Contemporary Medieval Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Alphabetical list of Authors Clonmel Library Douglas Adams Kazuo Ishiguro Clonmel Library Issac Asimov PD James Ray Bradbury Robert Jordan Terry Brooks Kate Jacoby RecommendedRecommended Trudi Canavan Ursala K. Le Guin Arthur C Clarke George Orwell Susanna Clarke Anne McCaffery ReadingReading Philip K. Dick George RR Martin David Eddings Mervyn Peake Raymond E. Feist Terry Pratchett American Gods Philip Pullman Neil Gaiman Brandon Sanderson David Gemmell JRR Tolkein Terry Goodkind Jules Verne Robert A. HeinLein Kurt Vonnegut FantasyFantasy && Frank Herbert T.H. White Robin Hobb Aldous Huxley Clonmel Library ScienceScience FictionFiction Opening Hours & Contact Details Monday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Tuesday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Wednesday: 9.30 am – 8.00 pm Thursday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Friday: 9.30 am – 1pm & 2pm - 5pm Saturday: 10.00 am – 1pm & 2pm-5pm Phone: (052) 6124545 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.tipperarylibraries.ie/clonmel 11 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea AnAn IntroductionIntroduction Jules Verne First published 1869 toto FantasyFantasy French naturalist Dr. Aronnax embarks on an expedition to hunt down a sea monster, only to discover instead the && ScienceScience FictionFiction Nautilus, a remarkable submarine built by the enigmatic Captain Nemo. Together Nemo and Aronnax explore the antasy is a genre that uses magic and other supernatural forms underwater marvels, undergo a transcendent experience as a primary element of plot, theme, and/or setting. Fantasy is amongst the ruins of Atlantis, and plant a -

A Study of the Genre of T. H. White's Arthurian Books a Thesis

A Study of the Genre of T. H. White's Arthurian Books A Thesis for the Degree of Ph. D from the University of Wales Susan Elizabeth Chapman June 1988 Summary T. H. White's Arthurian books have been consistently popular with the general public, but have received limited critical attention. It is possible that such critical neglect is caused by the books' failure to conform to the generic norms of the mainstream novel, the dominant form of prose fiction in the twentieth century. This thesis explores the way in which various genres combine in The. Once alai Future King.. Genre theory, as developed by Northrop Frye and Alastair Fowler, is the basis of the study. Neither theory is applied fully, but Frye's and Fowler's ideas about the function of genre as an interpretive tool underpin the study. The genre study proper begins with an examination of the generic repertoire of the mainstream novel. A study of The. Qnce gknj Future King in relation to this form reveals that it exhibits some of its features, notably characterization and narrative, but that it conspicuously lacks the kind of setting typical of the mainstream novel. A similar approach is followed with other subgenres of prose fiction: the historical novel; romance; fantasy; utopia. In each case Thy Once angj Future King is found to exhibit some key features, unique to that form, although without sufficient of its characteristics to be described fully in those terms. The function of the comic and tragic modes within The. Qnce änd Future King is also considered. -

THE MANY FACES of MERLIN in MODERN FICTION Author(S): Christopher Dean Source: Arthurian Interpretations, Vol

THE MANY FACES OF MERLIN IN MODERN FICTION Author(s): Christopher Dean Source: Arthurian Interpretations, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Fall 1988), pp. 61-78 Published by: Scriptorium Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27868651 . Accessed: 09/06/2014 19:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Scriptorium Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Arthurian Interpretations. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.212.18.200 on Mon, 9 Jun 2014 19:11:41 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MANY FACES OF MERLIN IN MODERN FICTION1 Merlin, Arthur's enchanter and prophet, a figure ofmystery, ofmagic, and of awesome power, is a name that has been part of our literature formore than eight centuries. But the same creature is never conjured, for, as Jane Yolen says, was he not "a shape-shifter, a man of shadows, a son of an incubus, a creature of the mists" (xii)? Or, to quote Nikolai Tolstoy, as a "trickster, illusionist, philosopher and sorcerer, he represents an archetype to which the race turns for guidance and protection" (20). -

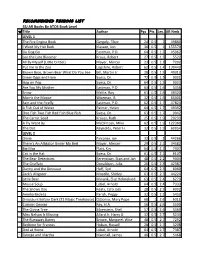

RECOMMENDED READING LIST SSJ AR Books by ATOS Book Level ✔️Title Author Pgs Pts Lev

