Sarah L. Mitchell Dphil the University of York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Preface and Introduction

Marine Aggregate Extraction: Approaching Good Practice in Environmental Impact Assessment 1 PREFACE AND INTRODUCTION This publication and references within it to any methodology, process, service, manufacturer, or company do not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister or the Minerals Industry Research Organisation. Gravel image reproduced courtesy of BMAPA Hamon grab © MESL-Photo Library Boomer system © Posford Haskoning Wrasse image reproduced courtesy of Keith Hiscock (MarLIN) Aerial Plume courtesy of HR Wallingford Coastline © Posford Haskoning Fishing vessels © Posford Haskoning Dredger image courtesy of BMAPA Beam trawl © MESL-Photo Library ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Posford Haskoning project team would like to thank the following members of the Expert Panel, established for this project, for all their invaluable advice and comments: Dr Alan Brampton (HR Wallingford Ltd) Dr Tony Firth (Wessex Archaeology) Professor Richard Newell Ali McDonald (Anatec UK Ltd) (Marine Ecological Surveys Ltd) Dr Tony Seymour (Fisheries Consultant) Dr Ian Selby (Hanson Aggregates Marine Ltd) In addition to this expert panel, key sections of the report were contributed by the following, to whom thanks are again extended: • Dr Peter Henderson (Pisces Conservation Ltd) • Dr Paul Somerfield (Plymouth Marine Laboratory) • Dr Jeremy Spearman (HR Wallingford Ltd) The project has also benefited considerably from an initial review by the following organisations. The time and assistance of these reviewers was greatly appreciated: -

Template:Ælfgifu Theories Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Template:Ælfgifu Theories from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/6/2016 Template:Ælfgifu theories Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Template:Ælfgifu theories From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Family tree, showing two theories relating Aelgifu to Eadwig, King of England Æthelred Æthelwulf Mucel King of Osburh Ealdorman Eadburh Wessex of the Gaini ?–839858 fl. 867895 Alfred Æthelred I the Great Æthelbald Burgred Æthelberht Æthelwulf Æthelstan King of King of the King of King of Æthelswith King of Ealhswith Ealdorman King of Kent Wessex Anglo Wessex Mercia d. 888 Wessex d. 902 of the Gaini ?–839855 c.848–865 Saxons ?–856860 ?–852874 ?–860865 d. 901 871 849–871 899 Edward the Elder Æthelfrith King of the (2)Ælfflæd Ealdorman Æthelhelm Æthelwold (1)Ecgwynn (3)Eadgifu Æthelgyth Anglo fl. 900s of S. Mercia fl. 880s d. 901 fl. 890s x903–966x fl. 903 Saxons 910s fl. 883 c.875–899 904/915 924 unknown Æthelstan Æthelstan Edmund I Eadric Eadred Ælfstan HalfKing Æthelwald King of King of Ealdorman King of Ealdorman Ealdorman Ealdorman unknown Æthelgifu the English the English of Wessex the English of Mercia of East of Kent c.894–924 921–939 fl. 942 923946955 fl. 930934 Anglia fl. 940946 939 946 949 fl. 932956 Eadwig Edgar I Æthelwald Æthelwine AllFair the Peaceful Æthelweard Ælfgifu Ealdorman Ealdorman King of King of historian ? Ælfweard Ælfwaru fl. 956x957 of East of East England England d. c.998 971 Anglia Anglia c.940955 c.943–959 d. 962 d. 992 959 975 Two theories for the relationship of Ælfgifu and Eadwig King of England, whose marriage was annulled in 958 on grounds of consanguinuity. -

Wessex and the Reign of Edmund Ii Ironside

Chapter 16 Wessex and the Reign of Edmund ii Ironside David McDermott Edmund Ironside, the eldest surviving son of Æthelred ii (‘the Unready’), is an often overlooked political figure. This results primarily from the brevity of his reign, which lasted approximately seven months, from 23 April to 30 November 1016. It could also be said that Edmund’s legacy compares unfavourably with those of his forebears. Unlike other Anglo-Saxon Kings of England whose lon- ger reigns and periods of uninterrupted peace gave them opportunities to leg- islate, renovate the currency or reform the Church, Edmund’s brief rule was dominated by the need to quell initial domestic opposition to his rule, and prevent a determined foreign adversary seizing the throne. Edmund conduct- ed his kingship under demanding circumstances and for his resolute, indefati- gable and mostly successful resistance to Cnut, his career deserves to be dis- cussed and his successes acknowledged. Before discussing the importance of Wessex for Edmund Ironside, it is con- structive, at this stage, to clarify what is meant by ‘Wessex’. It is also fitting to use the definition of the region provided by Barbara Yorke. The core shires of Wessex may be reliably regarded as Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berk- shire and Hampshire (including the Isle of Wight).1 Following the victory of the West Saxon King Ecgbert at the battle of Ellendun (Wroughton, Wilts.) in 835, the borders of Wessex expanded, with the counties of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Essex passing from Mercian to West Saxon control.2 Wessex was not the only region with which Edmund was associated, and nor was he the only king from the royal House of Wessex with connections to other regions. -

