global customer base aim to meet these requirements of: Test Systems ● Cost competitive ● On-time delivery ● Total customer support ● High quality reliable products ● Customer satisfaction Typical engine test installation Major Users Include • Ford • Lotus Engineering • Hyundai • Steyr Daimler Puch • Daedong • Wartsila • PSA • Bentley • Triumph • Ricardo • MTU • Weber • Jaguar • KIA • Delphi • Scania • Proton • Tianjin • Land Rover • MIRA • Lubrizol • Perkins • Harley Davidson • Mahle • Nissan • Shell • Toyota • MAN • Honeywell • JCB • BMW • IDIADA • Aston Martin • Prodrive Tickford • Cummins • VTT Quality Assurance ISO9001 Quality Assurance ISO14001 Quality Assurance ISO9001 Certificate No. Q10350 Certificate No. EMS45645 Certificate No. 08 100 1785 Ford Q1:2002 Member Further information from: Head Office: Froude Hofmann, Blackpole Road, Worcester WR3 8YB, England Te l: +44 (0)1905 856800 Fax:+44 (0)1905 856811 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.froudehofmann.com ETSE 0505 Froude Hofmann maintains a policy of continuous research and development and specifications are subject to alteration without notice. -

Mini Wrc Team

MINI WRC TEAM Media Information MINI WRC TEAM. Media Information MINI WRC TEAM Media Information Contents. The legend returns: MINI lines up in the FIA WRC in 2011. Page 3 Ian Robertson: “MINI is returning to its roots.” Page 5 Dr Wolfgang Armbrecht: “For us 2011 is a learning year.” Page 7 Prodrive – a strong partner for MINI's comeback to rallying. Page 9 MINI WRC driver Kris Meeke in profile. Page 11 MINI WRC driver Daniel “Dani” Sordo in profile. Page 13 Meticulous development work the key to success. Page 15 The MINI WRC: Technical specifications. Page 16 The benchmark in the 1960s: the MINI Cooper S. Page 18 Rauno Aaltonen: “Every child must first be nurtured.” Page 20 Historic victories: MINI in international motorsport. Page 21 Press Contact. Page 22 MINI WRC TEAM Media Information The legend returns: MINI lines up in the FIA WRC in 2011. Munich, 2nd February 2011. The countdown is on to the return of MINI on the international motorsport stage. This season, the new MINI WRC Team will compete at selected rounds in the FIA World Rally Championship (WRC). The aim is to gain valuable experience, in order to be perfectly prepared for the complete 2012 World Championship season. The MINI WRC has been developed by Prodrive, based on the MINI Countryman. It is equipped with a 1.6-litre turbo engine derived from the MINI production models, which was developed by BMW Motorsport for use in series run according to FIA Super2000 regulations, including the World Touring Car Championship. As well as its works involvement with the MINI WRC Team, Prodrive is supplying the customer car to private rally teams, who will also run the car in the S2000 class of the World Rally Championship. -

Aston Martin Vantage Gt4

ASTON MARTIN VANTAGE GT4 THE VANTAGE GT4 IS AN BORN ON THE ROAD, BUILT TO RACE UNCOMPROMISING RACING CAR, BUT ABOVE ALL ELSE, IT’S AN In June 2006 a near standard circuits in the world, as well as updates for 2009, including a collection. The Vantage GT4 V8 Vantage finished 24th in championship series. new 4.7 litre engine, to enhance provides the perfect base for a ASTON MARTIN overall out of 220 starters at the performance and reliability wide variety of motorsport uses the Nürburgring 24 Hour race – In 2008, the N24 was first, of the car. and is ideal for club racing a staggering achievement second and third in its class at among other categories. It is among a field of mostly the Nürburgring 24 Hours; was Each Vantage GT4 is hand- eligible to compete in series specialised race homologated second, third and fourth overall built by Aston Martin Racing, a including: the FIA GT4 entrants. in the Britcar 24 Hour race, partnership between Aston European Cup; VLN despite competing against cars Martin and world-leading Endurance Championship at The Nürburgring 24 Hour led to in higher classes; and won five motorsport specialist, Prodrive. the Nürburgring; Britcar the car being named the races in the FIA GT4 It is built to Aston Martin’s Endurance Series; Dutch Vantage N24. Over the next Championship. exacting standards and is Supercar Challenge; Australian two years a succession of cars available to private teams and Endurance Championship; were built by Aston Martin The new 2009 Vantage GT4 individuals to compete in British GT4 Championship; Racing for private teams and from Aston Martin Racing national and international race German GT4 Championship; individuals to compete at some builds on the success of the series; as a track day car; or American SCCA Championship; of the most arduous race N24, but with many new simply to savour and enjoy in a and Dutch GT4 Championship. -

