SC00-1998 Barley Vs. S. FL Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SC12-1500 Jurisdictional Answer Brief

CASE NO.: SC12-1500 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA EMPIRE WORLD TOWERS, LLC, ET AL., Petitioners, v. CDR CRÉANCES, S.A.S., Respondent. On Review from the Third District Court of Appeals CASE NO.: 3D11-159 RESPONDENT’S JURISDICTIONAL BRIEF Scott B. Cosgrove KASOWITZ, BENSON, TORRES & FRIEDMAN LLP 1441 Brickell Avenue, Suite 1420 Miami, Florida 33131 Marcos Daniel Jiménez MCDERMOTT WILL & EMERY 333 S.E. 2nd Avenue, Suite 4500 Miami, Florida 33131-4336 Lauri Waldman Ross ROSS & GIRTEN 9130 S. Dadeland Blvd., Suite 612 Miami, Florida 33156 Attorneys for Respondent TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 II. STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS ................................................. 1 III. SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................................................... 6 IV. ARGUMENT ....................................................................................................6 A. The Legal Framework for Conflict Jurisdiction ............................................ 6 B. Empire World Towers Does Not Conflict with Dania Jai-Alai .................... 7 V. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................9 -i- TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) CASES Babe Elias Builders, Inc. v. Pernick, 765 So. 2d 119 (Fla. 3d DCA 2000) ..................................................................... 9 Dania Jai-Alai Palace, Inc .v. Sikes, 450 So. 2d 1115 (Fla. 1984) ........................................................................passim -

Lobbying in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbying In Miami-Dade County 2013 Annual Report HARVEY RUVIN, Clerk of Circuit & County Courts and Ex-Officio Clerk to the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners Prepared by: Christopher Agrippa, Director Clerk of the Board Division Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration SECTION I REGISTRATION BY LOBBYIST Printed on: 1/7/2014 Page 3 of 72 Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration A ALFORD, JONATHAN 2440 RESEARCH BLVD ROCKVILLE MD 20850 ABOODY, JASON 9965 FEDERAL DRIVE OTSUKA AMERICA PHARMACEUTICALS COLORADO SPRINGS CO 80921 THE SPECTRANETICS CORPORATION ALLY, DEANNA 700 10TH AVENUE SOUTH SUITE 20 MINNEAPOLIS MI 55415 ABRAMS, MICHAEL 801 BRICKELL AVENUE STE 900 ZYGA TECHNOLOGY, INC. MIAMI FL 33131 BALLARD PARTNERS ALSCHULER, JR, JOHN H 99 HUDSON ST 3 FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 ACOSTA, EDWARD 100 DENNIS DRIVE BECKHAM BRAND LIMITED READING PA 19606 SURGICAL SPECIALITIES CORPORATION ALVAREZ, JORGE A 95 MERRICK WAY 7TH FLOOR CORAL GABLES FL 33134 ACOSTA, PABLO 131 MADEIRA AVE PH COMMUNITY CONSULTANTS, INC. CORAL GABLES FL 33134 CLEVER DEVICES INC AMSTER, MATTHEW G COMTECH ENGINEERING 200 S BISCAYNE BLVD Ste 850 MIAMI FL 33131 FLORIDA DEVELOPMENT GROUP, INC METRO GAS FL LLC NETZACH YISROEL TORAH CENTER, INC MIAMI DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY SURGICAL PARK CENTER, LTD ADLER, BRIAN ANDARA, CHRISTOPHER D 1450 BRICKELL AVENUE SUITE 2300 11767 MEDICAL LLC MIAMI FL 33131 MIAMI FL 33156 19301 WEST DIXIE STORAGE, LLC ORBIS MEDICAL ANSALDOBREDA, INC ANDERSON, MELISSA P MIRON REALTY COMPANY 8555 NW 64TH STREET MODANI CAPITAL LLC DORAL FL 33166 PMG AVENTURA, LLC CROWN CASTLE USA SONNENKLAR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP THE ASSOC. -