RECOMMENDED READING LIST SSJ AR Books By ATOS Book Level ✔️Title Author Pgs Pts Lev. AR Nmb LEVEL 1 The Fire Engine Book Gergely, Tibor 24 0.5 1 49860 I Want My Hat Back Klassen, Jon 36 0.5 1 155570 Go Dog Go Eastman, P.D. 64 0.5 1.2 45962 Leo the Late Bloomer Kraus, Robert 27 0.5 1.2 5522 All By Myself (Little Critter) Mayer, Mercer 23 0.5 1.3 7202 Put me in the Zoo Lopshire, Robert 62 0.5 1.4 130449 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See Bill, Martin Jr. 28 0.5 1.5 40313 Green Eggs and Ham Suess, Dr. 72 0.5 1.5 9021 Hop on Pop Suess, Dr. 64 0.5 1.5 9023 Are You My Mother Eastman, P.D. 63 0.5 1.6 5456 Snow McKie, Roy 61 0.5 1.6 49420 Morris the Moose Wiseman, B. 32 0.5 1.6 65001 Sam and the Firefly Eastman, P.D. 62 0.5 1.7 47824 A Fish Out of Water Palmer, Helen 64 0.5 1.7 49392 One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish Suess, Dr. 63 0.5 1.7 9042 The Carrot Seed Krauss, Ruth 25 0.5 1.9 29233 A Fly Went By McClintock, Mike 62 0.5 1.9 122360 The Dot Reynolds, Peter H. 32 0.5 1.9 69954 LEVEL 2 Olivia Falconer, ian 32 0.5 2 44266 There's An Alligator Under My Bed Mayer, Mercer 29 0.5 2.1 34582 Big Max Platt, Kin 64 0.5 2.1 7307 Cat in the Hat Suess, Dr. -

The Once and Future King the Once and Future King

Prestwick House AP Literature SampleTeaching Unit™ Prestwick House Prestwick House * * AP Literature AP Literature Teaching Unit Teaching Unit * AP is a registered trademark of The College Board, * AP is a registered trademark of The College Board, which neither sponsors or endorses this product. which neither sponsors or endorses this product. AT.H. White’s P AT.H. White’s P The Once and Future King The Once and Future King Click here A P RESTWICK H OUSE P UBLIC A TION A P RESTWICK H OUSE P UBLIC A TION Item No. 309061 to learn more about this Teaching Unit! Click here to find more Classroom Resources for this title! More from Prestwick House Literature Grammar and Writing Vocabulary Reading Literary Touchstone Classics College and Career Readiness: Writing Vocabulary Power Plus Reading Informational Texts Literature Teaching Units Grammar for Writing Vocabulary from Latin and Greek Roots Reading Literature Advanced Placement in English Literature and Composition Individual Learning Packet Teaching Unit The Once and Future King by T. H. White written by Jill Clare Item No. 309061 The Once and Future King ADVANCED PLACEMENT LITERATURE TEACHING UNIT The Once and Future King Objectives By the end of this Unit, the student will be able to: 1. explain the elements of tragedy and explain how the text can be regarded as a tragedy. 2. analyze the text for evidence of foreshadowing and explain how foreshadowing contributes to the tone of the work. 3. analyze the text for thematic development and explain how specific themes contribute to the overall meaning of the text. -

Adaptation and Translation Between French and English Arthurian Romance" (Under the Direction of Edward Donald Kennedy)

Varieties in Translation: Adaptation and Translation between French and English Arthurian Romance Euan Drew Griffiths A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Edward Donald Kennedy Madeline Levine E. Jane Burns Joseph Wittig Patrick O'Neill © 2013 Euan Drew Griffiths ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract EUAN DREW GRIFFITHS: "Varieties in Translation: Adaptation and Translation between French and English Arthurian Romance" (Under the direction of Edward Donald Kennedy) The dissertation is a study of the fascinating and variable approaches to translation and adaptation during the Middle Ages. I analyze four anonymous Middle English texts and two tales from Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur that are translations and adaptations of Old French Arthurian romances. Through the comparison of the French and English romances, I demonstrate how English translators employed a variety of techniques including what we might define as close translation and loose adaptation. Malory, in particular, epitomizes the medieval translator. The two tales that receive attention in this project illustrate his use of translation and adaptation. Furthermore, the study is breaking new ground in the field of medieval studies since the work draws on translation theory in conjunction with textual analysis. Translation theory has forged a re-evaluation of translation as a literary medium. Using this growing field of research and scholarship, we can enhance our understanding of translation as it existed during the Middle Ages. -

