January 1898

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Formal Language for Palladian Palazzo Façades Represented by A

Buthayna H. Eilouti Research Department of Architectural A Formal Language for Palladian Palazzo Engineering Jordan University of Science Façades Represented by a String and Technology Recognition Device POB 3030 Irbid 22110, JORDAN Abstract. This article represents an effort to reveal a new [email protected] interpretation of the expression ‘the architectural language of Palladian designs’ that is closer to real linguistic paradigms than Keywords: architectural it usually means. Palladian designs exhibit a highly ordered and language, string recognition, well articulated formal language comprised of a finite set of visual study, design vocabulary elements in plan, elevation and volumetric treatment, computation, Palladian together with an implicit set of mathematical rules for the language, finite state automata, arrangement of these rudimentary elements. The scope of this FSA application, façade article is limited to the morphology of the façades of the first morphology nine buildings shown in the second book of Palladio’s treatise, specifically the palazzo designs that he presents in chapter three. The morphology is described in terms of a symbolic encoding system that is represented textually and graphically as a finite state automaton, the concept of which is borrowed from theories of formal languages and computation. The system helps to emphasize commonalities in façade languages and to propose a prototype for generating Palladian palazzo façade designs. The automaton-based encoding system may be developed to function as a base for a computerized façade encoder and decoder. Regular language processing and recognition Studies of formal languages, and their structural and computational representations in linguistics, computer science and related fields as well as their applications, are well- established (e.g., [Chomsky 1964]; [Aho and Ullman 1972]; [Salomaa 1973]; [Harrison 1978]; [Hopcroft and Ullman 1979]; [Linz 1997]; [Revesz 1983]). -

Guida-IRO.Pdf

The Head of Dipartimento di Economia e Management Dear students, Welcome to the Dipartimento di Economia e Management! Our Department is a lively environment where research and teaching live side by side in the areas of economics, business and management studies, mathematics and statistics. Moreover, courses on legal theory and foreign languages applied to economics are provided. In recent years, the Department has particularly increased its international activities, achieving very good results. We have created an International Relations Office, we have more than doubled the number of exchange students and exchange opportunities (Erasmus and overseas), and we have developed an International Programme for undergraduates and graduates, a MSc in Economics and an MBA totally taught in English, and many other international activities. In coming years, we aim to expand the opportunities for studying business, strategy, and marketing in English. This has a double aim: intensify the presence of foreign students in our Department and stimulate our students to live and work in an international context. I hope you will enjoy your stay in Pisa. Prof. Bianchi Martini Index 1. Welcome to Pisa . Welcome to Pisa pag. 6 . How to get to Pisa pag. 7 . A brief history of Pisa pag. 8 . The town and its surroundings pag. 11 . A short tour of Pisa pag. 13 2. IRO International Relations Office . Where we are pag. 18 . Purposes of IRO pag. 19 . International office services pag. 20 3. Academic information . Academic calendar pag. 26 . Study plan pag. 27 . CFU and ECTS credits pag. 28 . Italian marks pag. 29 . How to apply for exams pag. -

3D Mapping the Tower of Pisa

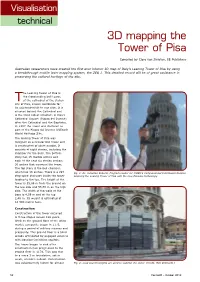

Visualisation technical 3D mapping the Tower of Pisa Compiled by Clare van Zwieten, EE Publishers Australian researchers have created the first ever interior 3D map of Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa by using a breakthrough mobile laser mapping system, the ZEB 1. This detailed record will be of great assistance in preserving the cultural heritage of the site. he Leaning Tower of Pisa is the freestanding bell tower, Tof the cathedral of the Italian city of Pisa, known worldwide for its unintended tilt to one side. It is situated behind the Cathedral and is the third oldest structure in Pisa's Cathedral Square (Piazza del Duomo) after the Cathedral and the Baptistry. In 1987 the tower was declared as part of the Piazza del Duomo UNESCO World Heritage Site. The leaning Tower of Pisa was designed as a circular bell tower and is constructed of white marble. It consists of eight stories, including the chamber for the bells. The bottom story has 15 marble arches and each of the next six stories contain 30 arches that surround the tower. The top story is the bell chamber, which has 16 arches. There is a 297 Fig. 1: Dr. Jonathan Roberts, Program Leader for CSIRO's Computational Informatics Division step spiral staircase inside the tower scanning the Leaning Tower of Pisa with the new Zebedee technology. leading to the top. The height of the tower is 55,86 m from the ground on the low side and 55,70 m on the high side. The width of the walls at the base is 4,09 m and at the top 2,48 m. -