Vendor List for Campaign Contributions

VENDOR LIST FOR CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS Vendor # Vendor Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Contact Name Phone Email 371 3000 GRATIGNY ASSOCIATES LLC 100 FRONT STREET SUITE 350 CONSHOHOCKEN PA J GARCIA [email protected] 651 A & A DRAINAGE & VAC SERVICES INC 5040 KING ARTHUR AVENUE DAVIE FL 954 680 0294 [email protected] 1622 A & B PIPE & SUPPLY INC 6500 N.W. 37 AVENUE MIAMI FL 305-691-5000 [email protected] 49151 A & J ROOFING CORP 4337 E 11 AVENUE HIALEAH FL MIGUEL GUERRERO 305.599.2782 [email protected] 1537 A NATIONAL SALUTE TO AMERICA'S HEROES LLC 10394 W SAMPLE ROAD SUITE 200 POMPANO BEACH FL MICKEY 305 673 7577 6617 [email protected] 50314 A NATIVE TREE SERVICE, INC. 15733 SW 117 AVENUE MIAMI FL CATHY EVENSEN [email protected] 7928 AAA AUTOMATED DOOR REPAIR INC 21211 NE 25 CT MIAMI FL 305-933-2627 [email protected] 10295 AAA FLAG AND BANNER MFG CO INC 681 NW 108TH ST MIAMI FL [email protected] 43804 ABC RESTAURANT SUPPLY & EQUIPM 1345 N MIAMI AVENUE MIAMI FL LEONARD SCHUPAK 305-325-1200 [email protected] 35204 ABC TRANSFER INC. 307 E. AZTEC AVENUE CLEWISTON FL 863-983-1611 X 112 [email protected] 478 ACADEMY BUS LLC 3595 NW 110 STREET MIAMI FL V RUIZ 305-688-7700 [email protected] 980 ACAI ASSOCIATES, INC. 2937 W. CYPRESS CREEK ROAD SUITE 200 FORT LAUDERDALE FL 954-484-4000 [email protected] 14534 ACCELA INC 2633 CAMINO RAMON SUITE 500 SAN RAMON CA 925-659-3275 [email protected] 49840 ACME BARRICADES LC 9800 NORMANDY BLVD JACKSONVILLE FL STEPHANIE RABBEN (904) 781-1950 X122 [email protected] 1321 ACORDIS INTERNATIONAL CORP 11650 INTERCHANGE CIRCLE MIRAMAR FL JAY SHUMHEY [email protected] 290 ACR, LLC 184 TOLLGATE BRANCH LONGWOOD FL 407-831-7447 [email protected] 53235 ACTECH COPORATION 14600 NW 112 AVENUE HIALEAH FL 16708 ACUSHNET COMPANY TITLEIST P.O. -

Carlos Lopez-Cantera, Statewide Chair 150 Alhambra Circle, Suite 925 Coral Gables, FL 33134 [email protected]

Carlos Lopez-Cantera, Statewide Chair 150 Alhambra Circle, Suite 925 Coral Gables, FL 33134 [email protected] Southern District Manny Kadre, Conference Chair 133 Sevilla Avenue Coral Gables, FL 33134 (305) 567-3582 Ext. 224 [email protected] Georgina A. Angones University of Miami School of Law 1203 Santona Street Coral Gables, FL 33146 (305)284-6470 [email protected] Ellyn Setnor Bogdanoff Becker & Poliakoff 1 East Broward Blvd. Suite 1800 Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33301 (954)987-7550 [email protected] Reginald J. Clyne Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer, P.A. 9300 South Dadeland Boulevard, 4th Floor Miami, FL 33156 (305)670-1101 [email protected] Kendall B. Coffey Coffey Burlington 2601 South Bayshore Drive Miami, FL 33133 (305)858-2900 [email protected] 1 Vivian de las Cuevas-Diaz Holland & Knight 701 Brickell Avenue Suite 3000 Miami, FL 33131 (305) 789-7452 [email protected] Renier Diaz de la Portilla 1481 NW 22nd Street Miami, FL 33142 (305) 325-1079 [email protected] Albert E. Dotson, Jr. Bilzin Sumberg Baena Price & Axelrod LLP 1450 Brickell Avenue, 23rd Floor Miami, FL 33131 (305) 350-2411 [email protected] Peter M. Feaman 3695 West Boynton Beach Blvd., Suite 9 Boynton Beach, FL 33436 (561) 734-5552 [email protected] Robert H. Fernandez, Esq. Partner Zumpano Castro 500 South Dixie Highway Suite 302 Coral Gables, FL 33146 (305) 503-2990 [email protected] 2 Daniel Foodman Waserstein Nunez & Foodman 1111 Brickell Ave Suite 2200 Miami, FL 33131 (305) 760-8503 [email protected] Philip Freidin Freidin, Dobrinsky, Brown & Rosenblum P.A. -

