Building Future Forests: Politics, Ecology, and the Co-Production Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skt Sigma Kappa Triangle Vol 5

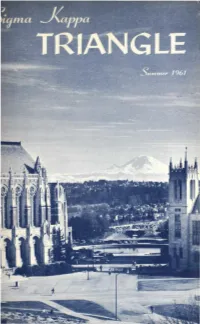

"We're on the University Kick" was the Homecoming Float of Gamma Lambda at East Tennessee State. KING, AX, DEANNA COFFMAN, r A, with her cousin, sang "I'm just a Bird in Tennessee Ernie Ford, when he came to Ten a Gilded Cage" with nessee to cut a record with his home-folk. dance routines and won Deanna is president of Delta Omicron and THETAs top prize second place in George was elected to Who's Who from East Tennes town variety show. entry at Illinois YWCA see State. Show, an annual event. DLUME 55 UMBER 2 SUMMER 1961 Official Magazine of Sigma Kappa Sorority Founded at Colby College, November, 1874 ~······························Editor-in-Chief, FRANCES WARREN BAKER (Mrs, James Stannard Baker, 433 Woodlawn Ave., Glencoe, Ill.) lumruz Editor--Beatrice Strait Line~ (Mrs. Harold' B. Lines), 234 Salt Springs Rd., Syracuse 3, N.Y. 'ollere Editer~-Jean Bandslev Coleman (Mrs. John Coleman), Meadow Estatu, Wheeling, W.Va. Anna Weaver Booske (Mrs. Henry Booske) , 1617 Zarker Rd., Lancaster, Pa. utineu M•n•ller--Margaret Hazlett Taegart (Mrs. E. D. Taggart), 3433 Washineton Blvd., Indianapolis, Ind. ~······························ FRONT COVER: "Rainier Vista" at the University of Washington in Seattle, with Suzzallo library (left) and administration building (right). The University, among the 15 largest universities in the nation with a day-school enrollment of over 18,000 and a faculty o£ 1,150, is celebrating its Centennial this year. Our Mu chapter celebrated its 50th anniversary. 3 Mu Celebrates 50 Years of Success at Washington 8 Council -

Tennis Courts, One Large Multi‐Purpose Indoor Facility, and Over 9,000 Acres of Open Space Will Also Be Needed

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The contribution of the following individuals in preparing this document is gratefully acknowledged: City Council Robert Cashell, Mayor Pierre Hascheff, At‐Large Dan Gustin, Ward One Sharon Zadra, Ward Two Jessica Sferrazza, Ward Three Dwight Dortch, Ward Four David Aiazzi, Ward Five City of Reno Charles McNeely, City Manager Susan Schlerf, Assistant City Manager Julee Conway, Director of Parks, Recreation & Community Services John MacIntyre, Project Manager Jaime Schroeder, Senior Management Analyst Mary Beth Anderson, Interim Community Services Manager Nick Anthony, Legislative Relations Program Manager John Aramini, Recreation & Park Commissioner Angel Bachand, Program Assistant Liz Boen, Senior Management Analyst Tait Ecklund, Management Analyst James Graham, Economic Development Program Manager Napoleon Haney, Special Assistant to the City Manager Jessica Jones, Economic Development Program Manager Sven Leff, Recreation Supervisor Mark Lewis, Redevelopment Administrator Jeff Mann, Park Maintenance Manager Cadence Matijevich, Special Events Program Manager Billy Sibley, Open Space & Trails Coordinator Johnathan Skinner, Recreation Manager Suzanna Stigar, Recreation Supervisor Joe Wilson, Recreation Supervisor Terry Zeller, Park Development Planner University of Nevada, Reno Cary Groth, Athletics Director Keith Hackett, Associate Athletics Director Scott Turek, Development Director Washoe County School District Rick Harris, Deputy Superintendent 2 “The most livable of Nevada cities; City Manager’s Office the focus of culture, commerce and Charles McNeely tourism in Northern Nevada.” August 1, 2008 Dear Community Park & Recreation Advocate; Great Cities are characterized by their parks, trails and natural areas. These areas help define the public spaces; the commons where all can gather to seek solace, find adventure, experience harmony and re’create their souls. The City of Reno has actively led the community in enhancing the livability of the City over the past several years. -