Pisa and Lucca

SHORE EXCURSION BROCHURE FROM THE PORT OF LA SPEZIA DURATION 10 hr Pisa and Lucca TOUR DIFFICULTY EASY MEDIUM HARD iscover the elegant cities of Pisa and Lucca. Your private driver will Dpick you up at the port and take you on the picturesque ride to nearby Pisa where your private guide will be expecting you. Explore the Pisa square of Piazza dei Miracoli, see its Baptistery and the legendary Leaning Tower of Pisa, a UNESCO World Heritage site. After a visit inside the Pisa Duomo to learn about its history, your driver will take you to nearby Lucca, one of Tuscany’s lesser-known gems. After lunch at a selected trattoria, you will tour the town of Lucca which during the Longobard rule in the 11th century was made the capital of Italy. Lucca was famous for its sturdy walls that still encircle the town and its Romanesque architecture. Stroll along its famous ramparts to enjoy magnificent views of the town and surrounding coun- tryside, learn about its precious architecture and the individual spirit of its inhabitants. Enjoy seeing Piazza dell ‘Anfiteatro, Lucca Cathedral and more, and finish with a slice of ‘buccellato,’ Lucca’s signature cake! long with some time for shopping, you’ll fall under the spell of this Aenchanting town. hroughout our Lucca & Pisa shore excursions we’ll try and use scenic Tback roads so that you can fully appreciate the countryside of Tuscany prior to returning to the port of La Spezia and your cruise ship. BUTIQUE TOURS OTHER INFORMATION Highlights Of Your Excursion • This La Spezia shore excursion to Pisa and Lucca • English-speaking driver and private vehicle departs from and returns to your cruise ship. -

1.1 Document on Historical /Architectural/Environmental

Ref. Ares(2016)1596182 - 04/04/2016 D1.1 – Document on historical /archi- tectural/environmental knowledge of the buildings Project Information Grant Agreement Number 646178 Nanomaterials for conservation of European architectural heritage developed by Project Full Title research on characteristic lithotypes Project Acronym NANO-CATHEDRAL NMP-21-2014 Materials-based solutions for protection or preservation of Funding scheme European cultural heritage Start date of the project June, 1 2015 Duration 36 months Project Coordinator Andrea Lazzeri (INSTM) Project Website www.nanocathedral.eu Deliverable Information Deliverable n° D1.1 Deliverable title Document on historical/architectural/environmental knowledge of the buildings WP no. 1 WP Leader Marco Lezzerini (INSTM) CONSORZIO INTERUNIVERSITARIO NAZIONALE PER LA SCIENZA E TECNOLOGIA DIE MATERIALI, Opera della Primaziale Pisana, HDK, UNI BA, Fundación Catedral Contributing Partners Santa María, Dombausekretariat St.Stephan, TU WIEN, Architectenbureau Bressers, Statsbygg Nature public Authors Franz Zehetner, Marco Lezzerini, Michele Marroni, Francesca Signori Marco Lezzerini, Michele Marroni, Francesca Signori, Graziana Maddalena Gianluca De Felice, Anton Sutter, Donatella De Bonis, Roberto Cela Ulrike Brinckmann, Sven Eversberg, Peter Fuessenich, Sophie Hoepner Rainer Drewello Contributors Leandro Camara, Juan Ignacio Lasagabaster Wolfgang Zehetner, Franz Zehetner Andreas Rohatsch, Matea Ban Ignace Roelens, Matthias De Waele, Philippe Depotter, Maarten Van Landeghem Resty Garcia, Yngve Kvame Reviewers Marco Lezzerini, Francesca Signori Contractual Deadline Month 4 (Oct 2015) Delivery date to EC April 4, 2016 1/308 Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (incl. Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (incl. Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for the members of the consortium (incl. -

Learning™ Tower of Pisa

©2003 - v 9/05 611-0385 (30-205) Learning™ Tower of Pisa Warranty and Parts: Stability: How To Use: We replace all defective or miss- If a solid body resting on a base 1. Weigh each slug and measure their ing parts free of charge. All products returns to its original position after it diameter and height. warranted to be free from defect for has been tipped a little, it is said to be 2. Stack the 4 enclosed slugs of dif- 90 days. Does not apply to accident, in "Stable equilibrium." Bodies that are ferent materials in any combination misuse, or normal wear and tear. in stable equilibrium cannot be tipped onto the enclosed 6.4 mm dia steel over unless their center of gravity is pin. first raised. 3. Calculate the center of gravity us- Introduction: There is a simple way of knowing ing the following formula: in advance whether a body, resting on C = M h + M h + M h + M h The world famous Leaning Tower g A 4 B 3 C 2 D 1 a given base, will be stable or topple M + M + M + M of Pisa in Italy presents an interesting A B C D over when released. It the plumb line case study in stability. This tower is 4. To check your calculations, place through its center of gravity falls within 56 meters tall with walls that are 2.6 the assembled tower onto our 40- the boundary of the base on which it meters thick at the base. It is built en- 250 Inclined Plane or a suitable rests, the body will not topple over. -