Witness Statement of Mr. Oscar I. Rivera Rivera

IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION UNDER THE ARBITRATION RULES OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SETTLEMENT OF INVESTMENT DISPUTES OMEGA ENGINEERING LLC AND MR. OSCAR RIVERA CLAIMANTS v. THE REPUBLIC OF PANAMA RESPONDENT WITNESS STATEMENT OF MR. OSCAR I. RIVERA RIVERA Counsel for Claimants JONES DAY JONES DAY 600 Brickell Avenue 21 Tudor Street Brickell World Plaza, Suite 3300 London EC4Y 0DJ Miami, Florida 33131 England United States JONES DAY INTERNATIONAL DISPUTE RESOURCES 51 Louisiana Avenue, N.W. 701 Brickell Avenue, Suite 1550 Washington, DC 20001 Miami, FL 33131 United States United States 25 JUNE 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 II. HISTORY OF OMEGA ENGINEERING LLC ........................................................................ 4 III. THE DECISION TO ENTER PANAMA’S BOOMING CONSTRUCTION MARKET ................... 7 A. Background .......................................................................................................... 7 B. First Steps in Panama: PR Solutions S.A. and Omega Engineering Inc. .............................................................................................................................. 10 1. PR Solutions: Protecting the Valuable Omega U.S. Brand While Entering a New Market ............................................................................ 12 2. Omega Engineering Inc. .......................................................................... 13 C. The -

Abrams, Michael I

Abrams, Michael I. Address One SE Third Avenue 25th Floor Organization Akerman Senterfitt City Miami Telephone (305) 982-5676 Fax State FL Zip 33131 Email [email protected] Principal Name Issue Description Date Amount Payment Comments Annual Fee 10/1/2009 $500.00 2009 Registration Akerman Senterfitt Federal and local lobbying for the City of 1/7/2005 $100.00 Miami issues Camillus House Funding 2/1/2005 $100.00 Hunt/Moss J.V. Marlins Stadium Parking Lot 10/1/2009 $100.00 Miami Art Museum Funding 1/17/2006 $100.00 Miami Museum of Science & Planetarium Funding 2/1/2005 $100.00 Ultra Music Festival Ultra Music Festival 10/1/2009 $100.00 Lobbyists Registered between 12/12/2008 and 12/9/2009 Page 1 of 190 Printed on 12/9/2009 8:01:13 AM Acosta, Pablo Address 131 Madeira Ave., PH Organization Pablo Acosta, P.A. City Coral Gables Telephone (305) 444-6169 Fax State FL Zip 33134 Email [email protected] Principal Name Issue Description Date Amount Payment Comments Annual Fee 2/13/2009 $500.00 2009 Registration Basketball Properties, LTD General Representation - 99% Miami Heat 7/3/2008 $100.00 Limited Partnership Bureau Veritas North America, Inc. General Representation 2/12/2009 $100.00 Florida Power & Light Services General Represenation 3/25/2009 $100.00 Van Wagner Communications, LLC Amendment to sign code 2/11/2008 $100.00 Lobbyists Registered between 12/12/2008 and 12/9/2009 Page 2 of 190 Printed on 12/9/2009 8:01:15 AM Adler, Brian S. -