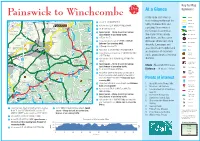

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

1906 BNJ 3 35.Pdf

INDEX. A. Account, the shilling a money of, prior to the reign of Henry VII., 304. A, characteristics of the letter, on the Acsian = "to ask" in early MS., 87. Ohsnaforda pennies, 72-74. Adalhard, abbot of Corbie, 89. ,, the unbarred variety of the letter, Advocates, Faculty of, and the Jacobite 72 et seq. Medal, 247. „ varieties of the letter, 72-74. yE, the ligatured letter on the Ohsna- Abbreviations on Roman coins, sugges- forda coins, 74, 75. tions for the interpretation of certain, /Elfred, forgery of Oxford type of, 28 r. 3r> 32- ,, halfpenny of Oxford type of, 281. Aberdeen, find of billon pieces of Francis ^Enobarbus pays his soldiers with leather and Mary near, 330, 406, money, 313. 407. ^Eschines and the use of leather money, ,, find of coins temp. Alex- 312. ander III., Robert Bruce ^Ethelred I., coins of, 66. and John Baliol at, 333, 407. ,, find of coins of, in the ,, find of coins temp., Edward I., Thames, at Waterloo II. and III. at, 332 et seq., Bridge, 385. 406, 407. „ II., coins of, 120, 122, 123, ,, find of foreign sterlings at, 124, 125, 126, 128, 134, T35> x36> r37, 138, 140, 333. 334- 141, 142, 145, 146, 147.. ,, find of lions or hardheads 148, 149, 150, 151, i:,3, temp. Mary and Francis in, !54, 156. 15 7> 159, 161, 330, 406, 407. 162, 163, 388. „ find, painting of the bronze ,, ,, helmet on the coins of, pot containing the, 403. 297. „ finds of coins temp. Edward I. „ ,, penny of, the earliest coin and Alexander III. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering -

Vocabulary, Grammar and Punctuation

English Appendix 2: Vocabulary, grammar and punctuation Year 1 The following should be taught at year 1: Punctuation Separation of words with finger spaces. The use of capital letters, full stops, question marks and exclamation marks in sentences. Capital letter for proper nouns (names of people, places, days of the week). Capital letter for the personal pronoun I Grammar and Vocabulary The use of regular plural noun suffixes. e.g. adding s or es. (dog–dogs and wish– wishes ) Adding suffixes to words where there is no change to the spelling of the root word:e.g. root word–help becomes helping, helper, helped. Using and understanding how the prefix un changes the meaning of verbs and adjectives. e.g. kind– unkind, tie–untie. How words can make simple sentences. Join words and clauses with and. Grammatical terms that Letter children should know Capital letter Full stop word Singular and plural Sentence Punctuation Question mark Exclamation mark Link to SPaG progression Y1 Sentence structures Examples document Join words and clauses with Write 2 simple sentences joined with I can see the dog and the cat. and and because and and because. 1A sentences I can see the scruffy dog. One adjective before the noun Year 2 The following should be taught at year 2, ensuring that year 1 content is secure. Punctuation The use of capital letters, full stops, question marks and exclamation marks in sentences. The use of commas to separate items in a list The use of apostrophes for omission. e.g. did not – didn’t The use of apostrophe to show singular possession in nouns e.g. -