Branko Mitrović Andrea Palladio's Villa Cornaro in Piombino Dese

Branko Mitroviü Andrea Palladio’s Villa Cornaro in Piombino Dese As for many of Palladio’s buildings, modern surveys of the Villa Cornaro in Piombino Dese do not exist, are incomplete, omit information about important aspects such as the use of the classical orders, or have been published without dimensions indicated in the plans. The analysis presented here is based on a June 2003 survey of the villa made by Steve Wassell, Tim Ross, Melanie Burke, and author Branko Mitroviü. In his treatise, Palladio listed his preferred room types: circular, square or rectangular with length-to-width ratios 2/1, 3/2, 4/3, 5/3 or 2/1. Half a century ago, this kind of speculative search for the comprehensive interpretation of Palladio’s proportional system received great impetus from Rudolf Wittkower’s Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism. It is, however, important to differentiate between the derivation of certain proportional rules and their explanation. Wittkower asserted that the use of ornamentation—and especially the orders—did not matter in Palladio’s design process. Refuting this theory, Mitroviü argues that Palladio, in the early 1550, formulated a very different approach to the use of the orders, combining the principle of preferred room proportions and the use of a columnar system to determine the placement of walls. The proportions of the main sala and porticos are derived on the basis of the proportional rules for the order used; the proportions of the side rooms on the basis of preferred ratios. Ultimately, the result is that the mathematics of the orders became decisive for Palladio’s design principles and the use of proportions from the early 1550s. -

Archaeometric Study of Mortars from the Pisa's Cathedral Square (Italy)

This is a repository copy of Archaeometric study of mortars from the Pisa’s Cathedral Square (Italy). White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131419/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lezzerini, Marco, Raneri, Simona, Pagnotta, Stefano et al. (2 more authors) (2018) Archaeometric study of mortars from the Pisa’s Cathedral Square (Italy). Measurement. ISSN 0263-2241 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2018.05.057 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Archaeometric study of mortars from the Pisa’s Cathedral Square (Italy) Marco LezzeriniA*, Simona RaneriA, Stefano PagnottaA , Stefano ColumbuB , Gianni GallelloC ADepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Pisa, Via S. Maria, 53 – 56126 Pisa, Italy BDepartment of Chemical and Geological Sciences, University of Cagliari, Via Trentino, 51 – 09127 Cagliari, Italy CDepartment of Archaeology, University of York, King’s Manor, YO17EP York, UK * Corresponding author: Marco Lezzerini, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Pisa, Via S. -

Pisa Travel Guide

Pisa Photo: Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock.com Pisa is strategically located in the central part of Italy, at only 12 km from the Ligurian Sea, 20 km from the harbour of Livorno and the ferries heading to the Elba Island, Sardinia and Corsica, and 80 km from Florence. This city is closely associated with the Leaning Tower, but it also preserves, along with the whole complex of Piazza dei Miracoli - UNESCO World Heritage Site - and its medieval centre, numerous masterpieces of architecture and medieval history. The area around Pisa is also excellent for farm holidays, trekking, beaches and water sports on the Versilian coast. RossHelen/Shutterstock.com Top 5 Pisa Cathedral and Baptistery Pisa Baptistery (Battistero di San Giovanni) shares grounds with Pisa Duomo ... Via Aurelia (Aurelia Stree... This street played an important role in times of the ancient Roman Empire, t... The Leaning Tower Elena Korn/Shutterstock.com One of the most outstanding architectural structures of medieval Europe (par... Botanical Garden and Museum The Botanical Garden and Museum (Orto e Museo Botanico) was established in 1... Camposanto The Italian word "Camposanto" (Holy Yard) - which is a synonym of "cemetery"... Virginia Schianini/Shutterstock.com Updated 10 May 2021 Destination: Pisa Publishing date: 2021-05-10 THE CITY km), Volterra (65 km), San Gimignano (80 km) and Florence (105 km). DO & SEE arkanto/Shutterstock.com You say Pisa and you immediately think of the Leaning Tower, one of the most famous FredP/Shutterstock.com monuments in the world. But Pisa is much more than just its tower, it is also home to the The boat service in Pisa will let you enjoy the extraordinary complex of buildings known as the architectural scenery of the Lungarni, or the Piazza dei Miracoli (Square of Miracles), with its natural beauty of the nearby San Rossore magnicent cathedral and baptistery. -