Vendor List for Campaign Contributions

VENDOR LIST FOR CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS Vendor # Vendor Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Contact Name Phone Email 43343 11TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OF FL ATTN:SONYA BELLINGER, BUSINESS 1320 N.W. 14TH STREET MIAMI FL [email protected] 371 3000 GRATIGNY ASSOCIATES LLC 100 FRONT STREET SUITE 350 CONSHOHOCKEN PA J GARCIA [email protected] 651 A & A DRAINAGE & VAC SERVICES INC 5040 KING ARTHUR AVENUE DAVIE FL 954 680 0294 [email protected] 1622 A & B PIPE & SUPPLY INC 6500 N.W. 37 AVENUE MIAMI FL 305-691-5000 [email protected] 49151 A & J ROOFING CORP 4337 E 11 AVENUE HIALEAH FL MIGUEL GUERRERO 305.599.2782 [email protected] 881 A JOY WALLACE CATERING PRODUCTION INC 8501 SW 128 TERRACE MIAMI FL PRISCILLA 305-252-0020 [email protected] 45432 A QUICK BOARD-UP SERVICE, INC. 10501 NW 50 STREET STE 101 SUNRISE FL DAN KALELY 954-764-4282 [email protected] 7928 AAA AUTOMATED DOOR REPAIR INC 21211 NE 25 CT MIAMI FL 305-933-2627 [email protected] 608 AARDVARK 1935 PUDDINGSTONE DRIVE LA VERNE CA TURNER 909 451 6100 [email protected] 48891 AARON CONSTRUCTION GROUP, INC. 10820 NW 138 STREET BAY C-1 HIALEAH GARDENS FL LINA 7863626120 [email protected] 35204 ABC TRANSFER INC. 307 E. AZTEC AVENUE CLEWISTON FL 863-983-1611 X 112 [email protected] 478 ACADEMY BUS LLC 3595 NW 110 STREET MIAMI FL V RUIZ 305-688-7700 [email protected] 765 ACCURATE CONSTRUCTION SURVEY LLC 2841 DAY AVENUE MIAMI FL 305-447-6906 [email protected] 49840 ACME BARRICADES LC 9800 NORMANDY BLVD JACKSONVILLE FL LANDY HOLLOWAY [email protected] 290 ACR LLC 184 TOLLGATE BRANCH LONGWOOD FL 407-831-7447 [email protected] 46766 ACT PRODUCTIONS 407 LINCOLN ROAD SUITE #302 MIAMI BEACH FL JESUS ARANGO [email protected] 53235 ACTECH COPORATION 14600 NW 112 AVENUE HIALEAH FL 16708 ACUSHNET COMPANY TITLEIST P.O. -

Brickell Flatiron Neighborhood Guide Red

BRICKELL NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE A N I N S I D E R S G U I D E TO THE BEST OF BRICKELL, DOWNTOWN MIAMI'S MOST VIBRANT NEIGHBORHOOD T.305-400-7400 www.brickellflatiron.com 1001 SOUTH MIAMI AVENUE, MIAMI, FLORIDA 33130 Content 01-07 Dining & Cocktails 08-10 Services 11-12 Retail 13-15 Health & Beauty 16-17 Parks & Culture 18-19 Hotels 2 0 - 2 1 Neighborhood Map BRICKELL FLATIRON NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE DINING & COCKTAILS D I N I N G & C O C K TA I L S TOASTED TAMARINA With fresh bagels made right in front of you, Toasted delivers A restaurant specializing in coastal Italian cuisine, an excellent breakfast every day of the week. featuring a Crudo Bar & an al fresco Champagne Bar. 83 SW 8TH STREET, 600 BRICKELL AVENUE, MIAMI, FL 33130 MIAMI, FL 33131 (305) 400-6996 (305) 770-6223 C O Y A MARION Enjoy true Peruvian food with a contemporary twist while Marion offers traditional Mediterranean fare and products sipping on pisco cocktails or a selection from Coya's of the highest quality paired with superb service. comprehensive rum & tequila bar. 1111 SW 1ST AVENUE, 999 BRICKELL AVENUE, MIAMI, FL 33130 MIAMI, FL 33131 (786) 717-7512 (305) 415-9990 1 D I N I N G & C O C K TA I L S A R E A 3 1 E L T U C A N Area 31 in the buzzing Epic Hotel + Residences has a El Tucan is a modern-day "dinner and a show" cabaret nice Brickell view, plus they’ve just revamped their whole featuring luxe libations as well as Caribbean and South outdoor dining space. -