Download Press Release (.Pdf), 222.76 Kb

PRESS RELEASE _______________________________________________________________________ Waiblingen, September 19, 2017 STIHL develops future technology and records double-digit growth Triple-digit unit sales growth in cordless segment boosts turnover growth World firsts: STIHL TS 440 cut-off machine and robotic mower VIKING iMow TeaM STIHL sets new standards with electronic fuel injection in gasoline chainsaws The turnover of the STIHL Group in the current year increased by 11.9 percent to EUR 2.7 billion in the period from January to August. Had foreign exchange rates remained unchanged, growth would have been 10.7 percent. “This double-digit plus has upped the pace of our projected growth. In cordless products in particular we have achieved an exceptionally strong increase in unit sales”, explained STIHL executive board chairman Dr. Bertram Kandziora at the company’s autumn press conference in Wai- blingen. “We have the capacity to continue growing strongly and want to consolidate our technology leadership”, stressed Dr. Kandziora. STIHL is currently researching and developing products not only in the areas of battery technology and connected prod- ucts, but also wants to set new standards in gasoline products: “At present we are working on the world’s first chainsaw with electronically controlled fuel injection”, said the executive board chairman. Further world firsts are the STIHL TS 440 cut-off ma- chine with integrated Quickstop wheel brake and the intelligently interconnected robotic mower VIKING iMow TeaM. Worldwide growth – increased demand for gasoline and cordless products The U.S. market and Western Europe were the main growth engines for the STIHL Group in the first eight months of this year. -

Restoring Forests for the Future: Profiles in Climate-Smart Restoration on America's National Forests

RESTORING FORESTS for the FUTURE Profiles in climate-smart restoration on America’s National Forests Left: Melissa Jenkins Front cover: Kent Mason Back cover: MaxForster. Contents Introduction. ............................................................................................................................................2 This publication was prepared as part of a collaboration among American Forests, National Wildlife Federation and The Nature Conservancy and was funded through a generous grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Principles for Climate-Smart Forest Restoration. .................................................................3 Thank you to the many partners and contributors who provided content, photos, quotes and Look to the future while learning from the past. more. Special thanks to Nick Miner and Eric Sprague (American Forests); Lauren Anderson, Northern Rockies: Reviving ancient traditions of fire to restore the land .....................4 Jessica Arriens, Sarah Bates, Patty Glick and Bruce A. Stein (National Wildlife Federation); and Eric Bontrager, Kimberly R. Hall, Karen Lee and Christopher Topik (The Nature Conservancy). Embrace functional restoration of ecological integrity. Southern Rockies: Assisted regeneration in fire-scarred landscapes ............................ 8 Editor: Rebecca Turner Montana: Strategic watershed restoration for climate resilience ................................... 12 Managing Editor: Ashlan Bonnell Writer: Carol Denny Restore and manage forests in the context of -

Land Use Policy Tree Farms

Land Use Policy 26 (2009) 545–550 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Land Use Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landusepol Tree farms: Driving forces and regional patterns in the global expansion of forest plantations Thomas K. Rudel ∗ Department of Human Ecology, Rutgers University, 55 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, United States article info abstract Article history: People have planted trees in rural places with increasing frequency during the past two decades, but the Received 21 November 2007 circumstances in which they plant and the social forces inducing them to plant remain unclear. While Accepted 7 August 2008 forests that produce wood for industrial uses comprise an increasing number of the plantations, most of the growth has occurred in Asia where plantations that produce wood for local consumption remain Keywords: important. Explanations for these trends take economic, political, and human ecological forms. Growth Forest plantations in urban and global markets for forest products, coupled with rural to urban migration, may spur the Forest transition conversion of fields into tree farms. Government programs also stimulate tree planting. These programs Tree farms Rural to urban migration occur frequently in nations with high population densities. Quantitative, cross-national analyses suggest that these forces combine in regionally distinctive ways to promote the expansion of forest plantations. In Africa and Asia plantations have expanded most rapidly in nations with densely populated rural districts, rural to urban migration, and government policies that promote tree planting. In the Americas and Oceania plantations have expanded rapidly in countries with relatively stable rural populations, low densities, and extensive tracts of land in pasture. -