Ford Sierra Cosworth RS500 1990 Championship Winner Chassis MTRS01

Ford Sierra Cosworth RS500 1990 Championship Winner Chassis MTRS01 The Trakstar team was formed in 1989 to contest the British Touring Car Championship by Robb Gravett and Mike Smith together with team manager Malcolm Swetnam, poached from the previous year’s BTCC winning Prodrive BMW M3 team for whom Smith drove. Gravett drove the Ford Sierra Cosworth RS500 to victory first time out in the opening round of the 1989 BTCC at Oulton Park, he then went on to score a total of 4 wins, 5 pole positions and 8 fastest laps for runners up spot in BTCC Class 1 and 4th overall in the 1989 Championship. They would have won the Class 1 Championship in their rookie year when Andy Rouse had all his points deducted for running illegally modified Garret turbos but the FIA overrode this penalty on appeal as the French language edition of the FIA Yellow Book stated that “repairs” were allowed unlike the English edition. For the 1990 season Trakstar focussed their efforts on one car, MTRS01, for lead driver Robb Gravett, with Mike Smith joining him at Brands Hatch and Stig Blomqvist at Donington for the long distance races. This car, which was a new shell specified by Trakstar and built up by Dave Cook of Yortech Fabrications with Mountune engines producing 550bhp and the running gear from the previous year’s car including all the trick bits; Eggenberger suspension, Getrag 5-speed box and the Ron Harrop designed spool, known in the UK as the “Australian differential”. The result was a record-breaking season for Gravett and Trakstar with 9 wins, 8 pole positions and 8 fastest laps to finish first in Class A and win the overall 1990 British Touring Car Championship, the only Sierra Cosworth RS500 to do so. -

Formula One 1 Formula One

Formula One 1 Formula One Formula One Category Single seater Country International [1] Inaugural season 1950 Drivers 22 Teams 11 Constructors 11 Engine suppliers Cosworth · Ferrari · Mercedes · Renault Tyre suppliers Pirelli Drivers' champion Sebastian Vettel (Red Bull Racing) Constructors' champion Red Bull Racing [2] Official website www.formula1.com Current season Formula One Current season • 2013 Formula One season Related articles • History of Formula One • Formula One racing • Formula One regulations • Formula One cars • Formula One tyres Lists • Drivers • (GP winners • Champions • Runners-up) • Constructors • (GP winners • Champions • Runners-up) • Seasons • Grands Prix • Circuits • Race Promoters' Trophy winners • Points scoring systems • Engines • Tyres • National colors Formula One 2 • Sponsorship liveries • Racing flags • Red-flagged GPs • Fatal accidents • Drivers who never qualified • Female drivers • TV broadcasters • Video games Records • Drivers • (Wins • Poles • Fastest laps) • Constructors • (Wins) • Engines • Tyres • Races Organisations • FIA • FIA World Motor Sport Council • Formula One Group • Formula One Constructors Association • Formula One Teams Association • Grand Prix Drivers' Association Formula One, also known as Formula 1 or F1 and referred to officially as the FIA Formula One World Championship, is the highest class of single-seater auto racing sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The "formula", designated in the name, refers to a set of rules with which all participants' cars must comply. The F1 season consists of a series of races, known as Grands Prix (from French, originally meaning great prizes), held throughout the world on purpose-built circuits and public roads. The results of each race are evaluated using a points system to determine two annual World Championships, one for the drivers and one for the constructors. -

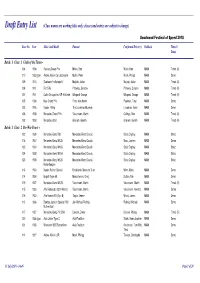

Entry List (Class Names Are Working Titles Only; Classes and Entries Are Subject to Change)

Draft Entry List (Class names are working titles only; classes and entries are subject to change) Goodwood Festival of Speed 2018 Race No. Year Make And Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) Paddock Timed / Demo Batch: 1 Class: 1 Clash of the Titans - 104 1906 Darracq Grand Prix Millen, Rod Millen, Rod MAIN Timed (A) 110 1923-type Avions Voisin C6 Laboratoire Mullin, Peter Moch, Philipp MAIN Demo 109 1916 Sunbeam 'Indianapolis' Majzub, Julian Majzub, Julian MAIN Timed (A) 108 1911 Fiat S76 Pittaway, Duncan Pittaway, Duncan MAIN Timed (A) 107 1911 Cottin-Desgouttes GP-Hillclimb Wingard, George Wingard, George MAIN Timed (A) 105 1908 Itala Grand Prix Frans Van Haren Paalman, Tony MAIN Demo 102 1903 Napier 100hp The Louwman Museum Louwman, Evert MAIN Demo 106 1908 Mercedes Grand Prix Viessmann, Martin Collings, Ben MAIN Timed (A) 103 1903 Mercedes 60hp Graham, Gareth Graham, Gareth MAIN Timed (A) Batch: 1 Class: 2 Pre-War Power - 122 1939 Mercedes-Benz T80 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static 118 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125 Mercedes-Benz Classic Mass, Jochen MAIN Demo 125 1939 Mercedes-Benz W165 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static 124 1938 Mercedes-Benz W154 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static 123 1938 Mercedes-Benz W125 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static Rekordwagen 113 1933 Napier-Railton Special Brooklands Museum Trust Winn, Allan MAIN Demo 114 1934 Bugatti Type 59 Manocherian, Greg Dutton, Tim MAIN Demo 119 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125 Viessmann, Martin Viessmann, Martin MAIN Timed (B) 115 1933 -