Lobbying in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbying In Miami-Dade County 2015 Second Quarter Report 04/01/2015 Through 06/30/2015 HARVEY RUVIN, Clerk Circuit & County Courts and Ex-Officio Clerk to the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners Prepared by: Christopher Agrippa, Director Clerk of the Board Division Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration SECTION I REGISTRATION BY LOBBYIST Printed on: 9/30/2019 Page 2 of 25 Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration A FORSE PRESIDENTIAL LLC HM SIX, LLC ACOSTA, PABLO NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING COMPANY, LLC 131 MADEIRA AVENUE PENTHOUSE NIGHTLIFE BREWING COMPANY, LLC CORAL GABLES FL 33134 SOUTHEAST INVESTMENTS, INC. ALLIED CONTRACTORS, INC THE GRAND CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION, INC MDM RETAIL, INC WRC PROPERTIES INC YGRENE ENERGY FUND FLORIDA LLC. ARZA, HUGO P ADLER, BRIAN 701 BRICKELL AVENUE #3000 1450 BRICKELL AVENUE SUITE 2300 MIAMI FL 33131 MIAMI FL 33131 BROWN DEVELOPMENT GROUP, LLC GARY COHEN FORSE PRESIDENTIAL LLC MAYRES, LLC NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING COMPANY, LLC MNK HOSPITALITY LLC AND MNK INVESTMENTS, LLC NIGHTLIFE BREWING COMPANY, LLC SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, LP AND SDG DADELAND ASSN. SOUTHEAST INVESTMENTS, INC. THE GRAND CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION, INC ALFARO-MARTINEZ, LUIS WRC PROPERTIES INC 270 AVENUE MUNIZ RIVER HATOREY PR 00918-1901 ASPER, THAIS A BARCLAYS CAPITAL 801 ARTHUR GODFREY RD STE #401 MIAMI BEACH FL 33140 ALSUP, II, THOMAS C ACCENTURE LLP 10 BURTON HILLS BOULEVARD NEW FLYER OF AMERICA, INC NASVILLE TN 37215 TURNBERRY ASSOCIATES / SOFFER FAMILY CCA OF TENNESSEE, LLC ATKINSON, ALAN S ALVAREZ RETUERTO, ANA I 100 S. POINTE DRIVE 777 SCUDDERS MILL ROAD MIAMI BEACH FL 33139 PLAINSBORO TOWNSHIP NJ 08536 DELL TECHNOLOGIES, INC. -

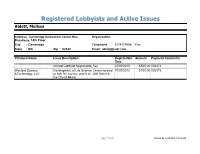

Active Registration and Issues

Registered Lobbyists and Active Issues Ablett, Melissa Address: Cambridge Innovation Center One Organization Broadway, 14th Floor City : Cambridge Telephone 6174179598 Fax: State : MA Zip : 02142 Email: [email protected] Principal Name Issue Description Registration Amount Payment Comments Date Annual Lobbyist Registration Fee 07/07/2015 $525.00 005373 Wexford Science Development of Life Science Center located 07/07/2015 $105.00 005373 &Technology, LLC at NW 7th Avenue and N.W. 20th Street in the City of Miami. Page 1 of 323 Printed On 12/30/2015 8:31:48 AM Registered Lobbyists and Active Issues Abreu, Sergio Address: 5101 N.W. 21st Avenue, Suite 460 Organization City : Ft. Lauderdale Telephone 3059702288 Fax: State : FL Zip : 33309 Email: Principal Name Issue Description Registration Amount Payment Comments Date Annual Lobbyist Registration Fee 03/24/2015 $0.00 Principal - Fee Exempt TECO Energy Noise waiver or permitting issues. 03/24/2015 $0.00 Principal - Fee Exempt Page 2 of 323 Printed On 12/30/2015 8:31:48 AM Registered Lobbyists and Active Issues Acosta, Pablo Address: 131 Madeira Ave., PH Organization Pablo Acosta, P.A. City : Coral Gables Telephone 3054446102 Fax: State : FL Zip : 33134 Email: [email protected] Principal Name Issue Description Registration Amount Payment Comments Date Annual Lobbyist Registration Fee 05/06/2015 $525.00 1272 Basketball Properties, LTD General Representation - 99% Miami Heat 07/03/2008 $100.00 1484 Limited Partnership Bureau Veritas North General Representation 02/12/2009 $100.00 1452 America, Inc. Florida Power & Light General Represenation 03/25/2009 $100.00 1582 Services MDM Retail LTD City/CRA Incentives 05/18/2015 $105.00 249103 Miami Big Block, LLC Miami Innovation Tower 05/06/2015 $105.00 1274 Van Wagner Amendment to sign code 02/11/2008 $100.00 1418 Communications, LLC Page 3 of 323 Printed On 12/30/2015 8:31:48 AM Registered Lobbyists and Active Issues Adams, Alexander W. -