Forest--Savanna Transition Zones

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Biogeosciences Discuss., 11, 4591–4636, 2014 Open Access www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/11/4591/2014/ Biogeosciences BGD doi:10.5194/bgd-11-4591-2014 Discussions © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 11, 4591–4636, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Biogeosciences (BG). Forest–savanna Please refer to the corresponding final paper in BG if available. transition zones Structural, physiognomic and E. M. Veenendaal et al. aboveground biomass variation in Title Page savanna-forest transition zones on three Abstract Introduction continents. How different are Conclusions References co-occurring savanna and forest Tables Figures formations? J I E. M. Veenendaal1, M. Torello-Raventos2, T. R. Feldpausch3, T. F. Domingues4, J I 5 3 2,25 3,6 7 8 F. Gerard , F. Schrodt , G. Saiz , C. A. Quesada , G. Djagbletey , A. Ford , Back Close J. Kemp9, B. S. Marimon10, B. H. Marimon-Junior10, E. Lenza10, J. A. Ratter11, L. Maracahipes10, D. Sasaki12, B. Sonké13, L. Zapfack13, D. Villarroel14, Full Screen / Esc M. Schwarz15, F. Yoko Ishida6,16, M. Gilpin3, G. B. Nardoto17, K. Affum-Baffoe18, L. Arroyo14, K. Bloomfield3, G. Ceca1, H. Compaore19, K. Davies2, A. Diallo20, Printer-friendly Version N. M. Fyllas3, J. Gignoux21, F. Hien20, M. Johnson3, E. Mougin22, P. Hiernaux22, Interactive Discussion T. Killeen14,23, D. Metcalfe8, H. S. Miranda17, M. Steininger24, K. Sykora1, M. I. Bird2, J. Grace4, S. Lewis3,26, O. L. Phillips3, and J. Lloyd16,27 4591 -

July 11,1912

The Republican Journal. 84 BELFAST, MA1SE. THURSDAY, JULY 1912. U>lp1E 11, ^UMBFR 2ft of Today’s Journal. decorated auto driven by Donald contents The Fourth in Belfast. Clark, in ery, Miss Louise Hazeltine, Mita Margarel which rode the following members PERSONAL. of the of- White, Mias Katherine C. Quimby and Mias PERSONAL. Inn Opened... Visiting i fice force: personalT ! v rthport The Weather was fine and the Celebration Mias Ida Ames, Miss Ruth Ather- were dinner 1 .The Fourth in Belfast, Margaret Van Vorhees gueata; Fa v •,men. ton, Miss Verna Randall and Miss Annie Boardman of Bangor is Game..Personal..News a Success. Marian Rhoades. several of the officers visiting Mrs. Sallie Durham Hanshue arrived from ij Innings later, accompanied by relatives in Belfast. Mr. and Mrs. James D. Tucker “The The Belfast Opera House. Boston last of Boston are of the Granges. night before” was less disturbing than Manager Walter attending the ball in the Opera House. Friday to visit relatives. J. Clifford’s Miss visiting friends in Belfast. >n County “Barrens.’' (Edi- on some former occasions. of the Ford car, prettily decorated and small at din- Julia Sullivan of Waltham, Mass., is the gt j Ringing There were many other parties Percy Poor of.Providence, R. I, arrived last r; New Record...Coffee Im- driven Mr. Clifford. The of Mrs. E. Miss Abbie 0. Stobbard has church bells at 3.30 a. m. on the mora- by occupants were in guest L. Cook. returned from a United States..Bastel- I began ners and teas during the ship’s stay port Thursday to visit Dr. -