Urban Fantasy Secret Societies and Shady Characters Fairy Tales And

Urban Fantasy Magical Realism —Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo —The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende —Storm Front by Jim Butcher —Summerlong by Peter S. Beagle —Highfire by Eoin Colfer —Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges —The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin —The Book of Hidden Things by Francesco Dimitri —Darkfever by Karen Marie Moning —A Green and Ancient Light by Frederic S. Durbin —Witchmark by C.L. Polk —Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel —One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Secret Societies and Márquez Shady Characters —Exit West by Mohsin Hamid —The Shape of Water by Guillermo del Toro —The Invisible Library by Genevieve Cogman —The Binding by Bridget Collins —Lent by Jo Walton —The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune Graphic Novels —The Lies of Locke Lamora by Scott Lynch —American Gods by Neil Gaiman —The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern —Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman —The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern —Monstress by Marjorie Liu —A Darker Shade of Magic by V.E. Schwab —The Complete ElfQuest by Wendy Pini Fairy Tales and —Nimona by Noelle Stevenson Mythology —Rat Queens by Kurtis J. Wiebe —The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Short Stories Arden —The People in the Castle by Joan Aiken —The Blue Salt Road by Joanne M. Harris —The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter —A Pocketful of Crows by Joanne M. Harris Explore the amazing worlds of —Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman —The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey Fantasy! From far off lands full of —Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory —Get in Trouble by Kelly Link magic and wonder to the Maguire —Dreams of Distant Shores by Patricia A. -

Unless Otherwise Stated, Place of Publication Is London

Notes Unless otherwise stated, place of publication is London. 1 Introduction 1. Julia Briggs, Night Visitors: The Rise of the English Ghost Story (Faber, 1977), pp. 16-17, 19, 24. 2. See my Christian Fantasy: From 1200 to the Present (Macmillan, 1992). 3. Sidney, An Apologie for Poetrie (1595), repr. in G. Gregory Smith, ed., Elizabethan Critical Essays, 2 vols. (Oxford University Press, 1904), I, 156. 4. See my 'The Elusiveness of Fantasy', in Olena H. Saciuk, ed., The Shape of the Fantastic (Westport: Greenwood, 1990), pp. 54-5. 5. J. R. R. Tolkien, 'On Fairy Stories' (1938; enlarged in his Tree and Leaf (Allen and Unwin, 1964); C. S. Lewis, 'On Science Fiction' (1955), repr. in Lewis, Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, ed. W. Hooper (Bles, 1966), pp. 59-73; Rosemary Jackson, Fantasy: The Literature of Subver sion (Methuen, 1981); Ann Swinfen, In Defence of Fantasy: A Study of the Genre in English and American Literature Since 1945 (Routledge, 1984). 6. Brian Attebery, Strategies of Fantasy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), pp. 12-14. 7. The name is first applied to a literary kind by Herbert Read in English Prose Style (1928); though E. M. Forster had just devoted a chapter of Aspects of the Novel (1927) to 'Fantasy' as a quality of vision. 8. See Brian Stableford, ed., The Dedalus Book of Femmes Fatales (Sawtry, Cambs.: Dedalus, 1992), pp. 20-4. 2 The Origins of English Fantasy 1. See E. S. Hartland, ed., English Fairy and Other Folk Tales (Walter Scott, 1890), pp. x-xxi; Katharine M. -

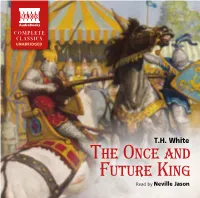

TH White the Once and Future King

COMPLETE CLASSICS UNABRIDGED T.H. White The Once and Future King Read by Neville Jason 1 THE SWORD IN THE STONE 0:31 2 Chapter 1 6:13 3 So it was decided. 7:28 4 The Mews was one of the most important parts of the castle... 6:42 5 Chapter 2 5:52 6 The night fell still... 5:36 7 There was a clearing in the forest... 6:45 8 The Wart went over to the tree... 6:31 9 Chapter 3 6:30 10 Merlyn had a long white beard... 6:44 11 The Wart was so startled... 7:00 12 The vanity-glass vanished... 7:17 13 Chapter 4 7:35 14 Chapter 5 6:24 15 People in those days had rather different ideas... 6:09 16 They crossed the courtyard... 6:45 17 The Wart was on an even keel now... 5:15 18 Mrs Roach held out a languid fin... 5:08 19 The Wart looked, and at first saw nothing… 6:40 20 Chapter 6 6:09 2 21 Kay was frightened by this... 6:28 22 The gore-crow hastened to obey... 6:58 23 The Wart knew he was probably going to be killed... 6:35 24 Instantly Mother Mim was framed in the lighted doorway... 6:40 25 It ought perhaps to be explained... 7:57 26 Chapter 7 6:36 27 The day was cooler than it had been... 7:04 28 While this incantation was going on... 5:27 29 Sir Grummore Grummursum was cantering up.. -