Winston & Strawn's Cover Sheet Application for Allowance And

5"1-.9 - ,,l 1 Donald K. Dankner (No. 0186536) Thomas Blakemore (No. 03121566) 2 DavidAgay (No. 06244314) STRAWN 3 WINSTON & 35 West Wacker, Suite 4200 4 Chicago, IL 60601 312-558-5600 (Phone) 5 312-558-5700 (Facsimile) Counsel to Debtors and Debtors in Possession 6 7 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 11 Case No. 01-30923 DM 12 In re Chapter 11 Case 13 PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC a California corporation, COMPANY, [No Hearing Scheduled] 14 Debtor. 15 Federal I.D. No. 94-0742640 16 17 WINSTON & STRAWN'S COVER SHEET APPLICATION FOR ALLOWANCE AND PAYMENT OF INTERIM COMPENSATION 18 AND REIMBURSEMENT OF EXPENSES FOR THE PERIOD OCTOBER 1, 2001 THRU OCTOBER 31, 2001 19 "Firm") submits its Cover Sheet Application (the "Application") 20 Winston & Strawn (the 21 for Allowance and Payment of Interim Compensation and Reimbursement of Expenses for the 22 Period of October 1, 2001- October 31, 2001 (the "Application Period"). In support of the 23 Application, the Firm respectfully represents as follows: 24 1. Pursuant to the Amendment to the Amended Application for Authority to 25 Employ and to continue the Employment of Special Counsel dated as of September 13, 2001, the 26 Firm is Counsel to the debtor and debtor-in-possession (the "Debtor"), employed under section 27 seq. Pursuant to the Order Establishing 28 327(e) of the Bankruptcy Code, 11 U.S.C. § 101 et. 4f001 t (L+ee d'1.lrI.M1'A1 1 1 Interim Fee Application and Expense Reimbursement Procedure entered on July 26, 2001 (the 2 "Fee Order"), the Firm hereby applies to the Court for allowance and payment of interim 3 compensation for services rendered and reimbursement of expenses incurred during the 4 Application Period. -

Lobbying in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbying In Miami-Dade County 2003 Annual Report HARVEY RUVIN, Clerk of Circuit & County Courts and Ex-Officio Clerk to the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners Prepared by Kay Sullivan, Director Clerk of the Board Division Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration SECTION I REGISTRATION BY LOBBYIST Printed on: Page 2 of 74 10/10/2007 Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration A ALVAREZ, MARK 625 NE 50 TERR 214 ABRAMS, DAVID S MIAMI FL 33137 150 EAST PALMETTO PARK ROAD SUITE 330 COSTA VERDE HOMEOWNERS ASSN BOCA RATON FL 33432 MORGAN STANLEY AND COMPANY ALVAREZ, RAMON 1750 PONCE DE LEON BLVD ABRAMS, MICHAEL MIAMI FL 33134 1 SW 3 AVE 28TH FLR DAVID PLUMMER & ASSOCIATES MIAMI FL 33131 ASSET MANAGEMENT OUT SOURCING AMADOR, ABEL BROWARD ADJUSTMENT SERVICES PO BOX 652107 MIAMI FL 33265 CIGNA HEALTHCARE ABEL HOMES LLC ACOSTA, PABLO 131 MADEIRA AVE PH ARGUDIN, ALBERTO CORAL GABLES FL 33134 P.O. BOX 650095 MIAMI FL 33265 COMCAST CORPORATION EFC HOLDINGS SANCHEZ, ZEINALI & ASSOCIATES MGE ARCHITECTS ARTECONA, MARIO 150 W FLAGLER ST 1820 ADLER, BRIAN MIAMI FL 33130 200 S. BISCAYNE BLVD #2500 MIAMI FL 33131 MIAMI BUSINESS FORUM ANELI INVESTMENTS LLC ARZA, HUGO ANGELO AND SUAN LAVECCHIA 2665 S BAYSHORE DR 200 EDUARDO GARCIA MIAMI FL 33133 FSE HOLDINGS, LTD ARZA CONSULTING & MANAGEMENT G.F.B. ENTERPRISES MANAGEMENT LLC KARLTON 54TH STREET ASSOCIATES AUTRY, THOMAS P LEN, LLC 18601 NW 2 AVE SHOMA DEVELOPMENT CORP. MIAMI FL 33169 SHOMA VI, INC COMCAST CABLE COMMUNICATIONS TURNPIKE COMMERCE PARK LLC B ALBERT, RONALD 2 S.