November 3, 2016 Charlottetown, PEI for IMMEDIATE DISTRIBUTION

November 3, 2016 Charlottetown, PEI FOR IMMEDIATE DISTRIBUTION SHARP AXES - POWERFUL CHAIN SAWS – PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES THE STIHL TIMBERSPORTS CANADIAN SERIES IS COMING TO TOWN! The STIHL TIMBERSPORTS Canadian Series announces the Canadian Champions Trophy. You have seen it on TV, now come experience it LIVE! As part of Canada’s 150th anniversary celebration, the top Professional Axe-Men in the country will head to town for an event never seen before in the Island and that will have spectators at the edge of their seats from beginning to end. The STIHL TIMBERSPORTS Champions Trophy is the “Master’s Cup” of the sport and is the most coveted event in the Canadian tour. This invitational event features the top eight athletes from the Canadian Championship – the ones that battled the hardest to the top of the Canadian ranking in 2016. "Thanks to the efforts of our sport tourism initiative, SCORE, Canada Day weekend in the Birthplace of Confederation is sure to be an exhilarating experience in 2017 as we welcome the STIHL TIMBERSPORTS Canadian Champions Trophy to Charlottetown," said Mayor Clifford Lee. "With the picturesque Charlottetown waterfront as a backdrop to this ultimate extreme sport, residents, visitors, and TSN viewers will be wildly entertained by this not to be missed Major League of logger sports." The Champions Trophy features four out of the six STIHL TIMBERSPORTS disciplines in a back to back relay format without taking a break. Two athletes at a time will go head to head; winner moves on to the next round, losing athlete is knocked out! The competition starts with the Stock Saw discipline, in which the athlete must cut a disc of wood, a “cookie”, from a log with one downward cut, followed by the Underhand Chop, which simulates chopping a felled tree. -

Livelihood Transition and Adaptive Bamboo Forest Management: a Case Study in Salakpra Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand

Mianmit et al., J Biodivers Manage Forestry 2018, 7:1 DOI: 10.4172/2327-4417.1000193 Journal of Biodiversity Management & Forestry Research Article a SciTechnol journal abrogated, creating an area of about 77.65km2 to be used for the Livelihood Transition and Srinakarin dam-building project and preparation for resettlement [2]. This project directly affected SPWS because bamboo cutting was Adaptive Bamboo Forest the main cash income of the reservoir refugees. The process of the development policy from the past to the present time has affected the Management: A Case Study in local people’s livelihoods and bamboo forest utilization in SPWS. Salakpra Wildlife Sanctuary, Thus, focusing on the occupational change of bamboo cutters and adaptive bamboo forest management by locals based on modified Thailand traditional knowledge, the livelihood transition and its relationship Nittaya Mianmit1*, Rachanee Pothitan1 and Shinya Takeda2 with bamboo in natural forest is investigated. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to examine a case of forest transition in Thailand. Forest transition refers to the change from shrinking to expanding Abstract forest focusing on the changing forest area [3-8] owever, the forest transition theory by Mather pointed that not only forest area changes The connection between livelihood transition and adaptive bamboo but forest transition also implies a changeover to a different system of forest management was investigated in a village adjoining Salakpra forest use or management [3]. They defined Thailand as a non-forest Wildlife Sanctuary, Kanchaburi Province, where three species of bamboo—Dendrocalamus membranaceus, Bambusa bambos, transition country in Asia [9], resulting in a reduction of forestland and Thyrsostachys siamensis—were collected by villagers. -

Deforestation and Economic Growth Trends on Oceanic Islands Highlight the Need for Meso-Scale Analysis and Improved Mid-Range Theory in Conservation