Palladiano Nerario Immaginata L’Iti Ascoprire Accompagnare Vogliamo Piccola Vi Con Questa Guida Genio Dell’Architettura

le nostre guide e i siti www.discoverpalladio.org e www.vicenzae.org. e www.discoverpalladio.org siti i e guide nostre le www.palladio2008.info – www.cisapalladio.org – www.palladio2008.info www.vicenzae.org – www.vicenzabooking.com – www.vicenzae.org cenza, invitandovi a scoprire quindi l’itinerario delle ville attraverso attraverso ville delle l’itinerario quindi scoprire a invitandovi cenza, icenza V Camera di Commercio di Camera e.mail: [email protected] e.mail: - Vi di storico centro del immaginata nell’armonia palladiano nerario - l’iti scoprire a accompagnare vogliamo vi guida piccola questa Con ville della provincia, tutti attribuite al genio dell’architettura. dell’architettura. genio al attribuite tutti provincia, della ville del Patrimonio Mondiale 23 monumenti del suo centro storico e 16 16 e storico centro suo del monumenti 23 Mondiale Patrimonio del mente riconosciuta come la città del Palladio iscrivendo nella Lista Lista nella iscrivendo Palladio del città la come riconosciuta mente - universal è l’Unesco, decretato ha come Vicenza, certa: è cosa Una mitologico, comunque sovrannaturale. comunque mitologico, ad affidargli il nome di Palladio, fosse un angelo o un personaggio personaggio un o angelo un fosse Palladio, di nome il affidargli ad Ideazione e testi a cura di Vicenza è sicuramente ragione Gian Giorgio Trissino, il suo grande mentore, mentore, grande suo il Trissino, Giorgio Gian ragione sicuramente DI VICENZA DI PROVINCIA il luogo della morte e perfino il luogo della sua sepoltura. Ha avuto avuto Ha sepoltura. sua della luogo il perfino e morte della luogo il la residenza coniugale di Vicenza, i lineamenti del volto, le cause e e cause le volto, del lineamenti i Vicenza, di coniugale residenza la i natali. -

The Munich Antiquarium

Chapter 8 The Munich Antiquarium 8.1 The Commission By the time Strada’s house had neared some form of completion, he became involved in the one architectural project for which designs in his hand have been preserved, the Antiquarium of the Munich Residenz. It is moreover the only building for the design of which he claimed some credit, in his dedi- cation of his 1575 edition of Caesar to the patron of the Antiquarium, Duke Albrecht v of Bavaria.1 The planning of this huge building was the direct conse- quence of the campaign of acquisition of antique sculpture undertaken by the Duke in the 1560s. This campaign was stimulated and coordinated by Strada’s old patron and friend Hans Jakob Fugger: as we have seen, at Fugger’s clamor- ous bankruptcy in 1564, the Duke had taken over Fugger’s debts in exchange for his library and his collection of antiquities, which became the foundation of the collection brought together at Munich.2 It was natural that Strada, who had been Fugger’s principal agent in the acquisition of antiquities, would again be asked to contribute his expertise: his trips to Italy to acquire additional sculp- tures for the Duke have been mentioned above. And it was equally natural, in view of his architectural know-how, that he would be asked to advise about the best way to display these acquisitions. Initially it was planned to house the antiquities in the Duke’s Kunstkam- mer, located on the first floor of a building that itself was without precedent in Germany. -

Private Palaces, Villas, and Gardens of Venice and the Veneto

Private Palaces, Villas, and Gardens of Venice and the Veneto Sponsored by Institute of Classical Architecture & Art ƒ Arranged by Pamela Huntington Darling, Exclusive Cultural Travel Programs Sunday, October 9 to Sunday, October 16, 2011 7 days and 7 nights Fascinating Venice and Veneto, priding a rich heritage of art, architecture, and décor, are ultimately unique. Beyond the usual tourist ventures, there is a secret Venice and Veneto, known to Venetians of nobility and the privileged few. As a participant of this exclusive program, you will have the opportunity to join an intimate group of discerning travelers and be invited by members of the esteemed cultural and social world of the Veneto and Venice to private visits, luncheons, cocktail receptions, and dinners in magnificent villas and palazzi of Venetian nobility, rarely opened to outside visitors, accompanied by a historian of the Venetian community. Following the 500th anniversary of the birth of the great Italian classical architect Andrea Palladio, we will enjoy seven days of private visits and receptions in the most important Palladian villas in the Veneto and in palazzi in Venice, with their proprietors, specially organized for you. We will observe the development of Venetian art, décor and architecture through its beginnings to the emergence of the Renaissance and the peak of Venetian heritage in the 16th and the 18th centuries. Countess Giuliana di Thiene, expert lecturer and member of Venetian nobility, will guide us throughout this unique cultural travel program to the Veneto region and to Venice. For the first three nights, we will stay in the picturesque, medieval town of Asolo, “city of a thousand landscapes”, set on gentle hills that inspired Titian and Giorgione, offering stunning views of the countryside.