Vantage-GT4-Brochure-2014.Pdf

ASTON MARTIN VANTAGE GT4 The Aston Martin Vantage GT4 is the of Aston Martin Racing cars, while the most popular GT4 car in the world. interior has been stripped with a centrally More than 100 cars have been made and mounted bagged fuel tank which aids are competing in race series across the better weight distribution and comes with globe. twin quick fill entries in the rear quarter- lights. Like the Vantage GT3 and Vantage GTE, the car's foundation is the acclaimed This latest spec of car has a new Vantage road car and it carries over the aerodynamic package. An adjustable same chassis, V8 powertrain and drive carbon fibre rear wing works in train, including the semi automatic sports conjunction with a larger front splitter to shift system. The springs and dampers increase downforce for greater dynamic are upgraded to racing specification with performance. stiffened front and rear anti-roll bars and the option for rose-jointed wishbones. With nearly 300 kg shaved off the weight of the car and with more than 400 bhp Safety is paramount on the Vantage GT4. available the Vantage GT4 is the perfect The car has the same FIA-approved entry to GT racing. roll cage as found on the entire range “We have taken the opportunity to make some quite dramatic aerodynamic enhancements to the Vantage GT4, which will close the performance gap between this entry level GT car and the GT3." John Gaw, managing director ASTON MARTIN VANTAGE GT4 TECHNICAL SPECIFICation ENGINE & TRANSMISSION INTERIOR DATA SYSTEM Aston Martin Racing 4.7 litre V8 engine Recaro Pole -

Prodrive GRB ECU

Prodrive GRB ECU Introduction The Prodrive GRB ECU is designed as a direct replacement for the standard Denso ECU supplied in a Japanese homologated, 2.0 Litre Subaru WRX Sti (MY2008 onwards). The Prodrive GRB is supplied loaded with a base map that is suitable for starting the engine prior to tuning, which is required for maximum performance. The ECU supports the standard features on the car including variable valve timing of up to four camshafts and electronic (fly-by-wire) throttle control. Full support is also provided for wideband lambda sensing and the tumble valves (TGVs) between the plenum and cylinder head in each intake runner that are employed to reduce hydrocarbon emissions during starting. (Support is not provided for cruise control.) The ECU has been designed to integrate completely with the car electronic systems, which communicate via the vehicle CAN bus. The Prodrive GRB Differential Controller is also available for the car and this communicates via the same CAN bus, enabling differential control strategies to be integrated with the ECU. The GRB has an additional on board data logger with removable Compact flash card. This logger can store values from ECU parameters and data passed along the vehicle CAN bus from the Prodrive GRB Differential Controller. The GRB has reverse-battery, over-voltage and load dump protection built in as standard. Sensor supply and signal ground pins are also protected against shorts to battery positive and negative. Advanced software features include traction control, launch control, over-run boost, gearshift strategies and scrutineering modes for single make championships. Installation The Prodrive GRB ECU is a direct replacement for the standard ECU supplied by Subaru and as such must be installed using the standard loom also supplied by Subaru. -

Aston-Martin-Vantage-GT3-2013.Pdf

ASTON MARTIN VANTAGE GT3 & GT The Vantage GT3 and Vantage GT for A carbon fibre propshaft mates the Most dramatic of all are the the Grand Am series, have been engine to an Xtrac six-speed aerodynamics, which contribute to a designed from the ground up to offer sequential transmission with muscular and purposeful stance, customers the latest in race-car semi-automatic paddle shift gear while maintaining the beauty of the technology and embrace all the change. V12 Vantage. experience Aston Martin Racing has learnt from years of engineering and Like all Aston Martin racing cars, the The Vantage GT3 is eligible for competing in international sports car Vantage GT3 uses the Vantage road numerous race series around the racing with the DBR9, DBRS9 and car's bonded aluminium chassis to world, including the ADAC GT the latest Vantage GTE. create a light and stiff structure. This Masters, Nürburgring VLN, Blancpain combined with a shorter wheelbase Endurance Series, British GT, The Vantage GT3 has a modified and lower engine position contribute Japanese Super GT, Malaysian Super version of Aston Martin’s production to enhanced handling and Series, Asian Le Mans Series, 6.0 litre V12 engine and its position performance. Driveability is European Le Mans Series, Brazilian has been optimised further to enhanced further with the latest Endurance Belcar, Pirelli World improve weight balance. Thanks to race-developed ABS and traction Challenge and Open GT among this built-in level of performance and control systems, which are fitted as others. the performance balancing in this standard. As such, the gap between class, the Vantage GT3 does not pro and am drivers is substantially A Vantage Super GT has also been require expensive yearly upgrades to reduced.