National Statistics Postcode Lookup User Guide

National Statistics Postcode Lookup User Guide Edition: May 2018 Editor: ONS Geography Office for National Statistics May 2018 NSPL User Guide May 2018 A National Statistics Publication Copyright and Reproduction National Statistics are produced to high professional standards Please refer to the 'Postcode products' section on our Licences set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics. They are page for the terms applicable to these products. produced free from political influence. TRADEMARKS About Us Gridlink is a registered trademark of the Gridlink Consortium Office for National Statistics and may not be used without the written consent of the Gridlink The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is the executive office of Programme Board. the UK Statistics Authority, a non-ministerial department which The Gridlink logo is a registered trademark. reports directly to Parliament. ONS is the UK government’s single largest statistical producer. It compiles information about OS AddressBase is a registered trademark of Ordnance the UK’s society and economy, and provides the evidence-base Survey (OS), the national mapping agency of Great Britain. for policy and decision-making, the allocation of resources, and Boundary-Line is a trademark of OS, the national mapping public accountability. The Directors General of ONS report agency of Great Britain. directly to the National Statistician who is the Authority's Chief Executive and the Head of the Government Statistical Service. Pointer is a registered trademark of Land and Property Services, an Executive Agency of the Department of Finance and Personnel Government Statistical Service (Northern Ireland). The Government Statistical Service (GSS) is a network of professional statisticians and their staff operating both within the ONS and across more than 30 other government departments and agencies. -

INCOME TAX in COMMON LAW JURISDICTIONS: from the Origins

This page intentionally left blank INCOME TAX IN COMMON LAW JURISDICTIONS Many common law countries inherited British income tax rules. Whether the inheritance was direct or indirect, the rationale and origins of some of the central rules seem almost lost in history. Commonly, they are simply explained as being of British origin without further explanation, but even in Britain the origins of some of these rules are less than clear. This book traces the roots of the income tax and its precursors in Britain and in its former colonies to 1820. Harris focuses on four issues that are central to common law income taxes and which are of particular current relevance: the capitalÀrevenue distinction, the taxation of corporations, taxation on both a source and residence basis, and the schedular approach to taxation. He uses an historical per- spective to make observations about the future direction of income tax in the modern world. Volume II will cover the period 1820 to 2000. PETER HARRIS is a solicitor whose primary interest is in tax law. He is also a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Law of the University of Cambridge, Deputy Director of the Faculty’s Centre for Tax Law, and a Tutor, Director of Studies and Fellow at Churchill College. CAMBRIDGE TAX LAW SERIES Tax law is a growing area of interest, as it is included as a subdivision in many areas of study and is a key consideration in business needs throughout the world. Books in this Series will expose the theoretical underpinning behind the law to shed light on the taxation systems, so that the questions to be asked when addressing an issue become clear. -

Celtic Sea Case Study Governance Analysis Finding Sanctuary and England’S Marine Conservation Zone Process

MESMA Work Package 6 Celtic Sea Case Study Governance Analysis Finding Sanctuary and England’s Marine Conservation Zone process Louise M. Lieberknecht Wanfei Qiu, Peter J. S. Jones Department of Geography, University College London Report published in January 2013 Table of Contents Cover Note ..........................................................................................................................................7 About the main author (statement of positionality) ......................................................................7 Acknowledgements.........................................................................................................................8 About the references in this report ................................................................................................8 1. Context............................................................................................................................................9 1.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................9 1.1.1 Introduction to the case study...........................................................................................9 1.1.2 History of Finding Sanctuary..............................................................................................9 1.1.3 The Finding Sanctuary region...........................................................................................12 1.1.4 Finding Sanctuary within the context of -

Identifying Outdoor Assembly Sites in Early Medieval England John Baker1, Stuart Brookes2 1The University of Nottingham, Notting

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham Identifying outdoor assembly sites in early medieval England John Baker1, Stuart Brookes2 1The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2University College London, London, United Kingdom Correspondence to: Stuart Brookes, UCL Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom. Email: [email protected] 1 Venues of outdoor assembly are an important type of archaeological site. Using the example of early medieval (Anglo-Saxon; 5th–11th centuries A.D.) meeting places in England we describe a new multidisciplinary method for identifying and characterizing such sites. This method employs place name studies, field survey, and phenomenological approaches such as viewshed, sound- mark, and landscape character recording. While each site may comprise a unique combination of landscape features, it is argued that by applying criteria of accessibility, distinctiveness, functionality, and location, important patterns in the characteristics of outdoor assembly places emerge. Our observations relating to Anglo-Saxon meeting places have relevance to other ephemeral sites. Archaeological fieldwork can benefit greatly by a rigorous application of evidence from place name studies and folklore/oral history to the question of outdoor assembly sites. Also, phenomenological approaches are an important in assessing the choice of assembly places by past peoples. Keywords: early medieval England, hundreds, assembly places, place names, temporary sites, judicial governance, phenomenology 2 Introduction Temporary, popular gatherings in outdoor settings are common in societies of the past and present. Fairs, political rallies, festivals, sporting events, camps, theater, and battles are frequent events, but most leave few physical traces for archaeologists to recover.