Copyright © 2020 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Bhatia, N., and G. S. Cumming. 2020. Deforestation and economic growth trends on oceanic islands highlight the need for meso-scale analysis and improved mid-range theory in conservation. Ecology and Society 25(3):10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11713-250310 Research Deforestation and economic growth trends on oceanic islands highlight the need for meso-scale analysis and improved mid-range theory in conservation Nitin Bhatia 1 and Graeme S. Cumming 1 ABSTRACT. Forests both support biodiversity and provide a wide range of benefits to people at multiple scales. Global and national remote sensing analyses of drivers of forest change generally focus on broad-scale influences on area (composition), ignoring arrangement (configuration). To explore meso-scale relationships, we compared forest composition and configuration to six indicators of economic growth over 23 years (1992–2015) of satellite data for 23 island nations. Based on global analyses, we expected to find clear relationships between economic growth and forest cover. Eleven islands lost 1 to 50% of forest cover, eight gained 1 to 28%, and four remained steady. Surprisingly, we found no clear relationship between economic growth trends and forest-cover change trajectories. These results differ from those of global land-cover change analyses and suggest that conservation-oriented policy and management approaches developed at both national and local scales are ignoring key meso-scale processes. Key Words: deforestation; economic indicators; land-cover change; land-use change; landscape composition; landscape configuration; remote sensing INTRODUCTION Cumming et al. -

Fire in the Black Hills Forest-Grass Ecotonel

Fire in the Black Hills Forest-Grass Ecotonel F. ROBERT GARTNER AND WESLEY W. THOMPSON2 Associate Professor of Range Ecology and Range Research Assistant, Animal Science Department, West River Agricultural Research and Extension Center of South Dakota State University, 801 San Francisco Street, Rapid City, SD 57701 INTRODUCTION SOUTH Dakota is located in the geographical center of the North American continent, equidistant from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and midway between the North Pole and the equa tor (United States Dept. Interior 1967). The Black Hills are situated along the state's western border (Fig. 1) lying principally within parallels 43 and 45 degrees north latitude and meridians, 103 and 104 degrees, 30 minutes, west longitude, largely in South Dakota, partly in Wyoming (Johnson 1949). Total area is about 5,150 mi2, including the Bear Lodge Mountains in northeastern Wyoming (Orr 1959). After leading a scientific party through the Black Hills in the summer of 1875, Colonel R. I. Dodge (1876) concluded: The Black Hills country is a true oasis in a wide and dreary desert. The approaches from every direction are through long 1 Approved by the director of the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station as Journal Series No. 1115. • Associate Professor of Range Ecology and Range Research Assistant, Animal Science Department, West River Agricultural Research and Extension Center of South Dakota State University, 801 San Francisco Street., Rapid City, South Dakota. 37 F. R. GARTNER AND W. ·W. THOMPSON o o o (Y) (\J o<::t o o MONTANA ---···----··~~------~------~--------L45° SOUTH DAKOTA ~ ______--4------- ____-+-44° WYOMING SCALE o••• miles 45 FIG. -

Deforestation and Forest Transition: Theory and Evidence in China

FOREST TRANSITION Deforestation and Forest Transition: Theory and Evidence in China by Yaoqi Zhang Abstract: A general theoretical framework on deforestation and forest transition is presented fol- lowed by empirical evidence from China. Relative scarcities of food, timber and environmental goods resulting from both population and economic growth are believed to be the most funda- mental causes of forest change. A relative scarcity of population a factor of production as well is considered to drive population change and re-allocation. The time required from deforestation to forest transition may be prolonged by the time lag in forest regeneration, and by the transaction costs, i.e. the costs in transferring, defining and protecting property rights of land and forests. The institutional issue is specially addressed throughout this article because the exclusion cost, i.e. the ex post cost of transaction in property rights of land and forests, is relatively large compared with other aspects of property protection. Consequently, active forest management is not econom- ically justified on a large part of land which otherwise should be under active management. This article concludes with a preliminary forecast of the future trend in Chinas forests and policy implications on future forest development. Keywords: Deforestation; forest transition; reforestation; transaction costs; economic reform; land use; population; China. 1 Introduction an increasing population for agricultural land and for timber are widely recognized While the forests in the developed coun- as the most important causes of deforesta- tries have ceased to shrink in area and have tion. However, the scarcity of timber, and even begun to expand a reversal which industrialization are generally viewed as 41 in this article is called forest transition accounting for forest transition (Rudel the developing countries are still in the de- 1998).