TH White's "Once and Future King"

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 387 TE 001 225 By-Fletcher, Paul F. "The Once and Future King." Pub Date Oct 68 Note- 5p. Journal Cit-Educators Guide to Media & Methods; v5 n2 p54-7 Oct 1968 EDRS Price MF -$0.25 HC-$0.35 Descriptors-Adolescence, *English Instruction, Fables, Fiction, Individual Development. *Legends, Literary Conventions, Literary Genres. Literature, *Literature Appreciation, Mythology. *Novels, Secondary Education. Teaching Techniques, *Twentieth Century Literature Identifiers-*The Once and Future King T.H. White's "Once and Future King" provides an antidote of humor for the pessimism found in many modern literary works. As the title implies, many of the book's themes are timelessthe fruitless quest, the eternal triangle, the conflict of desire and morality, and the opposition of good and evil. Other themes--the fall of the leader and the unifying of diverse elements into political unity--are as timely as a news broadcast. The 20th century, despite its scientific and technological advances, has been dominated by myth; and White's book, with its suffering and aexistential squirm," "is a veritable bellwether for our time." (Suggested teaching activities for a unit on the quest motif are listed. (LH) EMBUICZLIETZIODS Editor FRANK McLAUGHLIN Managing Editor CHARLES FAUCHER Art Director PETER B. RENICH Design RICHARD CLIFF Production Manager R. KENNETH BAXTER Subscription Manager MARY CLAFFEY Motion Pictures JOHN CULKIN Television NED HOOPES Tapes & Records KIRBY JUDD Paperbacks FRANK ROSS Publisher ROGER DAMIO Marketing Director W. BRYCE SMITH 405 Lexington Ave. New York, N.Y. 10017 (212) MU 7-8458 ADVISORY BOARD Barry K. Beyer, Ass't. -

By T. H. White Contents

The Once and Future King by T. H. White Contents THE SWORD IN THE STONE THE QUEEN OF AIR AND DARKNESS THE ILL-MADE KNIGHT THE CANDLE IN THE WIND The critics on T. H. White's THE ONCE AND FUTURE KING "A gay, warm, sad, glinting, rich, mystical, true and beautiful tapestry of human history and human spirit. Read it and laugh. Read it and learn. Read it and be glad you are human." —Minneapolis Tribune "Intensely contemporary and pungent . not only better . and richer for being a retelling, it is also more original ... In fact, there is everything in this great book." —Saturday Review "... should be enormously popular and become one of the curious classics of English literature." —David Garnett Other Books by T. H. White THE BOOK OF MERLYN ENGLAND HAVE MY BONES LETTERS TO A FRIEND THE MAHARAJAH AND OTHER STORIES MISTRESS MASHAM'S REPOSE Incipit Liber Primus THE SWORD IN THE STONE She is not any common earth Water or wood or air, But Merlin's Isle of Gramarye Where you and I will fare. 1 On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays it was Court Hand and Summulae Logicales, while the rest of the week it was the Organon, Repetition and Astrology. The governess was always getting muddled with her astrolabe, and when she got specially muddled she would take it out of the Wart by rapping his knuckles. She did not rap Kay's knuckles, because when Kay grew older he would be Sir Kay, the master of the estate. The Wart was called the Wart because it more or less rhymed with Art, which was short for his real name. -

Changing Role of the Female in Mythically Based Fantastic Literature and Films for Oungy Adults

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 5-31-1996 Changing role of the female in mythically based fantastic literature and films for oungy adults Deborah Dougherty Dietrich Rowan College of New Jersey Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Dietrich, Deborah Dougherty, "Changing role of the female in mythically based fantastic literature and films for oungy adults" (1996). Theses and Dissertations. 2145. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2145 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANGING ROLE OF THE FEMALE IN MYTHICALLY BASED FANTASTIC LITERATURE AND FILMS FOR YOUNG ADULTS by Deborah Dougherty Dietrich A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Masters of Arts Degree in the Graduate Division of Rowan College in School and Public Librarianship 1996 Approved by Professor Date Approved &91 .^ @1996 Deborah Dougherty Dietrich ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Deborah D, Dietrich, Changing Role of the Famale in Mythically Based Fantastic Literature for Young Adults, 1996 Thesis Advisor: Regina Pauly, School and Public Librarianship Psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and C.G. Jung first noted the archetypal symbolism to be found in the dreams, myths and legends of people around the world. Bruno Bertelheim, a disciple of Freud, and renowned mythologist Joseph Campbell applied these principles of universal symbolism to help explain the continuing appeal offary tale, legend and myth m contemporary society.